With the constant threat of accidental releases of hazardous materials and the potential criminal use of chemical weapons, local emergency response providers must be prepared to handle victims who may be contaminated with chemical substances. Many local jurisdictions have developed hazardous materials (HazMat) teams; these usually are composed of fire, environmental, and paramedical personnel trained to identify hazardous situations quickly and take the lead in organizing a response. Health care providers such as ambulance personnel, nurses, physicians, and local hospital officials should participate in emergency response planning and drills with their local HazMat team before a chemical disaster occurs.

- General considerations. The most important principles of successful medical management of a hazardous materials incident are the following:

- Use extreme caution when dealing with unknown or unstable conditions.

- Rapidly assess the potential hazard severity of the substances involved.

- Determine the potential for secondary contamination of nearby personnel and facilities.

- Perform any needed decontamination at the scene before victim transport, if possible.

- Organization. Chemical incidents are generally managed under an incident command system. The incident commander or scene manager is usually the senior representative of the agency that has primary traffic investigative authority, but this authority may be delegated to a senior fire or health official. The first priorities of the incident commander are to secure the area, establish a command post, create hazard zones, and provide for the decontamination and immediate prehospital care of any victims. However, hospitals must be prepared to manage victims who leave the scene before teams arrive and may arrive at the emergency department unannounced, possibly contaminated, and needing medical attention.

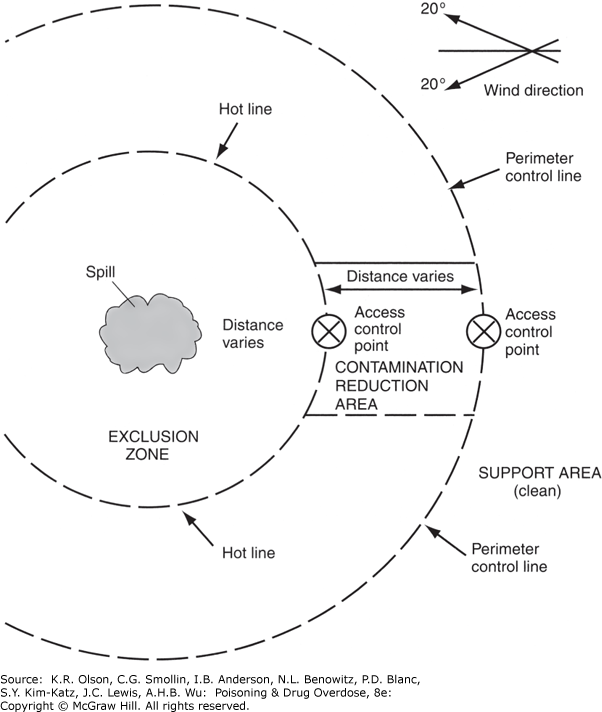

- Hazard zones (Figure IV-1) are determined by the nature of the spilled substance and the wind and geographic conditions. In general, the command post and support area are located upwind and uphill from the incident, with sufficient distance to allow rapid escape if conditions change.

- The exclusion zone (also known as the “hot” or “red” zone) is the area immediately adjacent to the chemical incident. This area may be extremely hazardous to persons without appropriate protective equipment. Only properly trained and equipped personnel should enter this zone, and they may require comprehensive decontamination when leaving the zone.

- The contamination reduction zone (also known as the “warm” or “yellow” zone) is where victims and rescuers are decontaminated before undergoing further medical assessment and prehospital care. Because of the limitations posed by protective equipment, patients in the exclusion zone and contamination reduction zone generally receive only rudimentary first aid and/or immediately life-saving interventions until they are decontaminated.

- The support zone (also known as the “cold” or “green” zone) is where the incident commander, support teams, media, medical treatment areas, and ambulances are situated. It is usually upwind, uphill, and a safe distance from the incident.

- Medical officer. A member of the HazMat team should already have been designated to be in charge of health and safety. This person is responsible, with help from the technical reference specialist, for determining the nature of the chemicals, the likely severity of their health effects, the need for specialized personal protective gear, the type and degree of decontamination required, and the supervision of triage and prehospital care. In addition, the medical officer, with the site safety officer, supervises the safety of response workers at the emergency site and monitors entry to and exit from the spill site. This person may also be in contact with receiving hospitals regarding the medical care and needs of the victims.

