Primary Site(s)

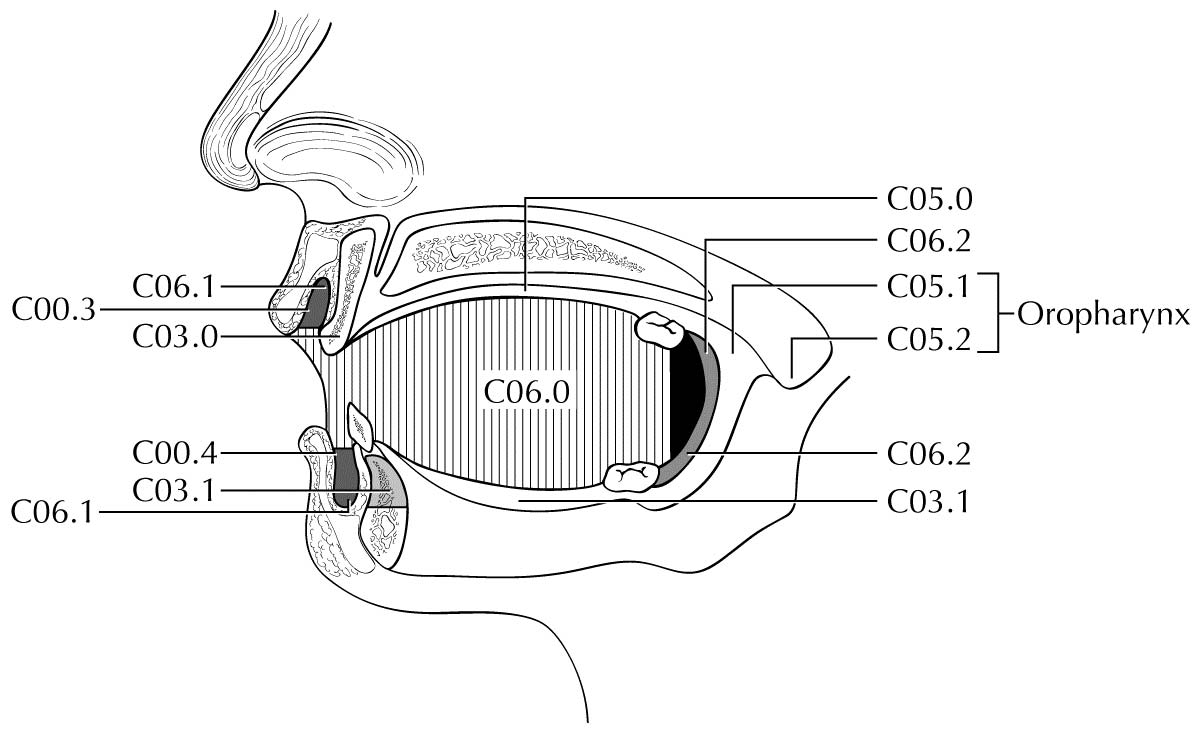

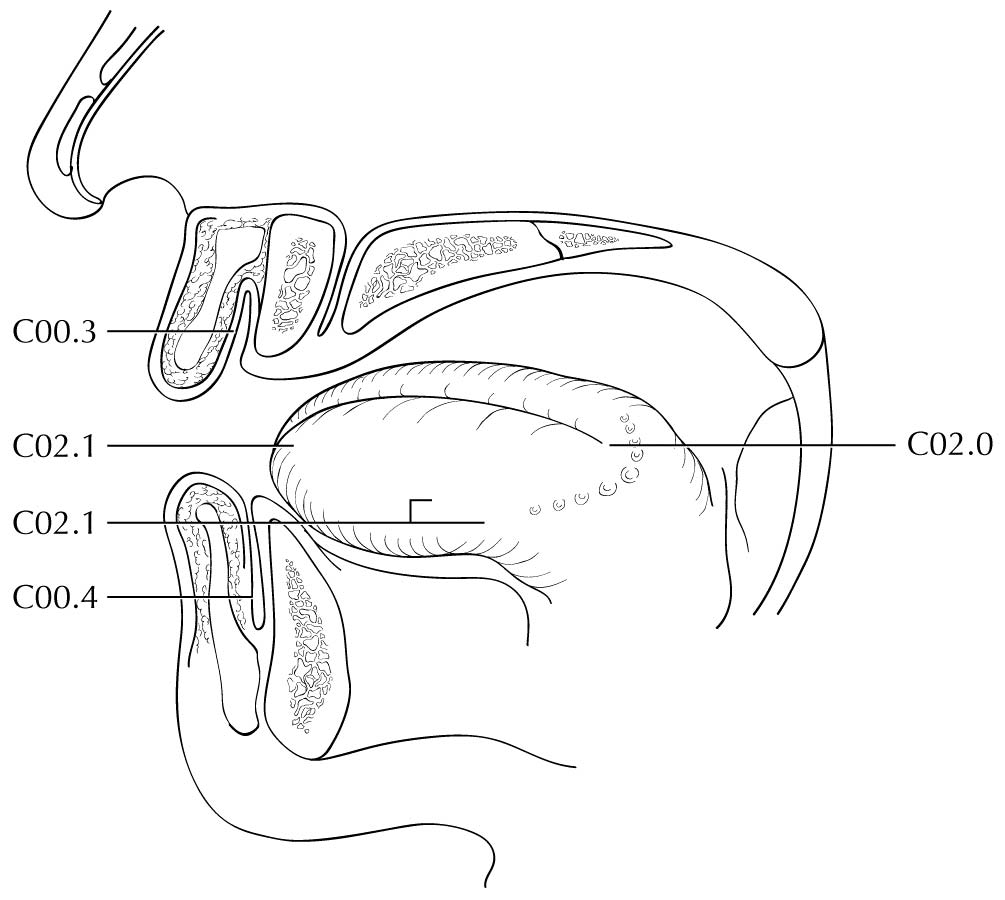

The oral cavity extends from the portion of the lip that contacts the opposed lip (wet mucosa) to the junction of the hard and soft palate above, to the line of circumvallate papillae below, and to the anterior tonsillar pillars laterally. It is additionally divided into multiple specific sites described in this section.

