In the UK 1 unit of alcohol is 10mL of ethanol or 1L of 1% alcohol. For example, 250mL of wine that is 10% alcohol contains 2.5 units. In the USA, one drink is defined as 14g (17.7mL) of ethanol (1.77 UK units). Other countries use somewhat different definitions based on volume or mass of alcohol.

The UK Department of Health has given the following advice and recommendations to minimise the health risks from alcohol consumption:1

- No more than 14 units should be consumed per week on a regular basis. This applies to both men and women.

- Harm is minimised when these units are spread across 3 or more days.

- Heavy, single-occasion drinking is associated with risk of harm, injury and accidents.

- The consumption of any volume of alcohol is still associated with a number of illnesses such as cancers of the throat, mouth and breast.

- There are no completely safe levels of drinking during pregnancy and precautionary avoidance of alcohol is recommended to reduce risk of harm to the baby.

The UK NICE guideline on the diagnosis, assessment and management of harmful drinking and alcohol dependence recommends that staff working in services that might encounter problem drinkers should be competent in identifying and assessing harmful drinking and alcohol dependence.2 The NICE public health guideline on reducing harmful drinking3 recommends a session of brief structured advice based on FRAMES principles (feedback, responsibility, advice, menu, empathy, self-efficacy) as a useful intervention for everyone at increased risk of alcohol-related problems.

Where consumption above recommended levels has been identified, a more detailed clinical assessment is required. Depending on the context, this could include the following:

- History of alcohol use, including daily consumption and recent patterns of drinking.

- History of previous episodes of alcohol withdrawal.

- Time of most recent drink.

- Collateral history from a family member or carer.

- Other drug (illicit and prescribed) use.

- Severity of dependence and of withdrawal symptoms.

- Coexisting medical and psychiatric problems.

- Physical examination including cognitive function.

- Breathalyser: absolute breath alcohol level and whether rising or falling (take at least 20 minutes after last drink to avoid falsely high readings from the mouth, and 1 hour later).

- Laboratory investigations: full blood count (FBC), urea and electrolytes (U&E), liver function tests (LFTs), international normalised ratio (INR), prothrombin time (PT) and urinary drug screen.

The following structured assessment tools are recommended:2

- The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) 4 questionnaire is a 10-item questionnaire which is useful as a screening tool in those identified as being at increasing risk. Questions 1-3 address the quantity of alcohol consumed, 4-6 the signs and symptoms of dependence and 7-10 the behaviours and symptoms associated with harmful alcohol use. Each question is scored 0-4, giving a maximum total score of 40. A score of 8 or more is suggestive of hazardous or harmful alcohol use. Hazardous drinking = consumption of alcohol likely to cause harm. Harmful drinking = consumption already causing mental or physical health problems.

- The Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire (SADQ) 5 is a more detailed 20-item questionnaire with the score on each item ranging from 0 to 3, giving a maximum total score of 60.

Severity of alcohol dependence | ||

| Mild | = | SADQ score of 15 or less |

| Moderate | = | SADQ score 15-30 |

| Severe | = | SADQ score >30 |

In alcohol-dependent drinkers, the central nervous system (CNS) has adjusted to the constant presence of alcohol in the body (neuroadaptation). When the blood alcohol concentration (BAC) is suddenly lowered, the brain remains in a hyper-excited state, resulting in the withdrawal syndrome (Tables 4.1 and 4.2). There is no evidence to support prophylactic use of additional anticonvulsant medication to prevent seizures in high-risk individuals.

Table 4.1 Mild Alcohol Withdrawal.

| Mild alcohol withdrawal manifestations | Usual timing of onset after last drink | Other information |

|---|---|---|

Agitation/anxiety/irritability Tremor of hands, tongue, eyelids Sweating Nausea/vomiting/diarrhoea Fever Tachycardia Systolic hypertension General malaise | Onset at 3-12 hours Peak at 24-48 hours Duration up to 14 days | Symptoms are non-specific Absence does not exclude withdrawal May commence before blood alcohol levels reach zero |

Management

| ||

Table 4.2 Severe Alcohol Withdrawal.

| Severe alcohol withdrawal complications | Usual timing of onset after last drink | Other information |

|---|---|---|

| Generalised seizures | 12-18 hours | May commence before blood alcohol levels reach zero |

