AUTHOR: Fred F. Ferri, MD

DefinitionClinically significant portal hypertension is defined as a portal vein pressure >10 mm Hg, most commonly attributable to liver disease.

| ICD-10CM CODE | | K76.6 | Portal hypertension |

|

Epidemiology & Demographics

- Incidence of portal hypertension is not known.

- Cirrhosis is the most common cause of portal hypertension in the U.S.

- Portal hypertension is developed by >90% of patients with cirrhosis.

- Alcoholic and viral liver diseases are the most common causes of cirrhosis and portal hypertension in the U.S.

- Schistosomiasis is the main cause of portal hypertension outside the U.S.

- Esophageal varices may appear when portal vein pressure rises to >10 mm Hg.

- Variceal hemorrhage is the most serious complication of portal hypertension and may occur when portal pressures rise >12 mm Hg.

Physical Findings & Clinical Presentation

- Jaundice

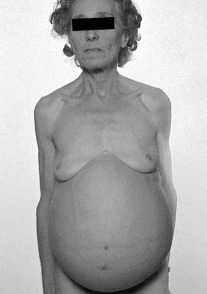

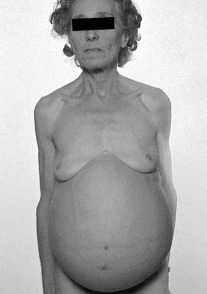

- Ascites (Fig. 1)

- Spider angiomata

- Testicular atrophy

- Gynecomastia

- Palmar erythema

- Dupuytren contracture

- Asterixis (with advanced liver failure)

- Irritability, encephalopathy

- Splenomegaly

- Dilated veins in the anterior abdominal wall

- Venous pattern on the flanks

- Caput medusae (tortuous collateral veins around the umbilicus)

- Hemorrhoids

- Hematemesis

- Melena

- Pruritus

Figure 1 Ascites secondary to portal hypertension.

Note the dilated collateral vein running up the right side of the abdomen.

From Forbes A et al [eds]: Atlas of clinical gastroenterology, ed 3, Oxford, 2005, Mosby.

EtiologyPathophysiologically caused by:

- Conditions resulting in an increased resistance to flow:

- Prehepatic (e.g., portal vein thrombosis, splenic vein thrombosis, congenital stenosis)

- Hepatic (e.g., cirrhosis, alcoholic liver disease, primary biliary cirrhosis, schistosomiasis)

- Posthepatic (e.g., Budd-Chiari syndrome, constrictive pericarditis, inferior vena cava obstruction, cor pulmonale, tricuspid regurgitation)

- Conditions leading to increase in portal blood flow:

- Splanchnic arterial vasodilation accompanying portal hypertension, mediated by local release of nitric oxide

- Arterial-portal venous fistulae

Table 1 describes the pathophysiologic changes in portal hypertension, and Table 2 summarizes the etiologies of portal hypertension.

TABLE 2 Etiology of Portal Hypertension Grouped by Location of Insult

| Site of Increased Resistance | Condition | FHVP | WHVP | HVGP | SPP |

|---|

| Presinusoidal (extrahepatic) | Extrahepatic portal, splenic, or mesenteric vein thrombosis | Normal | Normal | Normal | Increased |

| Presinusoidal (intrahepatic) | Early primary biliary cirrhosis | Normal | Normal/raised (?) | Normal/raised (?) | Increased |

| Presinusoidal (intrahepatic) | PSC | Normal | Normal/raised (?) | Normal/raised (?) | Increased |

| Presinusoidal (intrahepatic) | Sarcoid | Normal | Normal/raised (?) | Normal/raised (?) | Increased |

| Presinusoidal (intrahepatic) | Schistosomiasis | Normal | Normal/raised (?) | Normal/raised (?) | Increased |

| Presinusoidal (intrahepatic) | Congestive heart failure | Normal | Normal/raised (?) | Normal/raised (?) | Increased |

| Presinusoidal (intrahepatic) | Noncirrhotic portal fibrosis | Normal | Normal/raised (?) | Normal/raised (?) | Increased |

| Intrahepatic sinusoidal | Cirrhosis (any etiology) | Normal | Increased | Increased | Increased |

| Intrahepatic sinusoidal | Alcoholic hepatitis | Normal | Increased | Increased | Increased |

| Intrahepatic sinusoidal | Fulminant liver failure (any etiology) | Normal | Increased | Increased | Increased |

| Extrahepatic postsinusoidal hypertension | Budd-Chiari syndrome | Increased | Increased | Normal | Increased |

| Extrahepatic postsinusoidal hypertension | Constrictive pericarditis | Increased | Increased | Normal | Increased |

| Extrahepatic postsinusoidal hypertension | Inferior vena cava obstruction | Increased | Increased | Normal | Increased |

| Extrahepatic postsinusoidal hypertension | Congenital inferior vena cava web | Increased | Increased | Normal | Increased |

| Extrahepatic postsinusoidal hypertension | Right heart failure | Increased | Increased | Normal | Increased |

FHVP, Free hepatic venous pressure; HVPG, hepatic venous pressure gradient; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis; SPP, systolic pulse pressure; WHVP, wedged hepatic venous pressure.

