Introduction to TNM Staging Classification

Stage may be defined at several time points in the care of the cancer patient. To properly stage a patient's cancer, it is essential to first determine the time point in a patient's care. These points in time are termed classifications and are based on time during the continuum of evaluation and management of the disease. Then, T, N, and M categories are assigned for a particular classification (clinical, pathological, posttherapy, recurrence, and/or autopsy) by using information obtained during the relevant time frame, sometimes also referred to as a staging window. These staging windows are unique to each particular classification and are set forth explicitly in the Supplemental Information. The prognostic stage groups then are assigned using the T, N, and M categories, and sometimes also site-specific prognostic and predictive factors.

Among these classifications, the two predominant are clinical classification (i.e., pretreatment) and pathological classification (i.e., after surgical treatment as initial therapy).

Note C: Rules for Clinical TNM Classification

Clinical stage classification is based on patient history, physical examination, and any imaging done before initiation of treatment. Imaging study information may be used for clinical staging, but clinical stage may be assigned based on whatever information is available. No specific imaging is required to assign a clinical stage for any cancer site. When performed within this framework, biopsy information on regional lymph nodes and/or other sites of metastatic disease may be included in the clinical classification.

See General Staging Rules Table and Stage Classifications Table in Supplemental Information for additional guidance, including the time frame/staging window for determining clinical stage.

Clinical stage is important to record for all patients because:

- clinical stage is essential for selecting initial therapy, and

- clinical stage is critical for comparison across patient cohorts when some have surgery as a component of initial treatment and others do not.

Clinical stage may be the only stage classification by which comparisons can be made across all patients, because not all patients will undergo surgical treatment before other therapy, and response to treatment varies. Differences in primary therapy make comparing groups of patients difficult if that comparison is based on pathological assessment. For example, it is difficult to compare patients treated with primary surgery with those treated with chemotherapy or radiation therapy without surgery or neoadjuvant therapy.

Clinical classification is based on evidence acquired from the date of diagnosis until initiation of primary treatment. Examples of primary treatment include definitive surgery, radiation therapy, systemic therapy, and neoadjuvant radiation and systemic therapy.

Clinical Classification

Clinical assessment is based on medical history, clinical examination, imaging, and biochemical assessment. If a biopsy is performed, the results should be incorporated when assigning clinical stage.

Note P: Rules for Pathologic TNM Classification

Classification of T, N, and M after surgical treatment is denoted by use of a lowercase p prefix: pT, pN, and cM0, cM1, or pM1. The purpose of pathological classification is to provide additional precise and objective data for prognosis and outcomes, and to guide subsequent therapy.

Pathological stage classification is based on clinical stage information supplemented/modified by operative findings and pathological evaluation of the resected specimens. This classification is applicable when surgery is performed before initiation of adjuvant radiation or systemic therapy.

See General Staging Rules Table and Stage Classifications Table in Supplemental Information for additional guidance.

Pathological Classification

Pathological staging is based on surgical resection specimens. The most sensitive pathological staging is obtained by examining surgically resected primary tumor(s), lymph nodes, and distant metastases according to an established minimum pathology dataset whenever possible adopting standard synoptic reporting protocols.9,57-61

Note YC: Rules for Posttherapy Clinical TNM Classification

Stage determined after treatment for patients receiving systemic and/or radiation therapy alone or as a component of their initial treatment, or as neoadjuvant therapy before planned surgery, is referred to as posttherapy classification. It also may be referred to as post neoadjuvant therapy classification.

See General Staging Rules Table and Stage Classifications Table in Supplemental Information for additional guidance.

Observed changes between the clinical classification and the posttherapy classification may provide clinicians with information regarding the response to therapy. The clinical extent of response to therapy may guide the scope of planned surgery, and the clinical and pathological extent of response to therapy may provide prognostic information and guide the use of further adjuvant radiation and/or systemic therapy.

Classification of T, N, and M after systemic or radiation treatment intended as definitive therapy is denoted by use of a lowercase yc prefix: ycT, ycN, c/pM. The c/pM category may include cM0, cM1, or pM1. The post neoadjuvant therapy assessment of the T and N (yTNM) categories uses specific criteria. In contrast, the M category for post neoadjuvant therapy classification remains the same as that assigned in the clinical stage before initiation of neoadjuvant therapy (e.g., if there is a complete clinical response to therapy in a patient previously categorized as cM1, the M1 category is used for final yc and yp staging).

See Stage Classifications Table in Supplemental Information for additional guidance.

Posttherapy Clinical Classification

Neoadjuvant treatment is rarely performed for neuroendocrine tumors.

Note YP: Rules for Posttherapy Pathological TNM Classification

Classification of T, N, and M after systemic or radiation neoadjuvant treatment followed by surgery is denoted by use of a lowercase yp prefix: ypT, ypN, c/pM. The c/pM category may include cM0, cM1, or pM1. The post neoadjuvant therapy assessment of the T and N (yTNM) categories uses specific criteria. In contrast, the M category for post neoadjuvant therapy classification remains the same as that assigned in the clinical stage before initiation of neoadjuvant therapy (e.g., if there is a complete clinical response to therapy in a patient previously categorized as cM1, the M1 category is used for final yc and yp staging).

The time frame for assignment of ypT and ypN should be such that the post neoadjuvant therapy surgery and staging occur within a period that accommodates disease-specific circumstances.

Criteria: First therapy is systemic and/or radiation therapy followed by surgery.

y-pathological (yp) classification is based on the:

- y-clinical stage information, and supplemented/modified by

- operative findings, and

- pathological evaluation of the resected specimen.

Examples of treatments that satisfy the definition of neoadjuvant therapy may be found in sources such as the NCCN Guidelines, ASCO guidelines, or other treatment guidelines. Systemic therapy includes chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and immunotherapy. Not all medications given to a patient meet the criteria for neoadjuvant therapy (e.g., a short course of therapy that is provided for variable and often unconventional reasons, should not be categorized as neoadjuvant therapy).

See Stage Classifications Table in Supplemental Information for additional guidance.

Posttherapy Pathological Classification

Neoadjuvant treatment is rarely performed for neuroendocrine tumors.

Note R: Rules for Recurrence/Retreatment TNM Classification

Staging classifications at the time of retreatment for a recurrence or disease progression is referred to as recurrence classification. It also may be referred to as retreatment classification. Classification of T, N, and M for recurrence or retreatment is denoted by use of the lowercase r prefix: rcT, rcN, rc/rpM, and rpT, rpN, rc/rpM. The rc/rpM may include rcM0, rcM1, or rpM1.

See Stage Classifications Table in Supplemental Information for additional guidance.

Note A: Rules for Autopsy TNM Classification

Staging classification for cancers identified only at autopsy is referred to as autopsy classification. This classification is used when cancer is diagnosed at autopsy and there was no prior suspicion or evidence of cancer before death. All clinical and pathological information obtained at the time of death and through post-mortem examination is included. Classification of T, N, and M at autopsy is denoted by use of the lowercase a prefix: aT, aN, aM.

See Stage Classifications Table in Supplemental Information for additional guidance.

Note CE: Clinical Examination

Guidelines have been established for the workup of patients with PanNETs.29,44,46 In general, patients should be evaluated by multiphasic computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging to assess: 1) the proximity of the primary pancreatic NET to major vessels and 2) the clinical T, N, and M staging of the lesion before any surgical or medical therapy is considered. In addition, biochemical assessment, Ga68-SRS-PET or somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS), and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) should be performed as appropriate. EUS provides useful information for detection of small and/or multifocal PanNETs and is the procedure of choice for performing fine-needle aspiration or fine needle biopsy of the pancreas. Studies suggest detection rates of 90-100% for pancreatic lesions.47 For localized tumors, a biopsy is not necessarily required before surgical resection. However, if a biopsy (e.g., endoscopic biopsy, percutaneous core needle biopsy, fine-needle aspiration) is performed, the results should be incorporated when assessing clinical stage.

By definition, patients with F-PanNETs present with hormone-mediated symptoms consistent with a characteristic syndrome.16,29,30 As such, the diagnosis of F-PanNETs requires demonstration of a significantly elevated hormone combined with clinical signs or symptoms of hypersecretion with a specific endocrinological workup.29,30

Assessment for hormones associated with rarer syndromes should be performed as clinically indicated.14

Unless incidentally discovered during a workup for an unrelated problem, NF-PanNETs present with symptoms due to the tumor itself, including abdominal pain, weight loss, or jaundice.13,48,49 NF-PanNETs may secrete peptides, such as CgA and the chromogranin fraction pancreastatin, PP, neuron-specific enolase, which may be helpful for the diagnosis and monitoring of affected patients.13,48 Recently, a nuclei acid-based NETtestR has also been developed with possible prognostic implications.50

Note I: Imaging

Information necessary for the clinical staging of pancreatic NETs may be obtained from physical examination; cross-sectional radiographic imaging studies, including triphasic (non-contrast, arterial, and venous) contrast-enhanced CT or MR imaging; and molecular imaging using SSTR-PET51 (refer to established guidelines for details).29 In particular, CT is best for anatomic staging of the primary tumor and for surgical planning, while MRI, and in particular hepatobiliary phase MRI is best suited for detecting and following disease in the liver.31,52,53 SSTR-PET has the highest detection rate for metastatic disease for neuroendocrine tumors and provides several other advantages including same-day results, potential for increased sensitivity compared to anatomical imaging, broader affinity profile, better spatial resolution, and easier quantification of tracer uptake.54,55,56 There are three US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved SSTR-PET imaging agents: 68Ga-DOTATATE (NetSpot, AAA/Novartis), 68Ga-DOTATOC, and 64Cu-DOTATATE (Detectnet, Curium). If avoidable, imaging should no longer be performed with the older radiopharmaceutical indium-111 pentetreotide (Octreoscan, Curium) which has much lower resolution than PET in addition to other disadvantages related to radiation exposure and imaging time. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET has limited value in the evaluation of low-grade PanNETs, but has an important role in higher grade tumors where it can outperform SSTR-PET due to a downregulation of SSTRs.

Unlike its exocrine counterpart (pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma), tumor involvement of the major visceral arteries (i.e. celiac axis or superior mesenteric artery) is rare in PanNETs. The standard radiographic assessment of resectability includes evaluation for distant metastases (e.g., peritoneal, liver, bone); the patency of the superior mesenteric vein and portal vein, as well as the relationship of these vessels and their tributaries to the tumor; and the relationship of the tumor to the superior mesenteric artery, celiac axis, and hepatic artery.

General Staging Rules

These general rules apply to the application of T, N, and M categories for all anatomic sites and classifications.

| Topic | Rules |

Microscopic confirmation | - Microscopic confirmation is necessary for TNM classification, including clinical classification (with rare exception).

- In rare clinical scenarios, patients who do not have any biopsy or cytology of the tumor may be staged. This is recommended in rare clinical situations, only if the cancer diagnosis is NOT in doubt. In the absence of histologic confirmation, survival analysis may be performed separately from staged cohorts with histologic confirmation. Separate survival analysis is not required if clinical findings support a cancer diagnosis and specific site.

