Note N: Regional Lymph Nodes

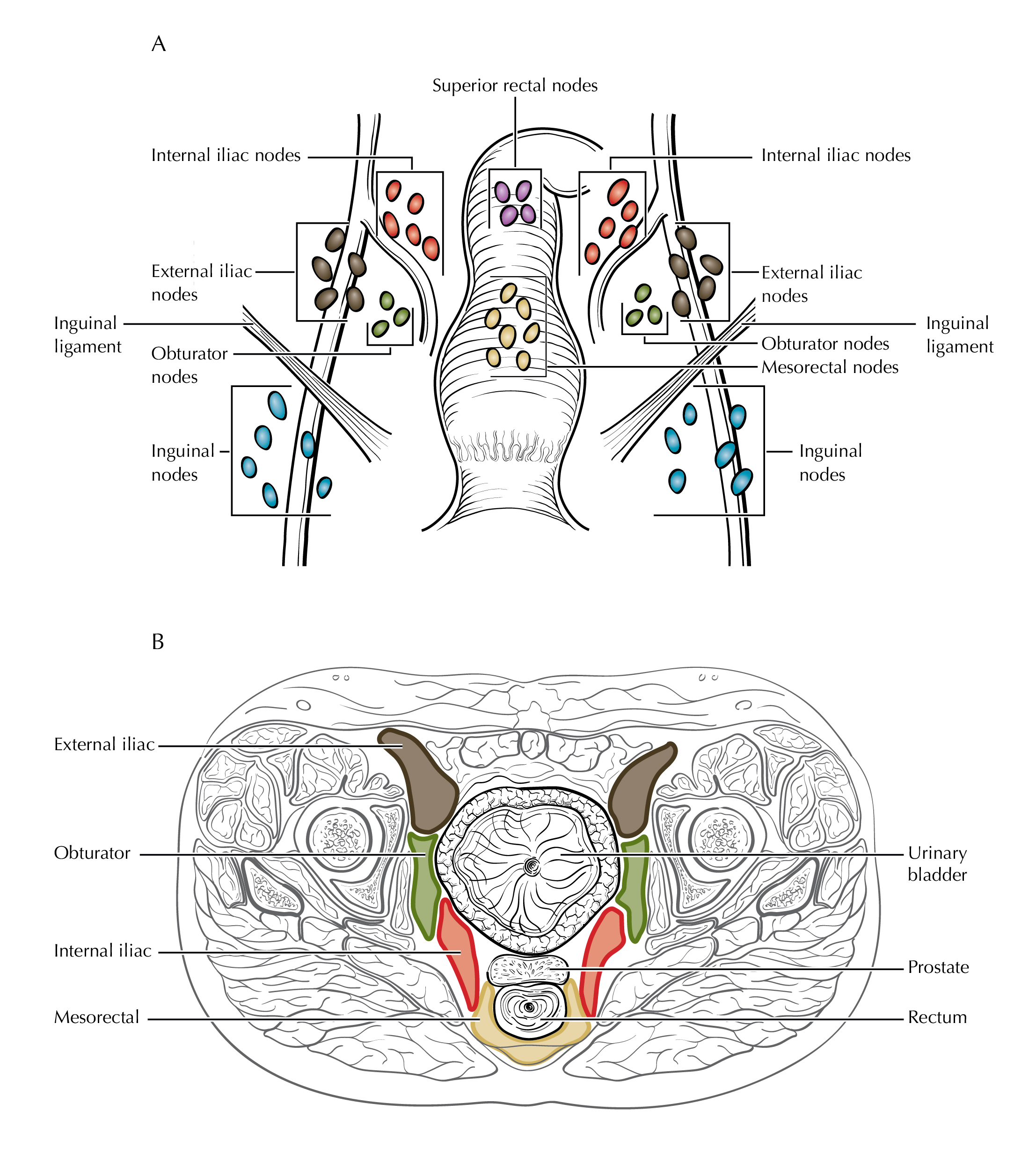

Lymphatic drainage and nodal involvement of anal cancers often depend on the location of the primary tumor. Tumors above the dentate line spread primarily to the mesorectal and internal iliac nodes, whereas tumors below the dentate line also may spread to the inguinal and external iliac nodes.

Assessment of lymph node involvement in anal cancer is even more challenging than in other cancers, where it has similarly been difficult to agree on radiographic criteria, because of the non-surgical nature of anal cancer preventing a surgical gold standard. Level I evidence is lacking for that reason. Many anal cancer articles included or are dominated by clinical follow up of nodes over time as a surrogate of involvement or not. Some include biopsies, such as from sentinel lymph node imaging or without this additional imaging. Furthermore, due to the demographics of this disease and its HPV association, men and women with HIV form an intersection of the affected population and may have non-specific HIV related lymphadenopathy further complicating interpretation.

Sizes and imaging appearances of nodes in CT and MR have been used for anal cancer as in other tumors and metabolic activity too is proposed through the use of PET scanning. In rectal cancer, a hybrid combination of these (The Dutch Consensus Criteria) have already shown more accurate staging and possibly safer patient outcomes.25 Possibly this will be the correct direction for anal cancer as well. Such a hybrid set of criteria was created for the non-HIV participants of the currently ongoing DECREASE trial (https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00056407) which incorporates PET and MRI (Table Anus-Suggested Definitions of Involved Lymph Nodes), but of course, the number of patients undergoing surgery will not be any greater than historically and so the lack of a pathologic gold standard still exists. However, this system can be considered as one created by a group of experts based on an exhaustive literature review and mainly extrapolation from higher level data available on other malignancies and might be generally recommended in the absence of a good alternative.

