Approximately 55% of all mucosal melanomas (MMs) arise in the head and neck region. This disease represents less than 1% of all melanomas.1 MM is an aggressive neoplasm that exhibits unique features relative to other paranasal sinus and head and neck malignancies, as well as features distinct from cutaneous melanoma. Approximately two thirds of these lesions arise in the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, one quarter are found in the oral cavity, and the remainder occur sporadically in other mucosal sites of the head and neck.

MM is an aggressive neoplasm with staging introduced in the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual, 7th Edition for separate consideration from other mucosal-based lesions. The utility of this new system has been confirmed.2-5

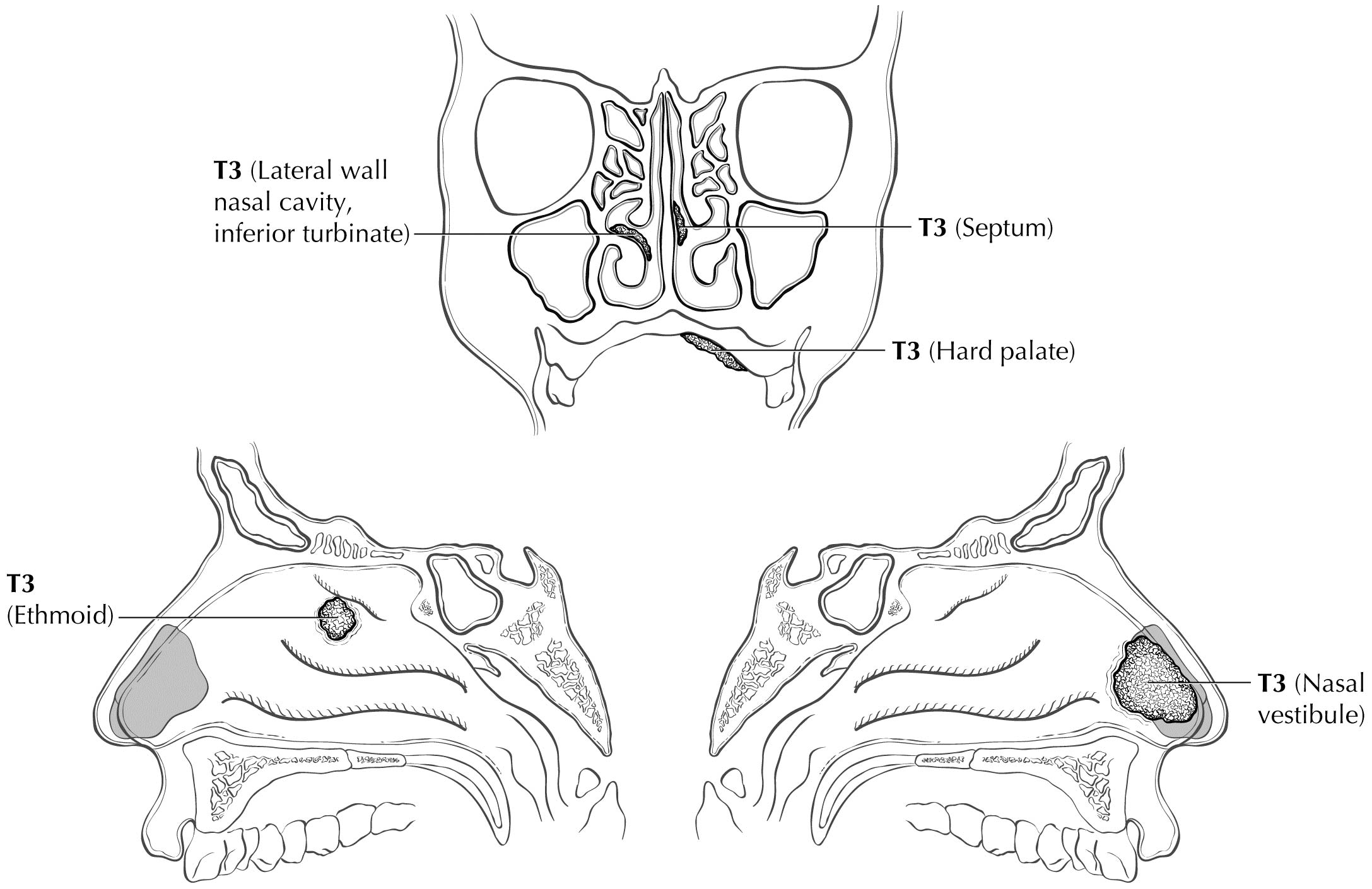

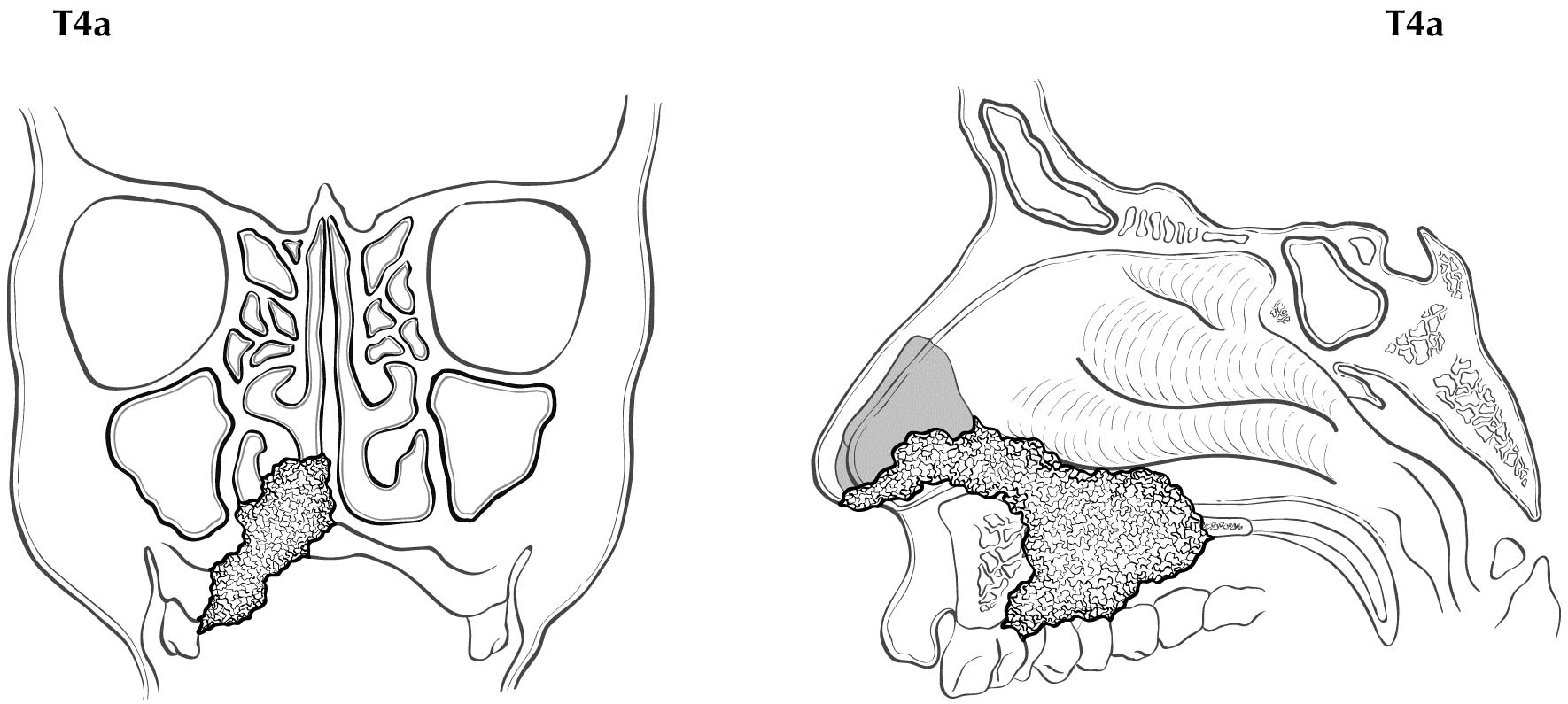

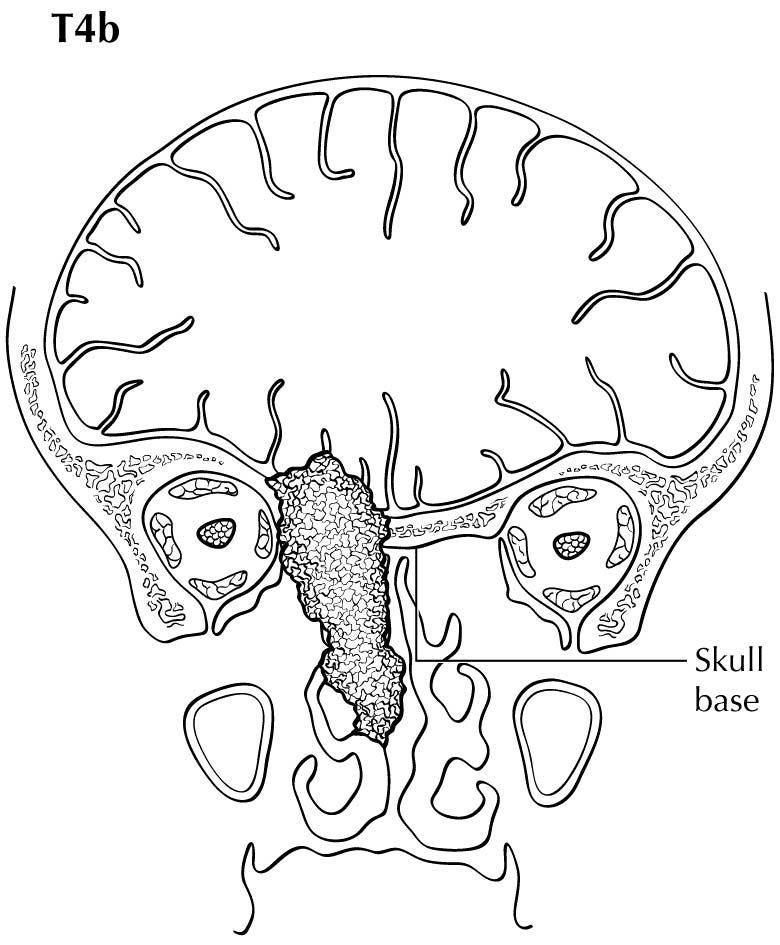

The staging system of Ballantyne showed its utility and emerged as the first staging system utilized specifically for MM.6 The TNM system for paranasal sinus cancer was not designed for and did not discriminate differences in prognosis between the various stages in