Example: Lung cancer diagnosed by CT scan only, that is, without a confirmatory biopsy |

Time frame/staging window for determining clinical stage | Information gathered about the extent of the cancer is part of clinical classification: - from date of diagnosis before initiation of primary treatment or decision for watchful waiting or supportive care to one of the following time points, whichever is shortest:

- 4 months after diagnosis

- to the date of cancer progression if the cancer progresses before the end of the 4 month window; data on the extent of the cancer is only included before the date of observed progression

|

Time frame/staging window for determining pathological stage | Information including clinical staging data and information from surgical resection and examination of the resected specimens—if surgery is performed before the initiation of radiation and/or systemic therapy—from the date of diagnosis: - within 4 months after diagnosis

- to the date of cancer progression if the cancer progresses before the end of the 4-month window; data on the extent of the cancer is included only before the date of observed progression

- and includes any information obtained about the extent of cancer up through completion of definitive surgery as part of primary treatment if that surgery occurs later than

4 months after diagnosis and the cancer has not clearly progressed during the time window Note: Patients who receive radiation and/or systemic therapy (neoadjuvant therapy) before surgical resection are not assigned a pathological category or stage, and instead are staged according to post neoadjuvant therapy criteria. |

Time frame/staging window for staging post neoadjuvant therapy or posttherapy | After completion of neoadjuvant therapy, patients should be staged as: - yc: posttherapy clinicalAfter completion of neoadjuvant therapy followed by surgery, patients should be staged as:

- yp: posttherapy pathological

The time frame should be such that the post neoadjuvant surgery and staging occur within a time frame that accommodates disease-specific circumstances, as outlined in the specific disease sites and in relevant guidelines. Note: Clinical stage should be assigned before the start of neoadjuvant therapy. |

Progression of disease | If there is documented progression of cancer before therapy or surgery, only information obtained before the documented progression is used for clinical and pathological staging. Progression does not include growth during the time needed for the diagnostic workup, but rather a major change in clinical status. Determination of progression is based on managing physician judgment, and may result in a major change in the treatment plan. |

Uncertainty among T, N, or M categories, and/or stage groups: rules for clinical decision making | If uncertainty exists regarding how to assign a category, subcategory, or stage group, the lower of the two possible categories, subcategories, or groups is assigned for - T, N, or M

- prognostic stage group/stage group

Stage groups are for patient care and prognosis based on data. Physicians may need to make treatment decisions if staging information is uncertain or unclear. Note: Unknown or missing information for T, N, M or stage group is never assigned the lower category, subcategory, or group. |

Uncertainty rules do not apply to cancer registry data | If information is not available to the cancer registrar for documentation of a subcategory, the main (umbrella) category should be assigned (e.g., T1 for a breast cancer described as < 2 cm in place of T1a, T1b, or T1c). If the specific information to assign the stage group is not available to the cancer registrar (including subcategories or missing prognostic factor categories), the stage group should not be assigned but should be documented as unknown. |

Prognostic factor category information is unavailable | If a required prognostic factor category is unavailable, the category used to assign the stage group is: - X, or

- If the prognostic factor is unavailable, default to assigning the anatomic stage using clinical judgment.

|

Grade | The recommended histologic grading system for each disease site and/or cancer type, if applicable, is specified in each disease site and should be used by the pathologist to assign grade. The cancer registrar will document grade for a specific site according to the coding structure in the relevant disease site. |

Synchronous primary tumors in a single organ: (m) suffix | If multiple tumors of the same histology are present in one organ: - the tumor with the highest T category is classified and staged, and

- the (m) suffix is used

- An example of a preferred designation is: pT3(m) N0 M0.

- If the number of synchronous tumors is important, an acceptable alternative designation is to specify the number of tumors. For example, pT3(4) N0 M0 indicates four synchronous primary tumors.

Note: The (m) suffix applies to multiple invasive cancers. It is not applicable for multiple foci of in situ cancer or for a mixed invasive and in situ cancer. |

Synchronous primary tumors in paired organs | Cancers occurring at the same time in each of paired organs are staged as separate cancers. Examples include breast, lung, and kidney. Exception: For tumors of the thyroid, liver, and ovary, multiplicity is a T-category criterion, thus multiple synchronous tumors are not staged independently. |

Metachronous primary tumors | Second or subsequent primary cancers occurring in the same organ or in different organs outside the staging window are staged independently and are known as metachronous primary tumors. Such cancers are not staged using the y prefix. |

Unknown primary or no evidence of primary tumor | If there is no evidence of a primary tumor, or the site of the primary tumor is unknown, staging may be based on the clinical suspicion of the organ site of the primary tumor, with the tumor categorized as T0. The rules for staging cancers categorized as T0 are specified in the relevant disease sites. Example: An axillary lymph node with an adenocarcinoma in a woman, suspected clinically to be from the breast, may be categorized as T0 N1 (or N2 or N3) M0 and assigned Stage II (or Stage III). Examples of exception: The T0 category is not used for head and neck squamous cancer sites, as such patients with an involved lymph node are staged as unknown primary cancers using the “Cervical Nodes and Unknown Primary Tumors of the Head and Neck” system (T0 remains a valid category for human papillomavirus [HPV]- and Epstein-Barr virus [EBV]-associated oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal cancers). |

Date of diagnosis | It is important to document the date of diagnosis, because this information is used for survival calculations and time periods for staging. The date of diagnosis is the date a physician determines the patient has cancer. It may be the date of a diagnostic biopsy or other microscopic confirmation or of clear evidence on imaging. This rule varies by disease site and shares similarities with the earlier discussion on microscopic confirmation. |

Stage Classifications

Stage classifications are determined according to the point in time of the patient's care in relation to diagnosis and treatment. The five stage classifications are clinical, pathological, posttherapy/post neoadjuvant therapy, recurrence/ retreatment, and autopsy.

| Classification | Designation | Details |

Clinical | cTNM or TNM | Criteria: used for all patients with cancer identified before treatment It is composed of diagnostic workup information, until first treatment, including: - clinical history and symptoms

- physical examination

- imaging

- endoscopy

- biopsy of the primary site

- biopsy or excision of a single regional node or sentinel nodes, or sampling of regional nodes, with clinical T

- biopsy of distant metastatic site

- surgical exploration without resection

- other relevant examinations

Note: Exceptions exist by site, such as complete excision of primary tumor for melanoma. |

Pathological | pTNM | Criteria: used for patients if surgery is the first definitive therapy It is composed of information from: - diagnostic workup from clinical staging combined with

- operative findings, and

- pathology review of resected surgical specimens

|

Posttherapy or post neoadjuvant therapy | ycTNM and ypTNM | For purposes of posttherapy or post neoadjuvant therapy, neoadjuvant therapy is defined as systemic and/or radiation therapy given before surgery; primary radiation and/or systemic therapy is treatment given as definitive therapy without surgery. yc The yc classification is used for staging after primary systemic and/or radiation therapy, or after neoadjuvant therapy and before planned surgery Criteria: First therapy is systemic and/or radiation therapy yp The yp classification is used for staging after neoadjuvant therapy and planned post neoadjuvant therapy surgery. Criteria: First therapy is systemic and/or radiation therapy and is followed by surgery. |

Recurrence or retreatment | rTNM | This classification is used for assigning stage at time of recurrence or progression until treatment is initiated. Criteria: Disease recurrence after disease-free interval or upon disease progression if further treatment is planned for a cancer that: - recurs after a disease-free interval or

- progresses (without a disease-free interval)

rc Clinical recurrence staging is assigned as rc. rp Pathological staging information is assigned as rp for the rTNM staging classification. This classification is recorded in addition to and does not replace the original previously assigned clinical (c), pathological (p), and/or posttherapy (yc, yp) stage classifications, and these previously documented classifications are not changed. |

Autopsy | aTNM | This classification is used for cancers not previously recognized that are found as an incidental finding at autopsy, and not suspected before death (i.e., this classification does not apply if an autopsy is performed in a patient with a previously diagnosed cancer). Criteria: No cancer suspected prior to death Both clinical and pathological staging information is used to assign aTNM. |

Note S: Identification of Primary Site(s)

