AUTHOR: Fred F. Ferri, MD

The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th edition (DSM-5), defines delirium as:

- Disturbance of consciousness with reduced ability to focus, sustain, or shift attention.

- The disturbance develops over a short period of time (usually hours to days) and tends to fluctuate during the course of a day.

- An additional disturbance in cognition (e.g., memory deficit, disorganization, language, visuospatial ability, or perception).

- A change in cognition or development of a perceptual disturbance that is not better accounted for by a preexisting, established, or evolving dementia.

- There is evidence from history, physical exam, or lab findings that the disturbance is caused by medical condition, substance intoxication or withdrawal (i.e., due to a drug of abuse or to a medication), or exposure to a toxin, or is due to multiple etiologies.

- Neuroinflammation, with increased permeability of the blood-brain barrier

- Acetylcholine deficiency

- Other neurotransmitter imbalances, including excesses of norepinephrine, serotonin, and, most important, dopamine

Hyperactive, hypoactive, and mixed subtype

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nearly 30% of older patients experience delirium at some time during the hospital course. In older surgical patients, the risk varies from 10% to 50%. Hypoactive is more common. Predisposing factors for delirium among older adults hospitalized for a medical or surgical illness are summarized in Table 1. Delirium is the most common mental disorder in patients with medical illness. Any age, race, or gender can be affected. Predisposing factors for the development of delirium during hospitalization are summarized in Table 2. Pediatric delirium is often missed but remains important because delirium is associated with longer hospital stays, decreased cognitive performance, and increased mortality. Risk factors include extremes of age, severe pain, illicit substance use, surgery, dementia, and kidney or liver failure (Table 3).

TABLE 3 Mnemonic for Risk Factors for Delirium and Agitation

| I Watch Death | Delirium | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Infection | Drugs | ||

| Withdrawal | Electrolyte and physiologic abnormalities | ||

| Acute metabolic | Lack of drugs (withdrawal) | ||

| Trauma/pain | Infection | ||

| Central nervous system pathology | Reduced sensory input (blindness, deafness) | ||

| Hypoxia | Intracranial problems (CVA, meningitis, seizure) | ||

| Deficiencies (vitamin B12, thiamine) | Urinary retention and fecal impaction | ||

| Endocrinopathies (thyroid, adrenal) | Myocardial problems (MI, arrhythmia, CHF) | ||

| Acute vascular (hypertension, shock) | |||

| Toxins/drugs | |||

| Heavy metals |

CHF, Congestive heart failure; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; MI, myocardial infarction.

From Vincent JL et al: Textbook of critical care, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2011, Saunders.

TABLE 2 Precipitating Factors for the Development of Delirium During Hospitalization for Medical or Surgical Illness

| Precipitating Factor | Odds Ratio (OR) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Use of physical restraints | 4.4 | ||

| Malnutrition | 4 | ||

| Using more than threenew medications during hospitalization | 2.9 | ||

| Use of bladder catheterization | 2.4 | ||

| Exposed to any iatrogenic event | 1.9 | ||

| Intraoperative hypotension(at least 31% drop inmean perioperative BPor a SBP ≤80 mmHg | 1.4 | ||

| Postoperative Hct <30% | 1.7 | ||

| Untreated postoperative pain | 5.4-9 | ||

| Use of anticholinergic drug | 1.5-2.7 |

BP, Blood pressure; Hct, hematocrit; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

From Warshaw G et al: Ham’s primary care geriatrics, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2022, Elsevier.

TABLE 1 Predisposing Factors for Delirium Among Older Adults Hospitalized for a Medical or a Surgical Illness

| Risk Factor | Odds Ratio (OR) Rangea | The Delirium Vulnerability Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Impairment: | 3.5-5 2-4 4 | Choose one score only 3 points 2 points 1 point |

| Current history of depression | 2-4 | 1 point |

| Current history of alcohol abuse | 3-6.5 | 2 points |

| Current and untreated hearing loss | 2 | 1 point |

| Current and untreated vision loss | 2-3.5 | 1 point |

| Need assistance in two basic activities of daily living | 2.5 | 1 point |

| Current use of anticholinergic | 1.5-2.7 | 2 points |

| Dehydration defined by BUN/creatinine >21:1 | 1.8-2 | 1 point |

| Sodium abnormality (Na <130 or Na >150) | 2-4 | 1 point |

| Vascular risk factors: history of: | 2.3 1.3-2.9 1.3 2.2 1.4 | Choose a score of 1 point if at least one risk factor was present (maximum score is also 1 point) |

| Admitted for | ||

| 3 6 | 2 points 3 points | |

| Total Points | _______ [range 0-17] | |

| Interpretation: | Risk category Low Mild Moderate Severe | Probability of developing deliriumb <5% 5%-20% 21%-40% >40% |

BUN, Blood urea nitrogen; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination.

a OR estimates were based on review of the literature.

b Delirium probability estimates for each risk category were based on a literature review and the authors’ clinical and research experiences. The delirium vulnerability scale has not been validated in a prospective cohort study.