MM. It also did not provide a staging system for MMs of the other potential sites where disease arose in the head and neck. Therefore, in the 7th Edition, AJCC and the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) adopted a novel system for MM using only T3, T4a, and T4b categories to characterize the local extent of disease. The lack of clear discrimination in outcomes based on the number and size of nodal metastases resulted in adopting a dichotomous categorization of N0 versus N+. Thus, the four stages of disease for MM are represented by III, IVA, IVB, and IVC. The system omits T1 and T2 categories, justified by the overall poor prognosis for even small superficial lesions. Stratification into these stages assists the clinician in treatment decision making. In Stage III disease, the role of radiation still is not completely certain, but should be strongly considered according to National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommendations; in Stage IVA, local radiation is important and confers a survival benefit.7

Stage IVB denotes extensive local invasion for which treatment often is a nonsurgical approach for local palliation. Stage IVC denotes distant metastatic disease.7 This stage designation allows patients to understand their prognosis. Furthermore, it provides a starting point for worldwide data collection and analysis. At this time, key genetic mutations such as BRAF are rarely seen in MM, thus making systemic treatment with targeted agents problematic.1

Prognostic Factors Required for Stage Grouping

Beyond the factors used to assign T, N, or M categories, no additional prognostic factors are required for stage grouping.

Additional Factors Recommended for Clinical Care

As with all cancers, the overall frailty and comorbidities of the patient are important determinants of prognosis. MM has few defined disease-specific prognostic factors. The site of origin in the head and neck is one of the only clear prognostic factors. Disease in the oral cavity has a higher rate of cervical nodal metastasis than those arising in the paranasal sinuses. Overall 5-year survival is 15-30% for nasal cavity, 12% for oral cavity, and 0-5% for paranasal sinus disease.9-11 Other series have demonstrated slightly better outcomes, but the relative proportion of survival remains best for nasal cavity and worst for paranasal sinus.