Mucosal Lip

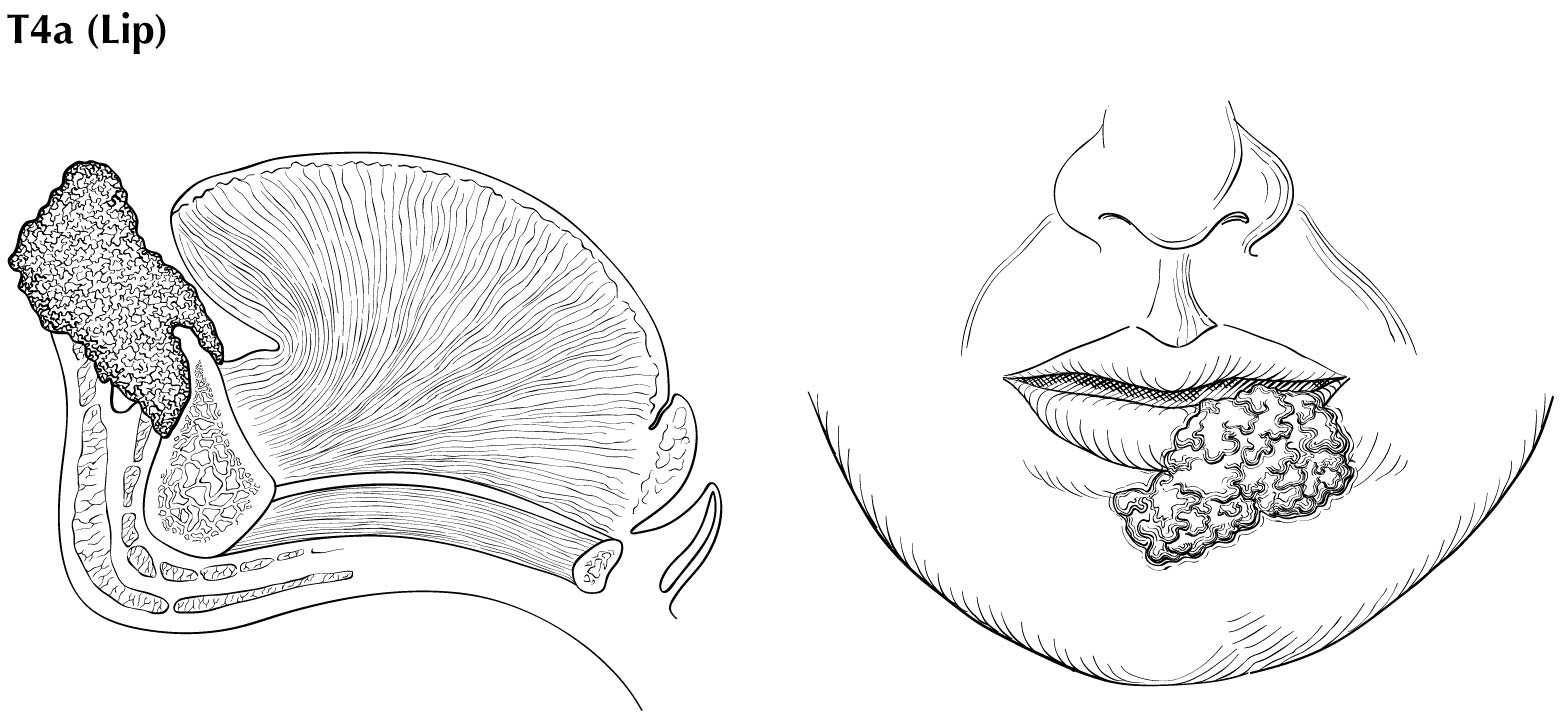

The mucosal lip begins at the junction of the wet and dry mucosa of the lip (the anterior border of the portion of the lip that comes into contact with the opposed lip) and extends posteriorly into the oral cavity to the attached gingiva of the alveolar ridge. The dry vermilion lip and vermilion border is staged using the chapter on cutaneous carcinoma of the head and neck (Chapter 15). This is a change from past AJCC editions where the dry vermilion was included in the lip and oral cavity chapter.

Buccal Mucosa

The buccal mucosa includes all the mucous membrane lining of the inner surface of the cheeks and lips from the line of contact of the opposing lips to the line of attachment of mucosa of the alveolar ridge (upper and lower) and pterygomandibular raphe.

Lower Alveolar Ridge

The lower alveolar ridge refers to the mucosa overlying the alveolar process of the mandible, which extends from the line of attachment of mucosa in the lower gingivobuccal sulcus to the line of attachment of free mucosa of the floor of the mouth. Posteriorly, it extends to the ascending ramus of the mandible.

Upper Alveolar Ridge

The upper alveolar ridge refers to the mucosa overlying the alveolar process of the maxilla, which extends from the line of attachment of mucosa in the upper gingivobuccal sulcus to the junction of the hard palate. Its posterior margin is the upper end of the pterygopalatine arch.

Retromolar Gingiva (Retromolar Trigone)

The retromolar gingiva, or retromolar trigone, is the attached mucosa overlying the ascending ramus of the mandible from the level of the posterior surface of the last lower molar tooth to the apex superiorly, adjacent to the tuberosity of the maxilla.

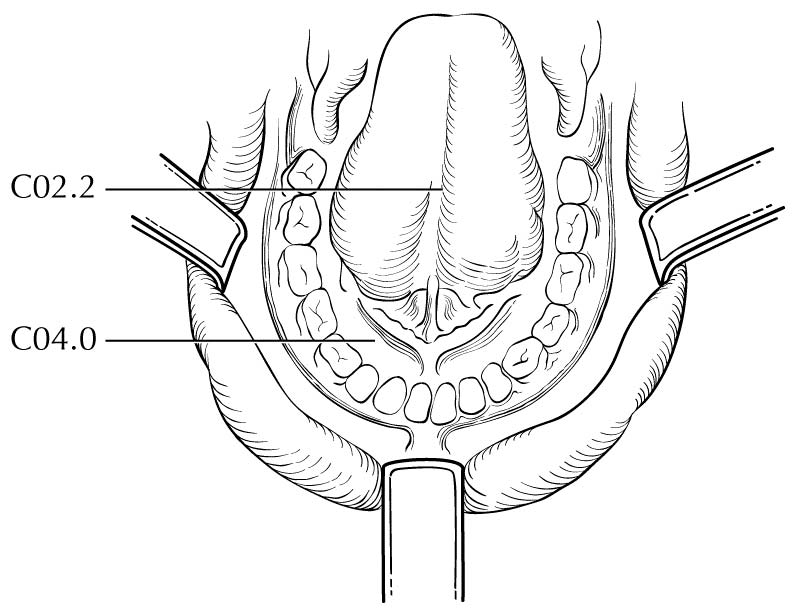

Floor of the Mouth

The floor of the mouth is a crescentic surface overlying the mylohyoid and hyoglossus muscles, extending from the inner surface of the lower alveolar ridge to the undersurface of the tongue. Its posterior boundary is the base of the anterior pillar of the tonsil. It is divided into two sides by the frenulum of the tongue and harbors the ostia of the submandibular and sublingual salivary glands.

