AUTHOR: Corey Elam Goldsmith, MD, FAAN

Idiopathic Parkinson disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative synucleinopathy defined by bradykinesia plus either resting tremor or rigidity.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- It is the second most common neurodegenerative disease worldwide and is found in every country.1

- Affects more than 1 million people in North America at 0.3% of the population and 1% of people over the age of 60. Prevalence increases with age.

- In those aged >70 yr, 700/100,000 are affected.

- Lifetime risk of PD is 2% in men and 1.3% in women.

- Prodromal symptoms during 3 yr before patients receive a diagnosis of PD include problems with working, lifting heavy objects, and balance.1a

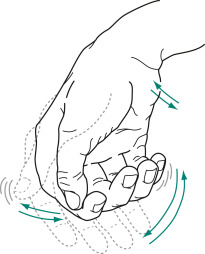

- Tremor (Figs. E1 and 2)-typically a resting tremor with a frequency of 4 to 6 Hz that is often first noted in the hand as a pill-rolling tremor (thumb and forefinger). Can also involve the leg and lip. Tremor improves with purposeful movement. Usually starts asymmetrically.

Its similarity to rolling a pill or a coin between the thumb and index finger gave rise to the description “pill-rolling” tremor. The tremor is exaggerated or sometimes apparent only when patients are anxious.

From Kaufman DM et al: Kaufman’s clinical neurology for psychiatrists, ed 9, Philadelphia, 2023, Elsevier.

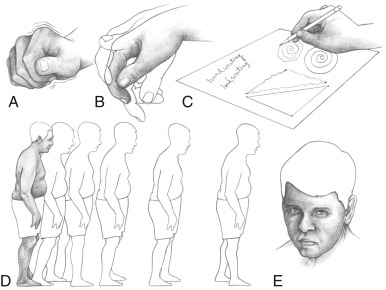

Figure E1 The parkinsonian syndrome.

A, The “pill-rolling” tremor. B, Tremor that can worsen with emotional stress. C, Handwriting abnormalities, including micrographia. D, Typical posture and gait, which becomes faster (festination). E, Lack of facial expression as well as “stare” from decreased blinking.

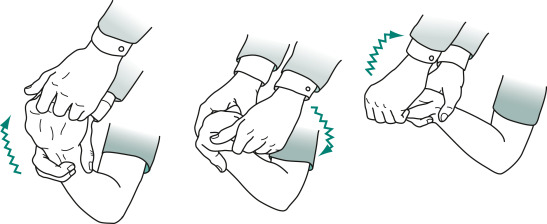

- Rigidity (Fig. E3)-increased muscle tone that persists throughout the range of passive movement of a joint. Rigidity, like resting tremor, is usually asymmetric at onset.

A superimposed tremor creates ratchet-like cogwheel rigidity.

From Kaufman DM et al: Kaufman’s clinical neurology for psychiatrists, ed 9, Philadelphia, 2023, Elsevier.

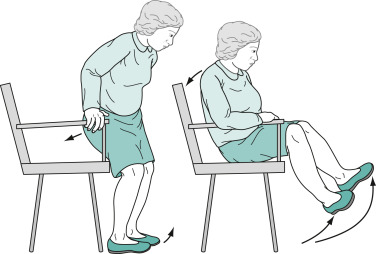

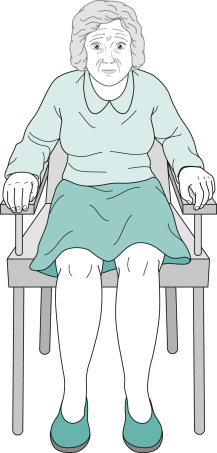

When sitting, they tend to fall slowly and solidly into a chair, and because they are unable to bend rapidly, their feet rise several inches off the floor. Sitting and turning en bloc signal early parkinsonism.

From Kaufman DM et al: Kaufman’s clinical neurology for psychiatrists, ed 9, Philadelphia, 2023, Elsevier.

- Akinesia/bradykinesia (Figs. E4 and 5)-slowness in initiating movement and decrement with repeated movements.

Their Arms Remain on the Chair or in Their Lap and Rarely Participate in Normal Gestures or Repositioning Movements. They Do Not Shift Their Weight from One Hip to Another or Make any Unnecessary Movements.

