AUTHOR: Fred F. Ferri, MD

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic functional disorder manifested by alteration in bowel habits and recurrent abdominal pain and bloating. IBS is a symptom complex influenced by a variety of physiologic determinants from gut to brain and back. The ROME IV criteria for diagnosis of IBS are:

- Patient has recurrent abdominal pain ≥1 day per wk, on average, in the previous 3 mo, with an onset ≥6 mo before diagnosis.

- Abdominal pain is associated with at least two of the following three symptoms:

- Patient has none of the following warning signs:

- Age ≥50 yr, no previous colon cancer screening, and presence of symptoms

- Recent change in bowel habit

- Evidence of overt GI bleeding (e.g., melena or hematochezia)

- Nocturnal pain or passage of stool

- Unintentional weight loss

- Family history of colorectal cancer or inflammatory bowel disease

- Palpable abdominal mass or lymphadenopathy

- Evidence of iron deficiency anemia on blood testing

- Positive test for fecal occult blood

- The criteria must be fulfilled for at least the past 3 mo with symptom onset at least 6 mo before the diagnosis.

- Table 1 subtypes IBS by predominant stool pattern.

TABLE 1 Subtyping Irritable Bowel Syndrome by Predominant Stool Pattern

|

IBS, Irritable bowel syndrome.

∗Bristol Stool Form Scale 1-2 (separate hard lumps like nuts [difficult to pass] or sausage-shaped but lumpy).

† Bristol Stool Form Scale 6-7 (fluffy pieces with ragged edges, a mushy stool or watery, no solid pieces, entirely liquid).

‡ In the absence of use of antidiarrheals or laxatives.

Adapted from Sayuk GS, Gyawali CP: Irritable bowel syndrome: modern concepts and management options, Am J Med 128(8):817-827, 2015.

| ||||||||||||||||

- IBS is the most common functional bowel disorder. An estimated 15 million people in the U.S. have IBS.

- IBS occurs in 7% to 21% of the general population of industrialized countries and is responsible for >50% of gastrointestinal (GI) referrals. Worldwide adult prevalence is 12%. Incidence increases during adolescence and peaks in third and fourth decades of life.

- Female:male ratio is 2:1. Peak prevalence is from 20 to 39 yr of age.

- Nearly 50% of patients have psychiatric abnormalities, with anxiety disorders being most common.

- The clinical presentation of IBS consists of abdominal pain and abnormalities of defecation, which may include loose stools, usually after meals and in the morning, alternating with episodes of constipation.

- Physical examination is generally normal.

- Nonspecific abdominal tenderness and distention may be present.

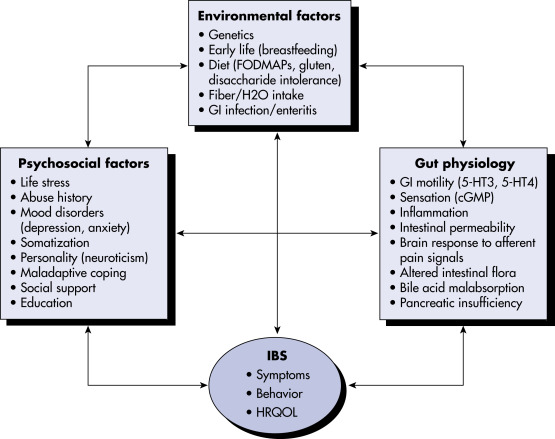

- Unknown, believed to be multifactorial. Fig. 1 illustrates a biopsychologic model of IBS pathophysiology.

- Associated pathophysiology includes altered GI motility, alteration in gut flora, and increased gut sensitivity.

- Risk factors: Anxiety, depression, personality disorders, history of childhood sexual abuse, and domestic abuse in women.

Figure 1 A biopsychosocial model of irritable bowel syndrome pathophysiology.

Irritable bowel syndrome is thought to be a multifactorial disorder, deriving from a potential multitude of etiopathogenic factors, including environmental, psychological, and physiologic factors. This model highlights the complex, often bidirectional interplay of these factors in the experience of irritable bowel syndrome symptoms. cGMP, Cyclic guanosine monophosphate; 5-HT3, serotonin type 3; 5-HT4, serotonin type 4; FODMAPS, fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols; GI, gastrointestinal; H20, water; HRQOL, health-related quality of life; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome.

Modified from Sayuk GS, Gyawali CP: Irritable bowel syndrome: modern concepts and management options, Am J Med 128(8):817-827, 2015.