- Hazard zones (Figure IV-1) are determined by the nature of the spilled substance and the wind and geographic conditions. In general, the command post and support area are located upwind and uphill from the incident, with sufficient distance to allow rapid escape if conditions change.

- Assessment of hazard potential. Be prepared to recognize dangerous situations and respond appropriately. The potential for toxic or other types of injury depends on the chemicals involved, their toxicity, their chemical and physical properties, the conditions of exposure, and the circumstances surrounding their release. Be aware that the reactivity, flammability, explosiveness, or corrosiveness of a substance may be a source of greater hazard than its systemic toxicity. Do not depend on your senses for safety, even though sensory input (eg, smell) may give clues to the nature of the hazard.

- Identify the substances involved. Make inquiries and look for labels, warning placards, and shipping papers.

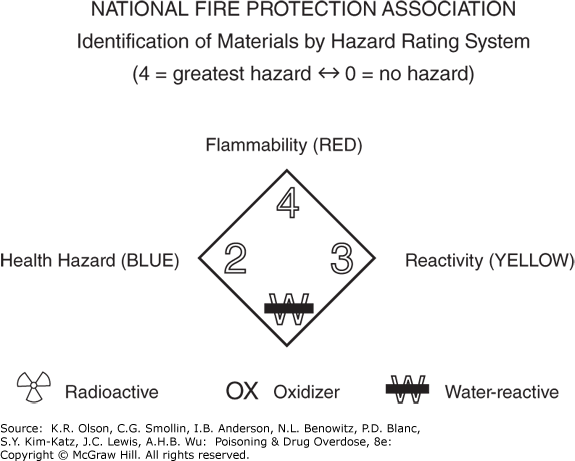

- The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) has developed a labeling system for describing chemical hazards that is widely used (Figure IV-2).

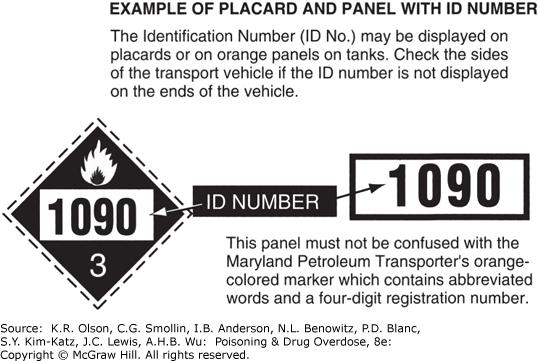

- The US Department of Transportation (DOT) has developed a system of warning placards for vehicles carrying hazardous materials. The DOT placards usually bear a four-digit substance identification code and a single-digit hazard classification code (Figure IV-3). Identification of the substance from the four-digit code can be provided by the regional poison control center, CHEMTREC, or the DOT manual (see Item B below).

- Shipping papers, which may include safety data sheets (SDSs), usually are carried by a driver or pilot or may be found in the truck cab or pilot's compartment.

- Obtain toxicity information. Determine the acute health effects and obtain advice on general hazards, decontamination procedures, and the medical management of victims. Resources include the following:

- Regional poison control centers (1-800-222-1222). The regional poison control center can provide information on immediate health effects, the need for decontamination or specialized protective gear, and specific treatment, including the use of antidotes. The regional center can also provide consultation with a medical toxicologist.

- The US Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) (1-770-488-7100) can provide emergency response teams comprised of toxicologists, physicians and other scientists to assist during a hazardous materials emergency.

- CHEMTREC. Operated by the American Chemistry Council, this 24-hour hotline can provide information on the identity and hazardous properties of chemicals and, when appropriate, can put the caller in touch with industry representatives and medical toxicologists. Note: users must be pre-registered to use the 24-hour emergency hotline service: call 1-800-262-8200 for information.

- See Table IV-3 and specific chemicals covered in Section II of this manual.

- A variety of texts, journals, and computerized information systems are available but are of uneven scope or depth. See the reference list at the end of this section.

- Recognize dangerous environments. In general, environments likely to expose rescuers to the same conditions that caused grave injury to the victim(s) are not safe for unprotected entry. These situations require trained and properly equipped rescue personnel. Examples include the following:

- Any indoor environment where the victim was rendered unconscious or otherwise disabled.

- Environments causing acute onset of symptoms in rescuers, such as chest tightness, shortness of breath, eye or throat irritation, coughing, dizziness, headache, nausea, and loss of coordination.

