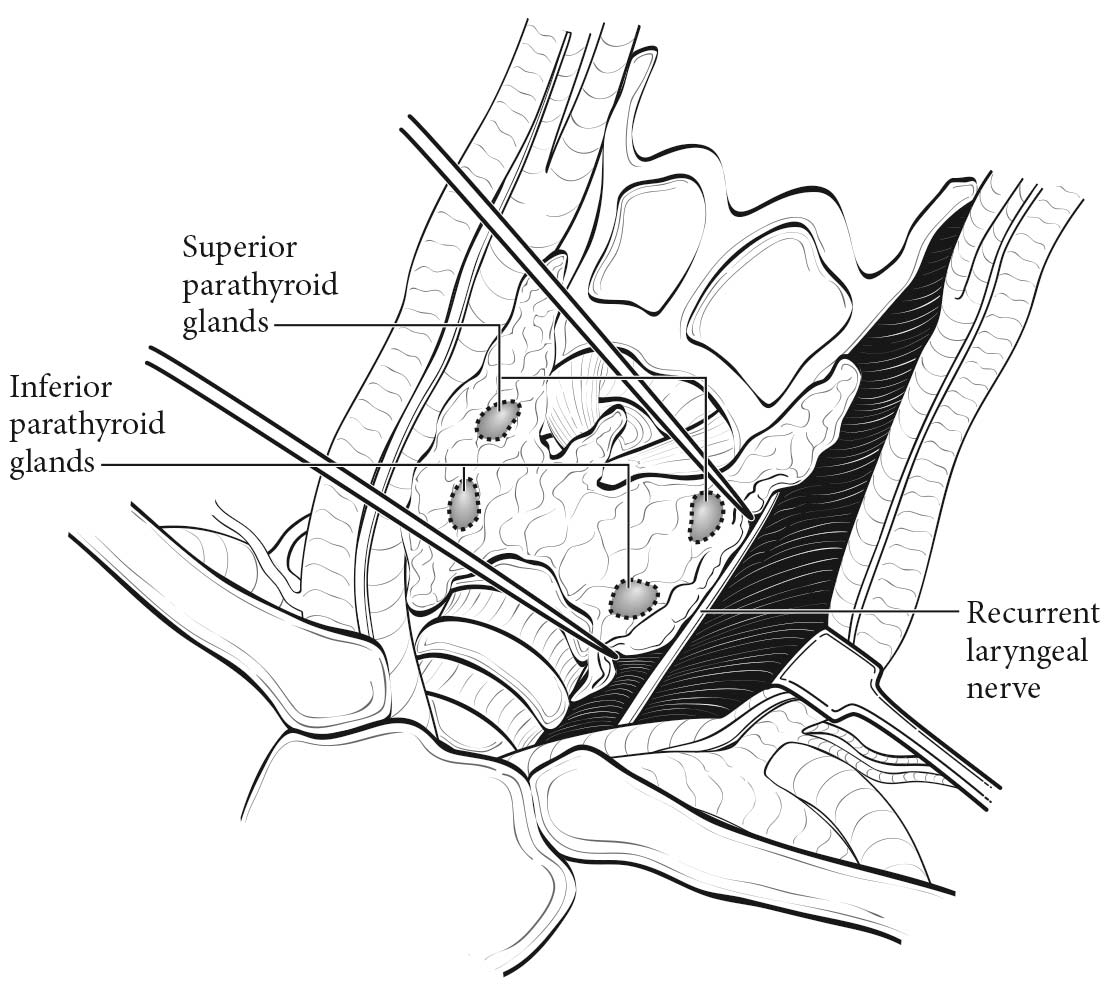

The parathyroid glands are composed of chief cells, oxyphil cells, and clear cells, and are usually located in the neck, adjacent to the thyroid gland. Because the parathyroid glands descend during embryologic development, the location of each gland varies. The superior parathyroid glands, derived from the fourth branchial pouch, descend with the thyroid gland, and are commonly located posterior to the upper third of the thyroid lobe.1 The inferior parathyroid glands descend with the thymus from the third branchial pouch, and may be located anywhere from the superior thyroidal poles to the anterior mediastinum.1,2 Parathyroid glands also may be located within the thyroid gland.3 Although the exact number of parathyroid glands varies among individuals, most people have two superior and two inferior parathyroid glands. (Figure 95.1)

The average weight of an individual gland is 30 to 50 mg.1,2 These glands are usually contained within a thin connective tissue capsule.1 If the capsule is absent, there may be nests of ectopic epithelial parathyroid cells mixed with fatty tissue near the gland.1

Parathyroid carcinoma develops within the parathyroid gland itself, and the location of the carcinoma is dependent on the embryologic descent and location of the affected gland.