From Warshaw G et al: Ham’s primary care geriatrics, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2022, Elsevier.

- One of the earliest symptoms is change in level of awareness and ability to focus, sustain, or shift attention. Symptoms may differ both among patients and within one patient. Family members or caregivers report that the patient “isn’t acting quite right.” Symptoms may include poor attention, sleepiness, agitation, or psychosis.

- Acuteness of presentation helps in differentiating delirium with dementia. Change in cognition, perceptual problems (such as visual, auditory, or somatosensory hallucination usually with lack of insight), memory loss, disorientation, difficulty with speech and language. It is important to ascertain from family member or caregivers the patient’s level of functioning before onset of delirium.

- Elderly patients with delirium often do not look sick, but patients with delirium are sick by definition.

- Hyperactive delirium represents only 25% of cases, with the others having hypoactive (quiet) delirium.

- There is often a prodrome phase that later blends into hypoactive delirium or erupts into an agitated confusional state.

- Physical examination should be performed, focusing on signs of infection, dehydration, or chronic disease that may be exacerbated. Vital signs are key. Consider using the Mini-Mental Status Exam or the Montreal Cognitive Assessment.

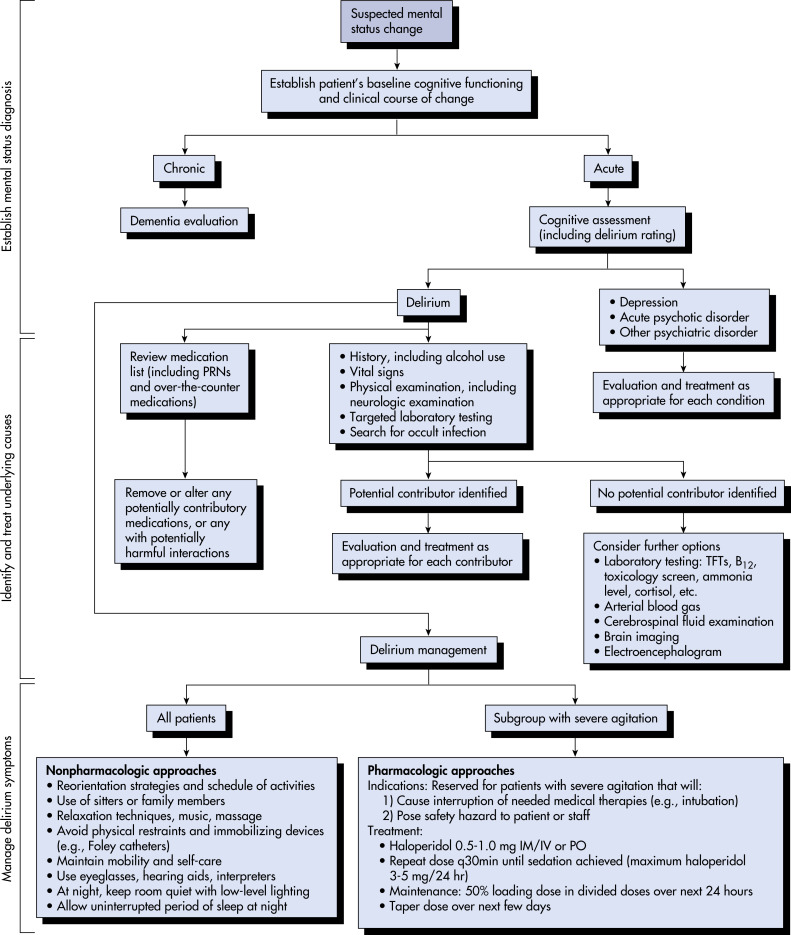

- Fig. 1 describes an algorithm for evaluation of mental status changes in an older patient.

- Table 4 summarizes delirium assessment tools.