Hard Palate

The hard palate is the semilunar area between the upper alveolar ridge and the mucous membrane covering the palatine process of the maxillary palatine bones. It extends from the inner surface of the superior alveolar ridge to the posterior edge of the palatine bone.

Anterior Two-Thirds of the Tongue (Oral Tongue)

The anterior two-thirds of the tongue is the freely mobile portion of the tongue that extends anteriorly from the line of circumvallate papillae to the undersurface of the tongue at the junction with the floor of the mouth. It is composed of four areas: the tip, the lateral borders, the dorsum, and the undersurface (nonvillous ventral surface of the tongue). The undersurface of the tongue is considered a separate category by the World Health Organization (WHO).

Regional Lymph Nodes

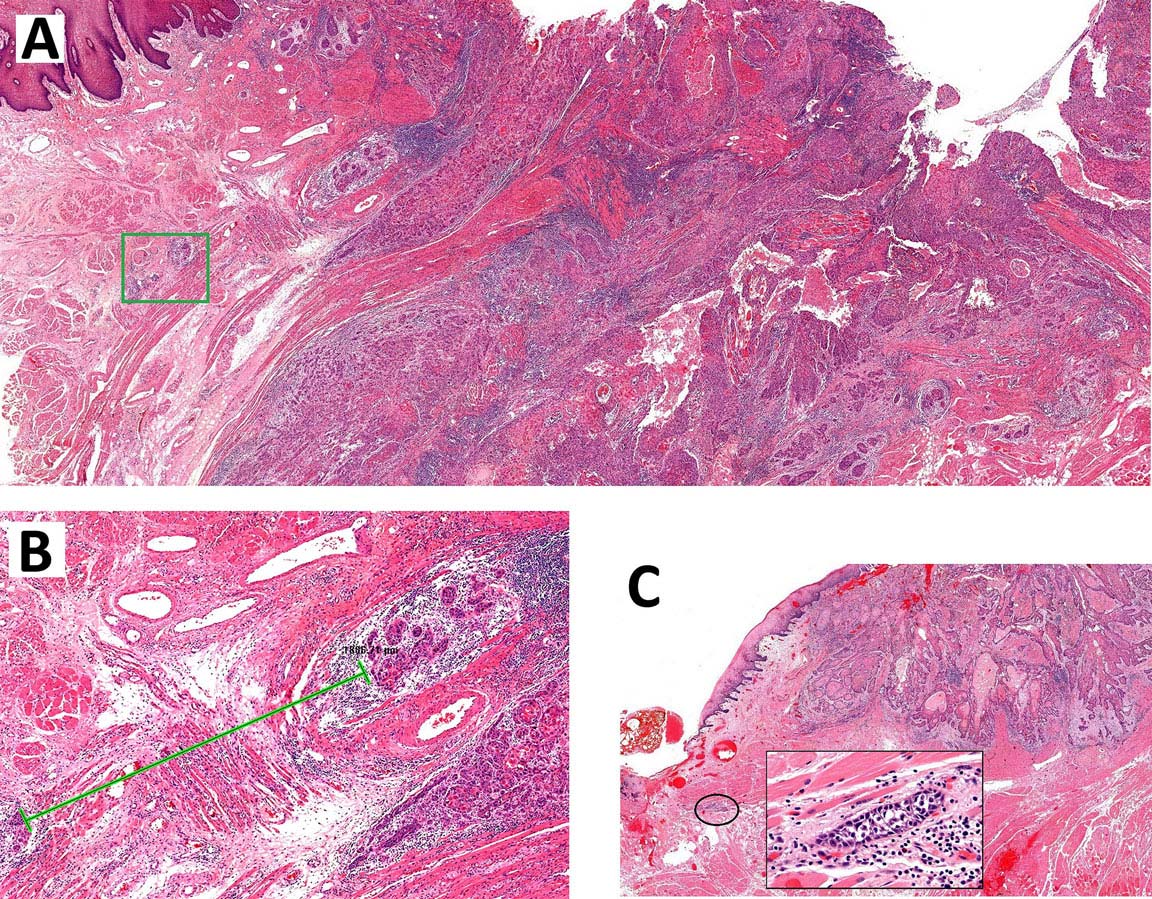

The risk of regional metastasis is generally related to the T category as well as worst tumor pattern of invasion (WPOI). Cervical metastases are uncommon among tumors with nonaggressive WPOI (types 1, 2, 3) with increasing likelihood of metastasis for WPOI-4 and WPOI-5. In general, cervical lymph node involvement from oral cavity primary sites is predictable and orderly, spreading from the primary to upper, then middle, and subsequently lower cervical nodes. Any previous treatment of the neck, through surgery or radiation, may alter normal lymphatic drainage patterns and result in unusual dissemination of disease to the cervical lymph nodes. Cancer of the mucosal lip, with a low metastatic risk, initially involves adjacent submental and submandibular nodes, then jugular nodes. Cancers of the hard palate likewise have a low metastatic potential and involve buccinator, pre-vascular facial and submandibular, jugular, and, occasionally, retropharyngeal nodes. Other oral cancers spread primarily to submandibular and jugular nodes and uncommonly to posterior triangle/supraclavicular nodes. Cancer of the anterior oral tongue may occasionally spread directly to lower jugular nodes. The closer the primary is to the midline, the greater the propensity for bilateral cervical nodal spread. Although patterns of regional lymph node metastases are typically predictable and sequential, disease in the anterior oral cavity also may spread directly to bilateral or mid-cervical lymph nodes.

