Cancers Staged Using This Staging System

Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma or bile duct cancer, hilar cholangiocarcinoma, Klatskin tumor

Cancers Not Staged Using This Staging System

| These histopathologic types of cancer… | Are staged according to the classification for… | and can be found in chapter… |

|---|---|---|

| Sarcoma | Soft tissue sarcoma of the abdomen and thoracic visceral organs | 42 |

| Well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor (carcinoid) | No AJCC staging system | N/A |

Summary of Changes

| Change | Details of Change | Level of Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Definition of Primary Tumor (T) | The definition of Tis has been expand ed to include high-grade biliary intraepithelial neoplasia (BilIn-3). High-grade dysplasia (BilIn-3), a noninvasive neoplastic process, is synonymous with carcinoma in situ at this site. | N/A |

| Definition of Primary Tumor (T) | Bilateral second-order biliary radical invasion (Bismuth-Corlette type IV) has been removed from T4 category. | II |

| Definition of Regional Lymph Node (N) | N category was reclassified based on number of positive nodes to N1 (one to three positive nodes) and N2 (four or more positive nodes). | II |

| AJCC Prognostic Stage Groups | The stage group for T4 tumors was changed from Stage IVA to Stage IIIB. | II |

| AJCC Prognostic Stage Groups | N1 category was changed from Stage IIIB to IIIC, and N2 category is classified as Stage IVA. | II |

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| C24.0 | Proximal or perihilar bile ducts only |

This list includes histology codes and preferred terms from the WHO Classification of Tumors and the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O). Most of the terms in this list represent malignant behavior. For cancer reporting purposes, behavior codes /3 (denoting malignant neoplasms), /2 (denoting in situ neoplasms), and in some cases /1 (denoting neoplasms with uncertain and unknown behavior) may be appended to the 4-digit histology codes to create a complete morphology code.

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| 8010 | Carcinoma, NOS |

| 8010 | Carcinoma in situ , NOS |

| 8013 | Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) |

| 8020 | Undifferentiated carcinoma |

| 8041 | Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) |

| 8070 | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| 8140 | Adenocarcinoma |

| 8140 | Adenocarcinoma, biliary type |

| 8140 | Adenocarcinoma, gastric foveolar type |

| 8144 | Adenocarcinoma, intestinal type |

| 8148 | Biliary intraepithelial neoplasia, grade 3 (BilIn-3) |

| 8246 | Neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) |

| 8310 | Clear cell adenocarcinoma |

| 8470 | Mucinous cystic neoplasm with high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia |

| 8470 | Mucinous cystic neoplasm with an associated invasive carcinoma |

| 8480 | Mucinous adenocarcinoma |

| 8490 | Signet ring cell carcinoma |

| 8503 | Intraductal papillary neoplasm with high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia |

| 8503 | Intraductal papillary neoplasm with an associated invasive carcinoma |

| 8560 | Adenosquamous carcinoma |

Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon: IARC; 2010. Used with permission.

International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases for Oncology. ICD-O-3-Online.http://codes.iarc.fr/home. Accessed September 29, 2017. Used with permission.

Proximal or perihilar cholangiocarcinomas involve the main biliary confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts and comprise 50-70% of all cases of bile duct carcinomas. They are uncommon cancers, with an incidence of 1 to 2 per 100,000 in the United States. Complete resection with histopathologically negative margins is the most robust predictor of long-term survival. However, the apposition of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma to adjacent hepatic arterial and portal venous branches and hepatic parenchyma technically complicates complete resection.

Recent advances in dimensional imaging, perioperative care, and operative technique have increased rates of resectability. Specifically, the understand ing that perihilar cholangiocarcinoma extends proximally to involve intrahepatic bile ducts, with or without direct hepatic invasion and lobar hepatic atrophy, has led to routine incorporation of major hepatectomy, whether lobar, extended lobar, or total hepatectomy with transplantation, as an essential component of resection. These approaches have resulted in increased rates of margin-negative resection and improved overall survival.1-4

Before the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th Edition, perihilar and distal cholangiocarcinomas were grouped together as extrahepatic bile duct cancer. The prognostic accuracy of the separate perihilar cholangiocarcinoma TNM staging was validated independently.5

Cholangiocarcinoma develops anywhere within the biliary tree and arises from the most proximal intrahepatic bile ducts to the most distal intraduodenal bile duct. Extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma was separated traditionally into perihilar, mid-duct, and distal cholangiocarcinoma. However, mid-duct cholangiocarcinomas do not comprise a separate site for staging. The AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th Edition, affirms the prior stratification of cholangiocarcinoma into proximal and distal cholangiocarcinoma.

Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma is defined as arising predominantly in the main lobar extrahepatic bile ducts distal to segmental bile ducts and proximal to the cystic duct. Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma is characterized predominantly by local and regional growth patterns. Perineural invasion is typical for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma, and spread through periductal lymphatic channels is common. Cholangiocarcinoma may extend intrahepatically or proximally with involvement of the lobar sectoral and segmental bile ducts. Cholangiocarcinoma may extend radially with involvement of the hepatic parenchyma and hepatic arterial or portal venous vasculature, or both.

Hilar, cystic duct, choledochal, portal, hepatic arterial, and posterior pancreaticoduodenal lymph nodes are classified as regional lymph nodes.

Most patients diagnosed with perihilar cholangiocarcinoma are older than 60 years, with peak incidence in the eighth decade of life.6 Risk factors for developing perihilar cholangiocarcinoma include hepatolithiasis, biliary parasites, and choledochal cysts. In the United States, the most common identifiable risk factor is primary sclerosing cholangitis, an autoimmune disease that predisposes the entire biliary tree to the development of malignancy. Most cases of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma are sporadic, without identifiable risk factors.

Early symptoms are nonspecific and include constitutional symptoms of abdominal discomfort, anorexia, and weight loss. Symptoms and signs from bile duct obstruction, with jaundice, acholic stools, dark urine, and pruritus, occur frequently, regardless of disease stage.7 Diagnosis of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma may be challenging, with frequent indeterminate or false negative results from bile duct biopsies and biliary brushing cytology. Elevated serum cancer antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) levels greater than 100 U/mL lend support to the diagnosis.8 Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis increases the sensitivity of cytology in diagnosing perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. In a patient with a resectable, malignant-appearing stricture involving the proximal biliary tree, pathological diagnosis of cancer is not compulsory before surgical exploration.

Most patients with perihilar cholangiocarcinoma have locoregional extension or distant metastasis that precludes resection and thus are treated, and do not qualify for pathological staging. A single TNM classification must apply to both clinical and pathological staging. Therefore, in most patients with perihilar cholangiocarcinoma, the basis for TNM staging is high-quality cross-sectional imaging. Peritoneal metastases may be radiographically occult and in patients undergoing surgery, identified only at time of staging laparoscopy.

The 7th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual reclassified adjacent hepatic parenchymal invasion as T2 but maintained unilateral vascular involvement as T3. The current edition affirms findings supporting that classification.9