Management

| ||

Delirium tremens Clouding of consciousness/confusion Vivid hallucinations, particularly in visual and tactile modalities Marked tremor Other clinical features also include: autonomic hyperactivity (tachycardia, hypertension, sweating and fever), paranoid delusions, agitation and insomnia Prodromal symptoms include: night-time insomnia, restlessness, fear and confusion Risk factors: severe alcohol dependence, self-detoxification without medical input, multiple previous admissions for alcohol withdrawal, concurrent medical illness, previous history of delirium tremens and alcohol withdrawal seizures, low potassium, low magnesium, thiamine deficiency, inadequately treated withdrawal Recognition is important because treatment is different from delirium arising from other causes; delirium tremens needs larger doses of benzodiazepines and more caution with antipsychotics | 3-4 days (72-96 hours) | Develops in 3-5% of those admitted to hospital for alcohol withdrawal A medical emergency Mortality 10-20% if untreated |

| Management Delirium tremens is a medical emergency and requires prompt transfer to a general hospital,9 preferably to a high-dependency setting.1011 | ||

Alcohol withdrawal is associated with significant morbidity and mortality when improperly managed.Pharmacologically assisted withdrawal is likely to be needed when:

- there has been regular consumption of >15 units/day

- AUDIT score >20

- there is a history of significant withdrawal symptoms.

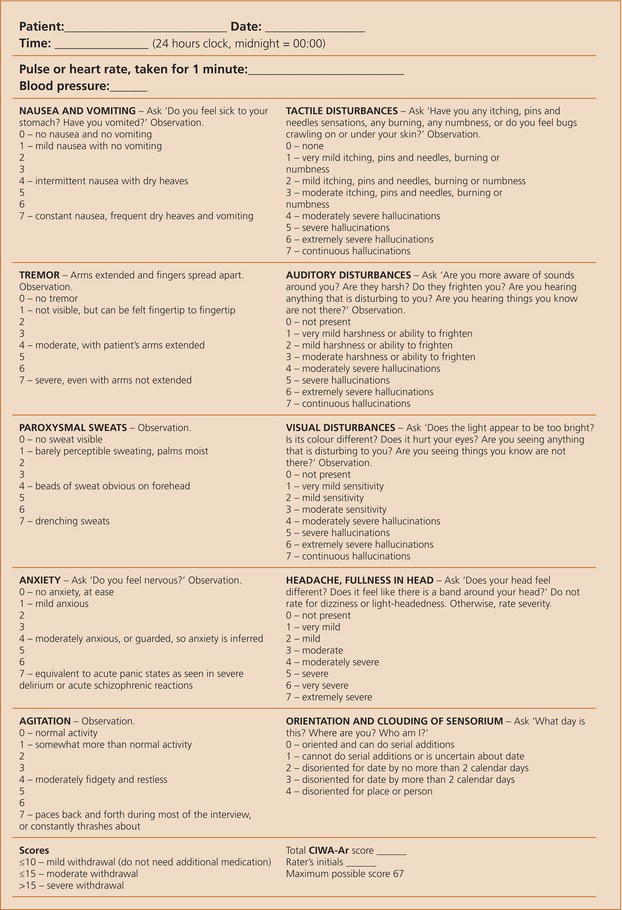

Symptom scales can be helpful in determining the amount of pharmacological support required to manage withdrawal symptoms. The Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale Revised (CIWA-Ar)12 (Figure ) and Short Alcohol Withdrawal Scale (SAWS)13 (Table 4.3) are both 10-item scales that can be completed in around 5 minutes. The CIWA-Ar is an objective scale and the SAWS is a self-complete tool. A CIWA-Ar score >10 or a SAWS score >12 should prompt assisted withdrawal.

Figure. 4.2.1 Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale, Revised (Ciwa-Ar). The Ciwa-Ar is Not Copyrighted and May Be Reproduced Freely.

Table 4.3 Short Alcohol Withdrawal Scale (SAWS).13

None (0) | Mild (1) | Moderate (2) | Severe (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxious | ||||

| Sleep disturbance | ||||

| Problems with memory | ||||

| Nausea | ||||

| Restless | ||||

| Tremor (shakes) | ||||

| Feeling confused | ||||

| Sweating | ||||

| Miserable | ||||

| Heart pounding |

Community detoxification is usually possible when:

- There is a supervising carer, ideally 24 hours a day throughout the duration of the detoxification process.