Clinical Classification

Clinical staging for Oral Cavity cancers is predicated most strongly upon the history and physical examination. Biopsy is necessary to confirm diagnosis and is typically performed on the primary. Nodal biopsy is done by fine needle aspiration when indicated. Results from diagnostic biopsy of the primary tumor, regional nodes, and distant metastases can be included in clinical classification.

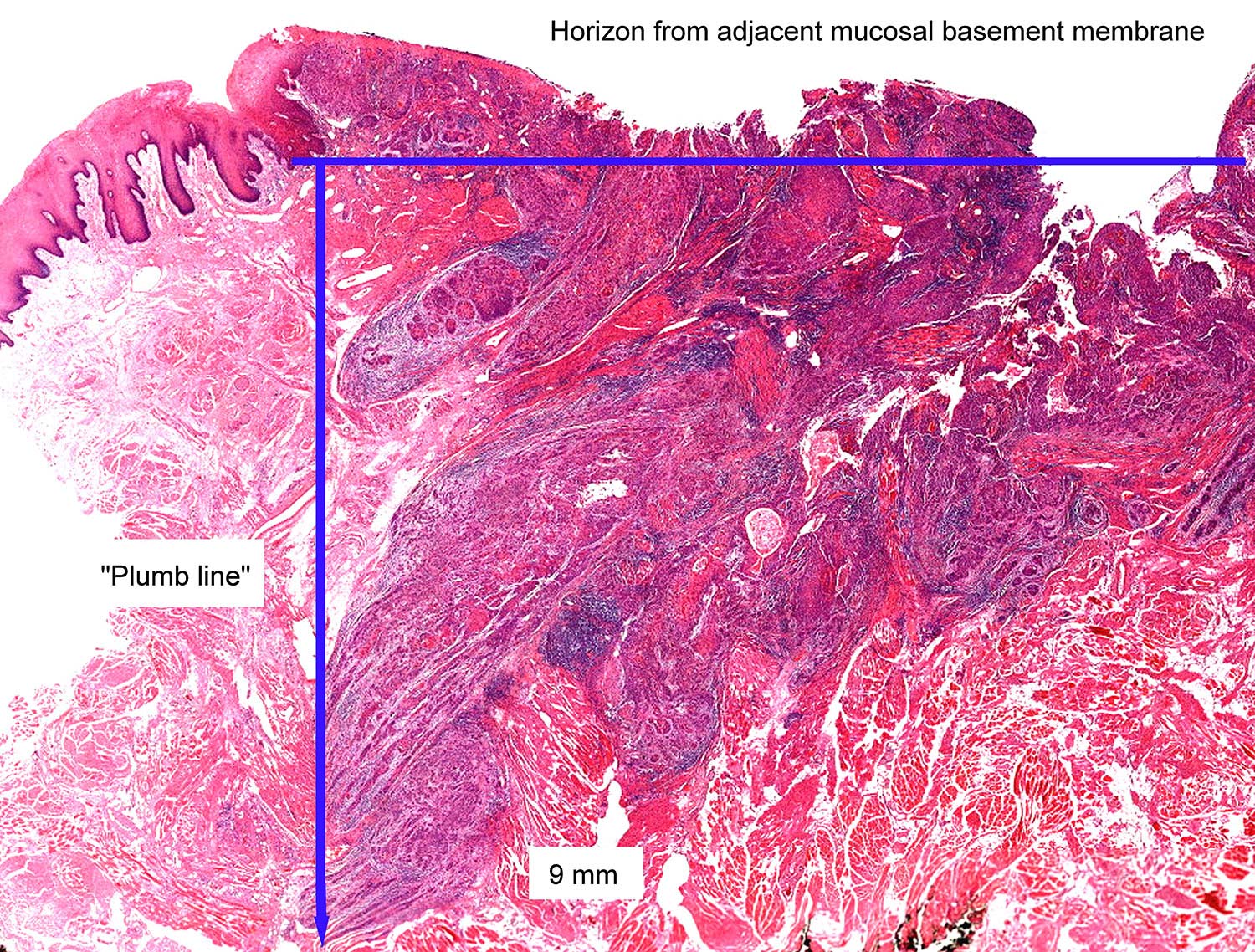

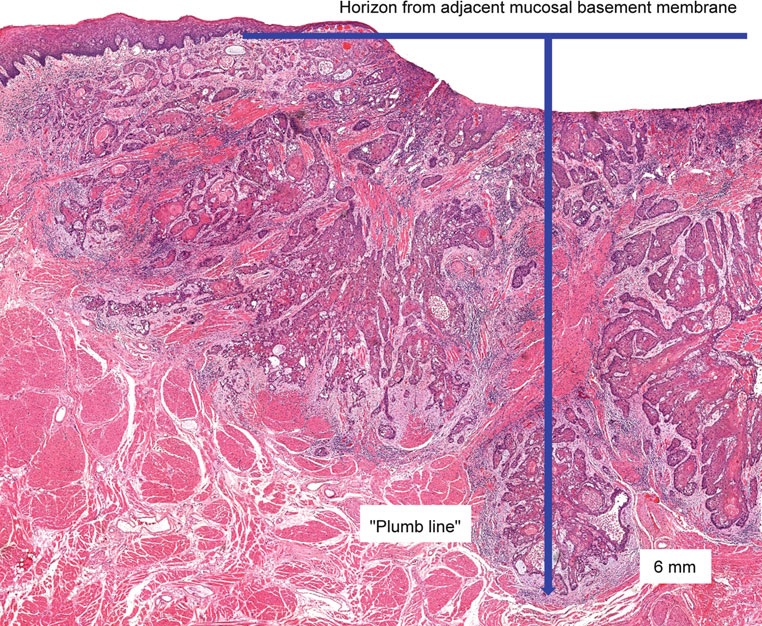

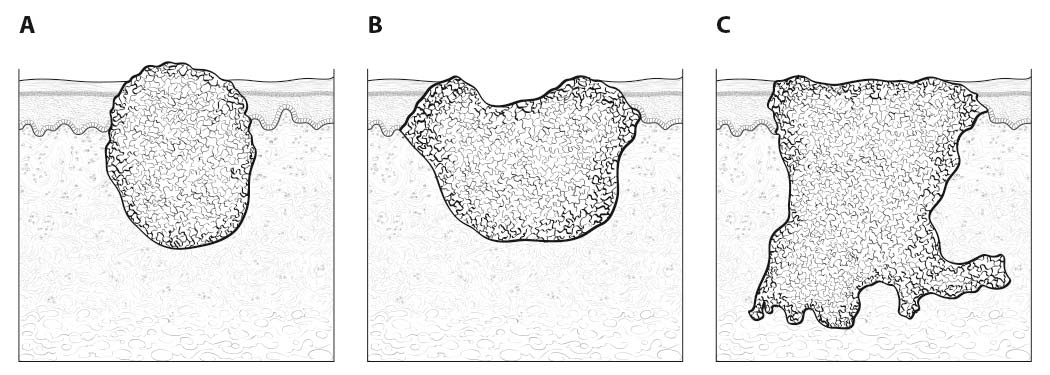

Inspection of the oral cavity typically reveals the greatest diameter of a cancer, though palpation is essential to assess DOI and submucosal extension. The mucosal extent of the cancer usually reflects its true linear dimension. Induration surrounding a cancer typically is due to peritumoral inflammation. DOI should be distinguished from tumor thickness, and its determination is predicated on invasion beneath the plane defined by surrounding normal mucosa. Any exophytic character should be noted, but assignment of stage is determined by what transpires at or beneath the surface (defined by adjacent normal mucosa). Clinical evidence of bone destruction should be noted and its depth estimated (e.g., into bone versus through cortex into the marrow space). Thick lesions often are defined by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, but the difference between thickness and DOI must be observed. Lesions located near the midline more often involve the contralateral side of the neck than well-lateralized cancers. Dysphagia is suggestive of a tumor with sufficient invasion of oral structures to engender dysfunction. It is seldom present when cancers have little DOI. Similarly, drooling or the inability to swallow liquids without difficulty suggests a tumor with substantial DOI. Trismus, when not caused by pain, is consistent with a deeply invasive lesion. Complaints of numbness of the lip and/or teeth are commonly associated with nerve invasion. Clinicians experienced with head and neck cancer will generally have few problems distinguishing less invasive lesions (≤ 5 mm) from those of moderate depth (from > 5 to ≤ 10 mm) or deeply invasive cancers (> 10 mm) through examination alone. Such experts have estimated the maximum dimensions for complicated lesions of the tonsil or palate for many years. However, the distinction between 4 mm DOI and 6 mm DOI (for example) may not be possible on clinical grounds. A higher T category should be assigned on the basis of DOI only if the differences in DOI are clear.