Prasad and colleagues proposed a microstaging system for MM. They reported that findings of vascular invasion, polymorphous tumor population, and necrosis conferred a worse prognosis.12 Others, however, have not confirmed these findings and suggest high mitotic index and other findings are more salient. At this time, it appears that no clear prognostic factors exist for MM, although many promising cand idates exist; collection of these data for future editions is advantageous.

In addition to the importance of the TNM factors, the overall health of these patients clearly influences outcome. An ongoing effort to better assess prognosis using both tumor and nontumor-related factors is underway. Chart abstraction will continue to be performed by cancer registrars to obtain important information regarding specific factors related to prognosis. These data then will be used to further hone the predictive power of the staging system in future revisions.

ComorbidityComorbidity can be classified by specific measures of additional medical illnesses. Accurate reporting of all illnesses in the patient's medical record is essential to assessment of these parameters. General performance measures are helpful in predicting survival. The AJCC strongly recommends the clinician report performance status using the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG),

Zubrod, or Karnofsky performance measures, along with stand ard staging information. An interrelationship between each of the major performance tools exists.

| Zubrod/ECOG Performance Scale | |

|---|

| 0 | Fully active, able to carry out all predisease activities without restriction (Karnofsky 90-100) |

| 1 | Restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to carry out work of a light or sedentary nature; for example, light housework, office work (Karnofsky 70-80) |

| 2 | Ambulatory and capable of all self-care, but unable to carry out any work activities; up and about more than 50% of waking hours (Karnofsky 50-60) |

| 3 | Capable of only limited self-care; confined to bed or chair 50% or more of waking hours (Karnofsky 30-40) |

| 4 | Completely disabled; cannot carry on self-care; totally confined to bed (Karnofsky 10-20) |

| 5 | Death (Karnofsky 0) |

Lifestyle FactorsLifestyle factors such as tobacco and alcohol abuse negatively influence survival. Accurate recording of smoking in pack-years and alcohol in number of days drinking per week and number of drinks per day will provide important data for future analysis. Nutrition is important to prognosis and will be indirectly measured by weight loss of greater than 5% of body weight in the previous 6 months.

14 Depression adversely affects quality of life and survival. Notation of a previous or current diagnosis of depression should be recorded in the medical record.

15 Tobacco UseThe role of tobacco as a negative prognostic factor is well established. Exactly how this could be codified in the staging system, however, is less clear. At this time, smoking is known to have a deleterious effect on prognosis but it is difficult to accurately apply this to the staging system. Smoking history should be collected as an important element of the demographics and may be included in Prognostic Groups in the future. For practicality, the minimum stand ard should classify smoking history as never, less than or equal to 10 pack-years, greater than 10 but less than or equal to 20 pack-years, or greater than 20 pack-years.

AJCC Level of Evidence: III Risk Assesment Models

The AJCC recently established guidelines that will be used to evaluate published statistical prediction models for the purpose of granting endorsement for clinical use.16 Although this is a monumental step toward the goal of precision medicine, this work was published only very recently. Therefore, the existing models that have been published or may be in clinical use have not yet been evaluated for this cancer site by the Precision Medicine Core of the AJCC. In the future, the statistical prediction models for this cancer site will be evaluated, and those that meet all AJCC criteria will be endorsed.

MM is a rare disease and difficult to address in clinical trials. Research should first focus on molecular signatures that predict outcome and response to therapy, presence of nodal disease, and multifocality. Additional features to be considered in stratification are vascular invasion, polymorphous tumor population, and necrosis.

Registry Data Collection Variables

- Size of lymph nodes

- Extracapsular extension from lymph node for head and neck

- Head and neck lymph nodes levels I-III

- Head and neck lymph nodes levels IV-V

- Head and neck lymph nodes levels VI-VII

- Other lymph node group

- Clinical location of cervical nodes

- ENE clinical

- ENE pathological

- Tumor thickness

Currently, there is no clear ability to determine prognosis based on histological differences.