- The treatment plan has been agreed with the patient, their carer and their GP.

- A contingency plan has been agreed with the patient, their carer and their GP.

- The patient is able to pick up medication daily and be reviewed by professionals regularly throughout the process.

- Out-patient/community-based programmes including psychosocial support are available.

Community detoxification should be stopped if the patient resumes drinking or fails to engage with the agreed treatment plan.

In-patient detoxification is likely to be required if:

- Regular consumption is >30 units/day.

- SADQ >30 (severe dependence).

- There is a history of seizures or delirium tremens.

- The patient is a minor or an older adult.

- There is current benzodiazepine use in combination with alcohol.

- Substances other than alcohol are also being misused.

- There is comorbid mental or physical illness, learning disability or cognitive impairment.

- The patient is pregnant.

- The patient is homeless or has no social support.

- There is a history of failed community detoxification.

In certain situations, there may be a clinical justification for undertaking a community detoxification in these patients, however the reasons must be clear and the decision made by an experienced clinician.

Table 4.4 summarises common interventions used in alcohol withdrawal.

Table 4.4 Alcohol Withdrawal Treatment Interventions - a Summary.

| Severity | Supportive/medical care | Pharmacotherapy for neuroadaptation reversal | Thiamine supplementation | Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Mild CIWA-Ar ≤10 | Moderate- to high-level supportive care, little if any medical care required | Little to none required Simple remedies only (see below) | Oral likely to be sufficient if patient is well nourished | Home |

Moderate CIWA-Ar ≤15 | Moderate- to high-level supportive care, little medical care required | Little to none required Symptomatic treatment only | Intramuscular thiamine should be offered if the patient is malnourished followed by oral supplementation | Home or community team |

Severe CIWA-Ar >15 | High-level supportive care plus medical monitoring | Symptomatic and substitution treatment (chlordiazepoxide) probably required | Intramuscular thiamine should be offered followed by oral supplementation | Community team or hospital |

CIWA-Ar >10 + comorbid alcohol-related medical problems | High-level supportive care plus specialist medical care | Symptomatic and substitution treatments usually required | Intramuscular thiamine followed by oral supplementation | Hospital |

Benzodiazepines are the treatment of choice for alcohol withdrawal. They exhibit cross-tolerance with alcohol and have anticonvulsant properties. Their use is supported by NICE guidelines,2, 14 a Cochrane systematic review7 and British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines.9 Parenteral thiamine (vitamin B1) and other vitamin replacement is an important adjunctive treatment for the prophylaxis and/or treatment of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome and other vitamin-related neuropsychiatric conditions.

In the UK, chlordiazepoxide is the benzodiazepine used for most patients in most centres as it is considered to have a relatively low dependence-forming potential. Some centres use diazepam. A short-acting benzodiazepine such as oxazepam or lorazepam may be used in individuals with impaired liver function or those who potentially may metabolise medication more slowly, such as older people.

There are three types of assisted withdrawal regimens: fixed-dose reduction (the most common in non-specialist settings), variable-dose reduction (usually results in less benzodiazepine being administered but best reserved for settings where staff have specialist skills in managing alcohol withdrawal) and finally front-loading (infrequently used, and reserved for severe alcohol withdrawal).2, 9 Assisted withdrawal regimens should never be started if the blood alcohol concentration is very high or is still rising. Monitor patients for oversedation/respiratory depression.

Fixed-dose regimens can be used in community or non-specialist in-patient/residential settings for uncomplicated patients. Patients should be started on a dose of benzodiazepine selected after an assessment of the severity of alcohol dependence (clinical history, number of units per drinking day and score on the SADQ). With respect to chlordiazepoxide, a general rule of thumb is that the starting dose can be estimated from current alcohol consumption. For example, if 20 units/day are being consumed, the starting dose should be 20mg four times a day. The dose is then tapered to zero over 5-10 days. Alcohol withdrawal symptoms should be monitored using a validated instrument such as the CIWA-Ar12 or SAWS.13

Mild alcohol dependence usually requires very small doses of chlordiazepoxide or else may be managed without medication.

For moderate alcohol dependence, a typical regimen might be 10-20mg chlordiazepoxide four times a day, reducing gradually over 5-7 days (Table 4.5). This duration of treatment is usually adequate and longer treatment is rarely helpful or necessary. It is advisable to monitor withdrawal and BAC daily before providing the day's medication. This may mean that community pharmacologically assisted alcohol withdrawals should start on a Monday and last for 5 days.