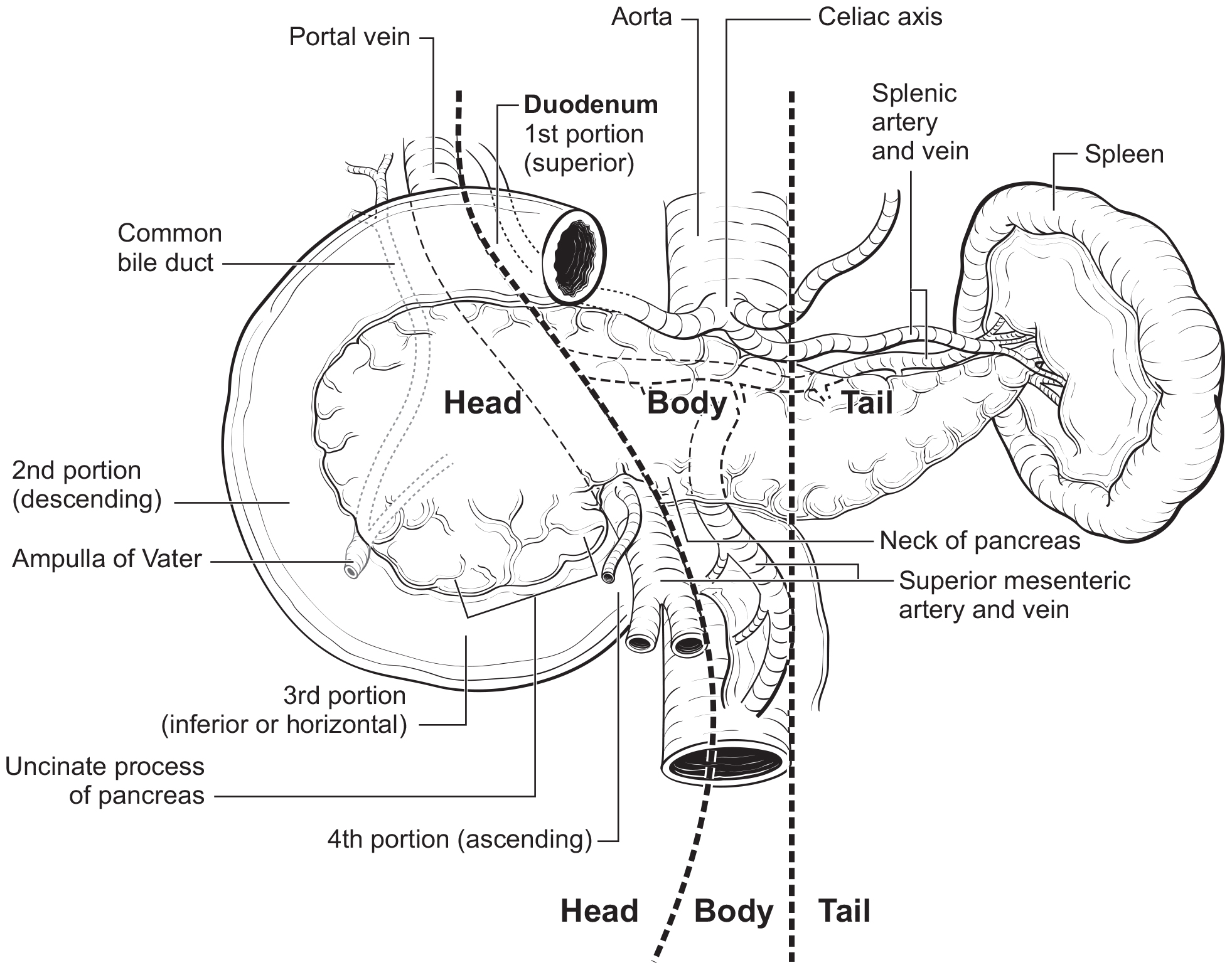

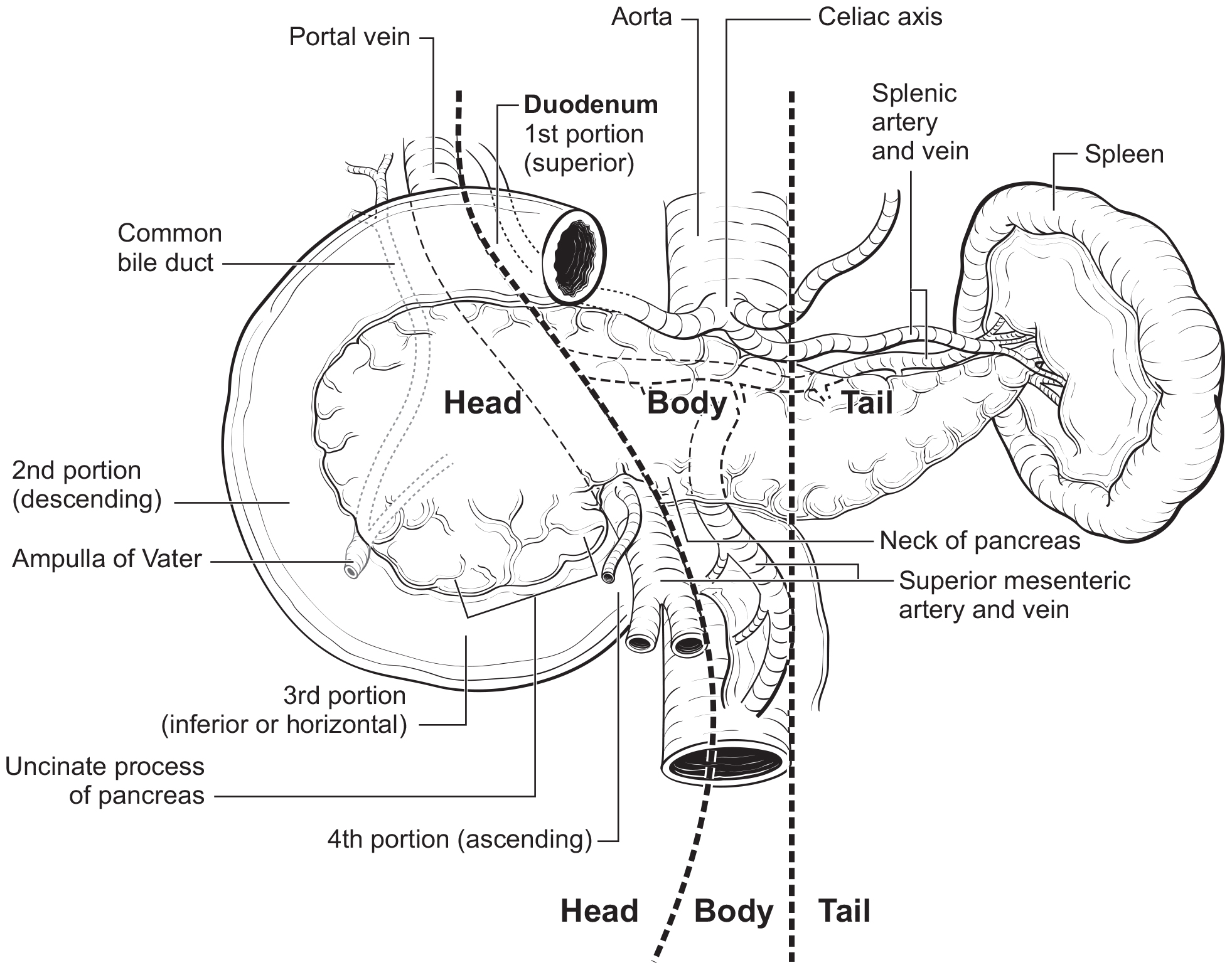

The pancreas is a long, coarsely lobulated gland that lies transversely across the posterior abdomen and extends from the duodenum to the splenic hilum. The organ is divided into a head with an uncinate process, a neck, a body, and a tail. These are contiguous regions without sharp anatomic distinctions. The pancreas neck lies anterior to the superior mesenteric vessels. The anterior aspect of the body of the pancreas is covered by peritoneum and is in contact with the posterior wall of the stomach; posteriorly, the pancreas extends within the retroperitoneal soft tissue to the inferior vena cava, superior mesenteric vein, splenic vein, and left adrenal and kidney. PanNETs are distributed throughout the pancreas. Tumors of the head of the pancreas are those arising to the right of the superior mesenteric-portal vein confluence (Figure NET Pancreas- Anatomy). The uncinate process is the part of the pancreatic head that extends behind the superior mesenteric vessels. The neck overlies the superior mesenteric vessels. Tumors of the body of the pancreas are defined as those arising to the left of the neck. Laterally to the left side, the body becomes the tail of the pancreas without any clear junction point.

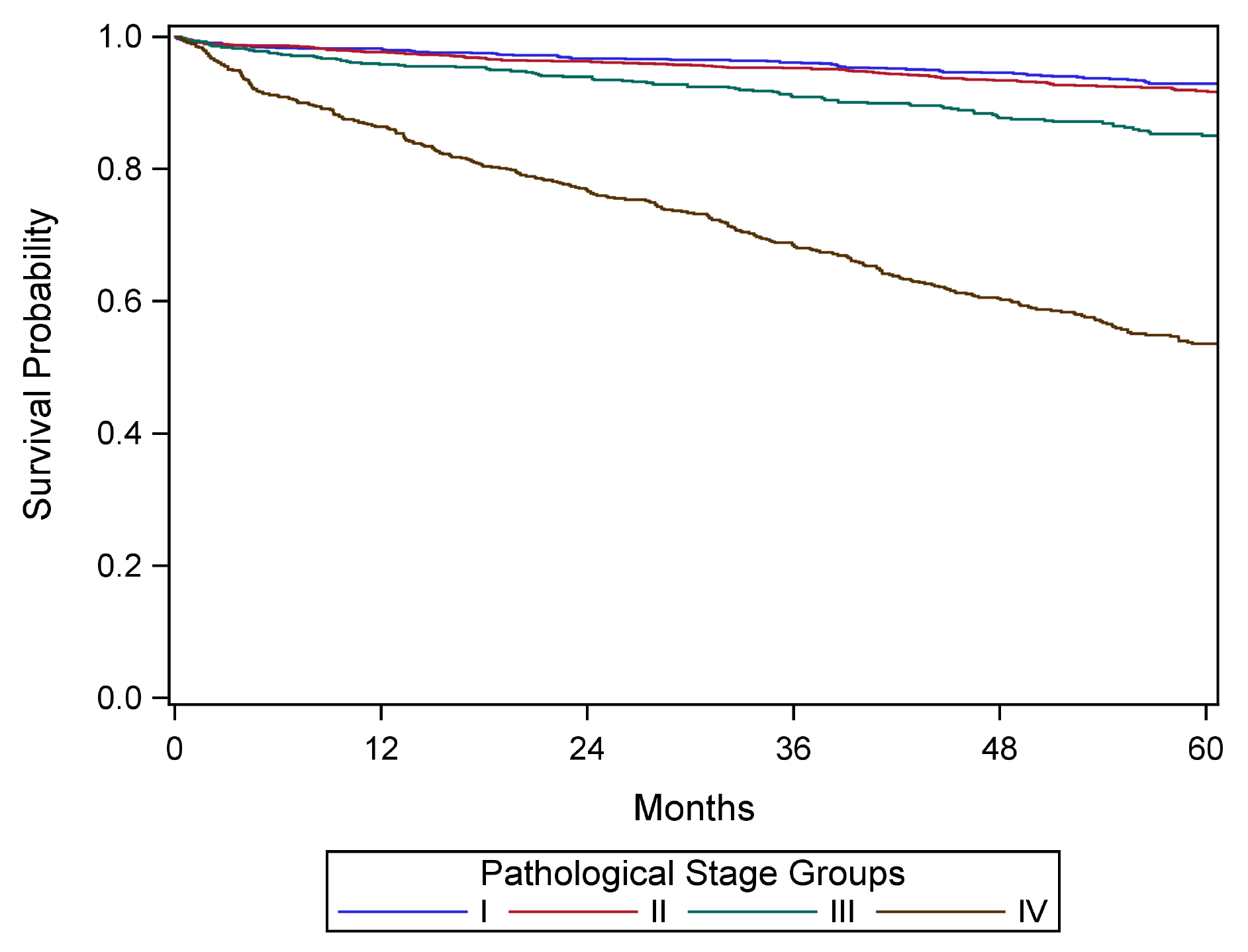

42.fig-AJCCFig52 FIGURE NET PANCREAS-ANATOMY. Anatomy of the pancreas. This protocol stages neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas.

The anatomy of the pancreas is described in Note S: Identification of Primary Site(s) with a figure of the anatomy.