TABLE ANUS-SUGGESTED DEFINITION OF INVOLVED LYMPH NODES

| Anatomic Location | CT/MRI- based Size OR | CT/MRI-based Morphology OR | PET-based FDG Uptake |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mesorectal, Presacral | Short axis > 5mm | Irregular Border OR Central necrosis (only for LN > 3mm on MRI) | > Blood pool (Deauville 3-5) |

| Internal Iliac, Obturator | Short axis > 7mm | Irregular Border OR Central necrosis | > Blood pool (Deauville 3-5) |

| Common Iliac and External Iliac | Short axis > 10mm | Irregular Border OR Central necrosis | > Blood pool (Deauville 3-5) |

| Inguinal | No size criteria | Irregular Border OR Central necrosis | > Liver (Deauville 4-5) |

Note that the “Deauville Criteria” were created for 18F-FDG PET evaluation of lymphoma and have been borrowed here.26

Data using PET/CT for surgical nodal staging in other malignancies is extrapolated to anal cancer and revealed NPVs of 90-100% and PPVs of 43-100%.27-29 For mesorectal nodes, extrapolating from rectal cancer node-for-node validation studies, a combination of signal and border characteristics allowed a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 98%.30 PET adds specificity to MRI for involved mesorectal nodes in anal cancer when there is greater FDG uptake than normal tissues (PPV = 84%).31 For inguinal nodes, combining PET/CT and sentinel lymph node biopsy it was shown that size is an unreliable criterion in 123 nodes that were removed with negative nodes size average 1.16 cm and positive nodes

size average of 1.19 cm.28 Regarding inguinal nodes in HIV+ patients; symmetric enlargement has been found more often (100%) than when compared with non-HIV patients (<50%).32