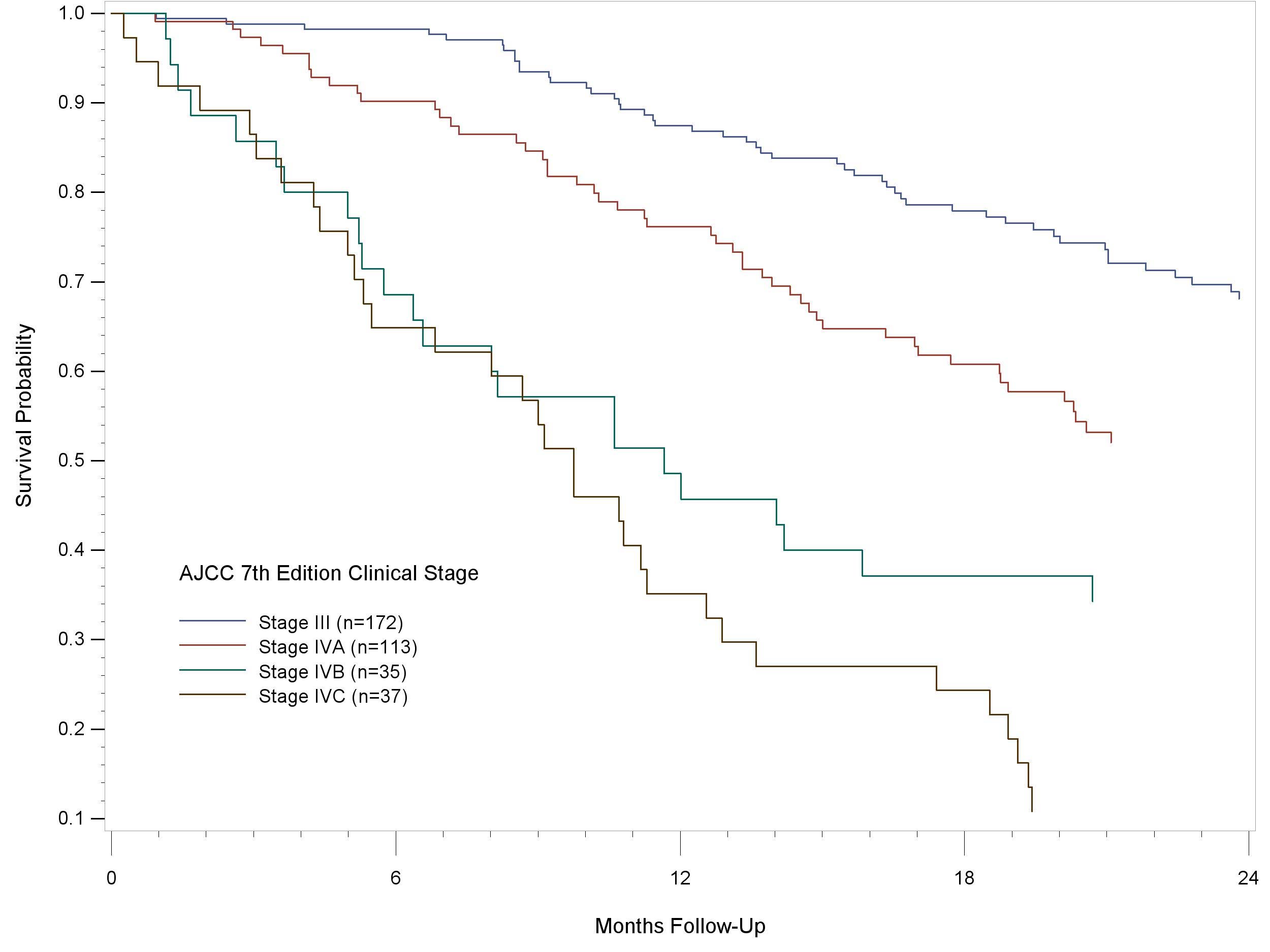

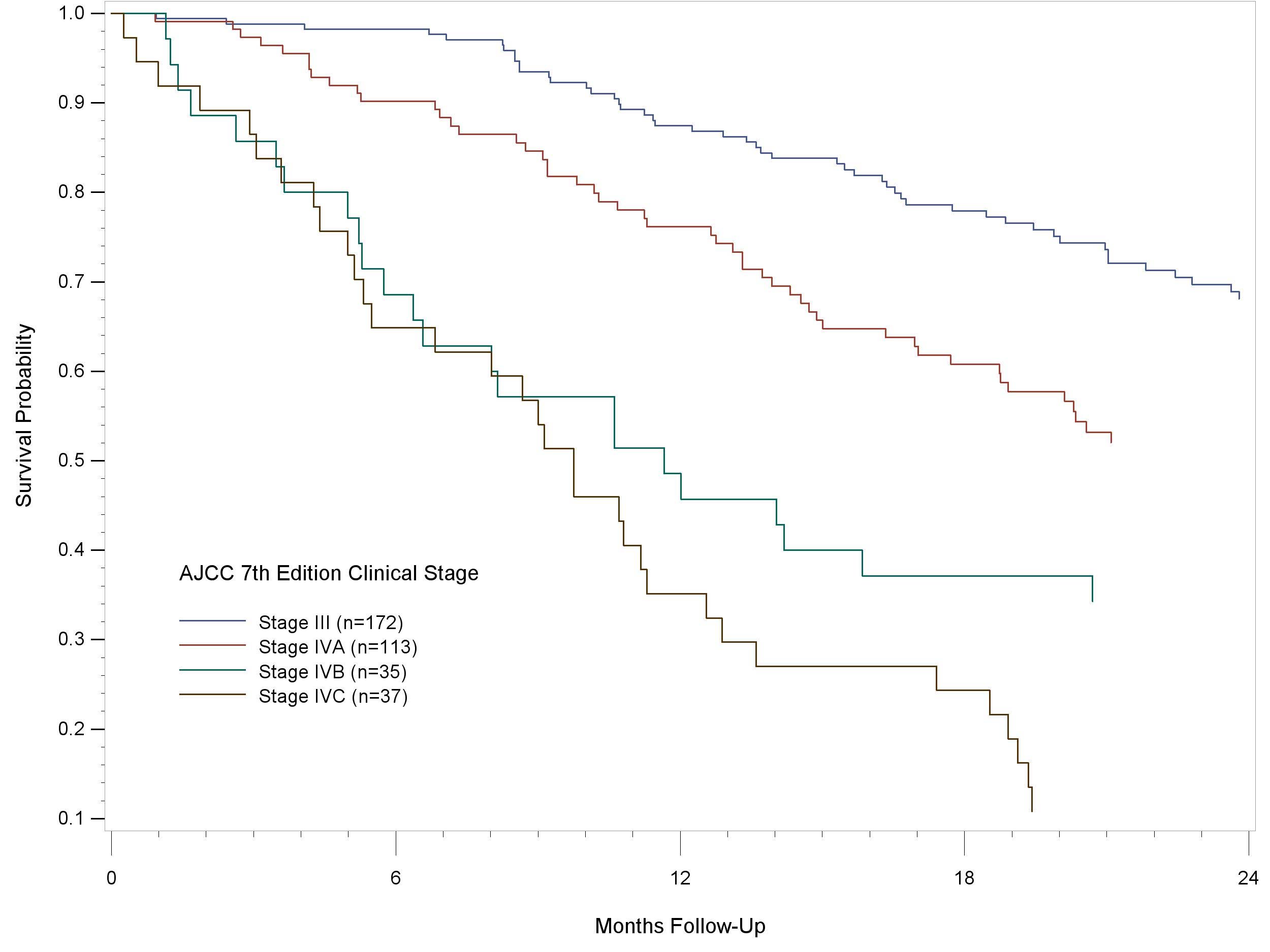

Figure 14.1 shows 24-month follow-up of patients older than 18 years of age, diagnosed with MM of the head and neck, lip and oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, and nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses using the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th Edition. The cases were diagnosed in 2010-12. The curves indicate a reasonable hazard discrimination and distribution. They also suggest good prognostic discrimination.

14.1 24-month follow-up of patients older than 18 years of age, diagnosed with MM of the head and neck, lip and oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, and nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses using the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th Edition. The cases were diagnosed in 2010-12.