Evidence of cranial nerve dysfunction should be sought (testing sensation and motion to command) and skin should be examined for evidence of invasion by underlying nodes. Palpable neck nodes should be considered in terms of their location (level in the neck), size, number, character (smooth or irregular), attachment to other nodes, and mobility. Nodes that do not move in all directions may be invading nearby structures. Invasion of the sternomastoid muscle and/or cranial nerves is associated with lateral motion with restricted ability to move the node along the cranial-caudal axis. Inability to move the node at all (without moving the head) is worrisome for ENE, though the suspicion should be tempered for smaller nodes with limited mobility in level II. Assignment of clinical ENE should be based almost entirely upon the physical examination, rather than upon imaging studies; gross ENE is required to raise the cN category beyond the assignment based upon node size and number, and this may be overestimated with current imaging modalities.

Clinical or radiographic extranodal extension

ENE worsens the adverse outcome associated with nodal metastasis. The presence of ENE can be diagnosed clinically by the presence of a “matted” mass of nodes, involvement of overlying skin, adjacent soft tissue, or clinical signs of cranial nerve or brachial plexus, sympathetic chain or phrenic nerve invasion. Cross-sectional imaging (CT or MR) generally has low sensitivity (65-80%) but high specificity (86-93%) for the detection of ENE. The most reliable imaging signs are an indistinct nodal margin, irregular nodal capsular enhancement or infiltration into the adjacent fat or muscle, with the latter finding on CT and MR imaging as the most specific sign of ENE. Ultrasound appears to be less accurate than CT and MR imaging, but ENE is suggested by interrupted or undefined nodal contours with high-resolution ultrasound imaging. The absence or presence of clinical/radiologic ENE is designated ENE(-) or ENE(+), respectively.

Imaging

Cross-sectional imaging of the oral cavity may be performed with either CT or MR imaging, depending on availability, patient imaging tolerance, contrast allergies, and cost. With either modality, the coronal plane view—either as direct MR imaging or from reformats obtained from axially acquired thin-slice CT—allows excellent evaluation of the floor of the mouth.9 CT offers some advantage over MR imaging in the evaluation of cortical bone erosion, although MR imaging appears to be more sensitive but less specific for the detection of bone marrow invasion by tumor.10,11 MR imaging offers the additional advantage of evaluation of perineural tumor spread, which for oral cavity tumors is primarily along the inferior alveolar nerve (CNV3) of the mandible and the greater and lesser palatine nerves (CNV2) of the maxilla. Gadolinium contrast is always recommended unless contraindicated by prior reaction or very poor renal function. Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT is primarily done for nodal staging of disease or when distant metastases are suspected, unless the CT component is performed as a post-contrast examination with dedicated neck imaging. Ultrasound does not allow adequate evaluation of the oral cavity primary tumor site, but it may be a useful adjunct for estimating DOI and for nodal evaluation with otherwise equivocal nodal imaging findings.