- Confined spaces such as large tanks or crawl spaces. (Their poor ventilation and small size can result in extremely high levels of airborne contaminants. In addition, such spaces permit only a slow or strenuous exit, which may become physically impossible for an intoxicated individual.)

- Spills involving substances with poor warning properties or high vapor pressures, especially when they occur in an indoor or enclosed environment. Substances with poor warning properties can cause serious injury without any warning signs of exposure, such as smell and eye irritation. High vapor pressures increase the likelihood that dangerous air concentrations may be present. Also note that gases or vapors with a density greater than that of air may become concentrated in low-lying areas.

- Determine the potential for secondary contamination. Although the threat of secondary contamination of emergency response personnel, equipment, and nearby facilities may be significant, it varies widely, depending on the chemical, its concentration, and whether basic decontamination has already been performed. Not all toxic substances carry a risk for secondary contamination, even though they may be extremely hazardous to rescuers in the hot zone. Exposures involving inhalation only and no external contamination generally do not pose a risk for secondary contamination.

- Examples of substances with no significant risk for secondary contamination of personnel outside the hot zone are gases, such as carbon monoxide, arsine, and chlorine, and vapors, such as those from xylene, toluene, and perchloroethylene.

- Examples of substances that have significant potential for secondary contamination and require aggressive decontamination and protection of nearby personnel include potent organophosphorus insecticides, oily nitrogen-containing compounds, and highly radioactive compounds such as cesium and plutonium.

- In many cases involving substances with a high potential for secondary contamination, this risk can be minimized by removing grossly contaminated clothing and thoroughly cleansing the body in the contamination reduction corridor, including washing with soap or shampoo. After these measures are followed, only rarely will the members of the medical team face significant, persistent personal threat to their health from an exposed victim.

- Identify the substances involved. Make inquiries and look for labels, warning placards, and shipping papers.

- Personal protective equipment. Personal protective equipment includes chemical-resistant clothing and gloves and protective respiratory gear. The use of such equipment should be supervised by experts in industrial hygiene or others with appropriate training and experience. Particular care should be given to donning and removing protective equipment. Equipment that is incorrectly selected, improperly fitted, poorly maintained, or inappropriately used may provide a false sense of security and may fail, resulting in secondary contamination or serious injury.

- Protective clothing may be as simple as a disposable apron or as sophisticated as a fully encapsulated chemical-resistant suit. However, no chemical-resistant clothing is completely impervious to all chemicals over the full range of exposure conditions. Each suit is rated for its resistance to specific chemicals, and many are also rated for chemical breakthrough time.

- Protective respiratory gear may be a simple paper mask, a cartridge filter respirator, or a positive-pressure air-supplied respirator. Respirators must be properly fitted for each user.

- A paper mask may provide partial protection against gross quantities of airborne dust particles but does not prevent exposure to gases, vapors, and fumes.

- Cartridge filter respirators filter certain chemical gases and vapors out of the ambient air. They are used only when the toxic substance is known to be adsorbed by the filter, the airborne concentration is low, and there is adequate oxygen in the ambient air.

- Air-supplied respirators provide an independent source of clean air. They may be fully self-contained units or masks supplied with air by a long hose. A self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) has a limited duration of air supply, from 5 to 30 minutes. Users must be fitted for their specific gear.

- Hazardous Waste Operations and Emergency Response (HAZWOPER) training and baseline medical examination for HazMat team members and hazardous materials specialists is required by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). These examinations should include evaluation for use of respiratory protection including SCBA.

- Victim management. Victim management includes rapid stabilization and removal from the exclusion zone, initial decontamination, delivery to emergency medical services personnel at the support zone perimeter, and medical assessment and treatment in the support area. Usually, only the HazMat team or other personnel with appropriate training and protective gear will be responsible for rescue from the hot zone, where skin and respiratory protection may be critical. Emergency medical personnel without specific training and appropriate equipment must not enter the hot zone unless it is determined to be safe by the incident commander and the medical officer.

- Stabilization in the exclusion zone. If there is suspicion of trauma, the patient should be placed on a backboard, with a cervical collar applied if appropriate. Position the patient so that the airway remains open. Gross contamination may be brushed off the patient. No further medical intervention can be expected from rescuers who are wearing bulky suits, masks, and heavy gloves. Therefore, every effort should be made to get a seriously ill patient out of this area as quickly as possible. Victims who are ambulatory should be directed to walk to the contamination reduction area.