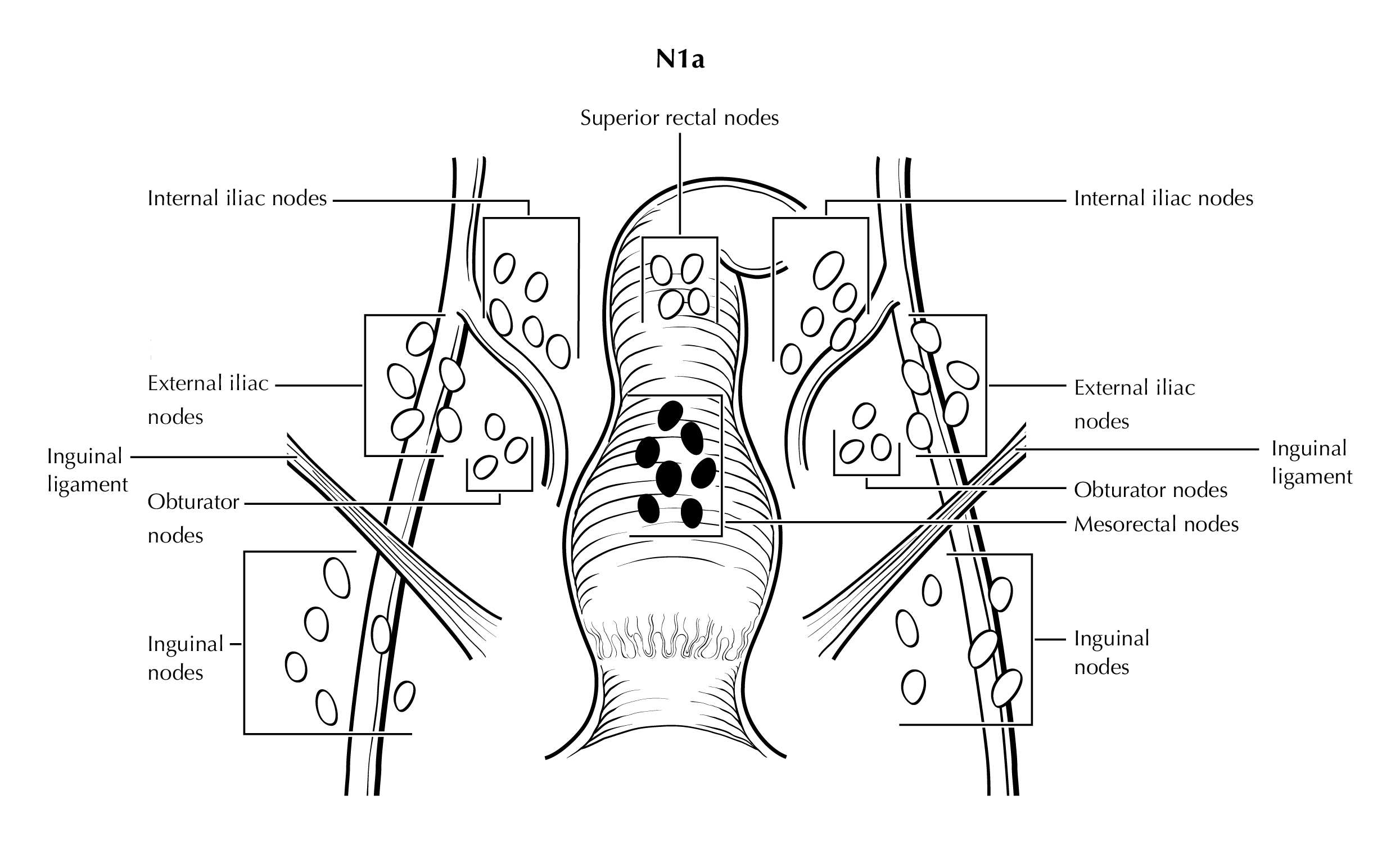

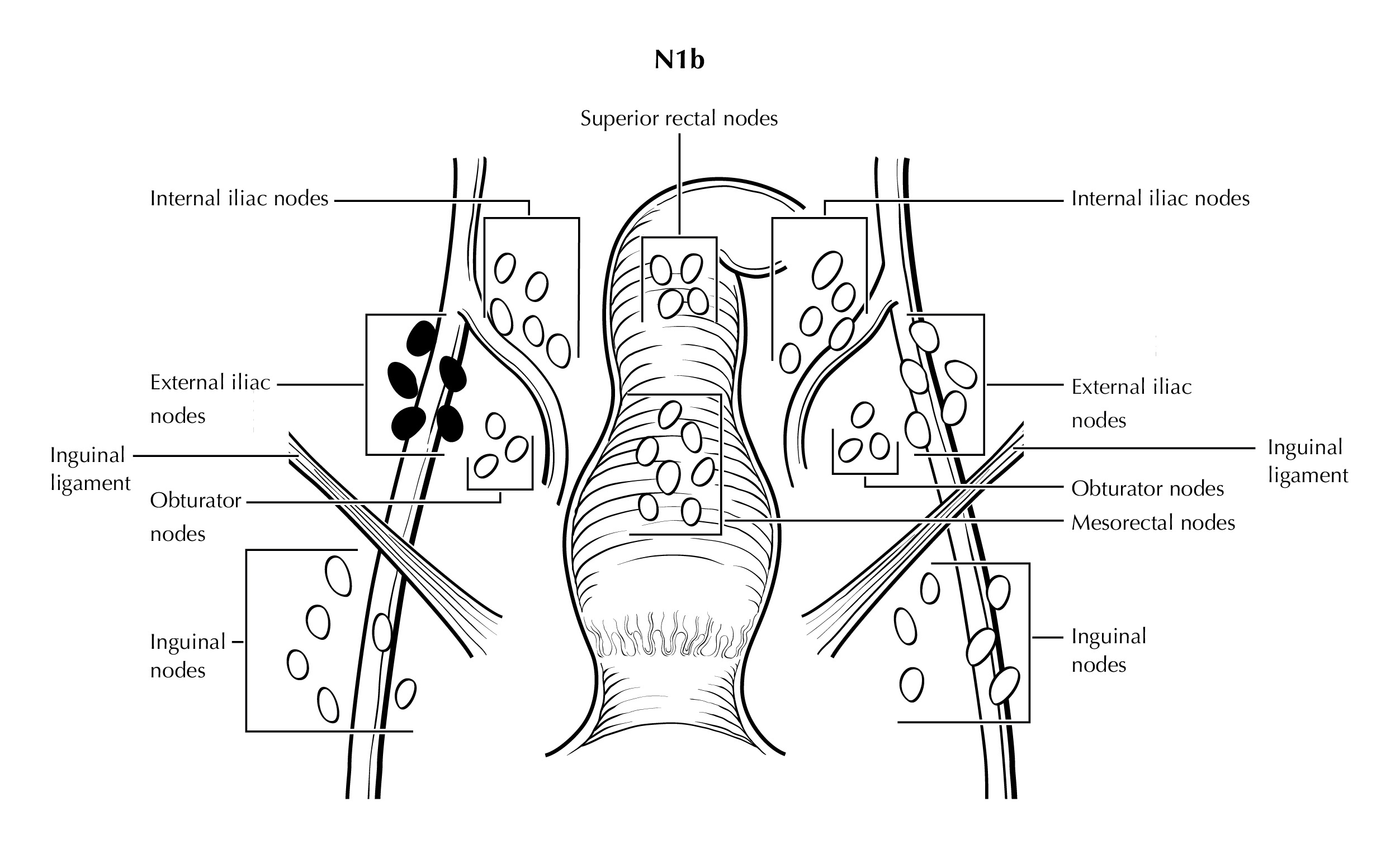

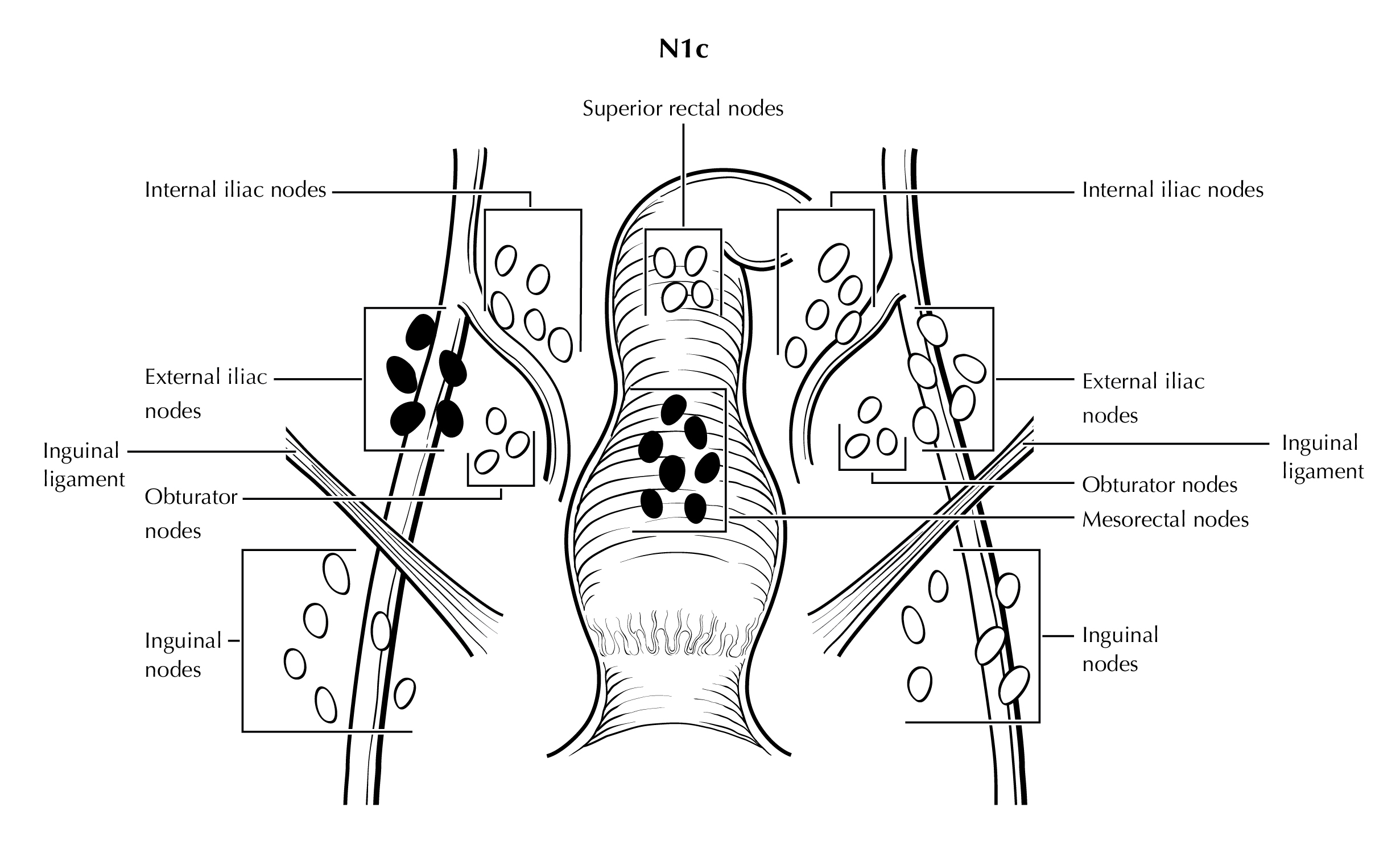

The regional lymph nodes are as follows (Figure Anus-Nodal Map):

Mesorectal

Inguinal

Superior rectal (hemorrhoidal)

External iliac

Internal iliac

Obturator

All other nodal groups represent sites of distant metastasis.

If the vessel wall or its remnant is identifiable on H&E, elastin, or any other stain, the lesion should be classified as lymphovascular invasion (LVI) present (a CAP-required data element).

FIGURE ANUS-NODAL MAP. Schematic of regional draining lymph nodes for tumors of the anus, coronal view (A). Depiction of cross-sectional imaging of regional lymph nodes in the pelvis (B).

FIGURE ANUS-N1a. N1a is defined as tumor involvement of inguinal, mesorectal (as illustrated), superior rectal, internal iliac, or obturator lymph nodes.

