This section deals with covert medication administration within UK law only. Other countries may have different laws pertaining to this area, or indeed no laws or official guidance.1

In mental health settings it is common for patients to refuse medication. People with psychiatric disorders may lack capacity to make an informed choice about whether medication will be beneficial to them or not. In these cases, the clinical team may consider whether it would be in the patient's best interests to administer medication covertly. This practice is known as covert administration of medicines. Guidance from the Royal Pharmaceutical Society and Royal College of Nursing2 and the Royal College of Psychiatrists3 has been published in order to protect patients from the unlawful and inappropriate administration of medication in this way. In the UK, the legal framework for such interventions is either the Mental Capacity Act (MCA)4 or, more rarely, the Mental Health Act (MHA).5

The assessment of capacity regarding medication is primarily a matter for the prescriber, usually a doctor treating the patient,4, 6 or less commonly a pharmacist or nurse. Nurses and allied health professionals who are not prescribers will also have to be mindful of their own codes of professional practice and should be satisfied that the doctor's assessment is reasonable. The assessment must be made in relation to the particular treatment proposed as part of a covert medication care plan. Capacity can vary over time and the assessment should be made at the time of the proposed treatment. The assessment should be documented in the patient's notes and recorded in the care plan. Assessment of capacity should be conducted in line with the MCA code of practice.

If a patient has the capacity to give a valid refusal to medication and is not detainable under the MHA, their refusal should be respected.

If a patient has the capacity to give a valid refusal and is either being treated under the MHA or is legally detainable under the Act, the provisions of the MHA with regard to treatment will apply (which are outside the scope of this chapter).

The administration of medicines to patients who lack the capacity to consent and who are unable to appreciate that they are taking medication (e.g. unconscious patients) should not need to be carried out covertly. However, some patients who lack the capacity to consent would be aware of receiving medication if they were not deceived into thinking otherwise,7 for example a patient with moderate dementia who has no insight and does not believe they need to take medication but will take liquid medication if this is mixed with their tea without being aware of this. It is this group to whom this guidance applies.

Treatment may be given to people who lack capacity if the treatment is in the patient's best interests (Section 5, MCA4) and is proportionate to the harm to be avoided (Chapter 6.41, MCA Code of Practice7). So, there should be a clear expectation that the patient will benefit from covert administration, and that this will avoid significant harm (either mental or physical) to the patient or others. The treatment must be necessary to save the patient's life, to prevent deterioration in health or to ensure an improvement in physical or mental health.4, 7

Covert administration must be the least restrictive option after trying all other options. An assessment should be carried out to understand why the person is refusing to take their medicines. Alternative methods of administration (e.g. liquid formulation) and trial of different approaches in nursing care (e.g. explaining to the patient about the medicines at the time they are administered or changing the time of administration to a time of day when the patient is more alert or less distressed) should be considered.8

The decision to administer medication covertly should not be made by a single individual but through discussion with the multidisciplinary team caring for the patient and the patient's relatives or informal carers. A Best Interests meeting should be held, except in urgent situations if the decision cannot wait, in which case a less formal decision can take place with a view to arranging a Best Interests meeting as soon as practicably possible. If it were determined at this meeting that the provision of covert medication would amount to a deprivation of liberty (where previously there was none), then an application for Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) authorisation should be made. Decisions regarding covert administration of medication should be carefully documented in the patient's medical records with a clear management plan, including details of how the covert medication plan will be reviewed. This documentation must be easily accessible on viewing the person's records and the decision should be subject to regular review.

It is not necessary to have a new Best Interests meeting each time there is a change in medication. However, when covert medication is first considered, healthcare professionals should consider what types of changes in medication may be anticipated in future and should agree on the thresholds of what changes may require a new Best Interests meeting. This management plan should be recorded in the patient's notes. If significant changes that could cause adverse effects are envisaged, then a new meeting should be held before changes are made.

In deciding how often capacity assessments should be repeated, clinicians should follow the guidance within the practical guide to the MCA.6 If there is any evidence that the patient has regained capacity with regard to administration of their medication, an immediate capacity assessment must be done. Decisions in the patient's best interest can no longer be made if they are under a DoLS authorisation for reasons including the administration of medication covertly; this part of the DoLS authorisation will no longer be valid and covert administration of medication must cease immediately.

Case law9, 10 has dealt with the relationship between the use of covert medication and the need for a DoLS authorisation. A person is deprived of their liberty when they are under continuous supervision and control and are not free to leave. The administration of covert medication will only in itself lead to a deprivation of liberty where that covert medication affects the person's behaviour, mental health or it acts as a sedative to such an extent that it will deprive the person of their liberty. The use of covert medication within a care plan must be clearly identified within the DoLS assessment and authorisation.

When considering covert use of psychiatric medication the following must be considered:11

- If the patient meets the criteria for the MHA, this must be used in preference to the MCA.

- The MCA might be used to provide authority for covert medication for physical health whether or not the patient is detained under the MHA. The MCA can be used as authority for covert use of psychiatric medication in patients not under the MHA if the medication is necessary to prevent deterioration or ensure an improvement in the patient's mental health and it is in the person's best interest to receive the drug. The usual procedures for covert medication, including documentation of capacity assessment, Best Interests meeting and pharmacist's review, should be followed.

