AUTHOR: Fred F. Ferri, MD

Impetigo is a highly contagious superficial skin infection generally caused by Staphylococcus aureus and/or Streptococcus spp.

Common presentations are bullous impetigo (generally caused by staphylococcal disease) and nonbullous impetigo (from streptococcal infection and possible staphylococcal infection); the bullous form is caused by an epidermolytic toxin produced at the site of infection.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Impetigo is the most common bacterial skin infection in children 2 to 5 yr of age. Bullous impetigo accounts for 30% of cases and nonbullous for 70% of cases. Impetigo is most common in temperate zones, mostly during the summer in hot, humid weather. Common sources for children are dirty fingers, pets, and other children in school or day care centers. Impetigo often complicates insect bites, pediculosis, scabies, eczema, and poison ivy.

- Bullous impetigo is most common in infants and children. The nonbullous form is most common in children ages 2 to 5 yr with poor hygiene in warm climates.

- The overall incidence of acute nephritis with impetigo varies between 2% and 5%.

- Nonbullous impetigo begins as a single red macule or papule that quickly becomes a vesicle. Rupture of the vesicle produces an erosion of which the contents dry to form honey-colored crusts. Multiple lesions with golden yellow crusts (Fig. E1) and weeping areas are often found on the skin around the nose, mouth, and limbs.

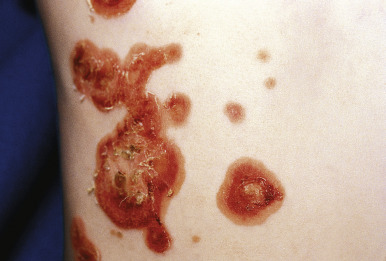

- Bullous impetigo is manifested by the presence of vesicles that enlarge rapidly to form bullae with contents that vary from clear to cloudy. There is subsequent collapse of the center of the bullae (Fig. E2); the peripheral areas may retain fluid, and a honey-colored crust may appear in the center (Figs. E3 and E4). As the lesions enlarge and become contiguous with the others, a scaling border replaces the fluid-filled rim; there is minimal erythema surrounding the lesions.

- Regional lymphadenopathy is most common with nonbullous impetigo.

- Constitutional symptoms are generally absent.