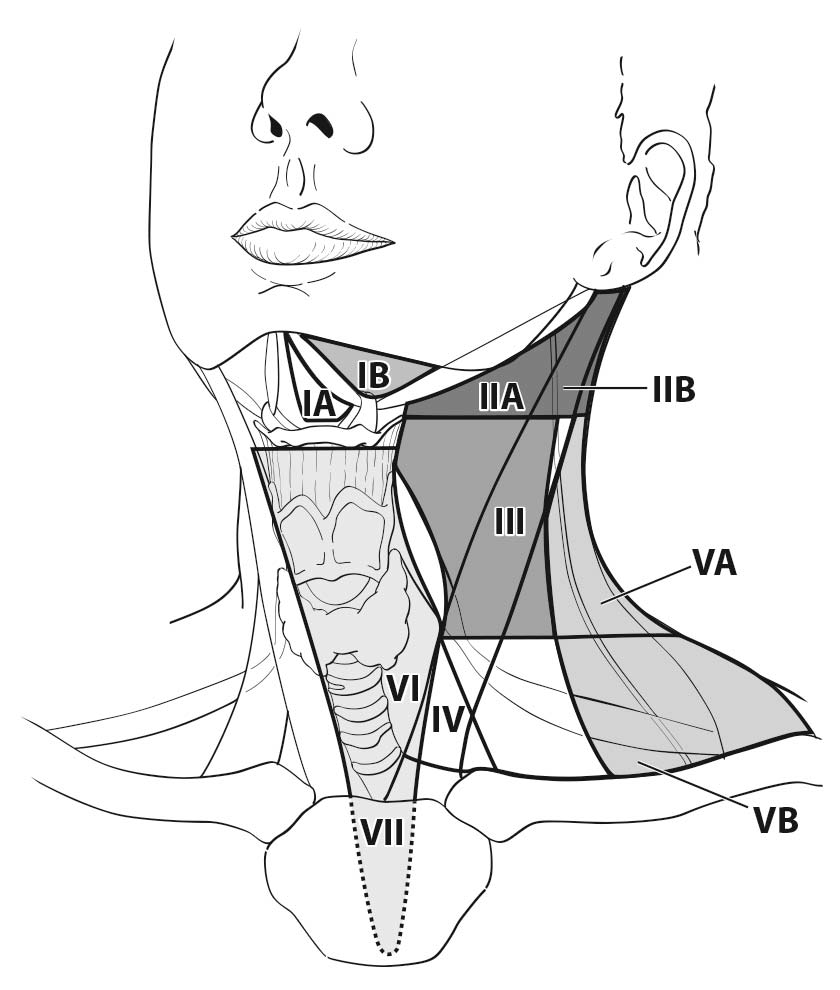

Parathyroid carcinoma has been shown to metastasize to locoregional lymph nodes. Occasionally, parathyroid cancer metastasizes to lymph nodes in the central compartment of the neck (level VI or VII) near the primary tumor.4 Rarely, parathyroid carcinoma metastasizes to lymph nodes in the lateral neck (levels II, III, IV, and V) (Figure 95.2).

Patients who present with a palpable neck mass, a serum calcium level greater than 14 mg/dL, and significantly elevated parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels should be suspected of harboring parathyroid carcinoma. Symptoms are similar to those in patients with severe primary hyperparathyroidism, including fatigue, cognitive deficits (difficulty with sleep, concentration, memory, multitasking, depression), bone/joint pain, fragility fractures, osteoporosis, pancreatitis, and kidney stones.5,6,8,10 Some patients with parathyroid carcinoma may develop weight loss and thromboembolic disease.2 Rarely, patients may present with neck pain.5 Some parathyroid carcinomas do not overproduce PTH, and these patients may be asymptomatic, with normal calcium levels.11

The diagnosis of parathyroid carcinoma should be considered in any patient with significantly elevated calcium and PTH levels. Preoperative biopsy of patients with suspected parathyroid carcinoma is not recommended because of the risk of seeding the needle track with tumor. Because patients with parathyroid carcinoma often present with the same symptoms as patients with benign, sporadic primary hyperparathyroidism, the diagnosis is often assigned intraoperatively.10 Unlike a parathyroid adenoma, a parathyroid carcinoma appears as a firm, white-gray mass often adhering to surrounding tissues.

Consideration should be given to en bloc resection of the parathyroid with the ipsilateral thyroid lobe and/or locoregional lymph nodes if necessary for complete tumor resection.