- Initial decontamination. Gross decontamination may take place in the exclusion zone (eg, brushing off chemical powder and removing soaked clothing), but most decontamination occurs in the contamination reduction corridor before the victim is transferred to waiting emergency medical personnel in the support area. Do not delay critical treatment while decontaminating the victim unless the nature of the contaminant makes such treatment too dangerous. Consult a regional poison control center (1-800-222-1222) for specific advice on decontamination. See also Section I, Decontamination.

- Remove contaminated clothing and flush exposed skin, hair, or eyes with copious plain water from a high-volume, low-pressure hose. For oily substances, additional washing with soap or shampoo may be required. Ambulatory, cooperative victims may be able to perform their own decontamination.

- For eye exposures, remove contact lenses if present and irrigate eyes with plain water or, if available, normal saline dribbled from an intravenous bag. Continue irrigation until symptoms resolve or, if the contaminant is an acid or base, until the pH of the conjunctival sac is nearly normal (pH 6-8).

- Double-bag and save all removed clothing and jewelry.

- Collect runoff water if possible, but generally rapid flushing of exposed skin or eyes should not be delayed because of environmental concerns. Remember that protection of health takes precedence over environmental concerns in a hazardous materials incident.

- In the majority of incidents, basic victim decontamination as outlined earlier will substantially reduce or eliminate the potential for secondary contamination of nearby personnel or equipment. Procedures for cleaning equipment are contaminant-specific and depend on the risk for chemical persistence as well as toxicity.

- Treatment in the support area. Once the patient is decontaminated (if required) and released into the support area, triage, basic medical assessment, and treatment by emergency medical providers may begin. In the majority of incidents, once the victim has been removed from the hot zone and is stripped and flushed, there is little or no risk for secondary contamination of these providers, and sophisticated protective gear is not necessary. Simple surgical latex gloves, a plain apron, or disposable outer clothing is generally sufficient.

- Maintain a patent airway and assist breathing if necessary. Administer supplemental oxygen.

- Provide supportive care for shock, arrhythmias, coma, or seizures.

- Treat with specific antidotes if appropriate and available.

- Further skin, hair, or eye washing may be necessary.

- Take notes on the probable or suspected level of exposure for each victim, the initial symptoms and signs, and the treatment provided. For victims exposed to chemicals with delayed toxic effects, this can be lifesaving.

- Ambulance transport and hospital treatment. For skin or inhalation exposures, no special precautions should be required if adequate decontamination has been carried out in the field before transport.

- Patients who have ingested toxic substances may vomit en route; carry a large plastic bag-lined basin and extra towels to soak up and immediately isolate spillage. Vomitus may contain the original toxic material or even toxic gases created by the action of stomach acid on the substance (eg, hydrogen cyanide from ingested cyanide salts, phosphine gas from ingested aluminum phosphide). Ambulance ventilation should be set for a minimum of 24 air changes per hour for two people in 150 cubic feet of space (4.25 cubic meters). When performing gastric lavage in the emergency department, isolate gastric washings if possible (eg, with a closed-wall suction container system).

- For unpredictable situations in which a contaminated victim arrives at the hospital before decontamination, it is important to have a strategy ready that will minimize exposure of hospital personnel.

- Ask the local HazMat team to set up a contamination reduction area outside the hospital emergency department entrance. However, keep in mind that all teams may already be committed and not available to assist.

- Prepare in advance a hose with warm water at about 30°C (86°F), soap, and an old gurney for rapid decontamination outside the emergency department entrance. Have a child's inflatable pool or another container ready to collect water runoff, if possible. However, do not delay patient decontamination if water runoff cannot be contained easily.

- Do not bring patients soaked with liquids into the emergency department until they have been stripped and flushed outside, as the liquids may emit gas vapors and cause illness among hospital staff.

- For incidents involving radioactive materials or other highly contaminating substances that are not volatile, use the hospital's radiation accident protocol, which generally will include the following:

- Restricted access zones.

- Isolation of ventilation ducts leading out of the treatment room to prevent the spread of contamination throughout the hospital.

- Paper covering for floors and use of absorbent materials if liquids are involved.

- Protective clothing for hospital staff (gloves, paper masks, shoe covers, caps, and gowns).

- Double-bagging and saving all contaminated clothing and equipment.

- Monitoring to detect the extent and persistence of contamination (ie, using a radiation monitor for radiation incidents).