Table 4.5 Moderate Alcohol Dependence: Example of a Fixed-Dose Chlordiazepoxide Treatment Regimen.

| Day | Dose | Total daily dose (mg) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20mg four times a day | 80 |

| 2 | 15mg four times a day | 60 |

| 3 | 10mg four times a day | 40 |

| 4 | 5mg four times a day | 20 |

| 5 | 5mg twice a day | 10 |

Severe alcohol dependence usually requires in-patient treatment for assisted withdrawal because of the significant risk of life-threatening complications. However, there are rare occasions where a pragmatic community approach is required. In such situations, the decision to undertake a community-assisted withdrawal must be made by an experienced clinician. Intensive daily monitoring is advised for the first 2-3 days. This may require special arrangements over a weekend.

Prescribing should not start if the patient is intoxicated. In such circumstances, they should be reviewed at the earliest opportunity when not intoxicated. The dose of benzodiazepine may need to be reduced over a 7-10-day period in this group (occasionally longer if dependence is very severe or there is a history of complications during previous detoxifications) (Table 4.6).

Table 4.6 Severe Alcohol Dependence: Example of a Fixed-Dose Chlordiazepoxide Regimen.

| Day | Dose | Total daily dose (mg) |

|---|---|---|

| &numsp1 (first 24 hours) | 40mg four times a day + 40mg when necessary | 200 |

| 2 | 40mg four times a day | 160 |

| 3 | 30mg four times a day | 120 |

| 4 | 25mg four times a day | 100 |

| 5 | 20mg four times a day | 80 |

| 6 | 15mg four times a day | 60 |

| 7 | 10mg four times a day | 40 |

| 8 | 10mg four times a day | 30 |

| 9 | 5mg four times a day | 20 |

| 10 | 10mg at night | 10 |

This should be reserved for managing assisted withdrawal in specialist alcohol in-patient or residential settings. Regular monitoring is required (e.g. pulse, blood pressure, temperature and level of consciousness). Medication is only given when withdrawal symptoms are observed as determined using CIWA-Ar, SAWS or an alternative validated measure. Symptom-triggered therapy is generally used in patients without a history of complications. A typical symptom-triggered regimen would be chlordiazepoxide 20-30mg hourly as needed. The total dose given each day would be expected to decrease from day 2 onwards. It is common for symptom-triggered treatment to last only 24-48 hours before switching to an individualised fixed-dose reducing schedule. Occasionally (e.g. in delirium tremens) the flexible regimen may need to be prolonged beyond the first 24 hours.

|

Carbamazepine is an alternative to a benzodiazepine for managing withdrawal in situations where benzodiazepines are not a safe first-line option.15, 16 Examples include:

- A history of adverse reaction or allergy to benzodiazepine drugs.

- A preference for carbamazepine because of a history of harmful or dependent use of benzodiazepines.

Wernicke's encephalopathy is an acute neuropsychiatric condition caused by thiamine deficiency. In alcohol dependence, thiamine deficiency is secondary to both reduced dietary intake and reduced absorption.

Risk factors for Wernicke's encephalopathy in alcohol dependence are:16

- acute withdrawal

- malnourishment

- decompensated liver disease

- emergency department attendance

- hospitalisation for comorbidity

- homelessness

- memory disturbance

- peripheral neuropathy

- previous history of Wernicke's encephalopathy.

The ‘classic' triad of ophthalmoplegia, ataxia and confusion is rarely present in Wernicke's encephalopathy, and the syndrome is much more common than is recognised. A presumptive diagnosis of Wernicke's encephalopathy should therefore be made in any patient undergoing detoxification who experiences any of the following signs:

- ataxia

- hypothermia

- hypotension

- confusion

- ophthalmoplegia/nystagmus

- memory disturbance

- unconsciousness/coma.

Any history of malnutrition, recent weight loss, vomiting or diarrhoea or peripheral neuropathy should also be taken into consideration.17

Low-risk drinkers without neuropsychiatric complications and with an adequate diet should be offered oral thiamine. The dose should be 300mg daily during assisted alcohol withdrawal and periods of continued alcohol intake.9 As thiamine is required to utilise glucose, a glucose load in a thiamine-deficient patient can precipitate Wernicke's encephalopathy.