From Vincent JL et al: Textbook of critical care, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2017, Elsevier.

TABLE 1 Pathophysiologic Changes in Portal Hypertension

| Pathophysiologic Change | Specifics |

|---|

| Hepatic resistance | |

| Passive, mechanical component: 60%-70% |

| Active, dynamic component: 30%-40% |

| Portal hypertension | |

| Shunts | |

| Splanchnic vasodilation | |

| Increased portal inflow | |

| Decrease in effective circulating volume; redistribution total blood volume | |

| Increase in endogenous vasopressors (RAA, SNS, VP) | |

| Increase in endothelin-1 |

| Angiotensin II |

| Norepinephrine |

| Vasopressin |

| PGF-2 alpha |

| Decrease in NO, CO | |

CO, Carbon monoxide; NO, nitrogen monoxide; PGF, prostaglandin; RAA, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone; SNS, sympathetic nervous system; VP, vasopressin.

From Vincent JL et al: Textbook of critical care, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2017, Elsevier.

The treatment of portal hypertension is complex and involves measures to reduce the hypertension directly, minimize volume overload, correct underlying disorders, and prevent complications (most notably SBP and variceal bleeding).

Nonpharmacologic TherapyDietary sodium restriction to generally 2000 mg/day forms the basis of therapy to limit fluid overload.

Acute General Rx

- For tense ascites, serial large-volume paracentesis (LVP) is generally recommended. The use of albumin infusion (8 to 10 g/L of ascites fluid removed) during LVP >5 L has been shown to reduce the incidence of postparacentesis circulatory dysfunction, although its use remains somewhat controversial.

- IV diuretics, typically furosemide and spironolactone, are used to achieve natriuresis and net negative salt and water balance. Renal function and serum electrolytes are monitored frequently, with transition to an oral regimen for long-term therapy.

- SBP is treated with IV antibiotics directed against enteric bacteria.

- Acute variceal hemorrhage is treated with crystalloid and blood product resuscitation, IV octreotide, terlipressin/vasopressin or somatostatin, and urgent upper endoscopy, often with sclerotherapy or band ligation. Patients with acute variceal hemorrhage should receive empiric antibiotic therapy for SBP.

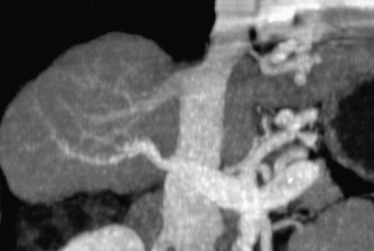

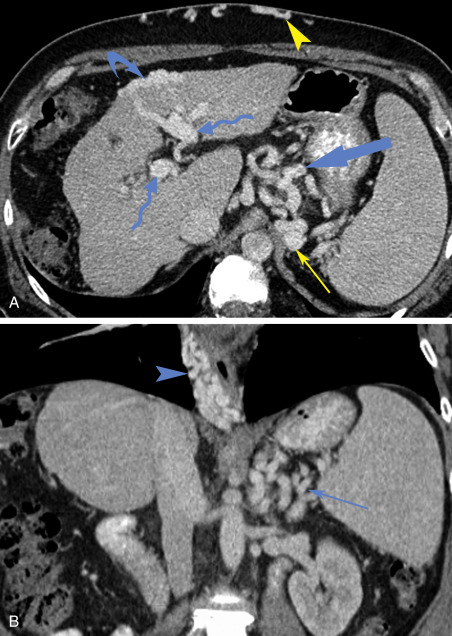

- Traditionally, a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) or surgical shunt placement may be considered in patients not responding to above measures. However, recent data show early TIPS placement improved outcomes in acute variceal hemorrhage. Table 3 summarizes indications, contraindications, and complications of the TIPS procedure.

- Table 4 compares treatment modalities for portal hypertension.