TABLE 4 Delirium Assessment Tools

| Tool | Structure | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) | Full scale of 11 items Abbreviated algorithm targeting four cardinal symptoms | Intended for use by nonpsychiatric clinicians |

| Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) | Algorithm targeting four cardinal symptoms | Designed for use by nursing staff in the ICU |

| Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC) | 8-item screening checklist | Bedside screening tool for use by nonpsychiatric physicians or nurses in the ICU |

| Delirium Rating Scale (DRS) | Full scale of 10 items Abbreviated 7- or 8-item subscales for repeated administration | Provides data for confirmation of diagnosis and measurement of severity |

| Delirium Rating Scale-Revised-98 (DRS-R-98) | 16-item scale that can be divided into a 3-item diagnostic subscale and a 13-item severity subscale | Revision of DRS is better suited to repeat administration |

| Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale (MDAS) | 10-item severity rating scale | Grades severity of delirium once diagnosis has been made |

| Neecham Confusion Scale | 10-item rating scale | Designed for use by nursing staff and primarily validated for use in elderly populations in acute medical or nursing home setting |

ICU, Intensive care unit.

From Stern TA et al: Massachusetts General Hospital handbook of general hospital psychiatry, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2017, Elsevier.

Figure 1 Algorithm for evaluation of suspected mental status change in an older patient.

IM, Intramuscular; IV, intravenous; NG, nasogastric; PO, by mouth; PRN, as needed; TFTs, thyroid function tests.

Modified from Goldman L, Ausiello D [eds]: Cecil textbook of medicine, ed 24, Philadelphia, 2012, Saunders.

Can be multifactorial; often falls into one of the following categories (Table 5):

- Drugs: Benzodiazepines are the worst offenders, but other drugs such as narcotics, anticholinergics, beta-blockers, steroids, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, digoxin, cimetidine can cause delirium; also, withdrawal states such as alcohol withdrawal or benzodiazepine withdrawal can cause delirium

- Infection or inflammation

- Metabolic: Kidney or liver failure, thyroid, adrenal, or glucose dysregulation, anemia, vitamin deficiency such as Wernicke encephalopathy or vitamin B12 deficiency, inborn metabolic errors such as porphyrias or Wilson disease

- Stress: Surgery, sleep problems, pain, fever, hypoxia, anesthesia, environmental changes, fecal or urinary retention, burns

- Fluids, electrolytes, nutrition (FEN): Dysregulation of calcium, magnesium, potassium, or sodium; dehydration; volume overload; altered pH

- Brain disorder: CNS infection, head injury, hypertensive encephalopathy

TABLE 5 Major Causes of Delirium

| Metabolic | Electrolytes: Hypo/hypernatremia, hypo/hypercalcemia, hypo/hypermagnesemia, hypo/hyperphosphatemia Endocrine: Hypo/hyperthyroidism, hypo/hypercortisolism, hypo/hyperglycemia Cardiac encephalopathy, hepatic encephalopathy, uremic encephalopathy Hypoxia and hypercarbia Vitamin deficiencies: Vitamin B12, nicotinic acid, folic acid. Most notably Wernicke encephalopathy from thiamine deficiency Toxic and industrial exposures: Carbon monoxide, organic solvent, lead, manganese, mercury, carbon disulfide, heavy metals Porphyria | ||

| Toxic | Intoxication and overdose Serotonin syndrome Malignant neuroleptic syndrome Withdrawal: Alcohol, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, amphetamines, cocaine, coffee, phencyclidine, hallucinogens, inhalants, meperidine, and other narcotics Drugs: Anticholinergic, benzodiazepines, opiates, antihistamines, antiepileptics, muscle relaxants, dopamine agonists, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, levodopa, corticosteroids, fluoroquinolone and cephalosporin antibiotics, beta-blockers, digitalis, lithium, clozapine, tricyclic antidepressants, calcineurin inhibitors | ||

| Infectious | Urinary tract infection, pneumonia, sepsis, meningitis, encephalitis, Creutzfeldt-Jakob and other prion diseases | ||

| Neurological | Vascular: Ischemic stroke, intracerebral or subarachnoid hemorrhage, vasculitis Autoimmune and paraneoplastic encephalitides Neoplastic: Brain tumors, carcinomatous meningitis Seizure related: Postictal state, nonconvulsive status epilepticus Trauma: Concussion, subdural hematoma | ||

| Perioperative | Surgery: Thoracic (cardiac and noncardiac), vascular, and hip replacement, anesthetic and drug effects, hypoxia and anemia, hyperventilation, fluid and electrolyte disturbances, hypotension, embolism, infection or sepsis, untreated pain, fragmented sleep, sensory deprivation or overload | ||

| Miscellaneous | Hyperviscosity syndromes |

From Jankovic J et al: Bradley and Daroff’s neurology in clinical practice, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2022, Elsevier.