Historically it has been advised that patients undergoing in-patient detoxification should be given parenteral thiamine as prophylaxis against Wernike's encephalopathy.2, 9, 18, 19 In many countries, there are no licensed forms of parenteral thiamine available.

In the UK, NICE20 recommends offering prophylactic parenteral thiamine followed by oral thiamine to those defined as ‘harmful or dependent drinkers' if they are also known to:

- be malnourished or at risk of malnourishment or

- have decompensated liver disease

- they attend an emergency department or

- are admitted to hospital with an acute injury or illness.

People at high risk of Wernicke's encephalopathy can have a range of conditions, including:

- significant weight loss

- poor diet

- low body mass index (BMI) (<18)

- other signs of malnutrition.

Consider offering prophylactic parenteral thiamine to people at high risk following the dosing below.

|

Hospital Setting Doses

|

If Wernicke's encephalopathy is suspected the patient should be transferred to a medical unit where intravenous thiamine can be administered. If untreated, Wernicke's encephalopathy progresses to Korsakoff's syndrome (permanent memory impairment, confabulation, confusion and personality changes).

Somatic complaints are common during assisted withdrawal. Table 4.7 lists some remedies.

Table 4.7 Treatment of Somatic Symptoms.

Symptom | Recommended treatment |

|---|---|

| Dehydration | Ensure adequate fluid intake in order to maintain hydration and electrolyte balance; dehydration can precipitate life-threatening cardiac arrhythmia |

| Pain | Paracetamol (acetaminophen) |

| Nausea and vomiting | Metoclopramide 10mg or prochlorperazine 5mg 4-6 hourly |

Diarrhoea | Diphenoxylate and atropine (Lomotil) or loperamide |

Skin itching | Occurs commonly and not only in individuals with alcoholic liver disease: use oral antihistamines |

There is no place for the continued use of benzodiazepines beyond treatment of the acute alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Acamprosate and supervised disulfiram are licensed in some countries for the treatment of alcohol dependence and may be offered in combination with psychosocial treatment.2 Treatment should be initiated by a specialist service. After 12 weeks, transfer of the prescribing to primary care may be appropriate, although specialist care may continue. Naltrexone is also recommended as an adjunct in the treatment of moderate and severe alcohol dependence.2 As it does not have marketing authorisation for the treatment of alcohol dependence in some countries, informed consent should be sought and documented prior to commencing treatment. A large number of new and repurposed agents are undergoing evaluation for the treatment of alcohol use disorder (AUD).23, 24

Acamprosate is a synthetic taurine analogue that acts as a functional glutamatergic N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist and also increases gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) function. The number needed to treat (NNT) for the maintenance of abstinence has been calculated as 9-11.9 Acamprosate should be initiated as soon as possible after abstinence has been achieved although the British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus guidelines11 recommend that acamprosate should be started during detoxification because of its potential neuroprotective effect. In the UK, NICE2 recommends that acamprosate should be continued for up to 6 months, with regular (monthly) supervision (Box 4.1). The summary of product characteristics (SPC) recommends that it is given for 1 year.

Acamprosate is relatively well tolerated. Adverse effects include diarrhoea, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and pruritis.2 It is contraindicated in severe renal or hepatic impairment, thus baseline liver and kidney function tests should be performed before commencing treatment. Acamprosate should be avoided in individuals who are pregnant or breastfeeding.

Acamprosate should be offered for relapse prevention in moderately to severely dependent drinkers, in combination with psychosocial treatment. It should be prescribed for up to 6 months, or longer for those who perceive benefit and wish to continue taking it. The dose is 1998mg daily (666mg three times per day) for individuals over 60kg. For those under 60kg, the dose is 1332mg daily. Treatment should be stopped in those who continue to drink for 4-6 weeks after starting the drug. |

Opioid blockade prevents increased dopaminergic activity after the consumption of alcohol, thus reducing its rewarding effects. Naltrexone, a non-selective opioid receptor antagonist, significantly reduces relapse to heavy drinking.2, 24 Although early trials used a dose of 50mg/day, later US studies have used 100mg/day. In the UK the usual dose is 50mg/day with a trial dose of 25mg for 2 days to evaluate for adverse effects (Box 4.2).