Often, parathyroid carcinoma is not recognized at the first operation, and scar tissue at the second operation may increase the difficulty of recognizing parathyroid cancer. In these cases, persistent disease (defined as biochemical evidence of inappropriately elevated calcium 6 months after the first operation) and time to recurrence should be considered.

Microscopic and macroscopic classifications of the primary tumor have not been standardized. Whether size or extent of invasion affects overall survival remains controversial. Until more is known about prognostic features associated with the primary tumor in parathyroid carcinoma, the expert panel recommends classifying the primary tumor according to both size and extent of invasion.

The prognostic significance of regional lymph node involvement is unclear, and studies are conflicting.7,8,11-15 Until more is known about the prognostic significance of regional lymph node metastasis, the panel recommends collecting the type of lymph node dissection, the number of lymph nodes removed, and the number of lymph nodes with metastatic disease.

Parathyroid carcinoma is usually sporadic and may be associated with primary, secondary, or tertiary hyperparathyroidism. Patients with previous neck irradiation or certain hereditary syndromes may be at increased risk for developing parathyroid carcinoma. For instance, hyperparathyroidism-jaw tumor syndrome (HPT-JT) is a rare autosomal dominant disease caused by a mutation in the CDC73 (HRPT2) gene located on chromosome 1q25-32.16 Patients with this syndrome have ossifying fibromas of the jaw and various tumors/cysts of the kidneys, as well as Mullerian tract tumors in females. While 90% of patients develop primary hyperparathyroidism during their lifetime, as many as 15% develop parathyroid carcinoma.2

Familial isolated primary hyperparathyroidism is a rare autosomal dominant disease thought to be a variant of multiple endocrine neoplasia type I. This disease is also associated with an increased risk of developing parathyroid carcinoma.17

Imaging

Patients with parathyroid carcinoma often have imaging characteristics similar to those of patients with parathyroid adenomas. However, patients who are found to have a large mass, complex cystic lesions with internal septations, central necrosis, and/or compression of adjacent tissues should raise the preoperative suspicion of parathyroid carcinoma.10

Preoperative imaging studies may be performed in patients with a biochemical diagnosis of primary hyperparathyroidism to facilitate performance of a minimally invasive parathyroidectomy. This approach involves a focused resection of an abnormal parathyroid gland in conjunction with intraoperative PTH monitoring.18,19 If there is clinical suspicion for parathyroid carcinoma at operation, then en bloc resection of adjacent tissue (i.e. thyroid) and/or adjacent lymph nodes should be performed. Preoperative imaging is also essential in patients undergoing reoperative parathyroidectomy.20-24

The most commonly used imaging modalities include ultrasonography, which allows concurrent examination of the thyroid; technetium-99 sestamibi scanning (in conjunction with single-photon emission computed tomography [CT] and/or X-ray based CT); and four-dimensional CT, which uses thin-section dynamic scanning techniques with multiplanar reconstruction capabilities.25-29 In addition, fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography may be helpful for the detection of parathyroid carcinoma, particularly for recurrence of distant metastatic disease; however, current data on this imaging modality are limited. Several preoperative imaging algorithms have been proposed; the optimal algorithm is informed by institutional capabilities and knowledge of one's institutional resources, capabilities, reported sensitivities, and operative outcomes.30

The diagnosis of parathyroid carcinoma is based on a combination of clinical and histologic findings on the resected parathyroid gland. The most reliable criteria for the diagnosis of parathyroid carcinoma are the presence of vascular or perineural invasion, invasion into adjacent soft tissues, and/or regional and distant metastasis.1,2,31 Supportive findings include the presence of broad fibrous bands, necrosis, mitotic figures, and trabecular growth; although without the criteria noted earlier, these features are insufficient for a diagnosis of carcinoma. 1,2 Similarly, although the Ki-67 proliferation index (PI) is often elevated (>5%) in parathyroid carcinoma, this finding is not always conclusive because it may be elevated in benign disease.1

- Age at diagnosis

- Gender

- Race

- Size of primary tumor in millimeters

- Location of primary tumor: left or right and superior (upper) or inferior (lower)

- Invasion into surrounding tissue (present or absent)

- Distant metastasis

- Number of lymph nodes removed (by level)

- Number of lymph nodes positive (by level)

- Highest preoperative calcium (number in tenths in milligrams per deciliter [e.g., 11.5 mg/dL])

- Highest preoperative PTH (whole number in picograms per milliliter [e.g., 350 pg/mL])

- Lymphovascular invasion (present or absent)

- Grade (LG or HG)

- Weight of primary tumor (in milligrams)

- Mitotic rate

- Time to recurrence (months)