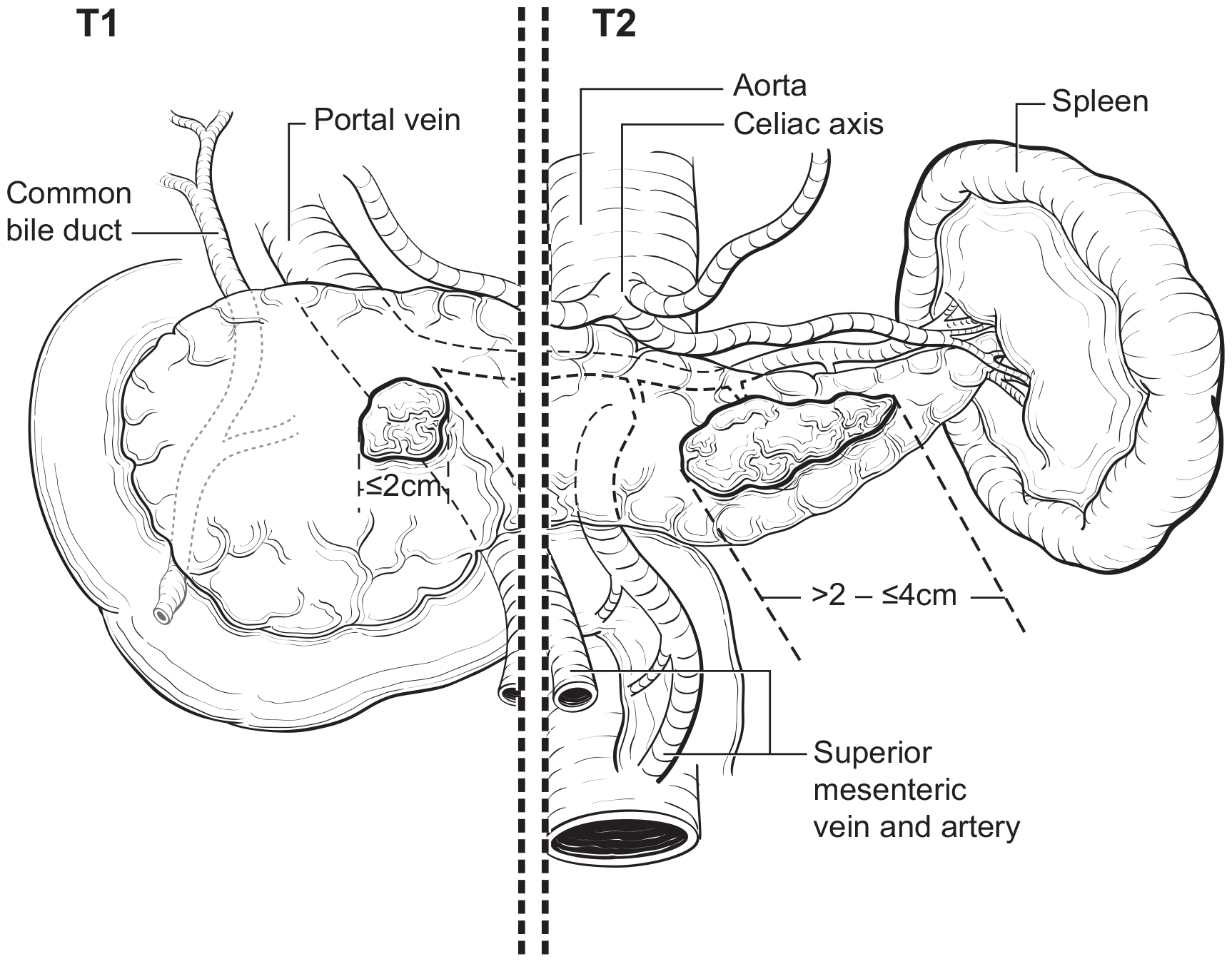

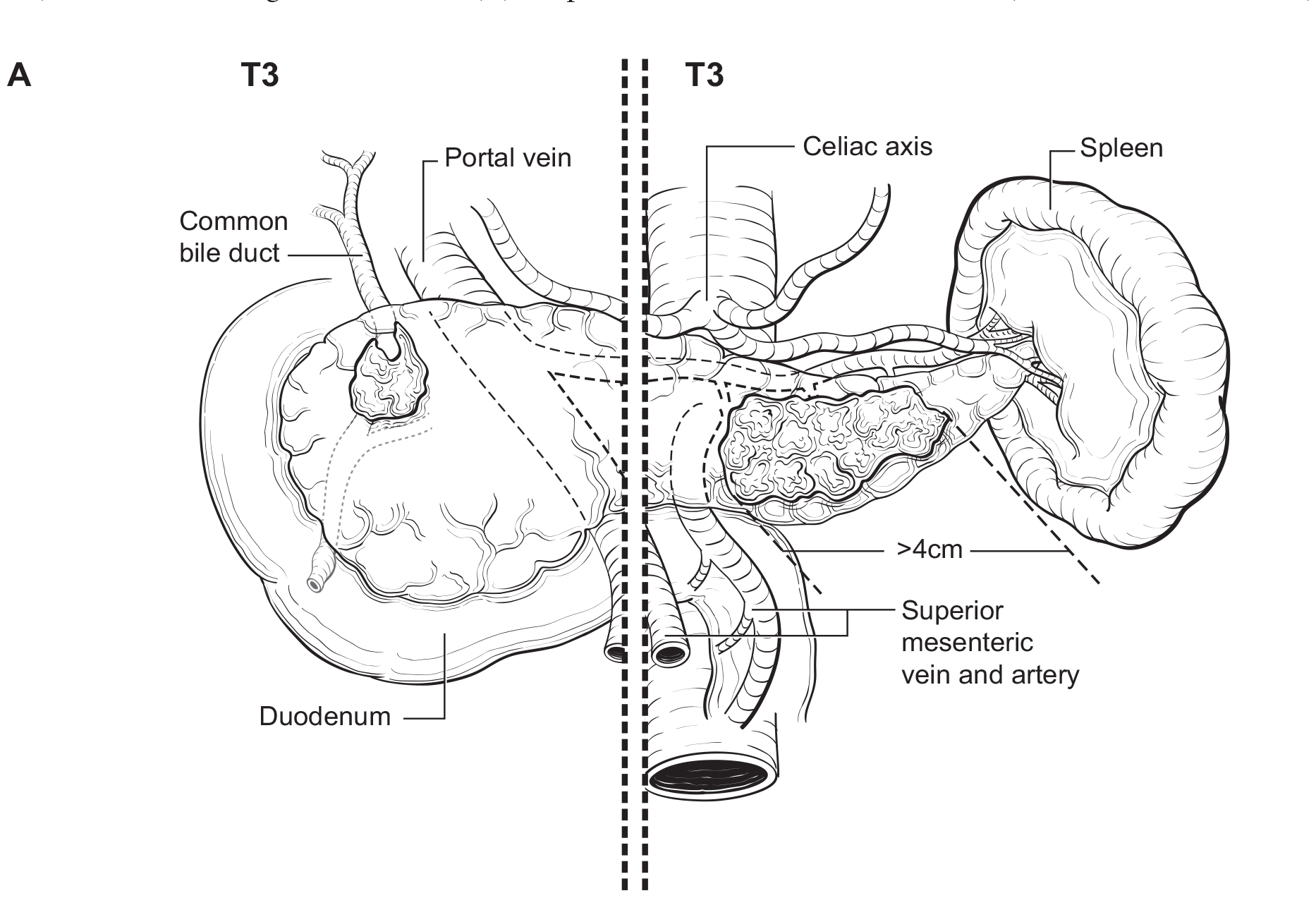

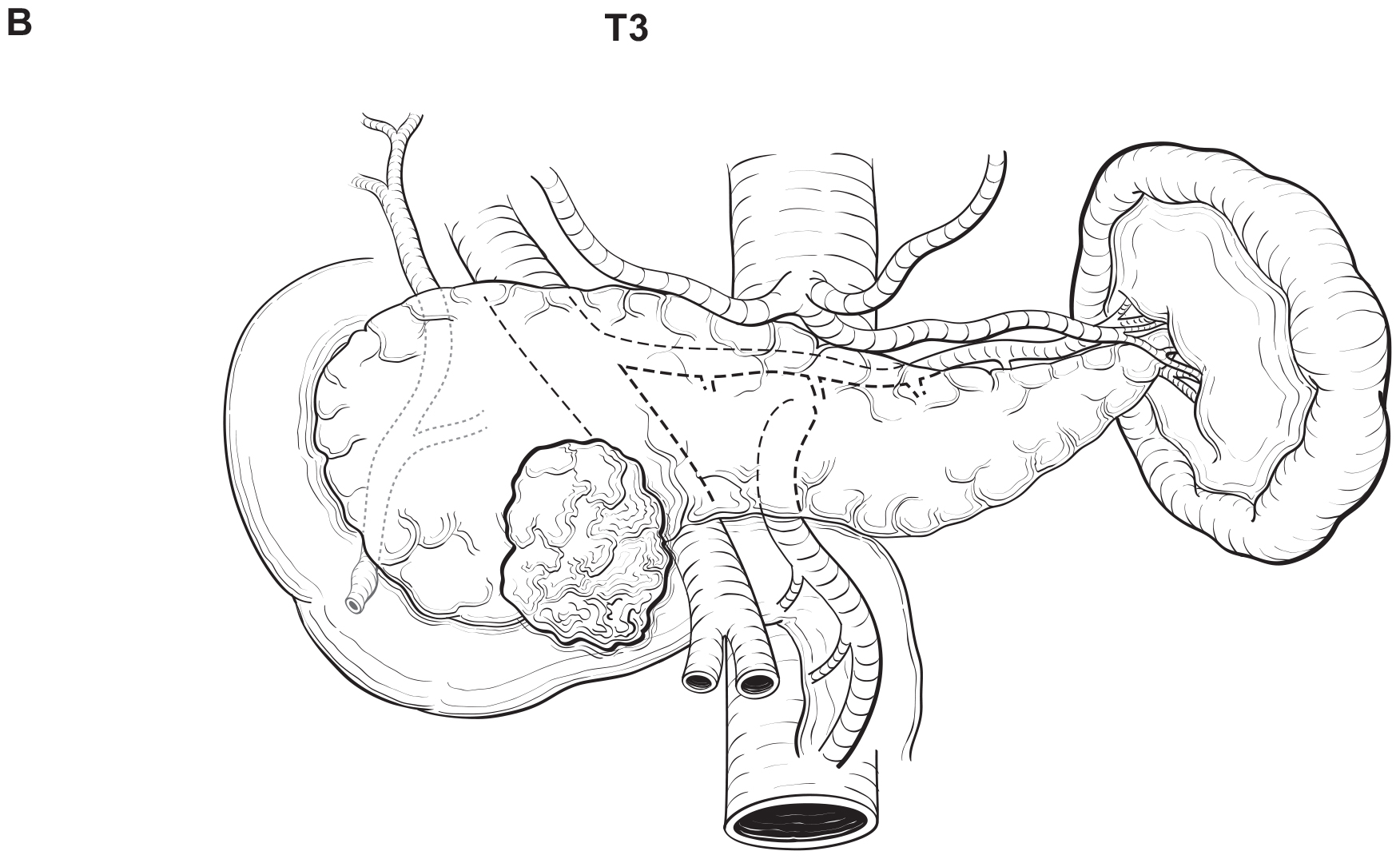

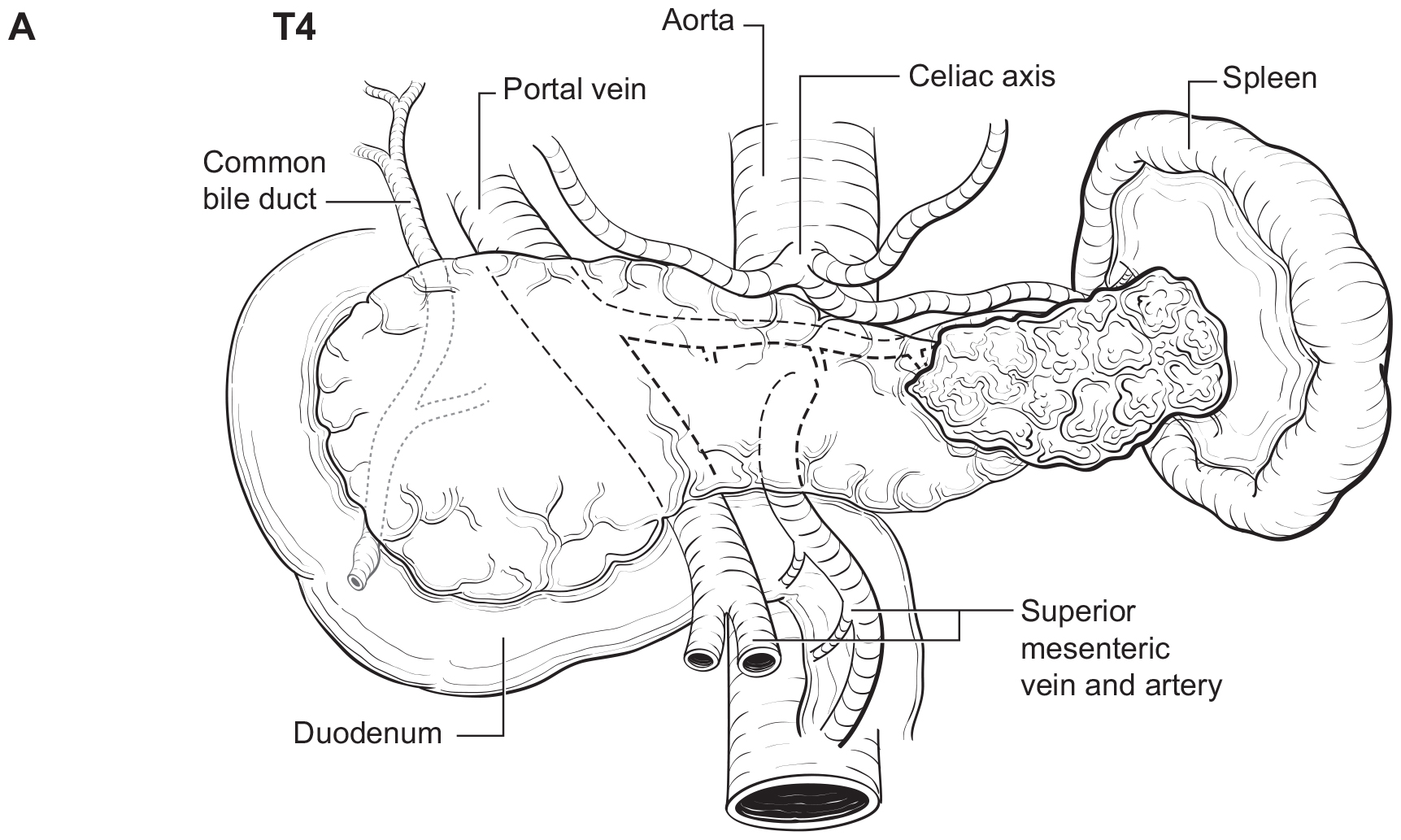

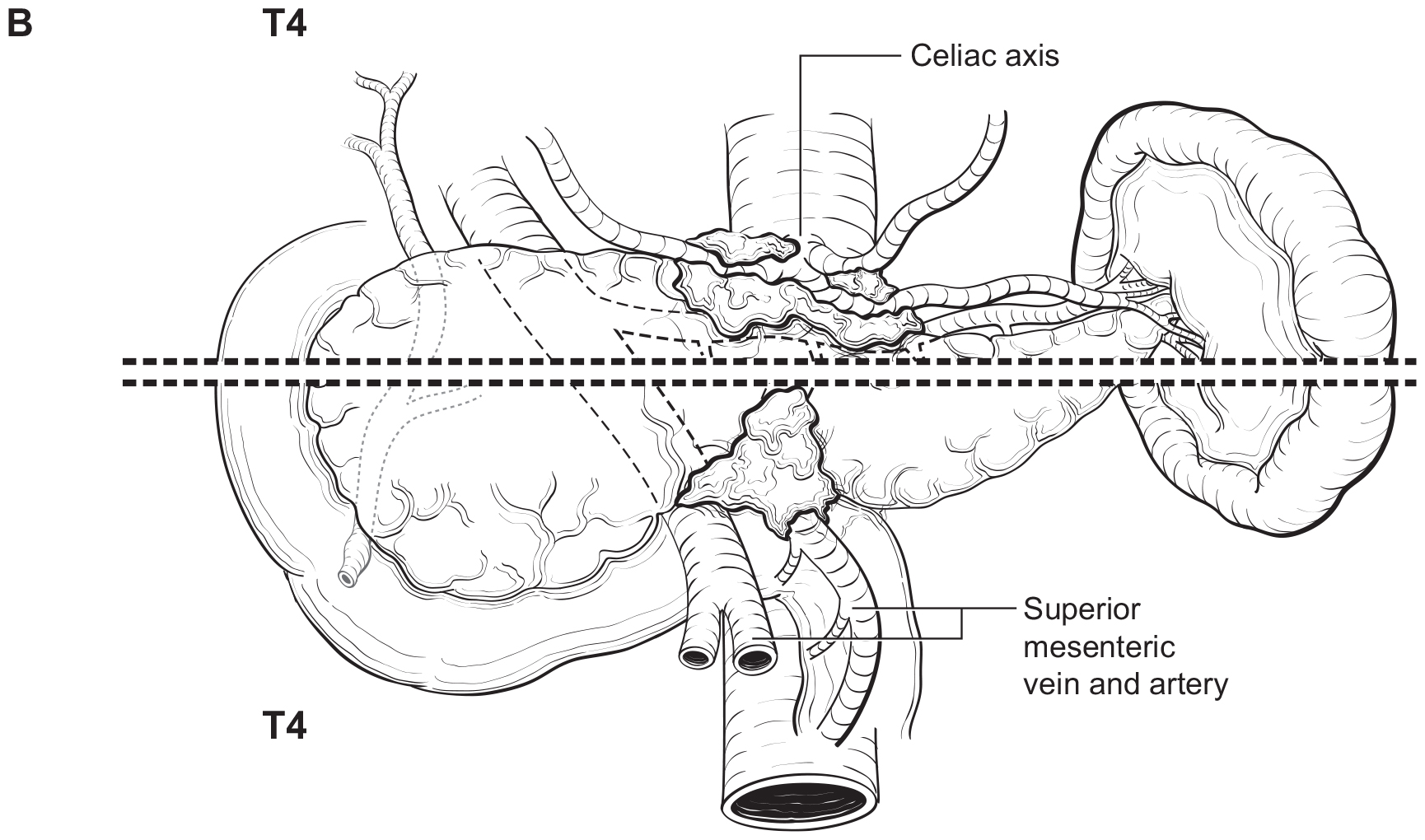

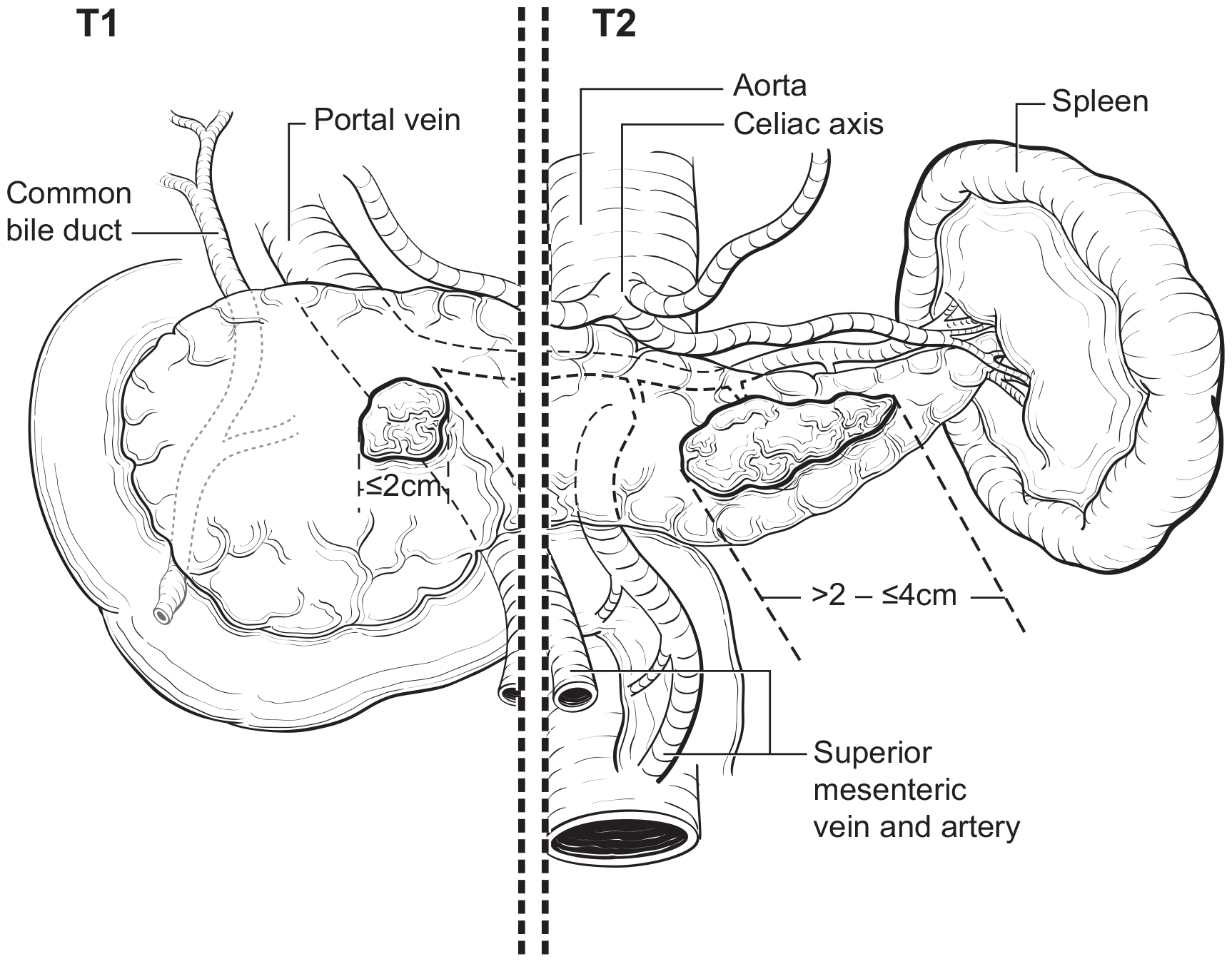

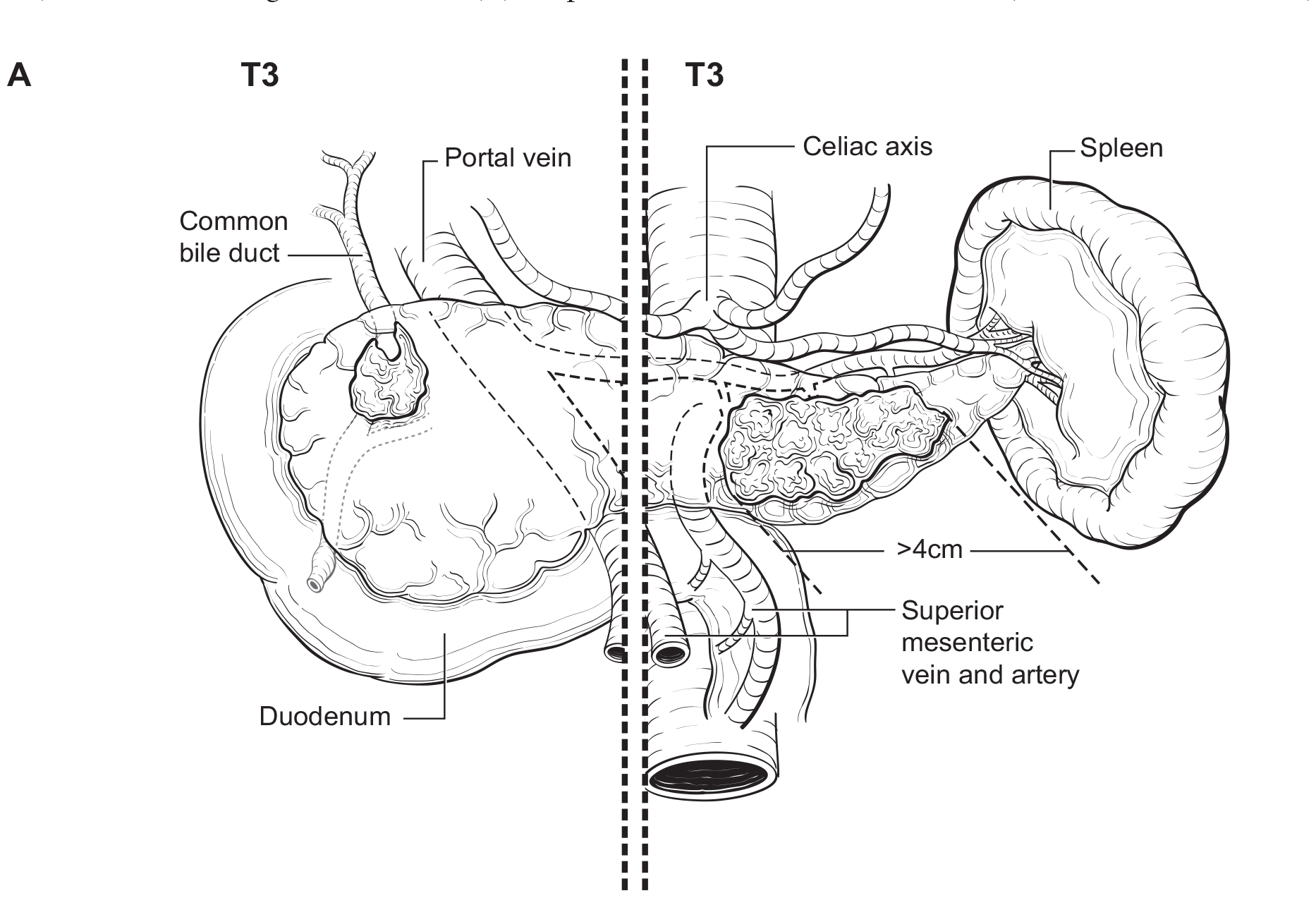

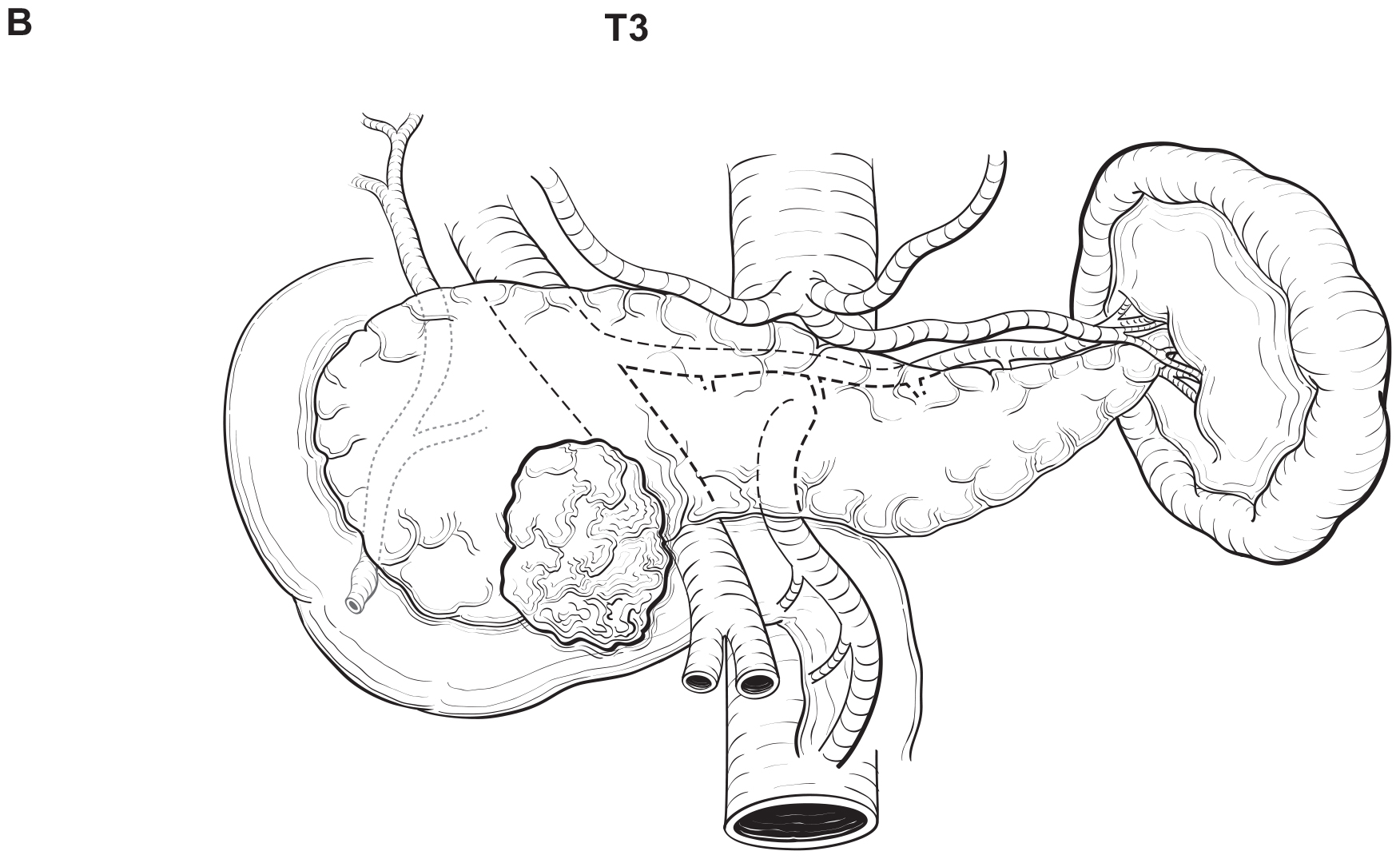

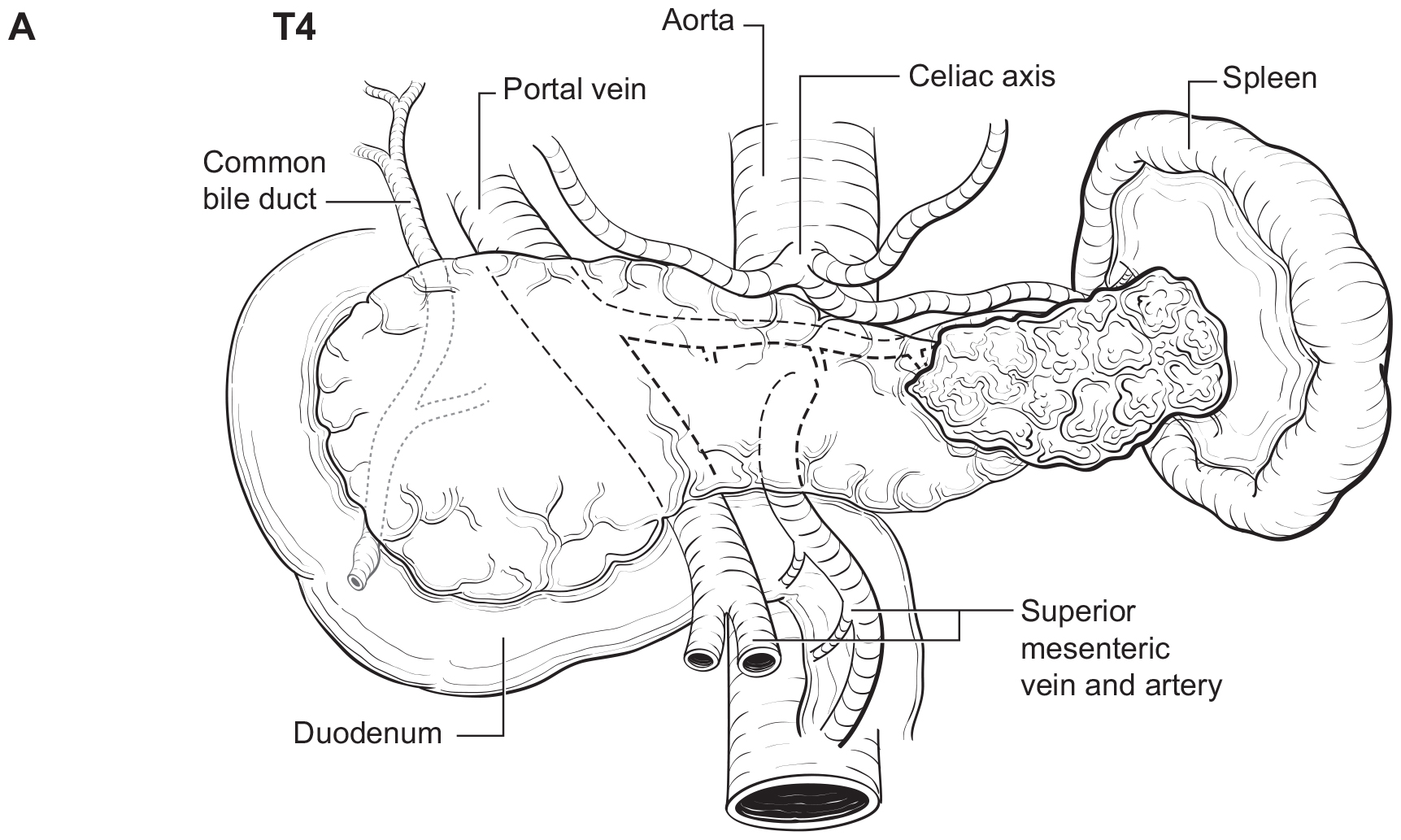

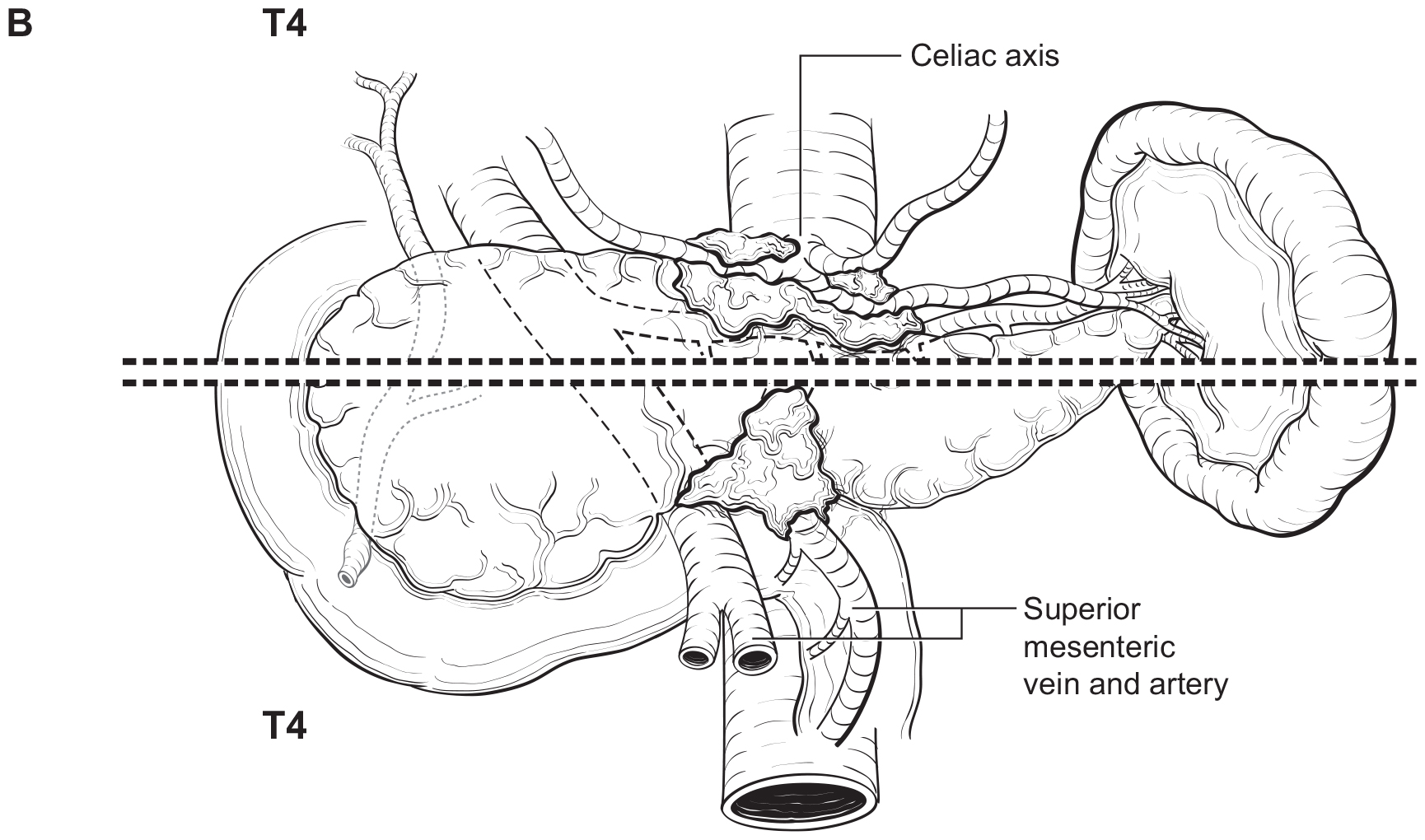

The T category definition entails recognizing the pancreas limits and tumor size for T1-T3 (Figure NET Pancreas-T1, T2 and Figure NET Pancreas-T3 (A-right side of line)). The invasion of the duodenal wall (Figure NET Pancreas-T3 (B)) including the ampulla or common bile duct (Figure NET Pancreas-T3 (A-left side of line) is T3. Invasion of nearby anatomical organs (stomach, spleen, colon, adrenal gland) or of the wall of large vessels (celiac axis, superior mesenteric artery/vein, common hepatic artery/vein, portal vein, splenic artery/vein and gastroduodenal artery/vein) is considered T4 (Figure NET Pancreas-T4).

