AUTHORS: Fahad Gul, MDand Pranav M. Patel, MD, FACC, FAHA, FSCAI

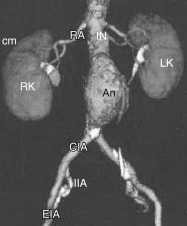

An abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a segmental full-thickness dilation of the abdominal aortic artery to at least 50% greater than the normal vessel diameter. The average diameter of a human infrarenal aorta is approximately 2 cm, thus a threshold of 3 cm is commonly considered aneurysmal.1

| ||||||||||||

- Approximately 13,000 deaths/yr in the U.S. are attributed to AAA.1

- AAA is predominantly a disease of older adults and affects men four times more than women.2

- The prevalence of AAA ranges 1.2% to 3.3% in men older than 60 yr, which is lower than had been previously reported, likely due to societal reductions in smoking. The prevalence in the U.S. specifically is unclear given that screening is rare in nonsmokers.3

- More than half of males with subaneurysmal aorta (2.6 to 2.9 cm) develop an AAA >3.0 cm within 5 yr of their original ultrasound. 28% of male patients with a subaneurysmal aorta will develop a large AAA >5.5 cm within 15 yr.4

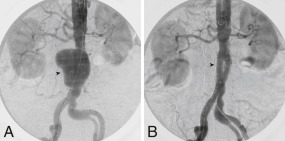

- AAAs tend to develop in the infrarenal aorta and expand at a faster rate the larger the diameter of the AAA, with each 0.5 cm increase in baseline AAA diameter increasing the rate of expansion by 0.59 mm/yr.5

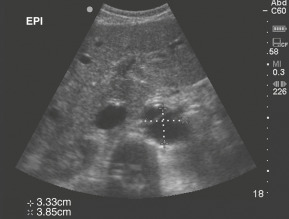

- Larger aneurysms are associated with increased rate of expansion, and thus current guidelines recommend more frequent surveillance for larger aneurysms. Frequency of surveillance for aneurysms is as follows: 3.0 to 3.9 cm every 3 yr, 4.0 to 4.9 cm every year, 5.0 to 5.4 every 6 mo.6Aneurysmal size is the greatest predictor of rupture.1

- Out of hospital AAA rupture is often lethal with mortality ranging from 80% to 90%.1,3Female sex, current smoking, and older age are associated with an increased risk of AAA rupture. Current smokers are two times more likely than former smokers to suffer from AAA rupture.3

- Annual risk for rupture of the AAA depends on the size of the AAA:1

- Heavily calcified AAAs expand at a slower rate than less calcified AAAs.6aThe presumed mechanism may be stabilization of the aortic wall by calcification.

- The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends one-time screening for AAA by ultrasonography in men ages 65 to 75 who have a history of smoking, and selectively offer men 65 yr of age or older who have never smoked but have certain risk factors, including family history of AAA in a parent or sibling. These populations have been shown to have a higher prevalence of AAA, and selectively screening this group has been shown to decrease AAA-specific mortality.3

- The USPSTF has found little benefit in repeat screening in men with a negative ultrasound and has determined that men over the age of 75 are unlikely to benefit from screening. It was also concluded that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of the harms and benefits of screening for AAA in women ages 65 to 75 who have ever smoked or with family history of AAA.3

- The Society for Vascular Surgery recommends one-time ultrasonography screening for AAAs in men and women ages 65 to 75 yr with a history of tobacco use; in men and women 65 to 75 yr with a first-degree relative with an AAA; and in patients 75 yr or older in good health who have either a history of smoking or a first-degree relative with an AAA.6

- The Society for Vascular Surgery guidelines recommend monitoring by ultrasound or CT scan should be performed every 6 mo for patients with AAAs measuring 5.0 to 5.4 cm in diameter, every 12 mo for AAAs measuring 4.0 to 4.9 cm in diameter, and every 3 yr for AAAs 3.0 to 3.9 cm in diameter.6

- Most aneurysms are asymptomatic and incidentally discovered on imaging studies.7,8

