AUTHORS: Benjamin J. Homer, BS and Edward J. Testa, MD and Manuel F. Dasilva, MD

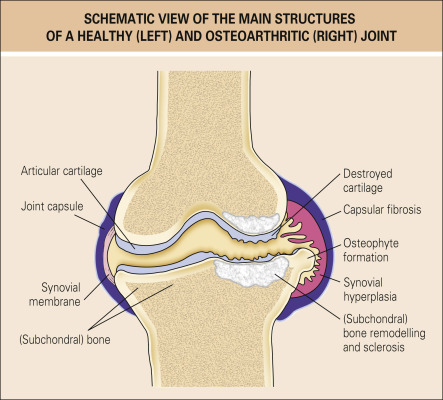

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a progressive disease of the joint representing failed repair of joint damage. It is a complex disorder involving the articular cartilage, the subchondral bone, ligaments, menisci, periarticular muscles, peripheral nerves, and synovium. The process often starts with “micro-cracks” in the articular cartilage with resultant inflammatory cascade perpetuated by the cartilage, synovium, and other joint structures. It results in pain, stiffness, and functional disability often leading to reduced health-related quality of life. Studies regarding OA-induced disability report people with OA were nearly twice as limited compared to those without OA in walking (OR = 1.9 [95% CI 1.7 to 2.2]). It also has a significant economic burden (up to 2.5% of the gross domestic product [GDP] in the U.S.) and is the leading cause of analgesic consumption and joint replacement surgeries. The American College of Rheumatology Classification criteria for osteoarthritis is described in Table E1.

TABLE E1 American College of Rheumatology Classification Criteria for Osteoarthritis

| Hip | Knee (Clinical Criteria) | Hand |

|---|---|---|

| Pain in the hip and two of the following: ESR <20 mm/h Radiographic joint space narrowing Radiographic osteophytes | Pain in the knee and five of the following: Age >50 <30 min morning stiffness Crepitus Bony enlargement Bony tenderness No synovial warmth | Pain, aching, and stiffness in the hand and three of the following: Fewer than three MCP joints swollen Hard tissue enlargement of two or more DIP joints Hard tissue enlargement of two or more of the following joints: Second and third DIP, second and third PIP, both CMC joints Deformity of at least one of the following joints: Second and third DIP, second and third PIP, both CMC joints |

CMC, Carpometacarpal; DIP, distal interphalangeal; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; MCP, metacarpophalangeal joint; PIP, proximal interphalangeal.

Modified from (1) Altman R et al: The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hand, Arthritis Rheum 33:1601-1610, 1990; (2) Altman R et al: The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hip, Arthritis Rheum 34:505-514, 1991; (3) Altman R et al: Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee, Arthritis Rheum 29:1039-1049, 1986. In Fillit HM: Brocklehurst’s textbook of geriatric medicine and gerontology, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2017, Elsevier.

Degenerative joint disease (DJD)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Prevalence and incidence estimates vary depending on the case definition and joint under consideration. In North America and Europe, OA of the hand, knee, and hip is reported in roughly 60%, 33%, and 5% of adults 65 yr and older, respectively, with these prevalence rates rising with age.1

Prior to age 50, there is minimal gender discrepancy. After age 50, there is increased incidence of OA in females compared to males.

Occurs more frequently after 50 yr of age, but recent data suggest onset can occur as early as age 30.