- Caution is needed in the use of medication that may sedate or reduce a patient's physical mobility, as use of such drugs may constitute a deprivation of liberty and require the patient to be under the DoLS framework. Documentation of whether the proposed use of a covert psychiatric drug constitutes a deprivation of liberty is important. Note that if a patient is found to lack capacity to consent to the admission and does not meet the criteria for detention under the MHA, DoLS should be used, so most in-patients who lack capacity to consent to medication will already be under the MHA or DoLS, although there may be some who can consent to admission but not to medication. However, even if the patient is already under the MHA or MCA as part of their admission, there still needs to be the same approach and considerations as documented here with regard to medication being given covertly.

The process for covert administration of medicines should include:

- The assurance that all efforts have been made to give medication openly in its normal form before considering covert administration.

- Assessment of capacity of the patient to make a decision regarding their treatment with medication. If the patient has capacity their wishes should be respected and covert medication not administered.

- A record of the examination of the patient's capacity must be made in the clinical notes, and evidence for incapacity documented.

- If the patient lacks capacity there should be a Best Interests meeting which should be attended by relevant health professionals and a person who can communicate the views and interests of the patient (family member, friend or independent mental capacity advocate). These meetings can be held virtually. If the patient has an attorney appointed under the MCA for health and welfare decisions then this person should be present at the meeting.

- Those attending the meeting should ascertain whether the patient has made an ‘advance decision' refusing a particular medication or treatment which can be used to guide decision-making.

- The Best Interests meeting should consider whether a formal legal procedure such as the MHA or DoLS is appropriate. Discussion of the indications and use of this legislation in the context of covert medication is outside the scope of this guidance but specialist psychiatric and/or legal opinion should be sought in individual circumstances if necessary. However, the other considerations given here - including the involvement of pharmacy, the recording of medication being given covertly on the drug chart, the dispensing nurse ensuring the covert medication is taken by the patient and regular reviews - apply for all patients, whichever legal framework is being used to give medication covertly.

- Medication should not be administered covertly until a Best Interests meeting has been held. If the situation is urgent, it is acceptable for a less formal discussion to occur between carer/nursing staff, prescriber and family/advocate in order to make an urgent decision, but a formal meeting should be arranged as soon as possible.

- After the meeting, there should be clear documentation of the outcome of the meeting. If the decision is to use covert administration of medication, a check should be made with the pharmacy to determine whether the properties of the medications are likely to be affected by crushing and/or being mixed with food or drink.12 The medication chart and electronic prescribing and medicines administration record should be amended to describe how the medication is to be administered.

- When the medication is administered in foodstuffs, it is the responsibility of the dispensing nurse to ensure that the medication is taken. This can be facilitated by direct observation or by nominating another member of the clinical team to observe the patient taking the medication.

- A plan should be made to review on a regular basis the need for continued covert administration of medicines.

- For patients in care homes, the NICE guideline ‘Managing medicines in care homes' should be referred to.13, 14 The basic principles of this NICE guidance are the same as the policy discussed in this section. Mental health practitioners have a duty to inform the care home manager if they suspect the correct procedures are not being followed as regards covert medication, and to discuss with their team leader possible safeguarding referral if the home manager does not act on their advice. The role of mental health teams supporting care homes is to support the care homes and prescriber (usually GP) in carrying out this guidance. For patients with complex mental health needs, it may be appropriate that they attend or contribute to the Best Interests meeting. However, it should be the prescriber (usually the GP), care home staff and care home pharmacist who manage the process.

- There are no specific restrictions to state that relatives or other informal carers cannot give medication covertly and in certain cases it may be acceptable as long as they have been advised to do so by a health professional (e.g. GP) and all standards of the policy have been met.

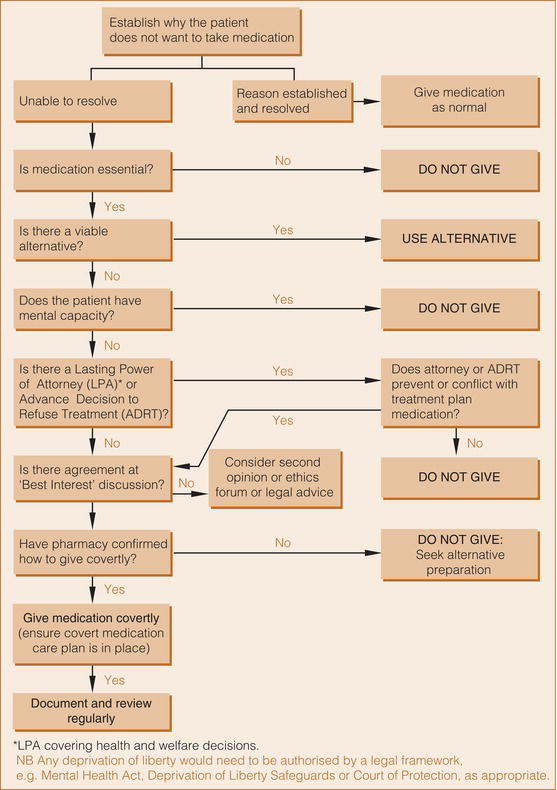

Figure provides an algorithm for determining whether or not to administer medicines covertly.