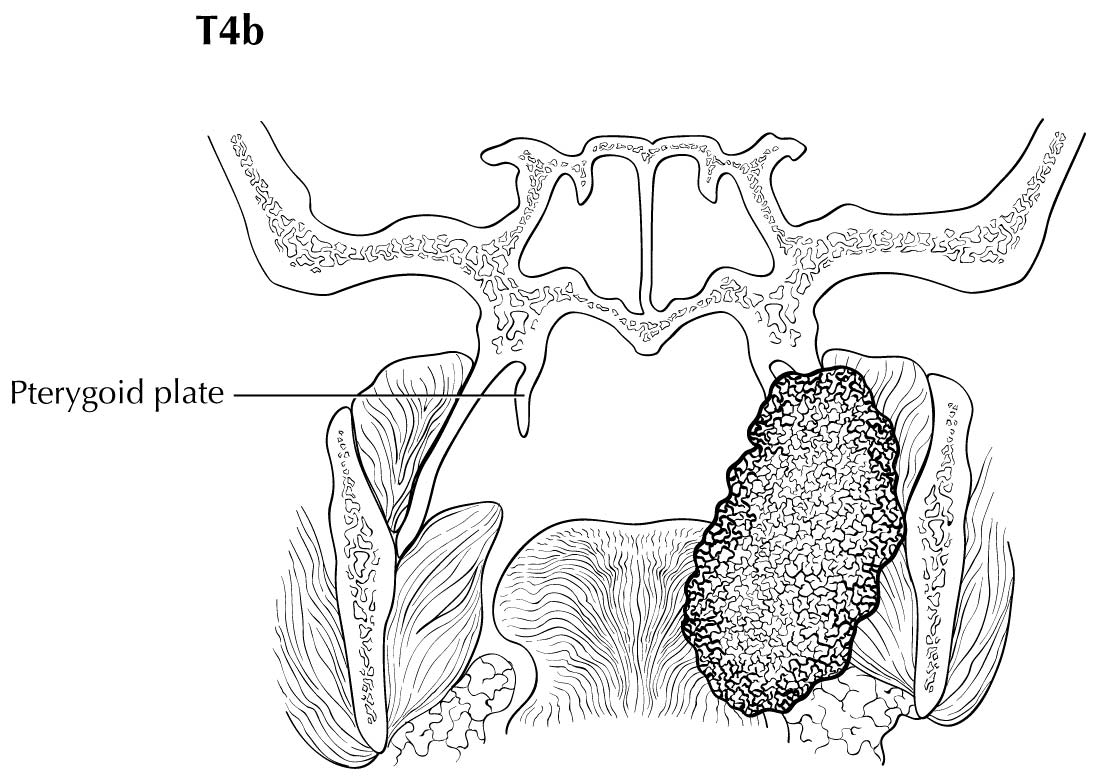

As small but clinically evident mucosal tumors may be subtle on imaging, it is important to review the imaging exam with knowledge of the tumor site. T1, T2, and T3 tumors are distinguished only by size and depth of invasion. The former is better determined by clinical examination, although a radiologic measurement should be given as part of the imaging report. The radiologist's more important role during tumor staging is to determine deep tissue involvement and assess for nodal and/or distant metastases. T4 disease entails invasion into adjacent bone, sinus or skin, or else large transverse size (> 4 cm) and greater than 10 mm, which varies according to the specific subsite of the oral cavity. For alveolar ridge, floor of mouth, retromolar triangle, hard palate, and large lip tumors, careful attention should be paid to the cortex and marrow space of the adjacent maxilla or mandible, because such invasion denotes T4a disease. In the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th Edition, oral tongue tumors were designated T4a when there was deep invasion into the extrinsic muscles of the tongue and/or the floor of the mouth. DOI supersedes muscle invasion in the 8th Edition. Depth is frequently better evaluated in the coronal plane and/or sagittal plane. More posterior extensive spread of tumor—such as buccal tumors invading into the muscles of mastication, or spreading to the pterygoid plates or superiorly to the skull base—denotes T4b tumor. Additionally, posterolateral tumor spread to surround the internal carotid artery is also T4b disease.

Both CT and MR imaging allow evaluation of nodal morphology to determine possible tumor involvement. Levels IA, IB, and IIA are the most frequently involved sites, and these levels should be scrutinized specifically with concern for rounded contour, heterogeneous texture including cystic or necrotic change, enlargement, and ill-defined margins. It also is important to be cognizant that nodal spread may be bilateral, particularly with anterior and/or midline oral cavity tumors. Midline nodes are considered ipsilateral. Skip nodal metastases (level IV without level III involvement) while described with lateral tongue tumors, appear to be rare. As previously described, PET/CT may also be used to improve predictive yield for nodal metastases by the addition of physiologic information, and ultrasound may be an additive tool for evaluation of indeterminate nodes. PET/CT is the only modality to allow whole-body evaluation of distant metastatic spread, and the upper lungs and bone should always be reviewed as potential metastatic sites on any staging neck CT or MR imaging.

The risk of distant metastasis is more dependent on the N than on the T status of the head and neck cancer. In addition to the node size, number, and presence of ENE, regional lymph nodes also should be described according to the level of the neck that is involved. The level of involved nodes in the neck is prognostically significant for oral cavity (caudad nodal disease is worse), as is the presence of ENE from individual nodes. Imaging studies showing amorphous spiculated margins of involved nodes or involvement of internodal fat resulting in loss of normal oval-to-round nodal shape strongly suggest extranodal extension; however, pathological examination is necessary to prove its presence. No imaging study can currently identify minor ENE in metastatic nodes, microscopic foci of cancer in regional nodes or distinguish between small reactive nodes and small nodes with metastatic deposits (in the absence of central radiographic inhomogeneity).

Pathological Classification

Complete resection of the primary site and/or regional lymph node dissections, followed by pathological examination of the resection specimen allows for the use of this designation for pT and/or pN, respectively. Resections after radiation or chemotherapy should be identified and considered in context. pT is derived from the actual measurement of the unfixed tumor in the surgical specimen. It should be noted, however, that up to 30% shrinkage of soft tissues may occur in resected specimen after formalin fixation. Pathological staging represents additional and important information and should be included as such in staging, but it does not supplant clinical staging as the primary staging scheme. Metastasis found on imaging is considered cM1. Biopsy-proven metastasis is considered pM1.