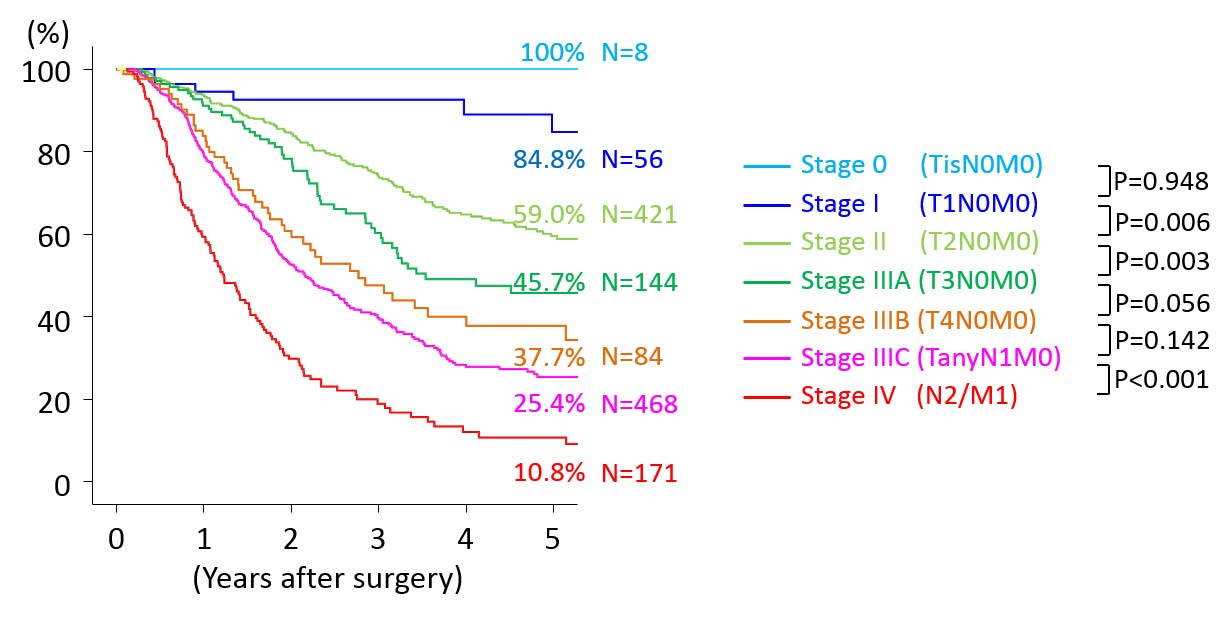

The 7th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual defined T4 cholangiocarcinoma as cholangiocarcinoma with bilateral involvement of hepatic arterial or portal vasculature, bilateral ductal extension into the secondary or segmental bile ducts (Bismuth-Corlette type IV), and ductal extension into the secondary or segmental bile ducts with contralateral involvement of the hepatic vasculature. The current edition of AJCC Cancer Staging Manual eliminates bilateral ductal extension into the secondary or segmental bile ducts (Bismuth-Corlette type IV) alone from T4 cholangiocarcinoma. Thus, the current T category definitions exclude any Bismuth-Corlette typing. Such tumors were previously classified as Stage IVA disease and now are distributed by other T and N criteria into overall disease stage. The modified T categories have resulted in improved stratification of overall survival (Figure 25.1).10

Lobar hepatic atrophy of variable extent is often associated with perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Atrophy typically is associated with an advanced T category and ipsilateral portal venous obstruction. Because hepatic atrophy in advanced degrees reduces resectability, it has been proposed as a group component.4 However, because the spectrum of hepatic atrophy is based on radiographic and gross clinical findings and not by histopathological criteria, atrophy is not incorporated into the current staging system.

Imaging

Clinical evaluation usually depends on the results of duplex ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). Patients typically present with jaundice and undergo ultrasound as their first imaging modality. High-quality multidetector CT should demonstrate the level of biliary obstruction, vascular involvement, liver atrophy, and presence of nodal and distant metastases. The biliary extent of disease is assessed with percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography or MRCP. CT and /or MRCP should be performed before placement of biliary stents, which can obscure anatomic detail.

Cross-sectional imaging can also demonstrate the presence of lobar atrophy, which indicates the presence of biliary and /or vascular involvement and represents a gross and significant reduction of expected stand ard liver volume of the involved liver. Lobar atrophy is an important consideration before surgery, since an inadequate liver remnant volume can preclude hepatic resection or require preoperative portal vein embolization to induce hypertrophy of the remnant liver.

Clinical staging also may be based on findings from surgical exploration when the main tumor mass is not resected.

Suggested Report FormatMacroscopically, perihilar cholangiocarcinoma is classified into three subtypes: papillary, nodular, and sclerosing.14 Sclerosing cholangiocarcinoma, the most frequent subtype, is characterized by periductal infiltration and desmoplasia. The nodular subtype is characterized by local irregular infiltration into the bile duct. Often, features of both nodular and sclerosing subtypes are observed together. Papillary tumors account for 5-10% of cases and frequently are soft and friable, with limited mural invasion. Papillary cholangiocarcinoma is more often surgically resectable and has a better prognosis than nodular and sclerosing subtypes.

Tumors classified as Tis cytologically resemble carcinoma, with diffuse, severe distortion of cellular polarity, but invasion through the basement membrane is absent.15

Complete resection of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma requires en bloc resection of the liver (usually major anatomic hepatectomy), extrahepatic bile duct, and hepatoduodenal lymph nodes. If involved, the portal vein and /or hepatic artery may need resection and reconstruction. The extent of resection (R0, complete resection with grossly and microscopically negative margins of resection; R1, grossly negative but microscopically positive margins of resection; R2, grossly and microscopically positive margins of resection) is a descriptor in the TNM staging system, is the most important stage-independent prognostic factor, and should be reported.

Patients who undergo surgical resection for localized perihilar cholangiocarcinoma have a median survival of approximately 3 years and a 5-year survival rate of 20-40%. In carefully selected patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and locally unresectable lymph node-negative perihilar cholangiocarcinoma, excellent survival has been reported after neoadjuvant chemoradiation and liver transplantation.