Naltrexone is well tolerated but adverse effects include nausea (especially in the early stages of treatment), headache, abdominal pain, reduced appetite and tiredness. A comprehensive medical assessment should be carried out prior to commencing naltrexone, together with baseline renal and liver function tests. Naltrexone can be started when patients are still drinking or during medically assisted withdrawal. There is no clear evidence as to the optimal duration of treatment but 6 months appears to be an appropriate period with follow-up, including monitoring liver function.9

Patients on naltrexone should not be given opioid agonist drugs for analgesia, non-opioid analgesics should be used instead. In the event that opioid analgesia is necessary, it can be instituted 48-72 hours after cessation of naltrexone. Hepatotoxicity has been described with high doses of naltrexone, so use should probably be avoided in acute liver failure.25

Long-acting injectable naltrexone has been developed to improve compliance.26 Adverse effects are similar to those seen with the oral preparation.27 In the UK, NICE concluded that the initial evidence was encouraging but not enough to support routine use.

Naltrexone (50mg/day) should be offered for relapse prevention in moderately to severely dependent drinkers in combination with psychosocial treatment. It should be prescribed for up to 6 months, or longer for those who perceive benefit and wish to continue taking it. Treatment should be stopped in those who continue to drink for 4-6 weeks after starting the drug or in those who feel unwell while taking it. |

Nalmefene is also an opioid antagonist, recommended by NICE as an option for reducing alcohol consumption in people with alcohol dependence.2, 24 It has been shown in one meta-analysis to be superior to naltrexone in reducing heavy drinking.28 However, use of nalmefene remains controversial, with another meta-analysis suggesting that nalmefene had only limited efficacy in reducing alcohol consumption and that its value in treating alcohol addiction and relapse prevention is not fully established.29 Nalmefene's efficacy is better than placebo30 but its place in therapy has yet to be established.

Disulfiram is a second-line treatment for those with moderate or severe alcohol dependence who have successfully completed withdrawal and want to maintain abstinence.31 It acts by inhibiting the enzyme aldehyde dehydrogenase, thus preventing complete metabolism of alcohol in the liver. This results in an accumulation of the toxic intermediate product, acetaldehyde, which causes the alcohol-disulfiram reaction, acting as a deterrent for further alcohol use (Table 4.8). Supervised medication optimises compliance and contributes to effectiveness.

Table 4.8 The Alcohol-Disulfiram Reaction.

| Mild alcohol-disulfiram reaction | Severe alcohol-disulfiram reaction | Contraindications |

|---|---|---|

Facial flushing Sweating Nausea Hyperventilation Dyspnea Tachycardia Hypotenision | Acute heart failure Myocardial infarction Arrhythmias Bradycardia Respiratory depression Severe hypotension | Ingestion of alcohol within the previous 24 hours Cardiac failure Coronary artery disease Hypertension Cerebrovascular disease Pregnancy Breastfeeding Liver disease Peripheral neuropathy Severe mental illness |

The intensity of the intolerance reaction is dose-dependent, with regard to both the amount of alcohol consumed and the dose of disulfiram. However, it is thought that much of the therapeutic effect is mediated by the mental anticipation of the aversive reaction, rather than the pharmacological action itself. Sudden death can occur but is more prevalent at disulfiram doses above 1000mg.31 With this in mind, the value of prescribing higher doses of disulfiram must be carefully considered.

The first dose is usually 800mg, reducing to 100-200mg daily for maintenance. In comorbid alcohol and cocaine dependence doses of 500mg daily have been given. Halitosis is a common adverse effect. If there is a sudden onset of jaundice (signalling the rare complication of hepatotoxicity), the patient should stop the drug and seek urgent medical attention.

The evidence for disulfiram is weaker than for acamprosate and naltrexone2 although its effect size may be greater.32 In the UK, NICE recommends its use ‘as a second-line option for moderate to severe alcohol dependence for patients who are not suitable for acamprosate or naltrexone or have a specified preference for disulfiram and who aim to stay abstinent from alcohol' (Box 4.3).2

Disulfiram should be considered in combination with a psychological intervention for patients who wish to achieve abstinence, but for whom acamprosate or naltrexone are not suitable. Treatment should be started at least 24 hours after the last drink and should be overseen by a family member or carer. Monitoring is recommended every 2 weeks for the first 2 months, then monthly for the following 4 months. Medical monitoring should be continued at 6-monthly intervals after the first 6 months. Patients must not consume any alcohol while taking disulfiram. |

Baclofen is a GABA-B agonist that does not have a licence for use in alcohol dependence but is nevertheless used by some clinicians as second-line treatment for those who have not responded to either naltrexone or acamprosate, or where there are contraindications for first-line treatment. A 2023 Cochrane review suggested that baclofen may help people with AUD in maintaining abstinence, particularly in people who are already detoxified.33 A 2022 meta-analysis32 also suggested baclofen is effective but is associated with higher rates of adverse effects including depression, vertigo, somnolence, numbness and muscle rigidity.

