AUTHOR: Tania B. Babar, MD

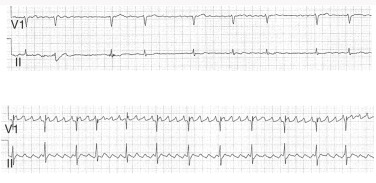

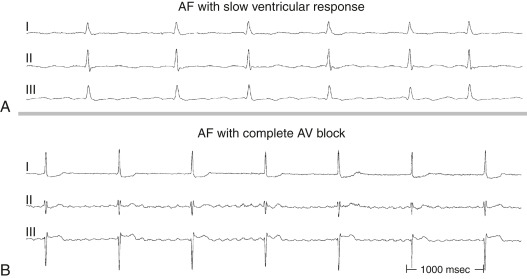

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a supraventricular tachyarrhythmia characterized by disorganized and rapid atrial activation and uncoordinated atrial contraction. AF occurs when structural and/or electrophysiologic abnormalities alter atrial tissue to promote abnormal impulse formation and/or propagation. The ventricular rate is dependent on the conduction properties of the atrioventricular (AV) node, which can be influenced by vagal/sympathetic tone, medications, or disease of the AV node.

Multiple classification schemes have been used in the past to characterize AF. The current classification scheme (divided into three major types) used by the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guideline committee is as follows:

- Paroxysmal AF: More than one episode of AF that terminate spontaneously or with intervention within 7 days

- Persistent AF: Episodes of AF that last longer than 7 days

- Permanent AF: When patient and physician decide to stop pursuing restoring sinus rhythm

- In addition to the previous AF categories, which are mainly defined by episode timing and termination, the ACC/AHA/European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines describe additional AF categories in terms of other characteristics of the patient:

- Lone atrial fibrillation (LAF): Generally refers to AF in younger patients without clinical or echocardiographic evidence of cardiopulmonary disease, diabetes, or hypertension

- Nonvalvular AF: Atrial fibrillation in the absence of moderate-to-severe mitral stenosis or in the presence of a mechanical heart valve

- Secondary AF: Occurs in the setting of a primary condition that may be the cause of the AF, such as acute myocardial infarction, cardiac surgery, pericarditis, myocarditis, hyperthyroidism, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, or other acute disease. It is considered separately because AF is less likely to recur once the precipitating condition has resolved

- Silent AF: Asymptomatic AF diagnosed by an ECG or rhythm strip

Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (PAF)

| ||||||||||||||||||||

- The prevalence of AF increases with age, from 2% in adults <65 to 9% of those >65 yr old.

- AF affects over 3 million people in the United States. AF is uncommon in infants and children and, when present, almost always occurs in association with structural heart disease.

- The incidence of AF is significantly higher in men than in women in all age groups (1.1% versus 0.8%). AF appears to be more common in whites than in blacks, who may have lower awareness of the disease.

- Stroke due to thromboembolism is the most common and dreaded complication of AF. The rate of ischemic stroke in patients with nonrheumatic AF averages 5% a yr, which is somewhere between 2 and 7× the rate of stroke in patients without AF. The risk of stroke is not due solely to AF; changes in the endothelium and elevated markers of inflammation that may contribute to thrombosis are found in patients with AF, regardless of their rhythm at the time. The attributable risk of stroke from AF is estimated to be 1.5% for those aged 50 to 59 yr, and it approaches 36% for those aged 80 to 89 yr.

- Table 1 summarizes the thromboembolic risk score.

TABLE 1 CHA2DS2-VASc Score and Associated Increased Annual Risk for Stroke

| C | Congestive heart failure | 1 |

| H | Hypertension | 1 |

| A | Age >75 yr | 1 |

| D | Diabetes | 1 |

| S | Stroke, TIA | 2 |

| V | Vascular disease | 1 |

| A | Age 65-74 yr | 1 |

| Sc | Sex (female) | 1 |

| Total score | Annual risk of stroke | |

| 0 | 0.2% | |

| 1 | 0.6% | |

| 2 | 2.2% | |

| 3 | 3.2% | |

| 4 | 4.8% | |

| 5 | 7.2% | |

| 6 | 9.7% | |

| 7 | 11.2% | |

| 8 | 10.8% | |

| 9 | 12.2% |

TIA, Transient ischemic attack.