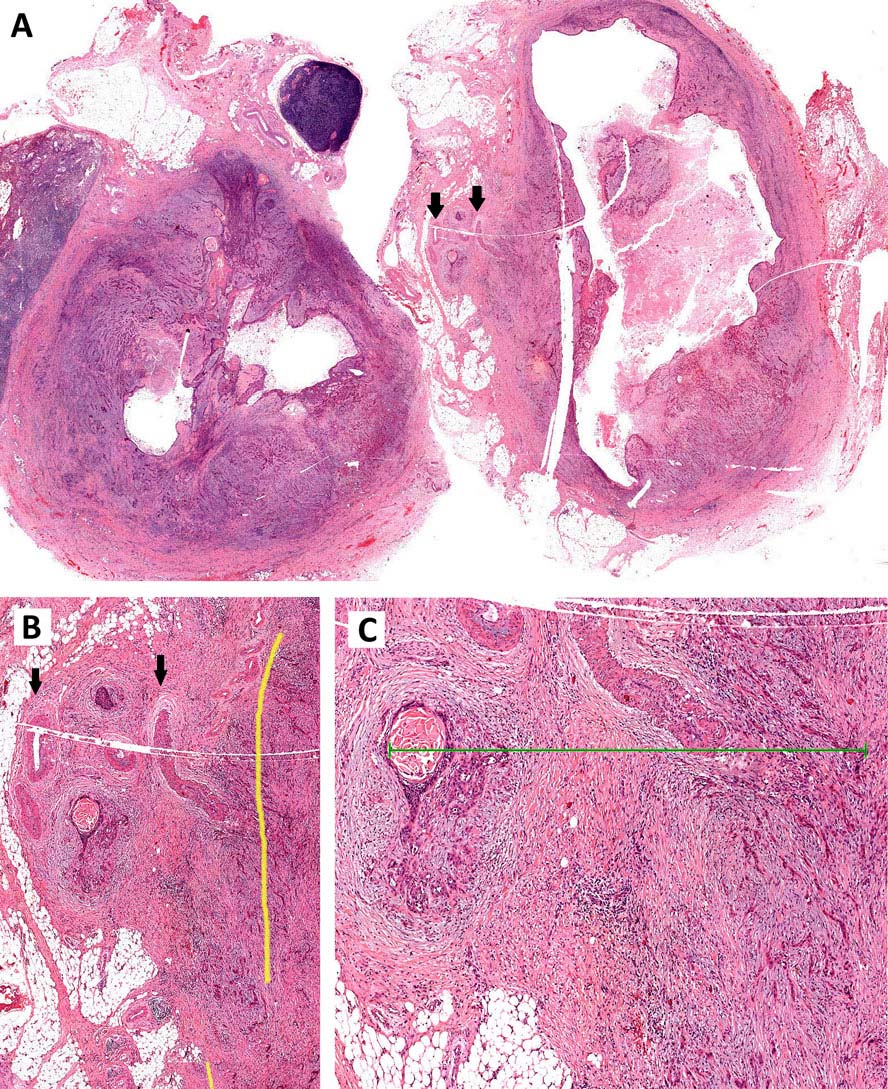

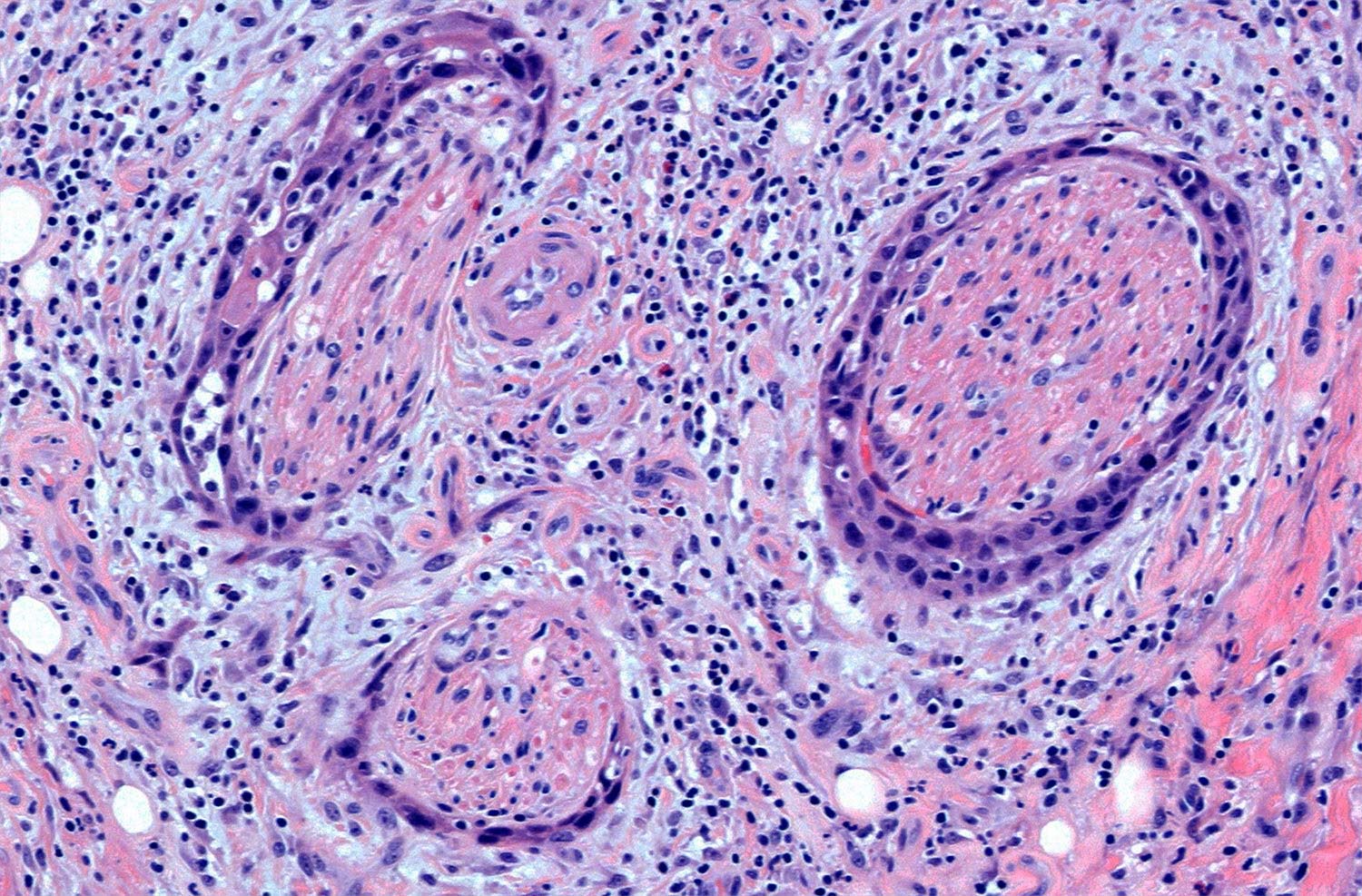

Pathological assessment of the primary tumor

Specimen prosection must separately address three issues: DOI, resection margins, and WPOI; it is best to submit different tissue cassettes documenting each prognosticator. DOI is assessed relative to adjacent normal mucosa. If carcinoma invades medullary bone, or subcutaneous tissues on gross examination, then it is categorized as T4 and DOI become irrelevant. The basic principle of resection margin assessment is that each tissue plane that meets the surgeon (bone, mucosa, soft tissue, vessels, and nerve) represents a resection margin and requires evaluation. Each specimen can be thought of as a multi-planed manifold; each cut surface from each orthogonal plane represents a margin surface. Ideally, margin assessment is performed as a comprehensive intraoperative process. Avoid parallel shave margins for mucosal/soft tissue assessment. The pitfall with shave margins is that they may be negative, but if on permanent sections cancer is present on deeper sections, the opportunity for measurements is lost. In the context of intraoperative assessment, the mucosal and soft tissue margins should be processed first, as these are actionable steps. Then process further tissue sections deliberately aimed to assess DOI and WPOI. WPOI sections are harvested from the tumor advancing edge at the soft tissue interface.

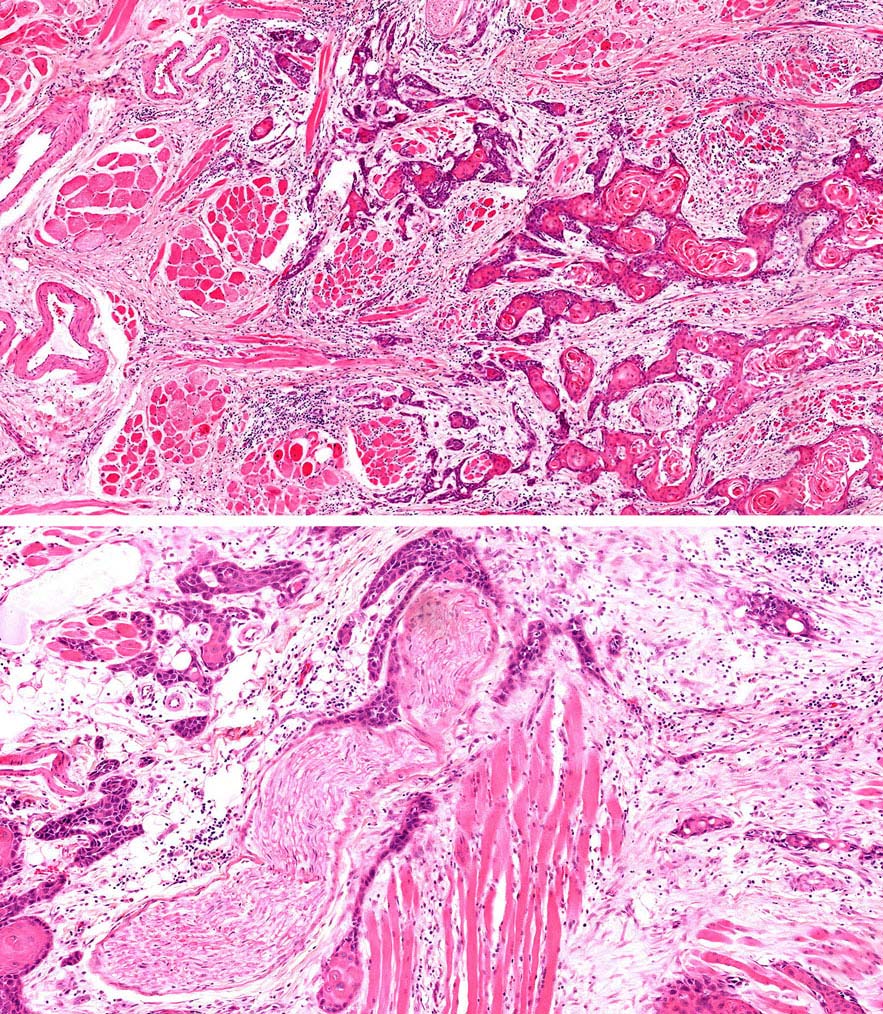

Pathological assessment of ENE