There is currently insufficient evidence to support the use of antiseizure medications in the treatment of alcohol dependence, although they may reduce the number of drinks per drinking day compared with placebo.34 The majority of the research has been carried out on topiramate. Topiramate acts as a GABA/glutamate modulator that has demonstrated safety and efficacy in reducing heavy drinking in patients without AUD.35 It may as effective as naltrexone in AUD.36

There have been fewer studies on gabapentin,37 valproate and levetiracetam.30 Although these drugs have been used elsewhere in the world, they are not routinely used in the UK owing to lack of evidence and concerns regarding safety profiles for both gabapentin and valproate.

Evidence indicates that alcohol consumption during pregnancy may cause harm to the fetus. The Department of Health advises that women should not drink any alcohol at all during pregnancy.1 Drinking even 1-2 units/day during pregnancy can increase the risk of having a preterm, low birthweight or small for gestational age baby.

For alcohol-dependent pregnant women who have withdrawal symptoms, pharmacological cover for detoxification should be offered, ideally in an in-patient setting in collaboration with an antenatal team. The timing of detoxification in relation to the trimester of pregnancy should be risk-assessed against continued alcohol consumption and risks to the fetus.9 Chlordiazepoxide has been suggested as being unlikely to pose a substantial risk, however dose-dependent malformations have been observed.11 The UK Teratology Information Service (UKTIS)38 provides national advice for healthcare professionals and likes to follow up on pregnancies that require alcohol detoxification. Specialist advice should always be sought. (See also Chapter 7.) No relapse prevention medication has been evaluated in pregnancy.9

The number of young people who are dependent and needing pharmacotherapy is small, but for those who are dependent there should be a lower threshold for admission to hospital. Doses of chlordiazepoxide for medically assisted withdrawal may need to be adjusted, but the general principles of withdrawal management are the same as for adults. All young people should have a full health screen carried out routinely to allow identification of physical and mental health problems. Relapse prevention medications are not licensed in the under 18 population due to lack of evidence. The evidence base for acamprosate, naltrexone and disulfiram in 16-19-year-olds is evolving,9 but naltrexone is best supported in this age group.39, 40, 41

For older adults, there should be a lower threshold for hospital admission for medically assisted alcohol withdrawal.2 Benzodiazepines remain the treatment of choice but they may need to be prescribed in lower doses and in some situations shorter acting drugs may be preferred.9 All older adults with AUD should have full routine health screens to identify physical and mental health problems. The evidence base for pharmacotherapy of AUD in older people is limited.42

Where alcohol and drug use disorders are comorbid, treat both conditions actively.2

This is best managed with one benzodiazepine, either chlordiazepoxide or diazepam. The starting dose should take into account the requirements for medically assisted alcohol withdrawal and the typical daily equivalent dose of the relevant benzodiazepine(s).2, 43 In-patient treatment should be carried out over a 2-3-week period, possibly longer.2

In comorbid cocaine/alcohol dependence, naltrexone 150mg/day resulted in reduced cocaine and alcohol use in men but not in women.44 Topiramate seems ineffective.45

Both conditions should be treated and attention paid to the increased mortality of individuals withdrawing from both drugs.

Encourage individuals to stop smoking. Refer for smoking cessation in primary care and other settings. In in-patient settings offer nicotine patches/inhalator during assisted alcohol withdrawal. Always promote vaping as a safer alternative to tobacco smoking.

People with AUD often present with other mental health disorders, particularly anxiety and depression. Public Health England has described it as ‘the norm rather than the exception' and encourages a collaborative, effective and flexible approach between front-line services, stating that it is ‘everyone's job' and that there is ‘no wrong door'.46

Substance use disorders, including AUD, should never be a reason to exclude a patient from crisis or specialist psychiatric services after completion of detoxification.