Extended hepatic resections (trisectorectomy) with resection and reconstruction of the hepatic remnant portal vein and hepatic artery have been used increasingly, with promising early outcomes. Complete resection with negative histopathologic margins is the major predictor of outcome. Invasive, but not in situ, carcinoma at the margin of resection adversely affects survival. Hepatic resection is considered integral to achieving negative proximal intrahepatic margins. Factors adversely associated with survival include high tumor grade, vascular invasion, and lymph node metastasis.

The prevalence of lymphatic metastases increases directly with T categories and ranges overall from 30-53% by site. Nodal involvement adversely correlates with survival.16 Accurate localization of the site of lymph nodes in the hepatoduodenal ligament is difficult. Because the total number of metastatically involved lymph nodes correlates with survival, the number of positive lymph nodes has been added to classify N categories. Regional lymph node involvement is stratified into three N groupings: N0 (no lymph node involvement), N1 (one to three positive lymph nodes), and N2 (four or more positive lymph nodes).

Prognostic Factors Required for Stage Grouping

Beyond the factors used to assign T, N, or M categories, no additional prognostic factors are required for stage grouping.

Additional Factors Recommended for Clinical Care

The Bismuth-Corlette classification describes the location and extent of biliary infiltration by tumor. Bismuth-Corlette type IV tumors, defined as tumor invasion of second-order biliary radicals bilaterally, are associated with a higher rate of positive surgical margins and significantly poorer 5-year overall survival after resection than Bismuth-Corlette types I to III.10

| Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| I | Tumor is limited to the common hepatic duct, below the level of the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts |

| II | Tumor involves the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts |

| IIIa | Tumor with type II involvement plus extension to the right 2nd-order ducts |

| IIIb | Tumor with type II involvement plus extension to the left 2nd-order ducts |

| IV | Tumor extends into both right and left 2nd-order ducts |

Papillary tumors account for approximately one quarter of hilar cholangiocarcinomas in surgical series. They are characterized by an intraductal growth pattern, are more often well-differentiated, and confer a higher median disease-specific survival after resection: 58 months, compared with 36 months for nonpapillary tumors (p = 0.01).4

Primary sclerosing cholangitis is an idiopathic chronic liver disease characterized by inflammation and fibrosis of the entire biliary tree. The chronic inflammation and injury to ducts may lead to cirrhosis and predispose to cholangiocarcinomas at any site in the biliary tree. Patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis are advised to receive neoadjuvant chemoradiation and liver transplantation.14

The authors have not noted any emerging factors for clinical care.

The AJCC recently established guidelines that will be used to evaluate published statistical prediction models for the purpose of granting endorsement for clinical use.17 Although this is a monumental step toward the goal of precision medicine, this work was published only very recently. Therefore, the existing models that have been published or may be in clinical use have not yet been evaluated for this cancer site by the Precision Medicine Core of the AJCC. In the future, the statistical prediction models for this cancer site will be evaluated, and those that meet all AJCC criteria will be endorsed.

Definition of Primary Tumor (T)

| T Category | T Criteria |

|---|---|

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ/high-grade dysplasia |

| T1 | Tumor confined to the bile duct, with extension up to the muscle layer or fibrous tissue |

| T2 | Tumor invades beyond the wall of the bile duct to surrounding adipose tissue, or tumor invades adjacent hepatic parenchyma |

| T2a | Tumor invades beyond the wall of the bile duct to surrounding adipose tissue |

| T2b | Tumor invades adjacent hepatic parenchyma |

| T3 | Tumor invades unilateral branches of the portal vein or hepatic artery |

| T4 | Tumor invades the main portal vein or its branches bilaterally, or the common hepatic artery; or unilateral second-order biliary radicals with contralateral portal vein or hepatic artery involvement |

Definition of Regional Lymph Node (N)

| N Category | N Criteria |

|---|---|

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | One to three positive lymph nodes typically involving the hilar, cystic duct, common bile duct, hepatic artery, posterior pancreatoduodenal, and portal vein lymph nodes |

| N2 | Four or more positive lymph nodes from the sites described for N1 |

Definition of Distant Metastasis (M)

| M Category | M Criteria |

|---|---|

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasis |

Registry Data Collection Variables

Adenocarcinoma that is not further subclassified is the most common histologic type.

| G | G Definition |

|---|---|

| GX | Grade cannot be assessed |

| G1 | Well differentiated |

| G2 | Moderately differentiated |

| G3 | Poorly differentiated |