All newly diagnosed patients with malignant lymphomas should have formal documentation of the anatomic disease extent before the initial therapeutic intervention; that is, clinical stage must be assigned and recorded. Although patients with recurrent disease generally do not have a new clinical stage assigned at the time of relapse, some prognostic models include stage at the time of second-line therapy, particularly in Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), with intent to proceed with high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell rescue.5-8 In all cases, recording of the anatomic disease extent at the time of relapse is recommended.

Lugano Classification Modification of the Ann Arbor Staging System

Anatomic staging of lymphomas traditionally has been based on the Ann Arbor classification system, which was originally developed more than 30 years ago for HL. It was based on the relatively predictable pattern of spread of HL and improved the ability to determine which patients might be suitable candidates for radiation therapy.2 It was updated as the “Cotswold system” to address some of the issues present in the original staging system and to accommodate newer diagnostic techniques, including computed tomography (CT) scan.1 It subsequently was applied to non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) as well, despite the fact that the pattern of spread is less predictable than that of HL. The Ann Arbor classification has been accepted as the best means of describing the anatomic disease extent and has been useful as a universal system for a variety of lymphomas; therefore, it was adopted by the AJCC and the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) as the official system for classifying the anatomic extent of disease in HL and NHL, with the exception of cutaneous lymphomas (e.g., mycosis fungoides), which are discussed later in this chapter. However, advances in diagnostics and therapy provided the impetus to review and modernize the evaluation and staging of lymphoma. Workshops were held at the 11th and 12th International Conference on Malignant Lymphoma to study areas in need of clarification or updating and then to review the proposed changes. The Lugano classification was published and forms the basis for revised recommendations regarding anatomic staging and evaluation of disease before and after therapy.4 This staging system is adopted by the AJCC.

For the purposes of coding and staging, lymph nodes, Waldeyer's ring, thymus, and spleen are considered nodal or lymphatic sites. Extranodal or extralymphatic sites include the adrenal glands, blood, bone, bone marrow, central nervous system (CNS; leptomeningeal and parenchymal brain disease), gastrointestinal (GI) tract, gonads, kidneys, liver, lungs, skin, ocular adnexae (conjunctiva, lacrimal glands, and orbital soft tissue), skin, uterus, and others. HL rarely presents in an extranodal site alone, but about 25% of NHLs are extranodal at presentation. The frequency of extranodal presentation varies dramatically among different lymphomas, however, with some (e.g., mycosis fungoides and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue [MALT] lymphomas) being virtually always extranodal, except in advanced stages of the diseases, and some (e.g., follicular lymphoma) seldom being extranodal, except for bone marrow involvement.

The Lugano classification includes an E suffix for lymphomas with either localized extralymphatic presentation (Stage IE) or by contiguous spread from nodal disease (Stage IIE). For example, lymphoma presenting in the thyroid gland with cervical lymph node involvement should be staged as IIE. However, in a change from the Cotswold modification of the Ann Arbor staging system, E lesions do not apply to patients with Stage III nodal disease; any patient with nodal disease above and below the diaphragm with concurrent contiguous extralymphatic involvement is Stage IV (previously Stage IIIE). Frequently, extensive lymph node involvement is associated with extranodal extension of disease that also may directly invade other organs. Such extension should be described with the E suffix if the nodal disease is on one side of the diaphragm. For example, mediastinal lymph nodes with adjacent lung extension should be classified as Stage IIE disease. Other examples of Stage IIE diseases include extension into the anterior chest wall and into the pericardium from a large mediastinal mass (two areas of extralymphatic involvement) and no nodal involvement below the diaphragm; involvement of the iliac bone in the presence of adjacent iliac lymph node involvement and no nodal involvement above the diaphragm; involvement of a lumbar vertebral body in conjunction with para-aortic lymph node involvement and no nodal involvement above the diaphragm; and involvement of the pleura or chest wall as an extension from adjacent internal mammary nodes. A pleural or pericardial effusion with negative (or unknown) cytology is not an E lesion. Liver involvement is an exception; any liver involvement by contiguous or noncontiguous spread should be recorded as Stage IV.