TABLE 4 Comparison of Treatment Modalities

| Treatment Modality | No (%), N = 77 | Age, Yr (Mean) | Female % | Initial Meld (Mean, Range) | Child-Pugh Score (N = 74) | Ascites Size | Death (No, %) (N = 44) | Days from Presentation Until Death or End of Study |

|---|

| Medical management | 64/77 (83%) | 52 | 23/64 (36%) | 16 (4-46) | A = 1

B = 31 | None: 6

Small: 34

Moderate: 16

Large: 8 | 40/64 (63%) | 321 ± 463 |

| TIPS | 8/77 (10%) | 56 | 5/8 (63%) | 12 (7-28) | A = 0

B = 5

C = 2 | None: 1

Small: 3

Moderate: 3

Large: 1 | 4/8 (50%) | 845 ± 407 |

| Transplant | 5/77 (7%) | 54 | 0 | 21 (10-40) | A = 1

B = 1

C = 1 | Large: 1 | 0 | 1896 ± 1752 |

TIPS, Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

From Vincent JL et al: Textbook of critical care, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2017, Elsevier.

TABLE 3 Indications, Contraindications, and Complications of the TIPS Procedure

| Indications | Relative Contraindications | Contraindications | Acute Complications | Chronic Complications |

|---|

| Upper GI bleeding | Pulmonary hypertension | Right-sided heart failure | Neck hematoma | Congestive heart failure |

| Ascites | Severe liver failure | Biliary tract obstruction | Arrhythmia | Portal vein thrombosis |

| Hepatic hydrothorax | Portal vein thrombosis | Uncontrolled infection | Stent displacement | Progressive liver failure |

| Multiple hepatic cysts | Chronic recurrent disabling hepatic encephalopathy | Hemolysis | Chronic recurrent encephalopathy |

| | Hepatocellular carcinoma involving hepatic veins | Bilhemia | Stent dysfunction |

| | | Hepatic vein obstruction | TIPSitis |

| | | Shunt thrombosis | |

| | | Hemoperitoneum | |

| | | Hemobilia | |

| | | Liver ischemia | |

| | | Cardiac failure | |

| | | Sepsis | |

GI, Gastrointestinal; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

From Vincent JL et al: Textbook of critical care, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2017, Elsevier.

Chronic Rx

- Dietary sodium restriction in combination with diuretics: The typical ratio of furosemide 40 mg to spironolactone 100 mg retains normal serum potassium levels in most patients.

- Nonselective beta-blockers (propranolol and nadolol) in dosages sufficient to reduce the resting heart rate by 25% have been shown to be effective in primary prophylaxis for first-time variceal bleeding and for preventing recurrent variceal bleeding. Dosages are usually given bid and decreased if heart rate falls to <55 beats/min or systolic blood pressure drops to <90 mm Hg. The addition of a long-acting nitrate (e.g., isosorbide-5-mononitrate) has been shown to improve portal hemodynamics. Findings of a prospective trial of beta-blockers to prevent the formation of varices were negative. The combination of beta-blockade plus endoscopic esophageal variceal banding is superior to either intervention alone.

- Intermittent LVP may be needed in “diuretic-resistant” patients.

- Patients with prior SBP merit lifelong antibiotics for secondary prevention.

- Abstinence from alcohol or treatment for hepatitis B or hepatitis C. Vaccination for hepatitis A and B as appropriate.

- Hepatic transplantation is an option in selected patients.

Disposition

- The most common complication associated with portal hypertension is variceal bleeding. The risk of bleeding from varices is approximately 15% at 1 yr.

- Development of the hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) is associated with high near-term mortality. In particular, HRS may complicate SBP, which emphasizes the importance of making the diagnosis of SBP and instituting appropriate prophylaxis.

ReferralConsultation with a gastroenterologist is recommended in all patients with portal hypertension to screen for esophageal varices.

Splanchnic arterial vasodilation is increasingly recognized as an important component of the pathophysiology of portal hypertension and ascites. There may be vasodilation in other capillary beds as well; of note, pulmonary arteriolar vasodilation can create a significant shunt fraction and resultant hypoxemia in the absence of chest radiograph or CT chest evidence of parenchymal disease. The diagnosis is suspected when otherwise unexplained hypoxia arises in a patient with cirrhosis, along with platypnea (dyspnea worse when sitting upright) and orthodeoxia (desaturation with upright posture). The diagnosis is confirmed by echocardiography with agitated saline, in which there is delayed appearance of bubbles in the left heart after injection into a peripheral vein.

CommentsPortal hypertension and its complications carry significant morbidity and mortality rates. Emphasize ethanol abstinence, provide vaccinations and prophylactic therapy where indicated, and consider early referral to a specialist for assistance with management and consideration for hepatic transplantation.