From Warshaw G et al: Ham’s primary care geriatrics, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2022, Elsevier.

- The most frequent change in AF is the loss of atrial muscle mass and atrial fibrosis

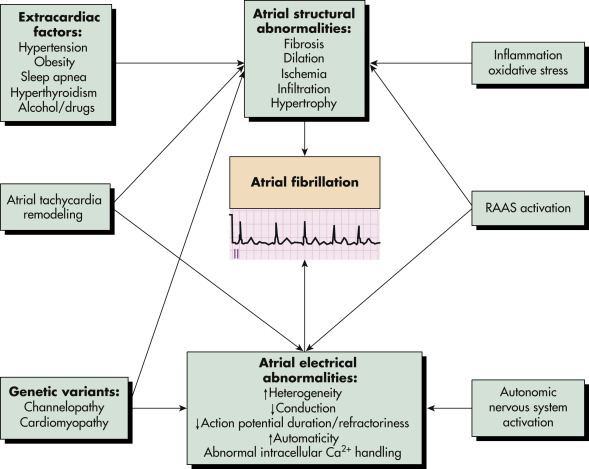

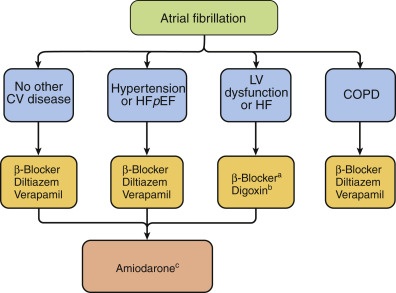

- Fibrillation is presumed to be caused by multiple wandering wavelets, usually originating from the pulmonary veins. Both reentrant and focal mechanisms have been proposed. See Fig. 1 for mechanisms of atrial fibrillation. Fig. 2 illustrates an approach to selecting drug therapy for ventricular rate control

- Vascular causes: Hypertensive heart disease

- Valvular heart disease

- Pulmonary causes: Pulmonary embolism, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obstructive sleep apnea, carbon monoxide poisoning

- Structural cardiac disease: Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, congenital heart disease (especially those that lead to atrial enlargement such as atrial septal defect)

- Pericarditis and myocarditis

- Arrhythmias: Atrial tachycardias and atrial flutters have been associated with atrial fibrillation, as has Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome

- Endocrine: Thyrotoxicosis, hyperthyroidism or subclinical hyperthyroidism, pheochromocytoma, obesity

- Surgery: Both cardiac and noncardiac

- Electrolytes: Hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia

- Systemic stress: Fever, anemia, hypoxia, sepsis, infections (e.g., pneumonia)

- Medications/toxins: Digitalis, adenosine, theophylline, amphetamines, cocaine, antihistamines, alcohol abuse and/or withdrawal, caffeine, steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (SAIDs), nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Marine omega-3 fatty acids1

- Frequency of vigorous exercise is associated with an increased risk of developing AF in young men and joggers

- Porphyrias have been associated with autonomic dysfunction and increased risk of AF

- Patients with metabolic syndrome, excessive vitamin D intake, or excessive niacin intake have a higher risk of AF

Ca2+, Ionized Calcium; RAAS, Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System.

From Parrillo JE, Dellinger RP: Critical care medicine, principles of diagnosis and management in the adult, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2019, Elsevier.

Drugs are Listed Alphabetically. A-Blockers Should Be Instituted after Stabilization of Patients with Decompensated Heart Failure (HF). The Choice of -Blocker (E.g., Cardioselective) Depends on the Patient’s Clinical Condition. Bdigoxin is Not Usually First-Line Therapy. It May Be Combined with a -Blocker and/or a Nondihydropyridine Calcium Channel Blocker When Ventricular Rate Control is Insufficient and May Be Useful in Patients with Heart Failure. Cin Part Because of Concern over its Side Effect Profile, Use of Amiodarone for Chronic Control of Ventricular Rate Should Be Reserved for Patients Who Do Not Respond to or are Intolerant of -Blockers or Nondihydropyridine Calcium Antagonists. COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; CV, Cardiovascular; HF, Heart Failure; Hfpef, Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction; LV, Left Ventricular. (From Parrillo Je, Dellinger Rp: Critical Care Medicine, Principles of Diagnosis and Management in the Adult, Ed 5, Philadelphia, 2019, Elsevier.)