FIGURE ANUS-N1b. N1b is defined as tumor involvement of external iliac lymph nodes.

FIGURE ANUS-N1c. N1c is defined as tumor involvement of external iliac (N1b) with any N1a nodes (mesorectal nodes are illustrated).

Identification of Primary Site (Note S)

NOTE: This list includes topography codes and terms from the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O).2

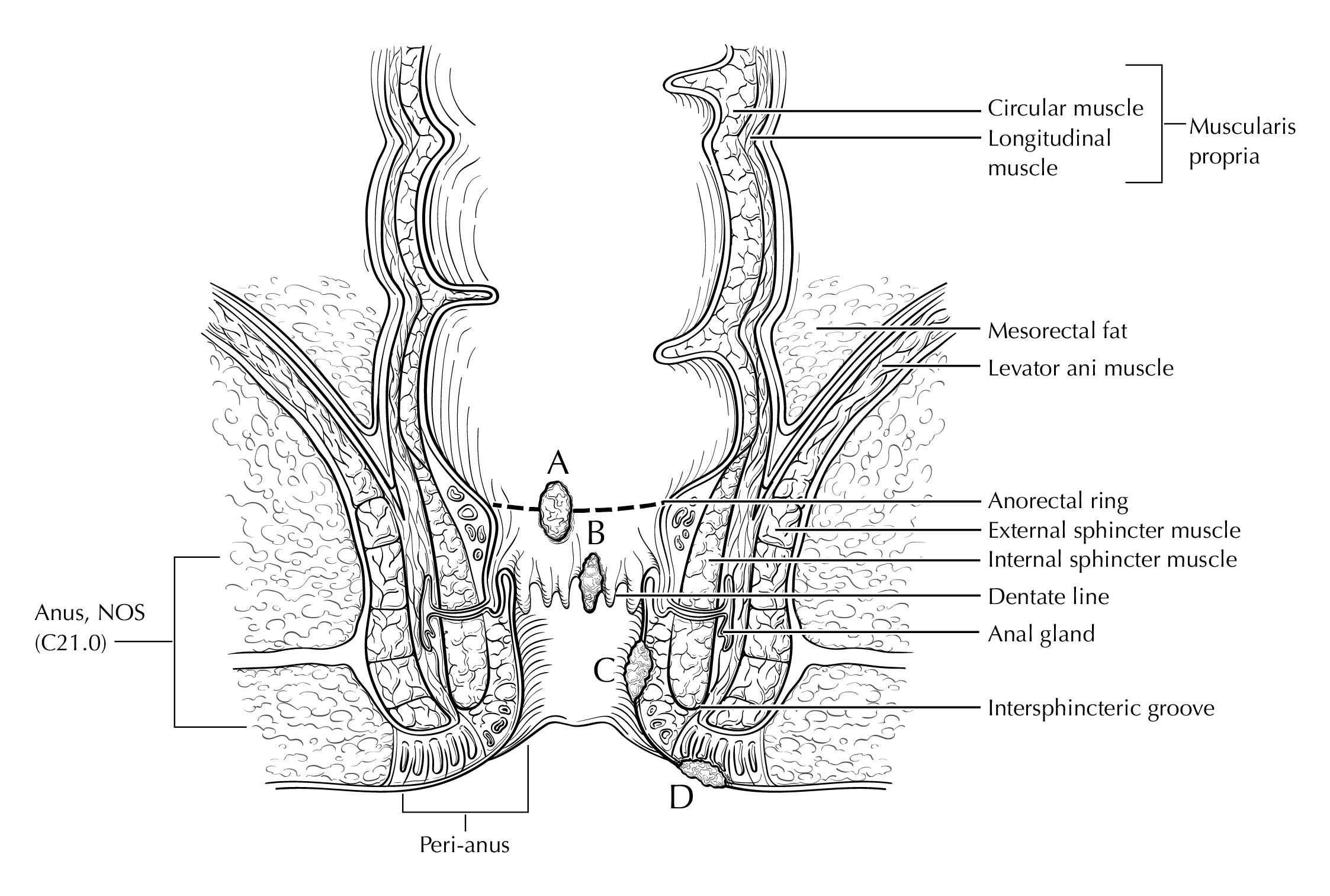

Note S: Identification of Primary Site

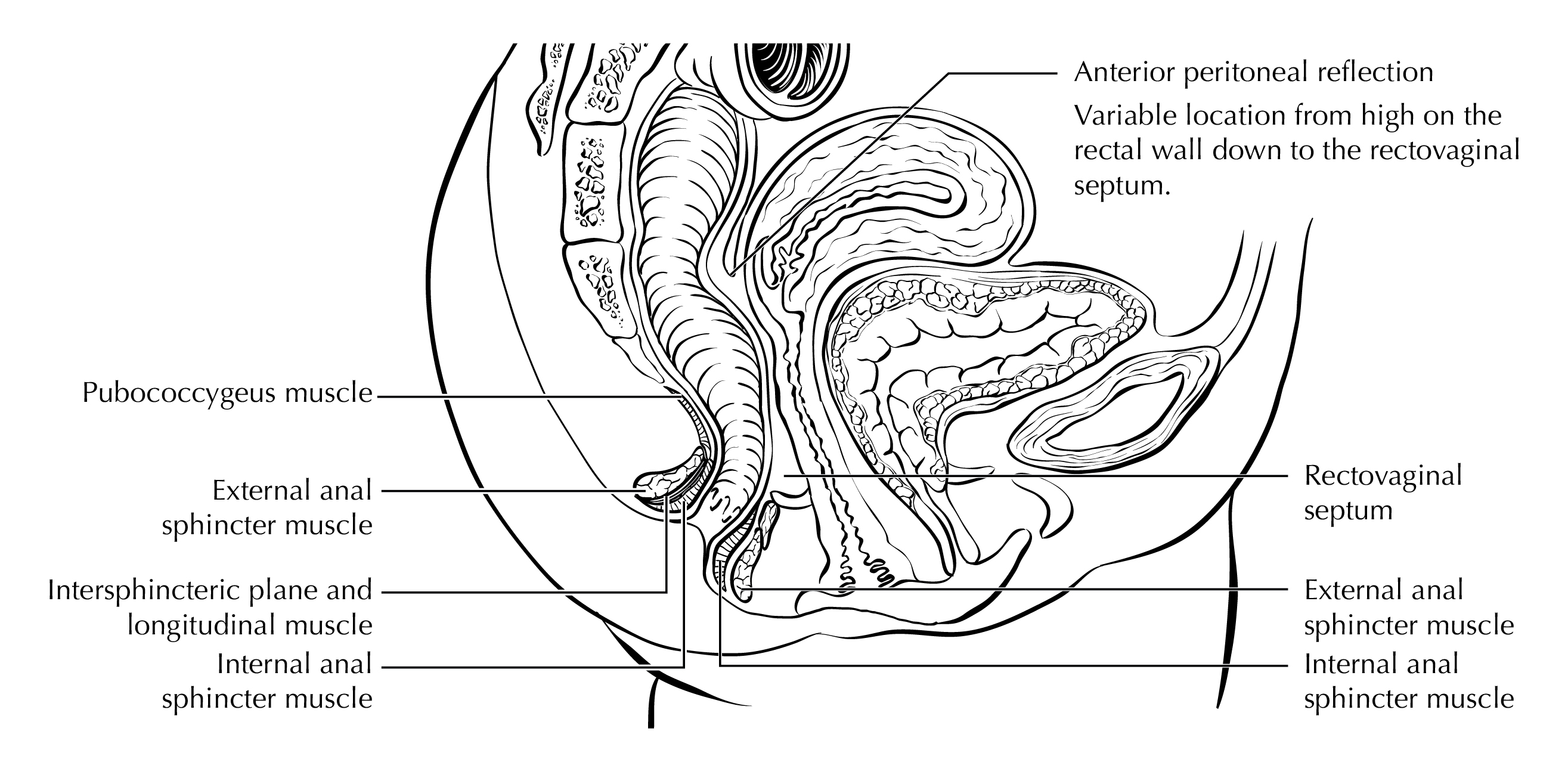

The anus is the distal opening to the lower gastrointestinal tract (Figure Anus-Anatomy Coronal and Figure Anus-Anatomy Sagittal Female). The anal canal begins where the rectum enters the puborectalis sling at the apex of the anal sphincter complex (palpable as the anorectal ring on digital rectal examination and approximately 1 to 2 cm proximal to the dentate line). The anus ends with the squamous mucosa blending with the perianal skin, which coincides roughly with the palpable intersphincteric groove or the outermost boundary of the internal sphincter muscle, easily visualized on endoanal ultrasound. The anus encompasses true mucosa of three different histologic types: colorectal-type glandular, transitional, and squamous (proximal to distal, respectively). The most proximal aspect of the anal canal is lined by a continuation of the colorectal mucosa. The anal transitional zone (ATZ) is interposed between this colorectal zone and the distal squamous zone. The ATZ mucosa variably consists of discontinuous islands of squamous and rectal glandular epithelium, immature squamous metaplasia and a multi-layered transitional epithelium. The anal glands arise in the ATZ and may extend into the internal sphincter smooth muscle. The squamous (distal) zone of the anal canal extends from the dentate line to the mucocutaneous junction with the perianal skin and is lined by a nonkeratinizing squamous epithelium devoid of epidermal appendages (hair follicles, apocrine glands, and sweat glands).

Tumors that develop from mucosa (of any of the three types) that cannot be visualized in their entirety while gentle traction is placed on the buttocks are termed anal cancers, whereas those that arise within the skin at or distal to the squamous mucocutaneous junction, can be seen in their entirety with gentle traction placed on the buttocks, and are within 5 cm of the anus are termed perianal cancers.