The definition of disease bulk varies according to lymphoma histology. In HL, the extent of mediastinal disease is defined as the ratio between the maximum diameter of the mediastinal mass and maximal intrathoracic diameter based on CT imaging in the Lugano classification. In HL, bulk at other sites is defined as a mass >10 cm. A recent analysis has suggested that in early stage disease, masses > 7 cm (at any site) may dictate the inclusion of radiation to provide optimal outcomes.9 For NHL, the recommended definitions of bulk vary by lymphoma subtype. In follicular lymphoma, 6 cm has been suggested based on the Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index, version 2 (FLIPI-2) and its validation.10,11 In DLBCL, cutoffs ranging from 5 to 10 cm have been used, although 10 cm is recommended.12

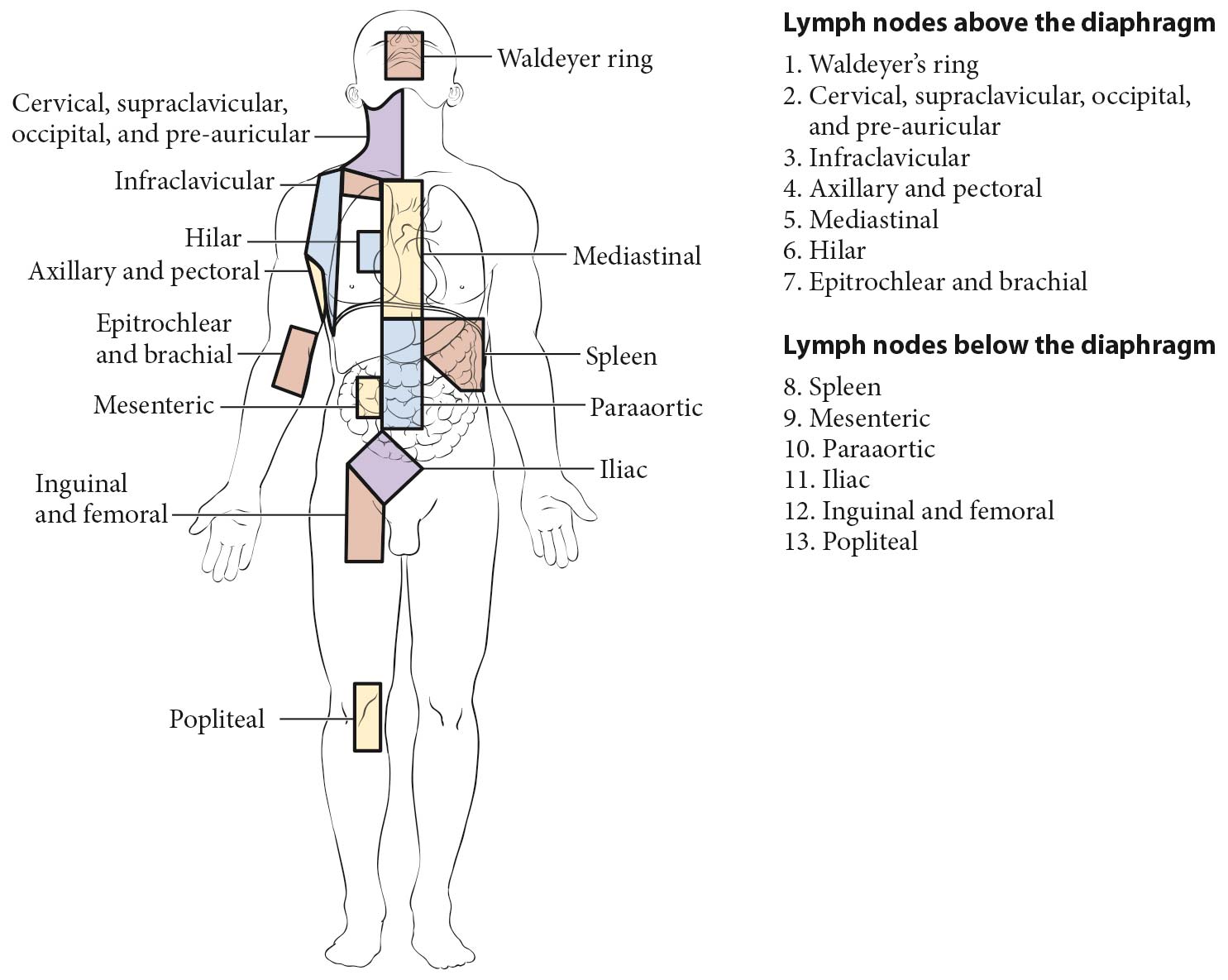

Lymph Node Regions

The staging classification for lymphoma uses the term lymph node region. The lymph node regions were defined at the Rye Symposium in 1965 and have been used in the Ann Arbor classification; this is unchanged in the Lugano classification (Figure 103.1). They are not based on any physiologic principles but rather have been agreed upon by convention. The currently accepted classification of core nodal regions is as follows:

- Right cervical nodes (including cervical, supraclavicular, occipital, and preauricular lymph nodes)

- Left cervical nodes

- Right axillary nodes

- Left axillary nodes

- Right infraclavicular nodes

- Left infraclavicular lymph nodes

- Mediastinal lymph nodes

- Right hilar lymph nodes

- Left hilar lymph nodes

- Para-aortic lymph nodes

- Mesenteric lymph nodes

- Right pelvic lymph nodes

- Left pelvic lymph nodes

- Right inguinofemoral lymph nodes

- Left inguinofemoral lymph nodes

In addition to these core regions, HL and NHLs may involve epitrochlear lymph nodes, popliteal lymph nodes, internal mammary lymph nodes (considered mediastinal by convention), occipital lymph nodes, submental lymph nodes, preauricular lymph nodes (all considered cervical, Figure 103.1), and many other small nodal areas. Clinical prognostic models may include specific definitions of nodal regions. For example, in follicular lymphoma, the FLIPI-2 uses a different definition of nodal regions (see prognostic factors for follicular lymphoma). This is also the case in determination of favorable versus unfavorable early-stage HL as proposed by the German Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG) and the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC; see prognostic factors for HL).

