- Emergency and supportive measures

- Spontaneous vomiting may delay the oral administration of antidote or charcoal (see below) and can be treated with metoclopramide or a serotonin (5-HT3) receptor antagonist such as ondansetron.

- Provide general supportive care for hepatic or renal failure if it occurs. Emergency liver transplant may be necessary for fulminant hepatic failure. Encephalopathy, metabolic acidosis, hypoglycemia, and a progressive rise in the prothrombin time are indications of severe liver injury.

- Specific drugs and antidotes

- Acute single ingestion or intravenous overdose

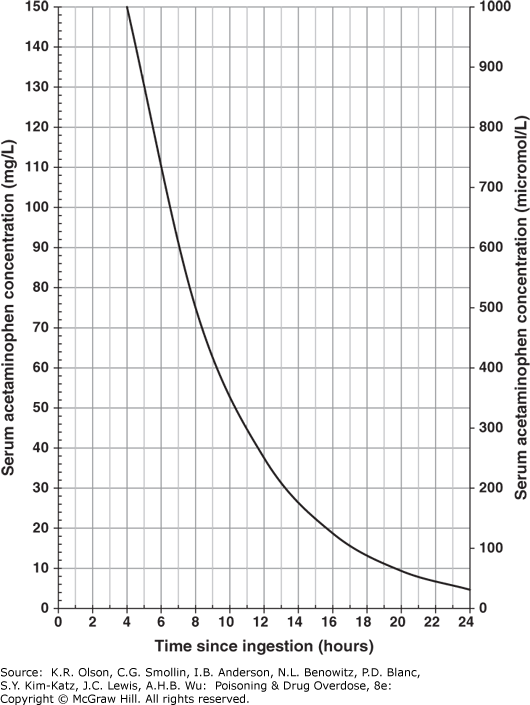

- If the serum level falls above the treatment line on the nomogram or if stat serum levels are not immediately available, initiate antidotal therapy with N-acetylcysteine (NAC). The effectiveness of NAC depends on early treatment, before the toxic metabolite accumulates; it is of maximal benefit if started within 8-10 hours and of diminishing value after 12-16 hours; however, treatment should not be withheld even if the delay is 24 hours or more. If vomiting interferes with or threatens to delay oral acetylcysteine administration, give the NAC IV.

- If the serum level falls below but near the nomogram line, consider giving NAC if the patient is at increased risk for toxicity—for example, if the patient is alcoholic, is taking a drug that induces CYP2E1 activity (eg, isoniazid [INH]), or has taken multiple or subacute overdoses—or if the time of ingestion is uncertain or unreliable.

- If the serum level falls well below the nomogram line, few clinicians would treat with NAC unless the time of ingestion is very uncertain or the patient is considered to be at particularly high risk.

- Note: After ingestion of extended-release tablets, which are designed for prolonged absorption, there may be a delay before the peak acetaminophen level is reached. This can also occur after co-ingestion of drugs that delay gastric emptying, such as opioids or anticholinergics. In such circumstances, repeat the serum acetaminophen level at 8 hours and possibly 12 hours. In such cases, it may be prudent to initiate NAC therapy before 8 hours while waiting for subsequent levels.

- Duration of NAC treatment. The conventional US protocol for the treatment of acetaminophen poisoning calls for 17 doses of oral NAC given over approximately 72 hours. However, for decades successful protocols in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Europe have used IV NAC for only 20 hours. In uncomplicated cases, give NAC (orally or IV) for 20 hours (or until acetaminophen levels are no longer detectable) and follow hepatic transaminase levels and the PT/INR; if evidence of liver injury develops, continue NAC until liver function tests are improving.

- Massive ingestion. Use a higher dose of NAC to treat very large overdoses (reported ingestions of >30 grams or if the measured serum acetaminophen level is greater than twice the nomogram line). See NAC, for detailed recommendations. Fomepizole (see), a potent inhibitor of cytochrome 2E1, may provide benefit as an adjunctive treatment by reducing the formation of NAPQI. Also consider early hemodialysis (see enhanced elimination below).

- Chronic or repeated acetaminophen ingestions: Patients may give a history of several doses taken over 24 hours or more, in which case the nomogram cannot accurately estimate the risk for hepatotoxicity. In such cases, we advise NAC treatment if the amount ingested was more than 200 mg/kg within a 24-hour period, 150 mg/kg/d for 2 days, or 100 mg/kg/d for 3 days or more and liver enzymes are elevated; or if there is detectable acetaminophen in the serum; or if the patient falls within a high-risk group (see above). Treatment may be stopped when acetaminophen is no longer detectable and the liver enzymes and PT/INR are normal or improving.

- Acute single ingestion or intravenous overdose

- Decontamination. Administer activated charcoal orally if conditions are appropriate (see Table I-37). Gastric lavage is not necessary after small-to-moderate ingestions if activated charcoal can be given promptly.

- Although activated charcoal adsorbs some of the orally administered antidote NAC, this effect is not considered clinically important.

- Do not administer charcoal if more than 1-2 hours has passed since ingestion unless delayed absorption is suspected (eg, as with extended release products or co-ingestants containing opioids or anticholinergic agents).

- Enhanced elimination. Hemodialysis effectively removes acetaminophen from the blood but is not generally indicated because antidotal therapy is so effective. Dialysis should be considered for massive ingestions with very high levels (eg, over 900-1,000 mg/L) complicated by severe acidosis, coma, and/or hypotension.

FIGURE II-1. Nomogram for Prediction of Acetaminophen Hepatotoxicity Following Acute Overdosage

Nomogram for prediction of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity following acute overdosage. Patients with serum levels above the line after acute overdose should receive antidotal treatment. (Reproduced with permission from Daly FF, Fountain JS, Murray L, Graudins A, Buckley NA; Panel of Australian and New Zealand clinical toxicologists. Guidelines for the management of paracetamol poisoning in Australia and New Zealand-explanation and elaboration. A consensus statement from clinical toxicologists consulting to the Australasian poisons information centres. Med J Aust. 2008;188(5):296-301. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01625.x)