- Notifying appropriate local, state, and federal offices of the incident and obtaining advice on laboratory testing and decontamination of equipment.

- Summary. The emergency medical response to a hazardous materials incident requires prior training and planning to protect the health of response personnel and victims.

- Response plans and training should be flexible. The level of hazard and the required actions vary greatly with the circumstances at the scene and the chemicals involved.

- First responders should be able to do the following:

- Recognize potentially hazardous situations.

- Take steps to protect themselves from injury.

- Obtain accurate information about the identity and toxicity of each chemical substance involved.

- Use appropriate protective gear.

- Perform victim decontamination before transport to a hospital.

- Provide appropriate first aid and advanced supportive measures as needed.

- Coordinate their actions with those of other responding agencies, such as the HazMat team, police and fire departments, and regional poison control centers.

FIGURE IV-1. Control Zones at a Hazardous Materials Incident Site

Control zones at a hazardous materials incident site.

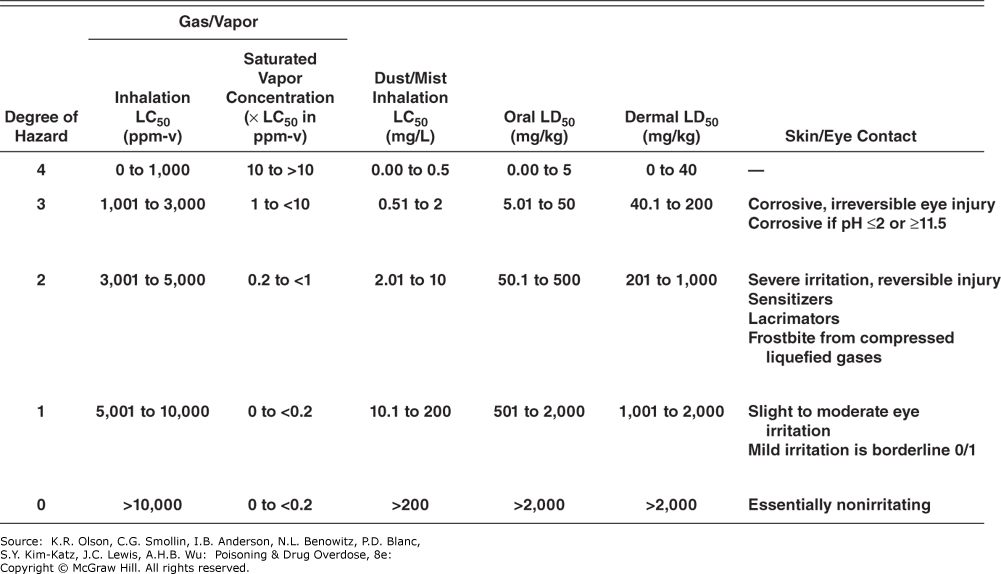

FIGURE IV-2. National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Identification of the Hazards of Materials (This Page) and Health Hazard Rating Chart (Next Page)

National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) identification of the hazards of materials (this page) and health hazard rating chart (next page). (Reproduced with permission of NFPA from NFPA 704, Standard System for the Identification of the Hazards of Materials for Emergency Response, 2017 edition. Copyright © 2016, National Fire Protection Association. For a full copy of NFPA 704, please go to www.nfpa.org.) National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) health hazard rating chart.

Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry (ATSDR): Managing Hazardous Materials Incidents (MHMIs). http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/MHMI/index.asp (An excellent resource for planning as well as emergency care, including prehospital and hospital management and guidelines for triage and decontamination.)

The ATSDR can also provide 24-hour expert assistance in emergencies involving hazardous substances in the environment: call 1-770-488-7100.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: NIOSH Pocket Guide to Occupational Hazards. http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npg (An excellent summary of workplace exposure limits and other useful information about the most common industrial chemicals.)

US Department of Transportation Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration: Emergency Response Guidebook (ERG2016). https://www.phmsa.dot.gov/sites/phmsa.dot.gov/files/docs/ERG2016.pdf

US National Library of Medicine: Wireless Information System for Emergency Responders (WISER). https://wiser.nlm.nih.gov (WISER is a system designed to assist first responders in hazardous material incidents. WISER provides a wide range of information on hazardous substances, including substance identification support, physical characteristics, human health information, and containment and suppression advice. It is freely available as a web-based tool, a downloadable freestanding version, or a mobile download for various mobile devices.)