AUTHOR: Glenn G. Fort, MD, MPH

Typhoid fever is a systemic infection caused by Salmonella typhi and Salmonella paratyphi (A, B, and C).

| ||||||||||||||||

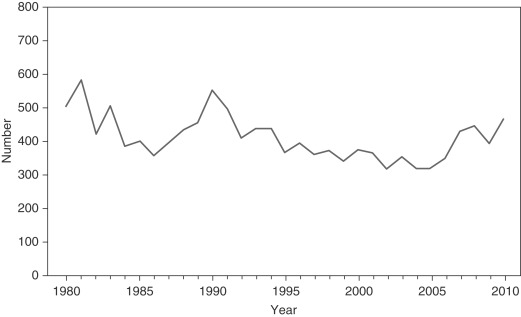

Approximately 400 cases of S. typhi infections are reported annually in the U.S. (Fig. E1). Over three quarters of the cases reported in the U.S. are now associated with foreign travel (most from Asia, Africa, and Central America).

(Table E1)

- Incubation period is 8 to 16 days.

- Usual manifestations:

- Prolonged fever (enteric fever). Temperature increases progressively and can remain elevated daily for 4 to 8 wk

- Myalgias

- Headache

- Cough

- Sore throat

- Malaise

- Anorexia, at times with abdominal pain and hepatosplenomegaly

- Diarrhea or constipation may occur early in the course of illness. One fifth of patients have constipation at diagnosis

- Rose spots, which are faint, maculopapular, blanching lesions, may sometimes be seen on the chest or abdomen

- Relative bradycardia (despite high fever) may occur.

- Moderate hepatosplenomegaly may be present.

- In an untreated patient, fever may last 1 to 2 mo. The main complication of untreated disease is GI bleeding as a result of perforation from ulceration of Peyer patches in the ileum. Mental status changes and shock are rare complications. The relapse rate is ∼10%.

TABLE E1 Clinical Features of Typhoid and Paratyphoid Fever

| Clinical Feature | Approximate Frequency (%)∗ | |

|---|---|---|

| Flulike symptoms | Fever | >95 |

| Headache | 80 | |

| Chills | 40 | |

| Cough | 30 | |

| Myalgia | 20 | |

| Arthralgia | <5 | |

| Abdominal symptoms | Anorexia | 50 |

| Abdominal pain | 30 | |

| Diarrhea | 20 | |

| Constipation | 20 | |

| Physical findings | Coated tongue | 50 |

| Hepatomegaly | 10 | |

| Splenomegaly | 10 | |

| Abdominal tenderness | 5 | |

| Rash | <5 | |

| Generalized adenopathy | <5 |

∗The proportion of patients demonstrating these clinical features of enteric fever varies depending on the time, region, and type of clinical population (hospitalized or ambulatory) assessed. Estimates are drawn from recent case series in an endemic area, with patients presenting for ambulatory or inpatient care.

From Bennett JE et al: Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2015, Saunders.

- S. typhi or S. paratyphi found only in humans

- Acquisition of disease by ingestion of food or water contaminated by human feces

- In the U.S., most cases are acquired either during foreign travel or by ingestion of food prepared by chronic carriers, many of whom acquired the organism outside of the U.S., most common in the Indian subcontinent (South, East, and Southeast Asia) and portions of sub-Saharan Africa