Partial resection (pancreaticoduodenectomy or distal pancreatectomy) or total pancreatectomy, including the tumor and associated regional lymph nodes, provides the optimal information for pathological staging. In pancreaticoduodenectomy specimens, the bile duct, pancreatic duct, and superior mesenteric artery margins should be evaluated grossly and microscopically. The superior mesenteric artery margin also has been termed the retroperitoneal, vascular, or uncinate margin. In total pancreatectomy specimens, the bile duct and retroperitoneal margins should be assessed. Duodenal (with pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy) and gastric (with standard pancreaticoduodenectomy) margins rarely are involved, but their status should be included in the surgical pathology report. Reporting of margins may be facilitated by ensuring documentation of the pertinent margins: 1) common bile (hepatic) duct, 2) pancreatic neck, 3) superior mesenteric artery, 4) other soft tissue margins (i.e., posterior pancreatic, duodenum, and stomach).

42.1 FIGURE NET PANCREAS-T1, T2. T1 (left of dotted line) is defined as tumor limited to the pancreas ≤ 2 cm in greatest dimension. T2 (right of dotted line) is defined as tumor limited to the pancreas > 2 cm but ≤ 4 cm in greatest dimension.

42.1 FIGURE NET PANCREAS-T3. T3 is defined as tumor limited to the pancreas, > 4 cm in greatest dimension (A-right of the dotted line) or tumor invading the duodenum (B), ampulla of Vater or common bile duct (A-left of the dotted line).

42.1 FIGURE NET PANCREAS-T4. T4 is defined as tumor invading adjacent organs (stomach, spleen, colon, adrenal gland) (A) or the wall of large vessels (celiac axis, superior mesenteric artery/vein, splenic artery/vein, gastroduodenal artery/ vein, portal vein) (B).