Resected positive lymph nodes require examination for the presence and extent of ENE. ENEmi is defined as microscopic ENE less than or equal to 2 mm. Macroscopic (ENEma) is defined as either extranodal extension apparent to the naked eye at the time of prosection and extension greater than 2 mm beyond the lymph node capsule microscopically. At the time of dissection, extranodal extension can be identified as irregular, firm, white/grey tumor at the interface with soft tissue. This still requires histologic documentation. The “naked eye” assessment is important if no residual lymph node structure can be found microscopically. By contrast, intact lymph node capsules are smooth, and separate easily from surrounding fat. ENEmi and ENEma are used to define pathological ENE(+) nodal status. Stretching of the lymph node capsule by carcinoma does not constitute ENE; microscopic evidence of breaching the capsule, with extension into surrounding soft tissue, with or without tissue reaction, constitutes ENE.

For assessment of pN, a selective neck dissection will ordinarily include 15 or more lymph nodes, and a comprehensive neck dissection (radical or modified radical neck dissection) will ordinarily include 22 or more lymph nodes. Examination of fewer tumor-free nodes still mandates a pN0 designation.

- ENE clinical (presence or absence)

- ENE pathological (presence or absence)

- Extent of microscopic ENE (distance of extension from the native lymph node capsule to the farthest point of invasion in the extranodal tissue)

- Perineural invasion

- Lymphovascular invasion

- p16/HPV status

- Performance status

- Tobacco use and pack-year

- Alcohol use

- Depression diagnosis

- Depth of invasion (mm)

- Margin status (grossly involved, microscopic involvement)

- Distance of tumor (or moderate/severe dysplasia) from closest margin

- WPOI-5