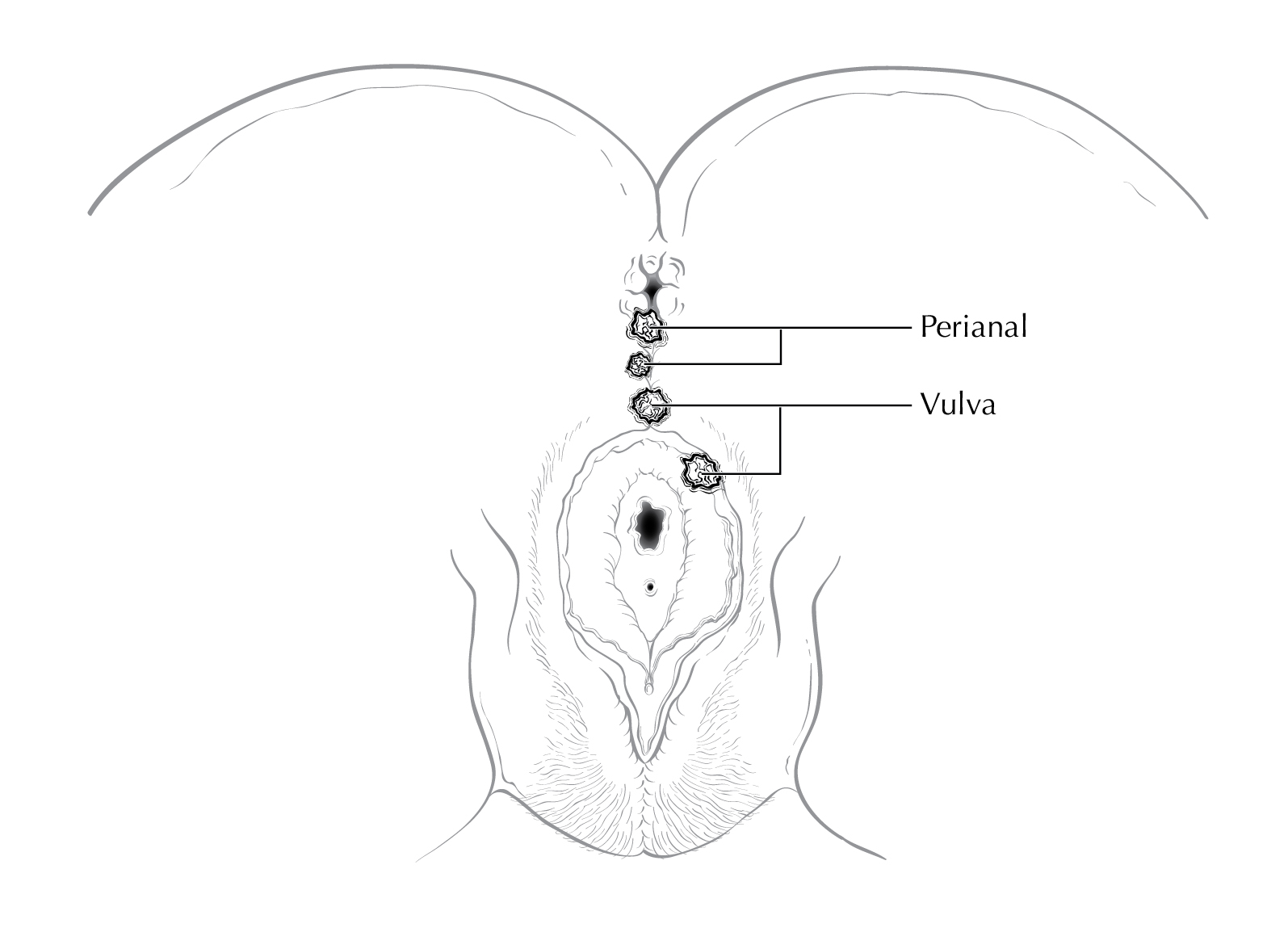

Squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) overlying the perineal body may be classified as perianal or vulvar, and the treatment plans may be quite dissimilar. For this reason, we recommend the following: lesions that clearly arise from the vulva and extend onto the perineum and potentially involve the anus should be classified as vulvar. Similarly, lesions that clearly arise from the distal anal squamous mucosa and extend onto the perineum should be classified as perianal. Lesions localized to the perineum that are not clearly arising from either the vulva or the anus should be categorized based on the clinician’s clinical impression. Thus, we recommend the following terminology: perineum favor vulva and perineum favor perianus. We also recommend consulting with colleagues in gynecologic oncology, colorectal or general surgery, or surgical oncology, because classification has a significant impact on treatment.

FIGURE ANUS-ANATOMY CORONAL. Anus and surrounding structures. Anal cancers (A-C) and peri-anal cancer (D).

FIGURE ANUS-ANATOMY SAGITTAL FEMALE. Anus with surrounding structures.

FIGURE ANUS-SURFACE LESIONS MALE. Anal and perianal lesions staged with this protocol. Skin cancers are not staged with this protocol. The diagram demonstrates a tumor straddling anal verge (anal), a tumor within 5 cm of anal verge (perianal), and a tumor >5 cm from anal verge (skin).

FIGURE ANUS-SURFACE LESIONS FEMALE. Anatomic site distinctions between perianal and vulva.

Note T: Primary Tumor (T)

The anatomy of the anus is described in Note S: Identification of Primary Site with a figure of the anatomy.

In the AJCC 8th edition staging system of anal cancer, the disease was staged as Stage 0 when the lesion is “in situ” (Tis), meaning that it is entirely intra-epithelial and has not crossed the basement membrane, i.e., is not invasive cancer. In addition, Tis lesions have not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or distant sites (M0). Tis lesions are considered to be a form of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) which, like other HSIL lesions may progress to cancer if left untreated but are themselves not malignant.5 Use of the term “carcinoma in situ” may lead to confusion through the use of the word “carcinoma”, which has led to some patients being erroneously treated with protocols for bona fide cancers, including chemo-and/or radiation therapy. Inclusion of the Tis in the TNM staging system may also lead clinicians to incorrectly believe that these pre-malignant lesions are malignant and need to be treated as such. In contrast, patients with Tis lesions may benefit from local removal to prevent progression to cancer. The Anal Cancer/HSIL Outcomes Research (ANCHOR) Study recently reported that treatment of anal HSIL, consisting primarily of local ablation, reduces the risk of progressing to anal cancer compared with no treatment. There are no reliable data on survival after treatment of Tis lesions. There is no routine, standard of care screening system for Tis lesions and reporting of these lesions is not reliable. Thus, in the AJCC Version 9 of the Anus Protocol, Stage 0 has been removed.

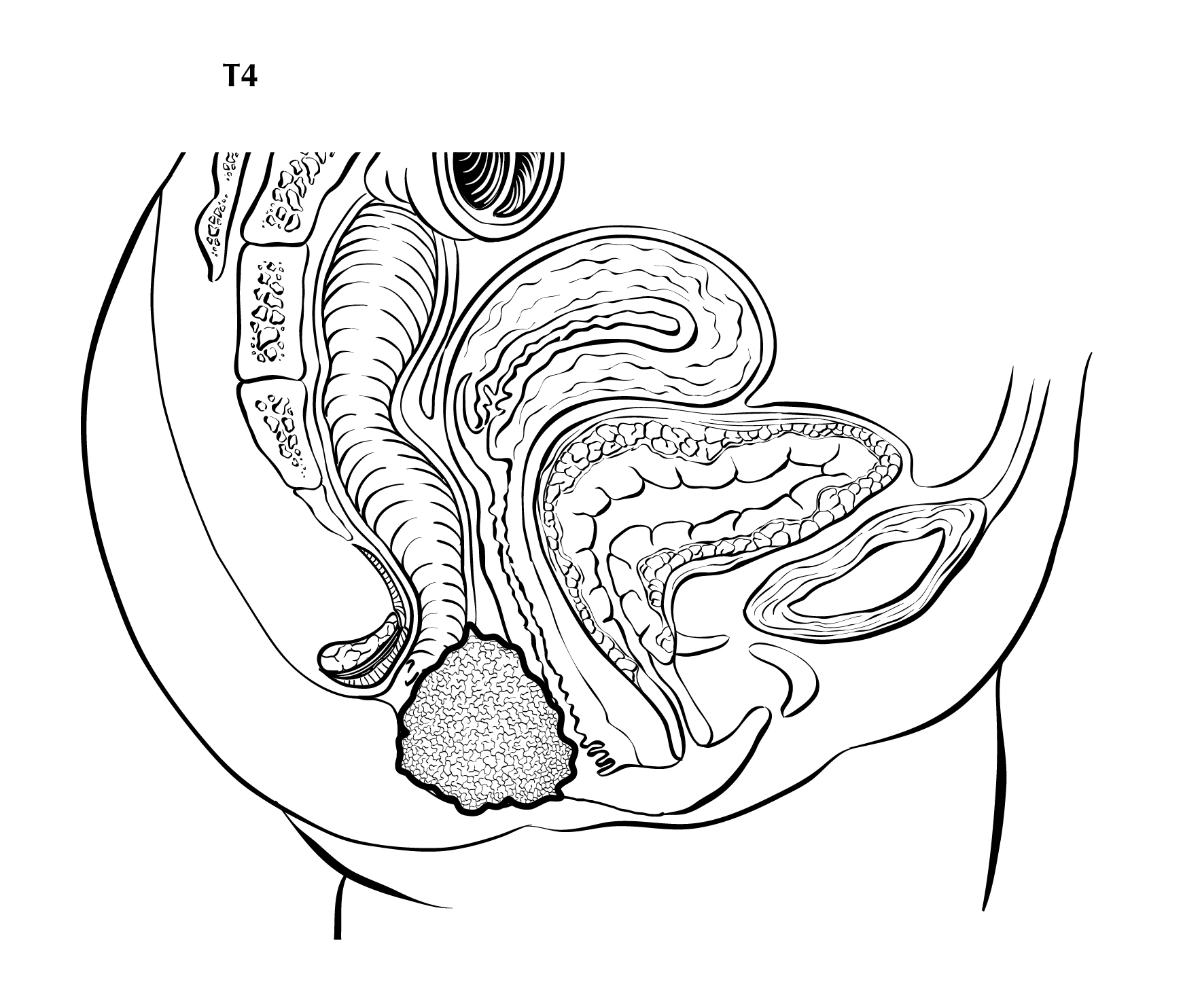

Of note, direct invasion of the rectal wall, perianal skin, subcutaneous tissue or the anal sphincter muscles is not classified as T4.