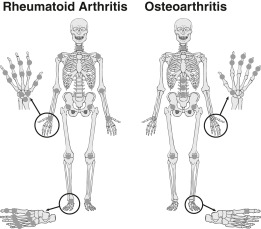

Osteoarthritis is considered predominantly a mechanical noninflammatory form of arthritis (Fig. E1). OA is thought to be the result of hostile biomechanics on an already susceptible joint (Fig. E2).2 Risk factors may be classified as either local or systemic. Local or biomechanical factors include obesity leading to increased load on the articular cartilage, mechanical environment of the joint (includes deformities like pes planus, genu varus and valgus, proprioception at the joint), local joint activity/occupation (textile worker leading to hand OA, high-impact runners leading to knee OA), and muscle weakness (quadriceps weakness leading to knee OA). Other deformities, such as femoro-acetabular impingement and limb length inequality, can confer significant risk of developing end-stage OA. Systemic risk factors include nutritional factors such as antioxidant and vitamin D deficiency, hormonal status, high bone mineral density, and genetics (candidate genes being evaluated include IGF-1 gene, cartilage oligomeric protein gene, vitamin D receptor gene). That said, there is no concrete evidence showing that preventing the disease or reducing disease progression can be achieved by supplemental vitamin D, antioxidants, or estrogen. Obesity also increases the susceptibility of developing osteoarthritis via systemic adipokines.3

Courtesy of E. Bartnik, Frankfurt, Germany. In Hochberg MC: Rheumatology, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2019, Elsevier.

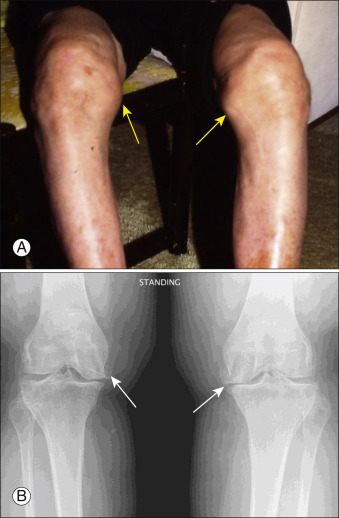

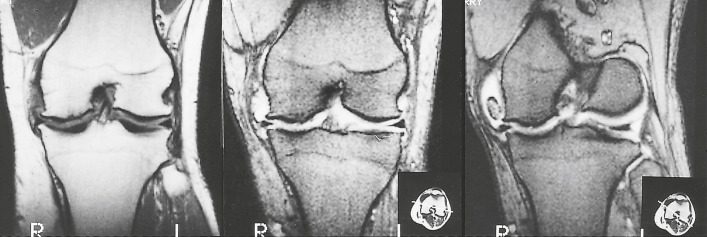

Figure E2 Osteoarthritis (OA) of the knees.

A, Bony prominences caused by osteophytes at the medial joint margins are visible to inspection (arrows). B, Radiographic appearance of medial osteophytes (arrows). Also characteristic of OA, there is asymmetric narrowing of the joint space; in this case, the medial compartments (adjacent to the arrows) are more narrowed than the lateral compartments.

From Hochberg MC: Rheumatology, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2019, Elsevier.

- Similar symptoms in most forms: Pain generally with activity, stiffness, or gelling (generally short-lived and morning stiffness lasting less than 30 min), crepitus

- Loss of function in joints (e.g., loss of dexterity in patients with hand osteoarthritis, with or without significant pain)

- Joint tenderness (Fig. E3), swelling

- Crepitus with motion, pain with range of motion

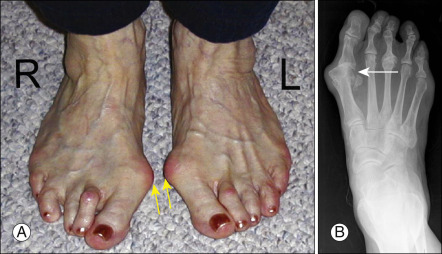

- Bouchard and Heberden nodes (bony enlargement of the proximal interphalangeal [PIP] and distal interphalangeal [DIP] joints of the hand, respectively) (Fig. E4)

There is Bilateral Enlargement of the First MTP Joint (Arrows), with Medial Subluxation of the Phalanx (Bunion), as Well as Relaxation of the Transtarsal Ligament, with Medial Subluxation of the MTP and Bony Enlargement of the Fifth MTP Joints (Tailor Bunion, Bunionette). B, Radiographic Appearance of First MTP OA with Bunion (Arrow).

From Hochberg MC: Rheumatology, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2019, Elsevier.