- Physical examination has moderate sensitivity for detection of AAA. Abdominal palpitation may reveal a pulsatile mass and is less than 50% sensitive in detection of AAA. Detection is further limited in individuals with abdominal girth >100 cm. Palpation of the aneurysm does not increase the risk of rupture.8

- Symptomatic patients may present with pain of the abdomen, back, flank, or groin or sequelae of the AAA’s compression of nearby organs. Early satiety, nausea, and vomiting may be caused by compression of adjacent bowel. Venous thrombosis or insufficiency may occur from iliocaval venous compression. Thromboembolization can cause lower extremity pain and discoloration. Abdominal bruits can be present in case of renal or visceral arterial stenosis. Ureteral obstruction and hydronephrosis can cause flank and groin pain and lead to obstructive renal failure.8Additionally, aneurysmal formation can lead to development of arteriovenous fistulas and aortoenteric fistulas, which may present as heart failure and gastrointestinal blood loss, respectively.8

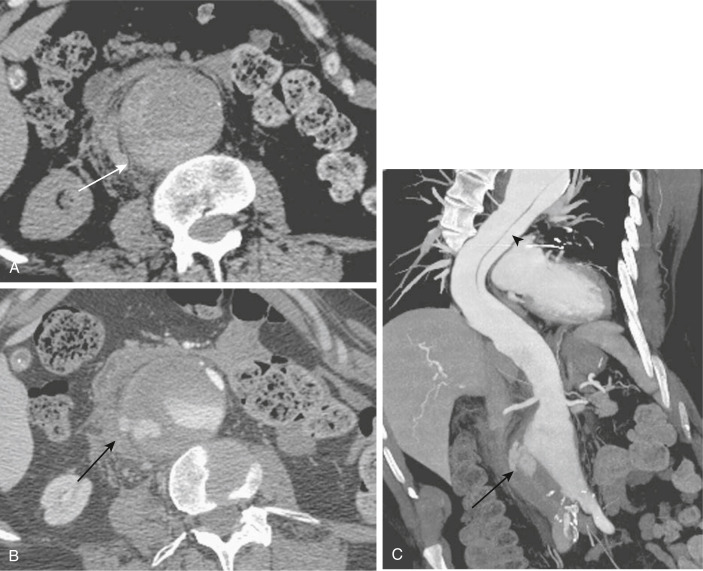

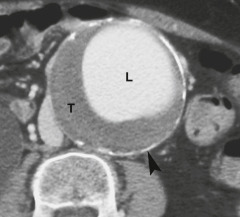

- 50% of patients with AAA rupture will classically present as a triad of abdominal or back pain, hypotension, and a pulsatile abdominal mass. Ruptured aneurysms (Fig. E1) lead to rapid progression to hemorrhagic shock and require emergent surgery within hours to increase chances of survival.1,7

- AAA development is characterised by various pathophysiological mechanisms including smooth muscle cell apoptosis and media layer thinning, vascular inflammation from lymphocyte and macrophage infiltration, and extracellular matrix degradation.1,9These degenerative processes deplete the normal lamellar elastin matrix leading to vascular remodeling and aneurysmal formation, expansion, and eventual rupture.9Matrix metalloproteinases have been implicated in the development of aneurysms as well and have been tested with variable success as a therapeutic target for prevention of AAA.10

- Advanced age is significantly associated with AAA. Individuals over the age of 65 (compared to under age 55) are 9.4 times as likely to develop AAA.2

- Smoking is considered one of the strongest modifiable risk factors for AAA development. A history of smoking was associated with an odds ratio of 5.07 for formation of AAA over 4 cm. Smoking was considered to be responsible for 75% of the excess prevalence of AAAs ≥4 cm.11

- The association of family history of AAA suggests a role of inherited connective tissues diseases such as Marfans and Ehlers-Danlos in the pathogenesis of AAA formation.2

- Less impactful risk factors include hyperlipidemia, obesity, prexisting peripheral arterial disease, cerebrovascular disease, coronary artery disease, other aneurysmal vessels, hypertension.1,2

- Regular consumption of fruits, vegetables, and nuts along with regular moderate intensity exercise were associated with reduced risk of AAA formation.2

- Ethnically, Caucasian race is associated with increased risk of AAA development compared to African American, Hispanic, and Asian origins.2