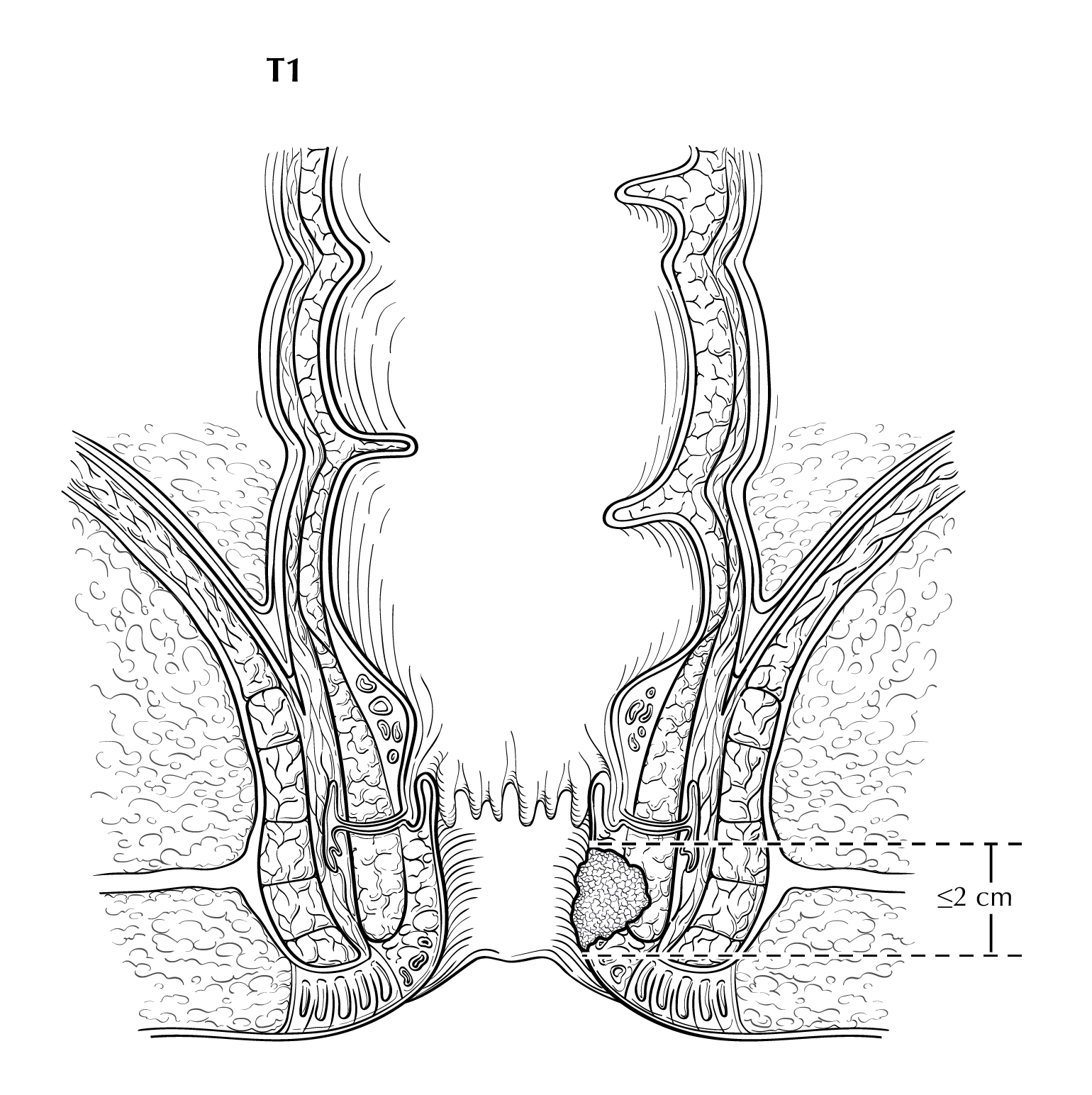

FIGURE ANUS-T1. T1 is defined as tumor that is less than or equal to 2 cm in greatest dimension.