(Heberden nodes: Posterior lateral swelling of the distal interphalangeal joints. Bouchard nodes: Posterior lateral swelling of the proximal interphalangeal joints.)

From Fillit HM: Brocklehurst’s textbook of geriatric medicine and gerontology, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2017, Elsevier.

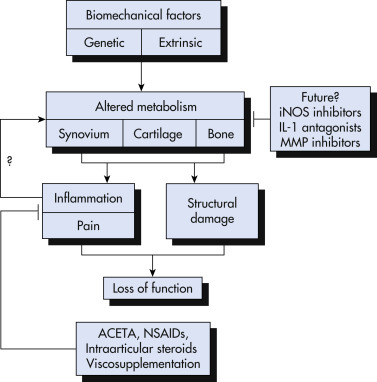

Osteoarthritis is most often primary or idiopathic and can be monoarticular, oligoarticular, or poly-ar-tic-u-lar. Secondary OA is due to an identifiable condition such as trauma, mechanical abnormalities, or congenital disorders (Fig. E5). Risk factors for osteoarthritis are summarized in Table E2. Inflammatory arthritis, crystal deposition diseases, metabolic disorders, Paget disease of bone, and osteonecrosis may also contribute to the development of secondary OA.

Figure E5 Multiple factors that predispose to, initiate, and perpetuate osteoarthritis.

In the future, structure-modifying treatments will be targeted to the biochemical processes that promote disease progression. ACETA, Acetaminophen; IL-1, interleukin-1; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase, NSAIDs, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs.

From Firestein GS et al: Firestein & Kelley’s textbook of rheumatology, ed 11, Philadelphia, 2021, Elsevier.

TABLE E2 Risk Factors for Osteoarthritis

| Host Factors | Environmental Factors | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic factors | Familial clustering has also been found at the hip and knee | Biomechanics | Repetitive ergonomic and biomechanical demands may create joint stresses leading to OA Hemiparesis associated with reduction of expression of OA in the affected limb and overexpression in the remaining functional limb Chopstick use associated with OA of the IP joint of the thumb, second and third MCP, and PIP joints |

| Age | The strongest identifiable risk factor | Trauma | Injuries to the joint, such as dislocations, fractures, ligament ruptures, and meniscal tears |

| Gender | The age association is strongest in women: Possibly a hormonal influence Hand OA has a peak incidence in menopausal women | ||

| Hormones | Controversial Hand OA has a peak in menopausal women; however, the Chingford and Framingham studies suggested estrogen has protective effect | ||

| Bone mineral density | Negative relationship between bone mineral density and OA at some sites | ||

| BMI | Obesity is strongly associated with the incidence of knee OA Hand OA likely to be related to biomechanical factors | ||

| Joint alignment | Varus deformity of the knee is associated with progressive OA, as is varus/valgus ligamentous instability at the knee joint Developmental problems leading to altered joint biomechanics such as congenital dysplasias | ||

BMI, Body mass index; IP, interphalangeal; MCP, metacarpophalangeal joint; OA, osteoarthritis; PIP, proximal interphalangeal.

Modified from Fillit HM: Brocklehurst’s textbook of geriatric medicine and gerontology, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2017, Elsevier.

TABLE E4 Treatment of Osteoarthritis

| Treatment Method | Evidence | Recommendation Levela |

|---|---|---|

| Weight loss (if patient is overweight or obese) | Effective and safe | LOE = D, Expert opinion |

| Exercise | Effective for pain and function, especially in supervised setting Effect depends on sustainability of land-based exercise program, so home exercise programs following physical therapy are suggested Discuss fall prevention, balance training, and safety with graduated physical activity | Core part of treatment |

| Brace/splinting | May be effective | Limited evidence |

| Tai Chi, Yoga, Qi Gong | Variable efficacy, safe, limited by access | Limited evidence |

| Acupuncture | Variable efficacy, depends on individual offering the services | Limited evidence |