Depressive and anxiety symptoms occur commonly during alcohol withdrawal, but usually diminish by the 3rd or 4th week of abstinence. Meta-analyses suggest that antidepressants with mixed pharmacology (the tricyclics imipramine or trimipramine) perform better than selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs; fluoxetine or sertraline) in reducing depressive symptoms in individuals with AUD, but the antidepressant effect is modest.2, 9, 47, 48 Trazodone may also be effective.49 A greater antidepressant effect was seen if the diagnosis of depression was made after at least 1 week of abstinence, thus excluding those with affective symptoms caused by alcohol withdrawal. There is stronger evidence for depression categorised as independent rather than substance-induced.36 As treatment effects are masked by comparatively large placebo effects, which conceal improvements that would otherwise be attributed to medication, there is a need for larger randomised, placebo-controlled trials. Despite the evidence for tricyclics, they are rarely used in clinical practice because of their potential for cardiotoxicity and toxicity in overdose.50 SSRIs may not be effective in depression in AUD and may worsen drinking behaviour.51

Relapse prevention medication should be considered in combination with antidepressants. Pettinati et al.52 showed that the combination of sertraline (200mg/day) with naltrexone (100mg/day) had superior outcomes - improved drinking outcomes and better mood - compared with placebo and compared with each drug alone. In contrast, citalopram showed no benefit when added to naltrexone.53

Secondary analyses of acamprosate and naltrexone trials suggest that:

- Acamprosate has an indirect modest beneficial effect on depression via increasing abstinence.

- In depressed alcohol-dependent patients, the combination of naltrexone and an antidepressant may be better than either drug alone,9 but findings are not consistent.53

Ketamine is an emerging treatment for AUD54 and may be helpful in comorbid depression.

Bipolar patients tend to use alcohol to reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression, and comorbid AUD is common. Where there is comorbidity, it is important to treat the different phases of bipolar disorder as recommended elsewhere. It may be worth adding sodium valproate to lithium as the combination is associated with better drinking outcomes than lithium alone. However, the combination did not confer any extra benefit than lithium alone in improving mood (see British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus 2012).9 In those who continue to drink, electrolyte imbalance may precipitate lithium toxicity. Lithium is probably best avoided completely in binge drinkers. Adding quetiapine to lithium or valproate has no effect.55

Naltrexone should be offered early to help bipolar patients reduce their alcohol consumption.9 If naltrexone is not effective, then acamprosate should be offered. In the event that both naltrexone and acamprosate fail to promote abstinence, then disulfiram should be considered, and the risks made known to the patient.

Anxiety is commonly observed in alcohol-dependent individuals during intoxication, withdrawal and in the early days of abstinence. Alcohol is typically used to self-medicate anxiety disorders, particularly social anxiety. In alcohol-dependent individuals who experience anxiety it is often difficult to determine the extent to which the anxiety is a symptom of the AUD or whether it is an independent disorder. Medically assisted withdrawal and supported abstinence for up to 8 weeks are required before a full assessment can be made. If a medically assisted withdrawal is not possible then treatment of the anxiety disorder should still be attempted, following guidelines for the particular anxiety disorder.

The use of benzodiazepines is controversial11 because of the increased risk of benzodiazepine misuse and dependence. Benzodiazepines should only be considered following assessment in a specialist addiction service. Long-term use is generally not recommended.51

One meta-analysis suggested that buspirone is effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety but not alcohol consumption.9, 56 Studies have also shown that paroxetine (up to 60mg/day) was superior to placebo in reducing social anxiety in AUD patients although alcohol consumption was not affected.9, 56

Either naltrexone or disulfiram, alone or combined, improves drinking outcomes compared with placebo in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and alcohol dependence.57, 58 Both acamprosate and baclofen have shown benefit in reducing anxiety in post hoc analyses of alcohol-dependence trials. It is therefore important to ensure that these patients are enabled to become abstinent and are prescribed relapse prevention medication. Anxiety should then be treated according to the appropriate NICE guidelines.

Patients with schizophrenia who also have AUD should be assessed and alcohol-specific relapse prevention treatment considered, usually either naltrexone or acamprosate. Disulfiram is contraindicated in psychosis.59 Antipsychotic medication should be optimised11 and clozapine may be considered. However, there is insufficient evidence to recommend the use of any one antipsychotic medication over another in AUD. Antipsychotics do not improve AUD itself.51