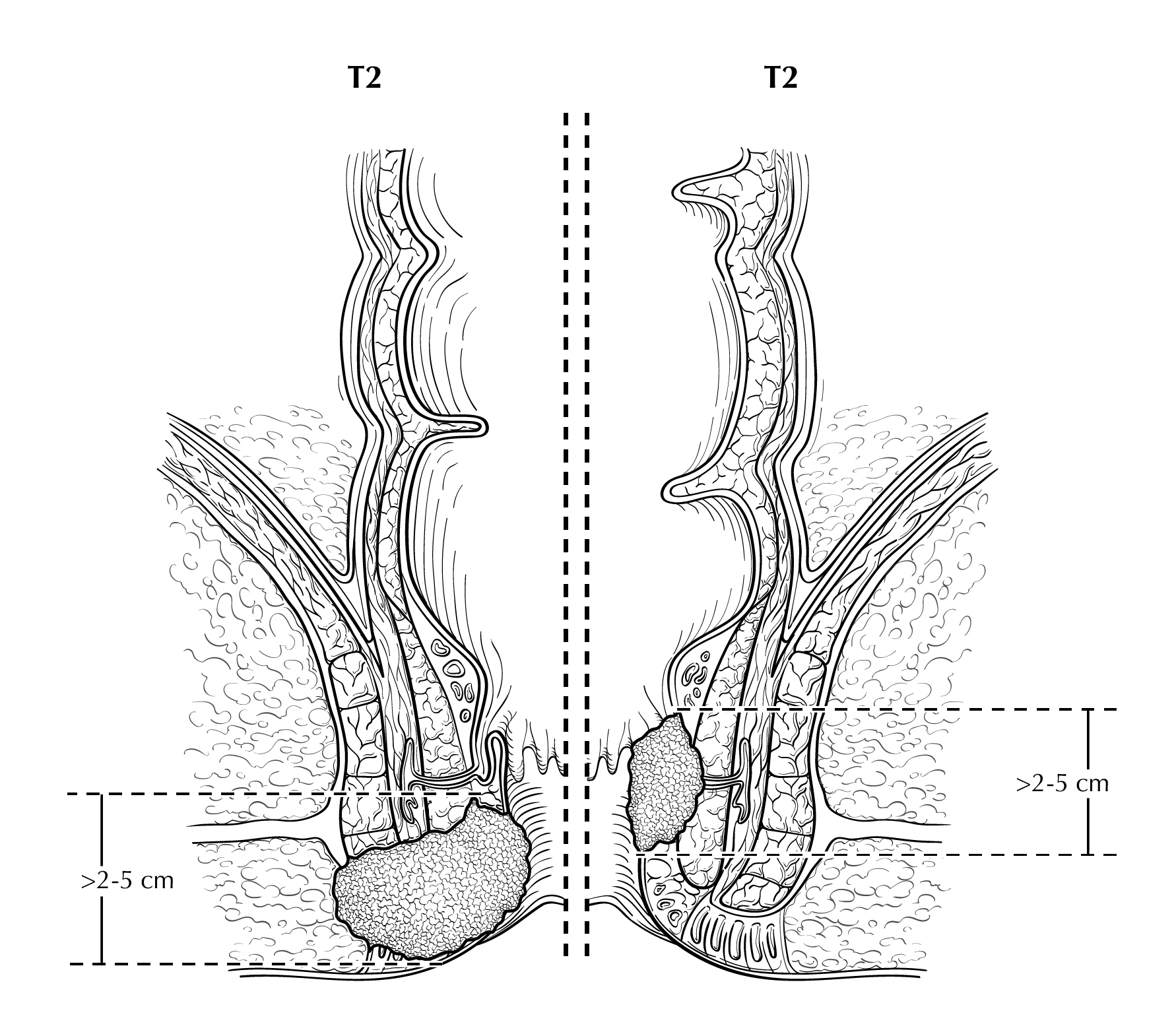

FIGURE ANUS-T2. Two views of T2 showing tumor that is greater than 2 cm but less than or equal to 5cm in greatest dimension. On the right side of the diagram, the tumor extends above the dentate line.

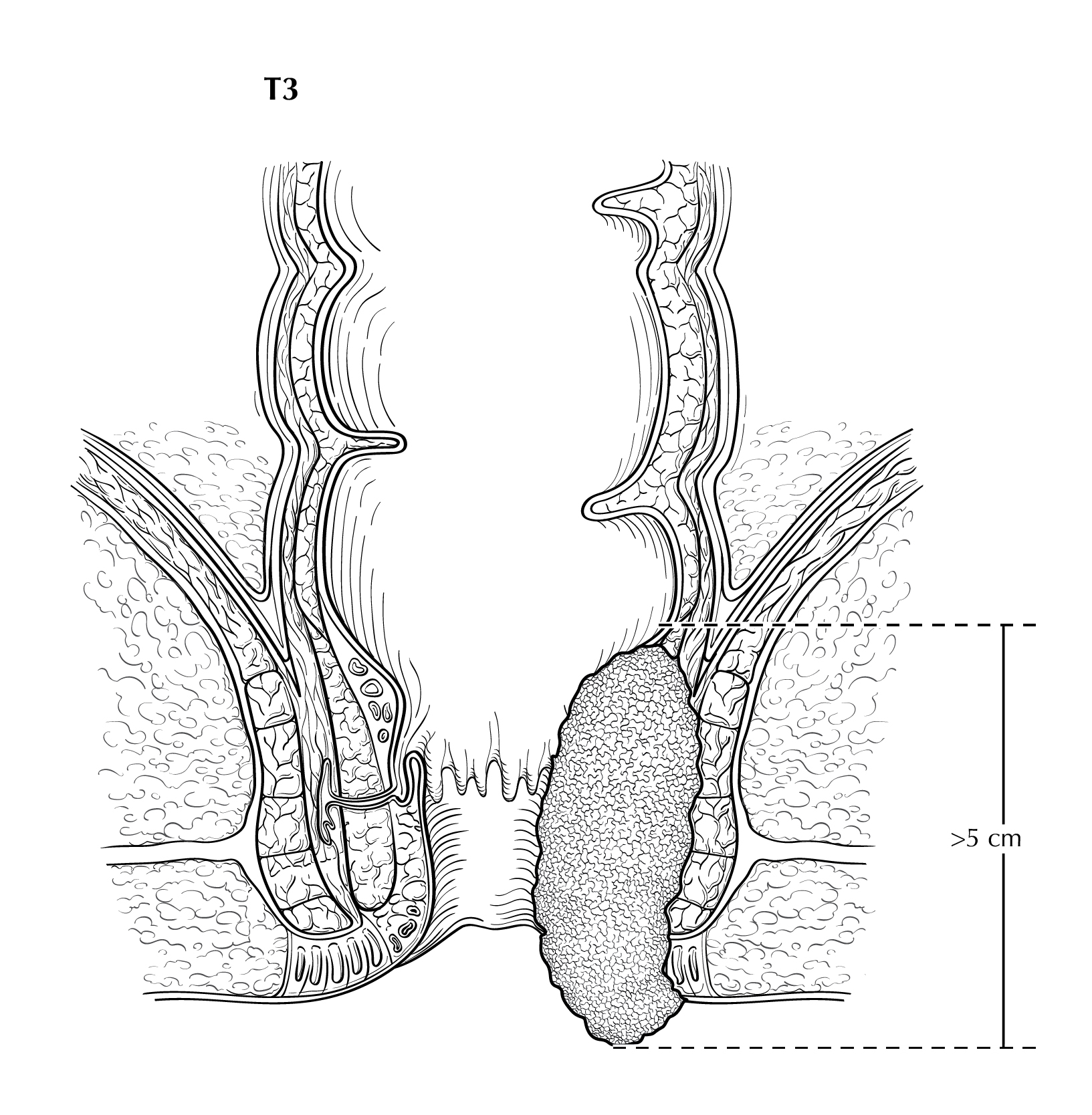

FIGURE ANUS-T3. T3 is defined as tumor that is greater than 5 cm in greatest dimension.

FIGURE ANUS-T4. T4 is defined as tumor of any size invading adjacent organ(s), such as the vagina (as illustrated), urethra, and bladder.