Transient tics occur in 5-20% of children. Tourette's syndrome (TS) occurs in about 0.7% of children and adolescents and is defined by persistent motor and vocal tics. As many as 65% of individuals with TS will have no tics or only very mild tics by adult life. Tics wax and wane over time and are variably exacerbated by external factors such as stress, inactivity and fatigue, depending on the individual. Tics are about two to three times more common in boys than girls.1 Functional tic disorders (involuntary physical movements, often related to anxiety) have also been described in recent years.2 These are typically seen in teenage girls.

Comorbid OCD, ADHD, ASD, depression, anxiety and behavioural problems are more prevalent than would be expected by chance, and often cause the major impairment in people with tic disorders.3 These comorbid conditions are usually treated first before assessing the level of disability caused by the tics.

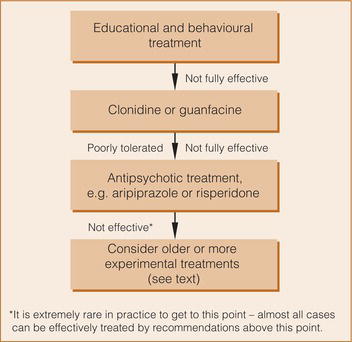

Most people with tics do not require pharmacological treatment. Education is crucial for the individual with tics, their family and the people they interact with, especially at school (Figure ). Treatment aimed primarily at reducing tics is warranted if the tics cause distress to the patient or are functionally disabling. Behavioural interventions have been found to be effective with similar effect sizes to antipsychotic medication.4, 5 Habit reversal, comprehensive behavioural intervention for tics and exposure and response prevention are the behavioural treatments of choice.6

Studies of pharmacological interventions in TS are difficult to interpret for several reasons:

- There is a large inter-individual variation in tic frequency and severity. Small, randomised studies may include patients who are very different at baseline.

- The severity of tics in a given individual varies markedly over time, making it difficult to separate drug effect from natural variation.

- The bulk of the literature consists of case reports, case series, open studies and underpowered, randomised studies. Publication bias is also likely to be an issue.

- A high proportion of patients have comorbid psychiatric illness. It can be difficult to disentangle any direct effect on tics from an effect on the comorbid illness. This makes it difficult to interpret studies that report improvements in global functioning rather than specific reductions in tics.

- Large numbers of individuals attending clinics with TS appear to use complementary or alternative therapies, with the majority reporting benefits and up to half finding these more helpful compared with medication.7 Robust research about the use of complementary or alternative therapies, their efficacy and potential adverse effects is lacking8 and certainty of evidence for their use is very low.9

Clonidine has been shown in open studies to reduce the severity and frequency of tics but in one study this effect did not seem to be convincingly larger than placebo.10 Other studies have shown more substantial reductions in tics.11, 12, 13, 14 Therapeutic doses of clonidine are in the order of 3-5mcg/kg, and the dose should be built up gradually. A transdermal patch has also shown effectiveness.15 The main adverse effects are sedation, postural hypotension and depression. Patients and their families should be informed not to stop clonidine suddenly because of the risk of rebound hypertension. Guanfacine also has some evidence of effectiveness in the treatment of tics.16, 17 The efficacy of clonidine (but not of guanfacine) was demonstrated in a 2023 systematic review and network meta-analysis of double-blind RCTs in TS which included children, adolescents and adults.9 Adrenergic α 2 agonists may also be used in children with ADHD whose tics deteriorate with stimulant medication.18

Adverse effects of antipsychotics may outweigh their beneficial effects in the treatment of tics so it is recommended that clonidine or guanfacine is generally tried first (Figure ). Antipsychotics may, however, be more effective than adrenergic α 2 agonists in alleviating tics.9

A number of first-generation antipsychotics have been used in TS. In a Cochrane review, pimozide demonstrated robust efficacy in a meta-analysis of six trials.19 In these trials, pimozide was compared with haloperidol (one trial), placebo (one trial), haloperidol and placebo (two trials) and risperidone (two trials) and was found to be more effective than placebo, as effective as risperidone and slightly less effective than haloperidol in reducing tics. It was associated with less severe adverse effects than haloperidol but did not differ from risperidone in that respect. ECG monitoring is essential for pimozide and haloperidol. Haloperidol is often poorly tolerated. Tiapride may also be effective, but evidence may not be generalisable and it has limited availability.9

SGAs, in particular aripiprazole, have in recent years been used more commonly for the treatment of TS.20 Aripiprazole is an effective and well-tolerated treatment of children with TS (and also tics21). A 10-week multicentre double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trial (N = 61) demonstrated the efficacy of aripiprazole in tic reduction in TS. Treatment was associated with significantly decreased serum prolactin concentration, increased mean body weight (by 1.6kg), body mass index and waist circumference.22 Aripiprazole was also found to be effective in another randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial (N = 133) comparing low-dose aripiprazole (5mg/day if <50kg; 10mg/day if ≥50kg), high-dose aripiprazole (10mg/day if <50kg; 20mg/day if ≥50kg) or placebo for 8 weeks.23 At week 8, tics were reduced in both the high-dose group and the low-dose group, with 69% of patients in the low-dose group and 74% in the high-dose group being very much improved or much improved, compared with 38% in the placebo group. Surprisingly, a higher proportion of children in the low-dose group (18.2%) compared with the high-dose group (9.3%) and placebo group (9.1%) gained clinically significant weight (≥7%) which may have been related to a lower average baseline weight in this group.