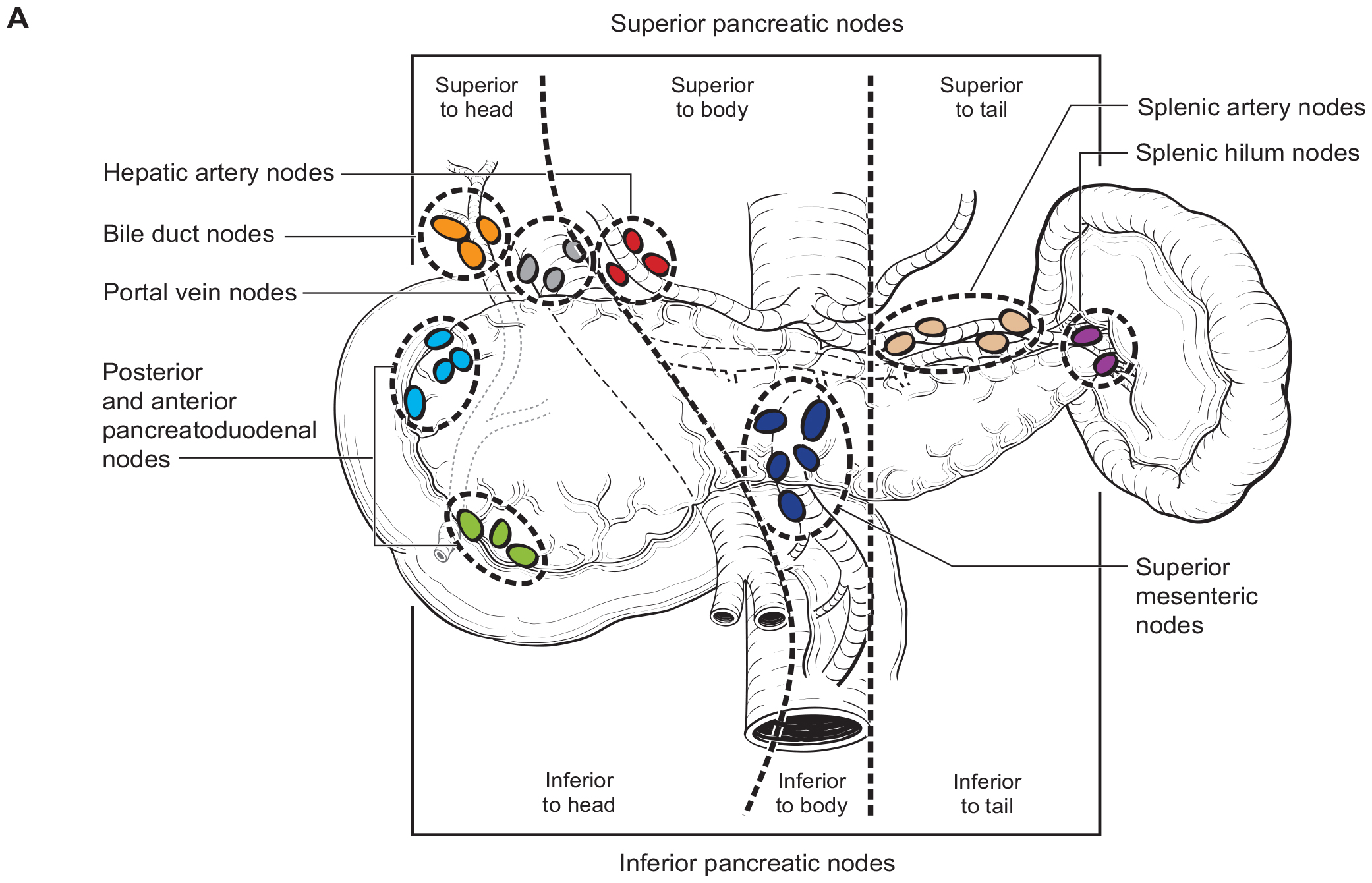

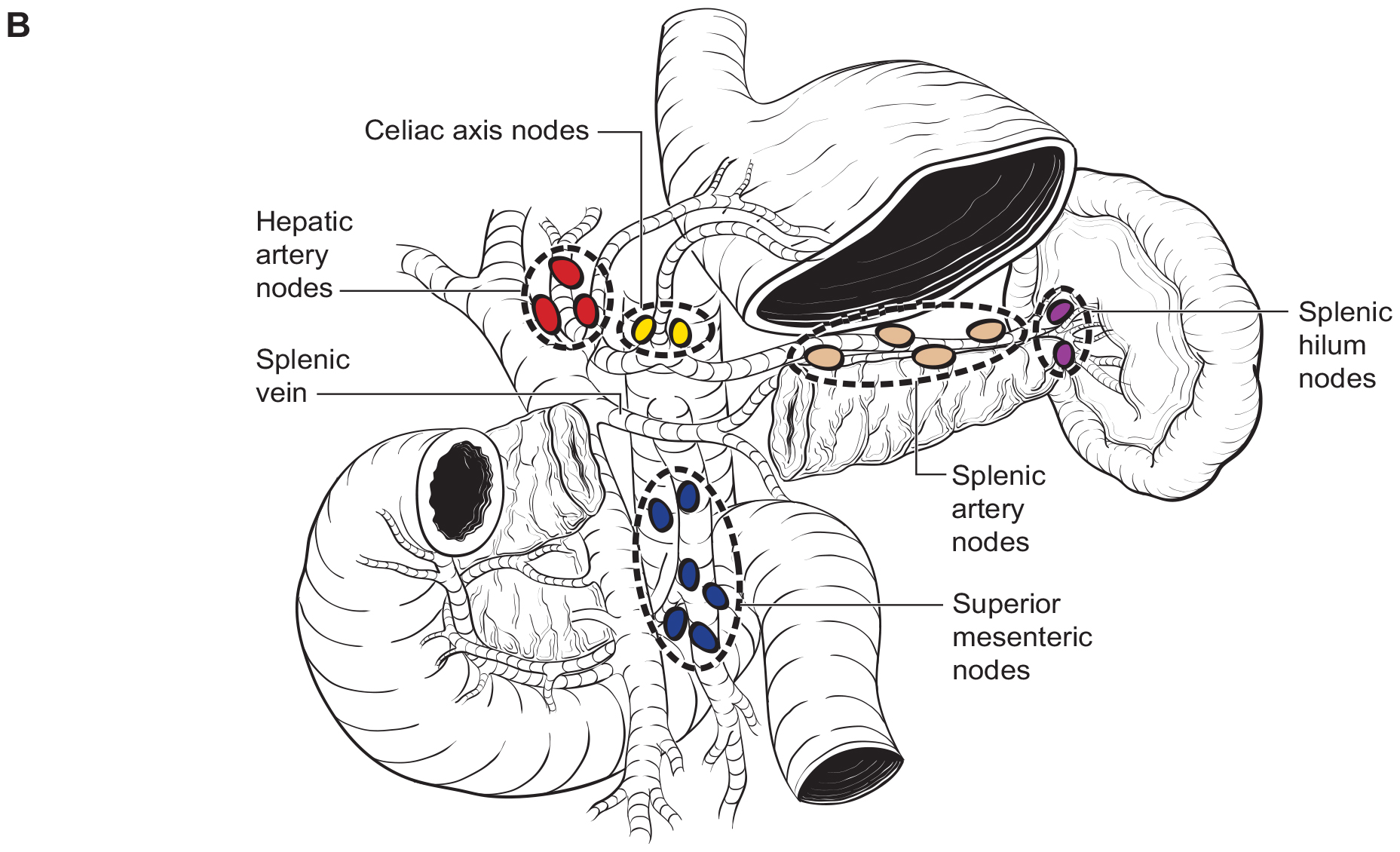

Regional Lymph Nodes

A rich lymphatic network surrounds the pancreas, and accurate tumor staging requires analysis of regional lymph nodes. Optimal histologic examination of a pancreaticoduodenectomy specimen should include analysis of 11-15 lymph nodes.31 For left sided tumors, en-bloc splenectomy may facilitate margin clearance and adequate lymph node retrieval. For patients with PanNETs at low risk for malignant behavior (i.e. low risk sporadic tumors, or insulinoma) the need for splenectomy should be balanced against the benefit of splenic preservation. Similarly, parenchymal sparing procedures such as central pancreatectomy or enucleation may be considered in highly selected low risk cases; the lymph node yield in these cases may be limited.