From Kaufman DM et al: Kaufman’s clinical neurology for psychiatrists, ed 9, Philadelphia, 2023, Elsevier.

- Postural instability-tested by “pull test.” Ask patient to stand in place with back to examiner. Examiner pulls patient back by the shoulders, and proper response would be to take no steps back or very few steps back without falling. Retropulsion is a positive test, as is falling straight back. Postural instability is usually mild early in the disease course but can be significant in later stages. If falls and postural reflexes are greatly impaired early on, then consider other disorders, such as progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP).

- Masked facies (hypomimia) (Fig. 6)-face seems expressionless, giving the appearance of depression. Decreased blink; often there is excess drooling.

Neurologists have Called Patients’ Facial Appearance a “stare” or “masked Facies” (Latin, Face or Countenance). Even When Subtle, the Masked Face Gives the Appearance of Apathy or Depression.

From Kaufman DM et al: Kaufman’s clinical neurology for psychiatrists, ed 9, Philadelphia, 2023, Elsevier.

- Gait disturbance.

- Stooped posture, decreased arm swing.

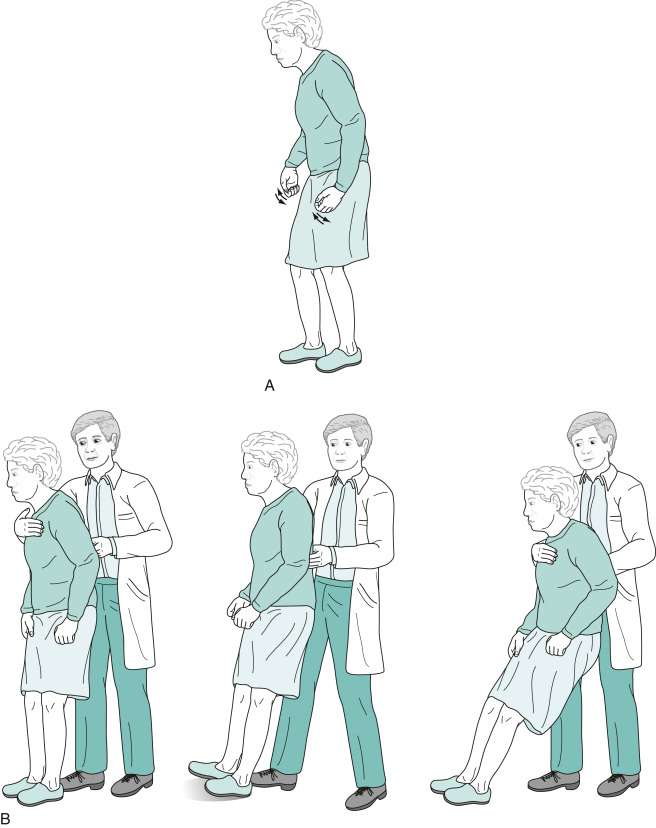

- Difficulty initiating the first step; small shuffling steps that increase in speed (festinating gait) (Fig. E7). Steps become progressively faster and shorter while the trunk inclines further forward.

Their Neck and Lower Spine, as Well as Their Limbs, are Typically Flexed. While Turning, They Simultaneously Move Their Head, Trunk, and Legs En Bloc. (B) The Pull Test Consists of the Physician's Gently, but Rapidly, Pulling the Patient's Shoulders Backward. Unaffected Individuals Will Compensate by Taking One or Two Steps Backward. Parkinson Patients, as a Sign of Impaired Postural Reflexes, Will Take Many Steps Backward (Exhibiting Retropulsion) or, in Pronounced Cases, Pitch Backwards En Bloc and Fall into the Physician’s Arms.

From Kaufman DM et al: Kaufman’s clinical neurology for psychiatrists, ed 9, Philadelphia, 2023, Elsevier.

- Other complaints and findings early on include handwriting becoming smaller (micrographia) and voice becoming softer and often “gruffer” (hypophonia).

- Nonmotor symptoms in PD include neuropsychiatric (depression, apathy, impulse control disorders, hallucinations), cognitive, dysautonomia (especially orthostatic hypotension, sexual dysfunction, and anosmia), and sensory abnormalities. These symptoms also may be subject to fluctuations during “on” vs. “off” states.