A and B Classification (Symptoms)

For HL, each stage should be classified as either A or B according to the absence or presence of defined constitutional symptoms. The designation A or B is not included in the revised staging of NHL,4 although clinicians are encouraged to record the presence of these symptoms in the medical record. The symptoms are as follows:

- Fevers. Unexplained fever with temperature above 38°C

- Night sweats. Drenching sweats (e.g., those that require change of bedclothes)

- Weight loss. Unexplained weight loss of more than 10% of the usual body weight in the 6 months prior to diagnosis

Other symptoms, such as chills, pruritus, alcohol-induced pain, and fatigue, are not included in the A or B designation but are recorded in the medical record, as the reappearance of these symptoms may be a harbinger of recurrence.

Criteria for Organ Involvement

Lymph Node Involvement

Lymph node involvement is demonstrated by enlargement of a node detected clinically or by imaging when alternative pathology may reasonably be ruled out. Imaging criteria include demonstration of fludeoxyglucose (FDG) avidity on FDG positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) or unexplained node enlargement on CT. Suspicious nodes should always be biopsied if treatment decisions are based on their involvement, preferably with an excisional biopsy; fine-needle aspirations are strongly discouraged because of the potential for false negatives or misdiagnosis because of loss of lymph node architecture. Core needle biopsy may be able to provide adequate material for diagnosis, particularly of a secondary site.

Spleen Involvement

Spleen involvement is suggested by unequivocal palpable splenomegaly and demonstrated by radiologic confirmation (FDG-PET or CT). Positive findings on FDG-PET include diffuse uptake, a solitary mass, miliary lesions, or nodules and those on CT include enlargement of >13 cm in cranial-caudal dimension, a mass, or nodules that are neither cystic nor vascular.

Liver Involvement

Liver involvement is demonstrated on FDG-PET by diffuse uptake or mass lesions and on CT by nodules that are neither cystic nor vascular. Clinical enlargement alone, with or without abnormalities of liver function tests, is not adequate. Liver biopsy may be used to confirm the presence of liver involvement in a patient with abnormal liver function tests or when imaging assessment is equivocal, if treatment will be altered on the basis of those results.

Lung Involvement

Lung involvement is demonstrated by FDG-avid pulmonary nodules on FDG-PET and evidence of parenchymal involvement on CT in the absence of other likely causes, especially infection. Lung biopsy may be required to clarify equivocal cases.

Bone Involvement

Bone involvement is demonstrated in FDG-avid lymphoma by avid lesions on FDG-PET. It is quite common for FDG-PET to demonstrate more sites of bone involvement than CT imaging. A bone biopsy from an involved area of bone may be necessary for a precise diagnosis, if treatment decisions depend on the findings.

CNS Involvement

CNS involvement often is heralded by symptoms and is demonstrated by (a) a spinal intradural deposit or spinal cord or meningeal involvement, which may be diagnosed on the basis of the clinical history and findings supported by plain radiology, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination with flow cytometry, CT, and/or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging (spinal extradural deposits should be carefully assessed because they may be the result of soft tissue disease that represents extension from bone metastasis or disseminated disease) and (b) parenchymal brain disease demonstrated on CT and/or MR imaging, which may be confirmed by biopsy.

Bone Marrow Involvement

Bone marrow involvement is assessed by an aspiration and bone marrow biopsy. In HL, it is rare to have bone marrow involvement in the absence FDG-avid bone site. Therefore, if FDG-PET/CT is performed as part of the staging evaluation, routine bone marrow aspiration and biopsy is not required for staging of HL. In DLBCL, the presence of FDG-avid skeletal lesions precludes the need for a bone marrow aspiration and biopsy. However, the procedure generally should be done in the absence of FDG-avid bone disease because of the risk of identifying discordant bone marrow involvement by a small cell lymphoma. For the indolent B-cell lymphoma, bone marrow aspiration and biopsy remains the standard for evaluation; however, it may be deferred in patients who are candidates for initial observation. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and/or flow cytometry may be useful adjuncts to histologic interpretation to determine whether a lymphocytic infiltrate is malignant.