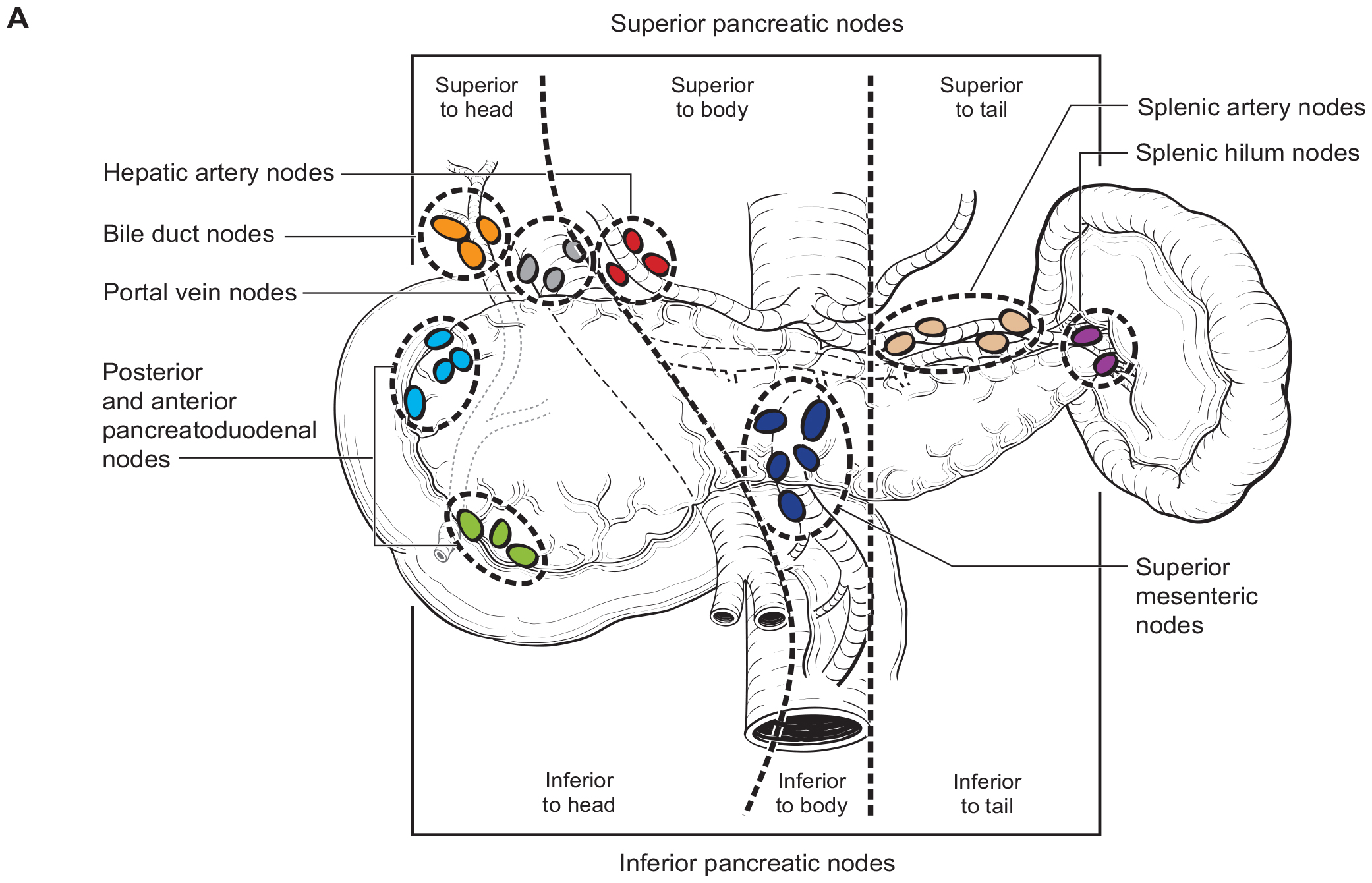

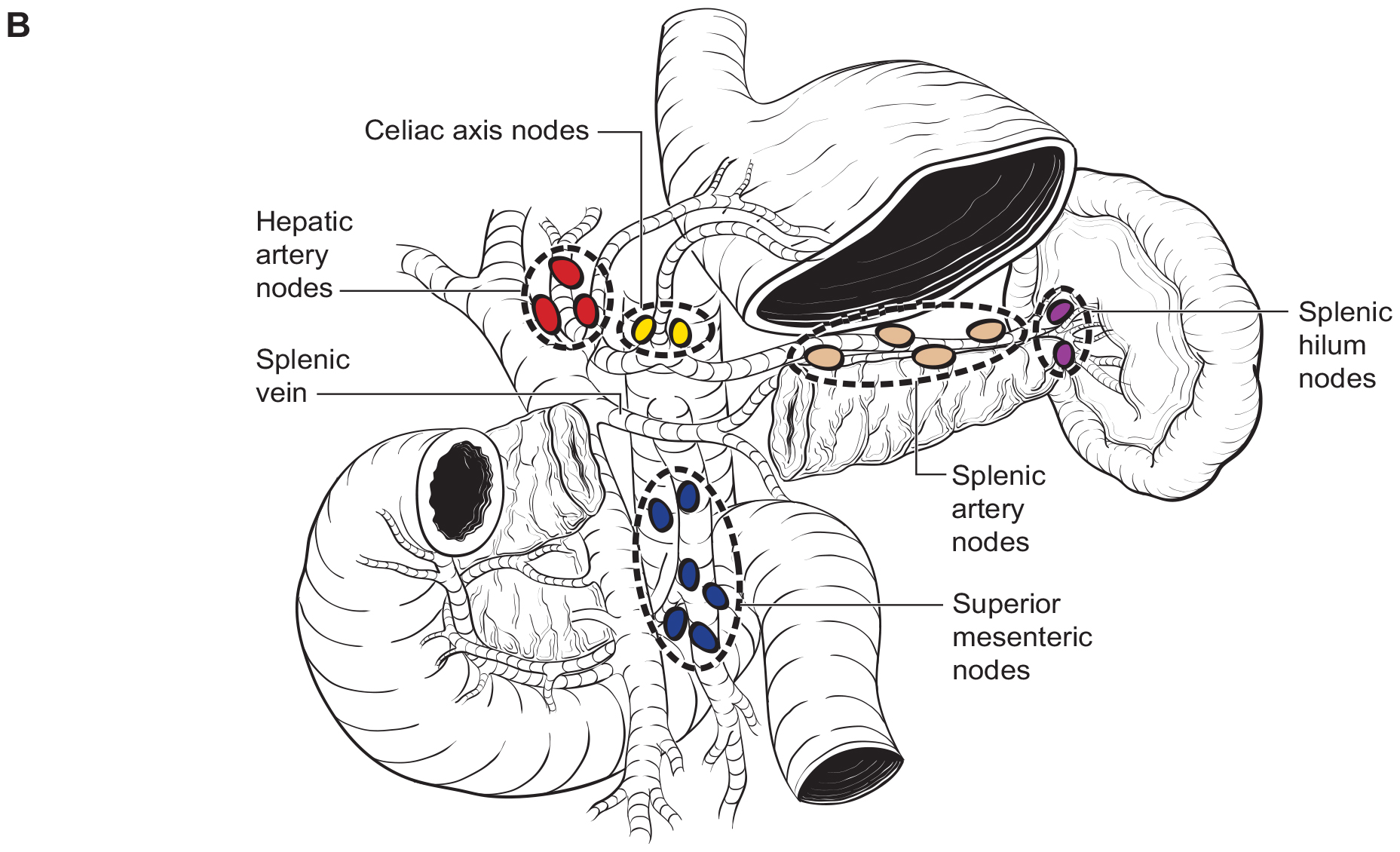

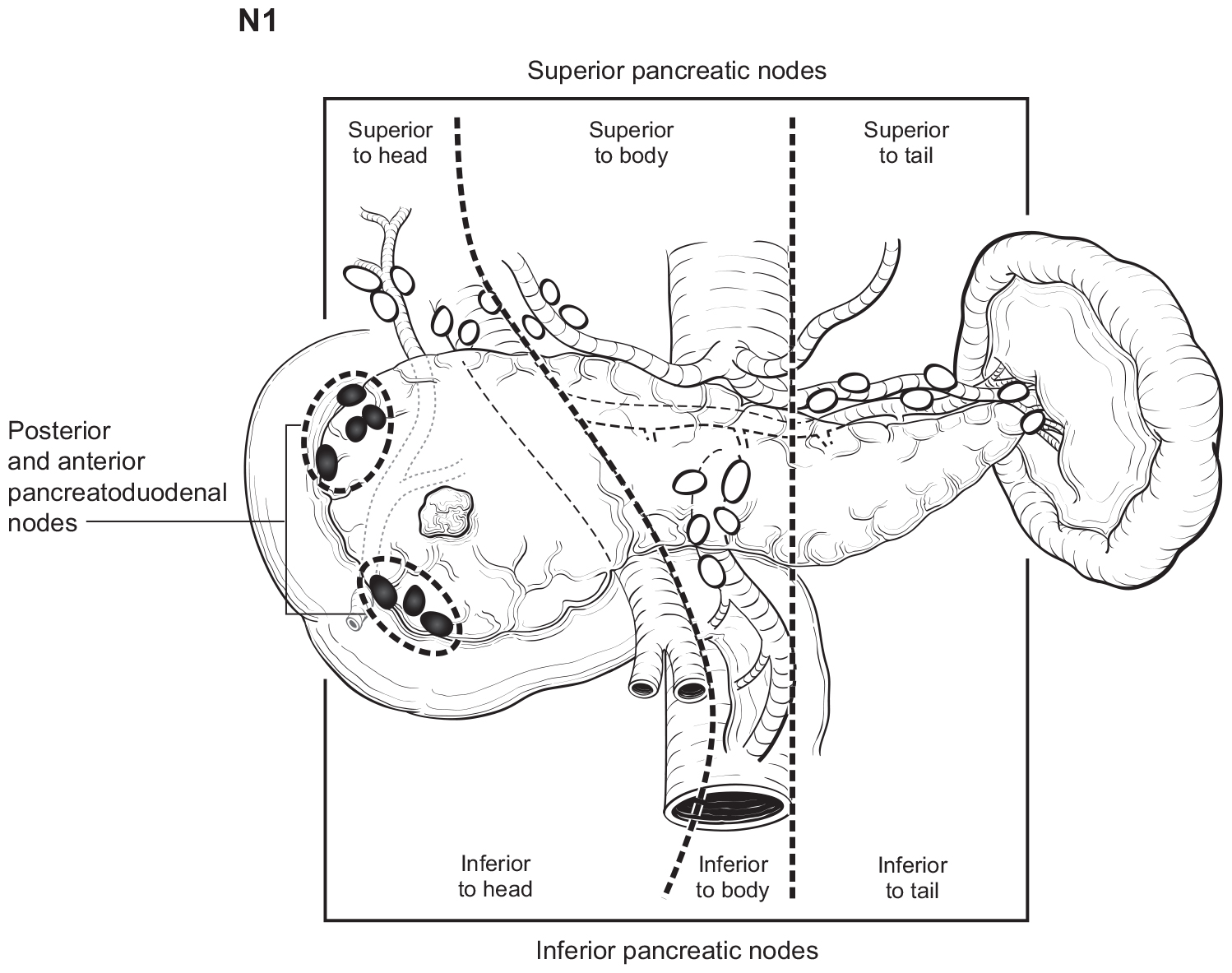

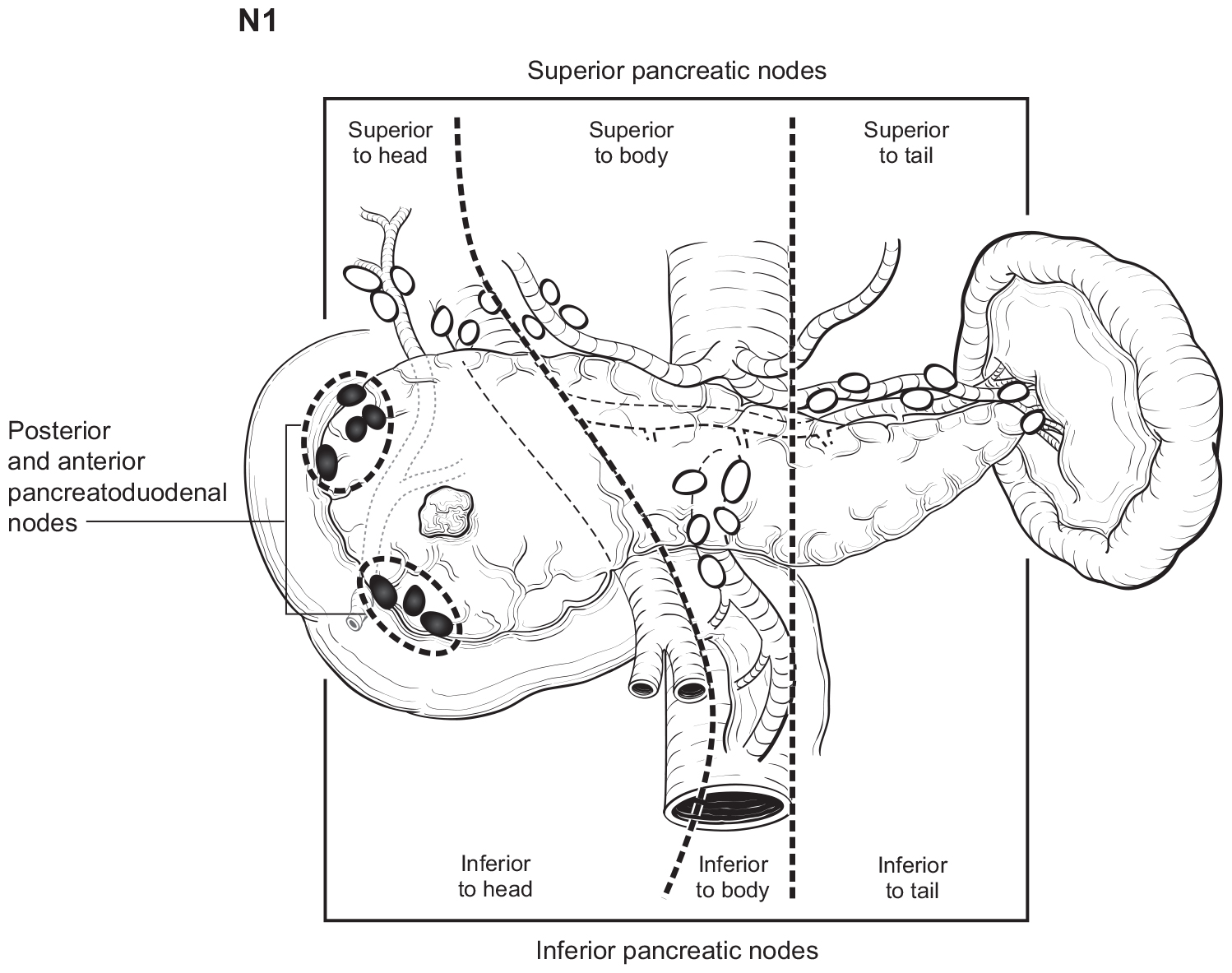

The number of lymph nodes examined and the number of positive lymph nodes should be specified in the pathology report. Anatomic division of regional lymph nodes is not necessary; however, separately submitted lymph nodes should be reported as labeled by the surgeon. An N category (N0 or N1) should be assigned as long as at least one lymph node has been assessed, even if the optimal number of lymph nodes have not been examined. NX should be applied only if no lymph nodes were assessed (e.g., if enucleation was performed). Positive peritoneal cytology is considered M1. The standard regional lymph node basins and soft tissues resected for tumors located in the head and neck of the pancreas include lymph nodes along the common bile duct, common hepatic artery, portal vein, posterior and anterior pancreatoduodenal arcades, and the superior mesenteric vein and right lateral wall of the superior mesenteric artery (Figure NET Pancreas- Nodal Map-A). For cancers located in the body and tail, regional lymph node basins include lymph nodes along the common hepatic artery, celiac axis, splenic artery, and splenic hilum (Figure NET Pancreas- Nodal Map-B). Involvement of peripancreatic lymph nodes is considered regional disease and classified as N1 (Figure NET Pancreas- N1).

42.1 FIGURE NET PANCREAS-NODAL MAP. Regional lymph nodes for Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Pancreas.

42.1 FIGURE NET PANCREAS-N1. N1 is defined as tumor involvement of regional lymph node(s).

Additional data elements that are clinically significant but not required for staging are identified with a dagger symbol.(†)