Several case series also support the use of aripiprazole.24, 25, 26, 27 A study evaluating the metabolic side effects of aripiprazole (N = 25) and pimozide (N = 25) in TS over a 24-month period demonstrated that treatment was not associated with significant increase in body mass index. However, pimozide treatment was associated with increases in blood glucose that did not plateau from 12 to 24 months, aripiprazole treatment was associated with increased cholesterol and both medications were associated with increased triglycerides.28 Two meta-analyses support the efficacy of aripiprazole.29, 30 One study31 suggests twice-weekly administration may be better tolerated than daily dosing. A small RCT (N = 24) comparing aripiprazole with sodium valproate in children with TS demonstrated a statistically significant difference in tic reduction favouring aripiprazole.32

Risperidone has, in addition to the studies mentioned, also been shown to be more effective than placebo in a small (N = 34) randomised study.33 Fatigue and increased appetite were problematic in the risperidone arm and a mean weight gain of 2.8kg over 8 weeks was reported. One small RCT found risperidone and clonidine to be equally effective.34 A small double-blind crossover study suggested that olanzapine 35 may be more effective than pimozide. Sulpiride has been shown to be effective and relatively well tolerated,36 as has ziprasidone. 37 Open studies support the efficacy of quetiapine 38 and olanzapine. 39, 40 One very small crossover study (N = 7) found no effect for clozapine. 41 Antipsychotic medications may not differ from each other in terms of efficacy for tics, with low to very low certainty of evidence for this comparison.9

Overall, metabolic side effects and weight gain are common with second-generation antipsychotics, even aripiprazole, so benefit/risk ratios need careful discussion.42

A small, double-blind placebo-controlled crossover trial of baclofen was suggestive of beneficial effects in overall impairment rather than a specific effect on tics.43 The numerical benefits shown in this study did not reach statistical significance. Similarly, a double-blind placebo-controlled trial of nicotine augmentation of haloperidol found beneficial effects in overall impairment rather than a specific effect on tics.44 These benefits persisted for several weeks after nicotine (in the form of patches) was withdrawn. Nicotine patches were associated with a high prevalence of nausea and vomiting (71% and 40%, respectively). The authors suggest that use as required may be appropriate. Flutamide, an antiandrogen, has been the subject of a small RCT in adults with TS. Modest, short-lived effects were seen in motor but not phonic tics.45 A small RCT showed significant advantages for metoclopramide over placebo46 and for topiramate over placebo. A meta-analysis identified 14 RCTs (all from China) comparing topiramate with haloperidol or tiapride. It concluded that owing to the overall low quality of the study designs, there is not enough evidence to support the routine use of topiramate in clinical practice.47 Tetrabenazine may be useful as an add-on treatment.48 Ecopipam, a D1 receptor antagonist, was also found to be effective in the treatment of tics in a randomised placebo-controlled crossover study including children and adolescents with TS.49 A second trial (n = 153)50 confirmed the efficacy of ecopipam. The monoamine depleting agents deutetrabenazine and valbenazine, the selective serotonin 5-HT3 receptor antagonist ondansetron and pergolide, a D1-D2-D3 agonist, are probably not effective.9, 51

Case reports or case series describing positive effects have been published for clomiphene,52 tramadol,53 ketanserin, 54 cyproterone,55 levetiracetam,56 pregabalin 57 and cannabis.58 A Cochrane review of cannabinoids concluded that there was little if any current evidence for efficacy59 and, despite a strong biological rationale for use, their overall efficacy and safety remain largely unknown.60 Many other drugs have been reported to be effective in single case reports. Patients in these reports all had comorbid psychiatric illness, making it difficult to determine the effect of these drugs on TS alone.

Botulinum toxin has been used to treat bothersome or painful focal motor tics, particularly those affecting neck muscles.42 However, a 2018 Cochrane review expressed uncertainty about its place in the treatment of tics owing to the low quality of available evidence.61

There may be a subgroup of children who develop tics and/or OCD in association with streptococcal or other infections or triggers. This group has been given (in the case of Streptococcus) the acronym PANDAS (paediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with Streptococcus)62 or, more broadly, PANS (paediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome).63 This is thought to be an autoimmune-mediated effect, and there have been trials of immune-modulatory therapy in these children as well as treatment with antibiotics for active infections and also as preventative treatment. More research in this area is warranted.