- Common premotor symptoms of PD include constipation, anosmia, depression, and REM sleep behavior disorder (Table 1).

TABLE 1 Sleep and Night Problems in Parkinson Disease and Suggested Management

| Problem | Potential Diagnosis | Proposed Management |

|---|---|---|

| Frequent Nocturia (±Two Episodes/Night) | ||

| Normal volumes | Sleep apnea syndrome | Check for sleep apnea and treat appropriately |

| Small volumes, poor stream | Prostatism | Refer to urologist |

| Small volumes, good stream | Parkinsonism: associated nocturia | Intranasal desmopressin, oral amitriptyline, or transdermal rotigotine patch; if detrusor instability: oxybutynin, tolterodine, Myrbetriq |

| Decrease evening fluid intake; empty bladder before bed; avoid evening dosing with diuretics, antihypertensives, or vasodilators; have a urinal at the bedside table | ||

| Difficulty Initiating Sleep | ||

| Early in the evening | Too early lights-off | Switch off lights later |

| Anxiety or behavioral insomnia | Sleep hygiene; treat anxiety Evening melatonin, eszopiclone, doxepin | |

| With restlessness | Restless legs syndrome | Check for low ferritin; remove antidepressant drugs; if the diagnosis is uncertain, consider polysomnography with leg monitoring; try gabapentin, pregabalin or opiates, such as tramadol, if not confused |

| Late in the night | Altered circadian cycle | Sleep hygiene; decrease levodopa/dopamine agonists in the evening Melatonin 1-2 h before the desired bedtime |

| Late in night, hypomanic | Assess for impulse control disorder | Decrease dopamine agonists; keep on levodopa monotherapy; close neuropsychologic follow-up |

| Difficulty Resuming Sleep | ||

| With cramps, muscle pain, slowness | Nocturnal bradykinesia | Immediate-release levodopa with a glass of water during awakenings Continuous drug delivery (ropinirole transdermal patch; pramipexole or extended-release ropinirole; apomorphine infusion; intrajejunal levodopa-carbidopa infusion) |

| Satin bed sheets to aid movement in bed | ||

| With restlessness | Restless legs syndrome | Similar to nocturnal bradykinesia treatment |

| With anxiety | Anxious disorder | Evening antidepressants (mirtazapine, doxepin, paroxetine) |

| With low mood | Depressive disorder | Treat the depression |

| Nightmares, Agitation | ||

| Confused at night when awake | Hallucinations, psychosis, confusion | Remove or reduce the evening dose of dopamine agonist or antidepressant; assess for sleep apnea; Antipsychotics (quetiapine, clozapine) |

| Kicks, shouts, slaps | REM sleep behavior disorders | Secure the bed environment; discontinue antidepressant; assess likelihood of sleep apnea (video-PSG before treating) Melatonin, 3-9 mg in the evening, clonazepam, 0.5-2 mg in the evening |

| Daytime Sleepiness | ||

| Falls asleep unexpectedly | Sleep attack | Check for possible sedating drugs (e.g., dopamine agonists) and remove or change them; warn patient not to drive |

| Falls asleep more often than before | Consider the Epworth Sleepiness Score; ask about associated hallucinations; consider PSG and MSLT | |

| Treat sleep apnea if severe | ||

| Decrease/stop the dopamine agonist during daytime, and other sedative drugs | ||

| Caffeine, modafinil, methylphenidate | ||

MSLT, Multiple Sleep Latency Test; PSG, polysomnography; REM, rapid eye movement.

From Kryger M et al: Principles and practice of sleep medicine, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2023, Elsevier.

- Most cases are sporadic. Age is the most common risk factor, although a combination of both environmental and genetic factors likely contributes to disease expression.

- Both pesticides and drinking well water are factors correlated with a higher incidence of PD.

- 10% to 15% have a genetic etiology. Several different genes have been identified; these include the parkin gene (a significant cause of early-onset autosomal recessive PD), LRRK2 (the most common cause of familial and sporadic parkinsonism associated with later onset of PD), and PINK1 (associated with early-onset PD).1