| Safe, limited by access | ||

| Acetaminophen (APAP) (up to 4 g/day) | Efficacy for symptom relief is small compared to oral NSAIDs but better safety profile, daily cumulative dose <3-4 g | Limited evidence |

| Non-aspirin NSAIDs for OA of the hand, knee, and hip | Although efficacy is smaller, topical NSAIDs are preferred over oral NSAIDs because of the gastrointestinal, renal, and cardiovascular adverse effects of oral NSAIDs. Use lowest effective dose for shortest duration. If duration of use >2 wk suggest gastric mucosa protection. | LOE = D, High consensus, conditional |

| Intraarticular steroids | Moderate efficacy with improvement in pain and function in the short term | LOE = D, High consensus, conditional |

| Intraarticular viscosupplementation | Efficacy is small and clinically not meaningful. Potential for postinjection reactions (usually effusion) leading to ED visits17 | LOE = D, Low consensus, conditional |

| Glucosamine | Safe but not effective | LOE = D, Low consensus |

| Topical analgesics (capsaicin, lidocaine) | Safe but questionable efficacy | LOE = D, Low consensus |

| Opioids, including tramadol | Not effective and several adverse effects | LOE = D, Low consensus |

ED, Emergency department; LOE, level of evidence; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, OA, osteoarthritis. Total knee arthroplasty and total hip replacement Effective in select surgical candidate, best before severe functional impairments

a Based on OARSI treatment guideline 2019 for nonsurgical treatment of osteoarthritis. The variability for the site of OA (knee, hip, and hand), lack of placebo-controlled group (especially for studies on exercise), and small size of random control trials make it complex.

From Warshaw G et al: Ham’s primary care geriatrics, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2022, Elsevier.

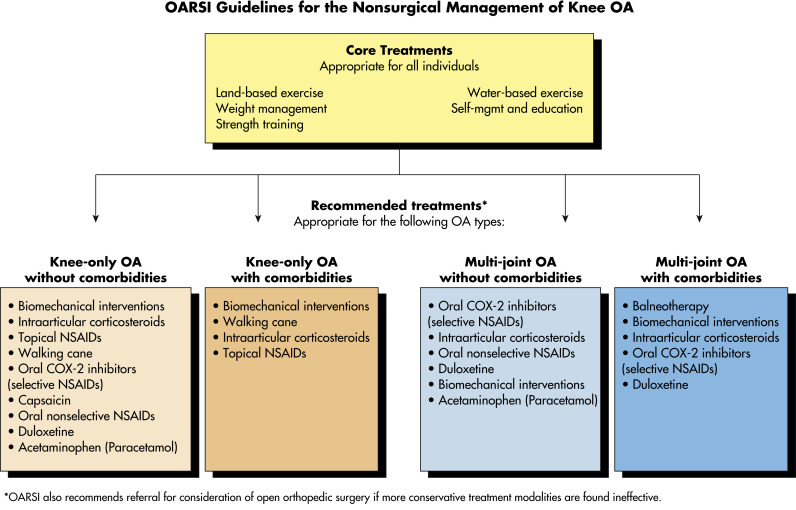

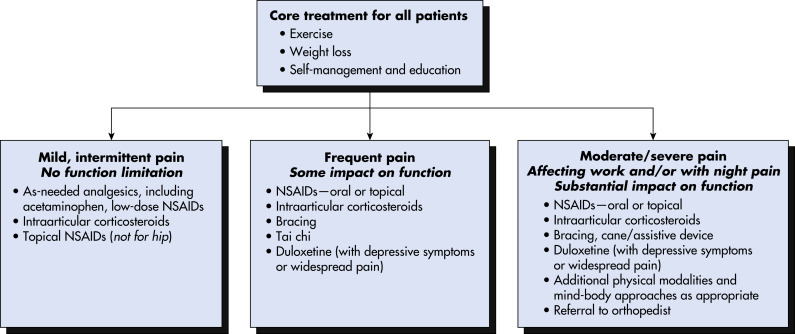

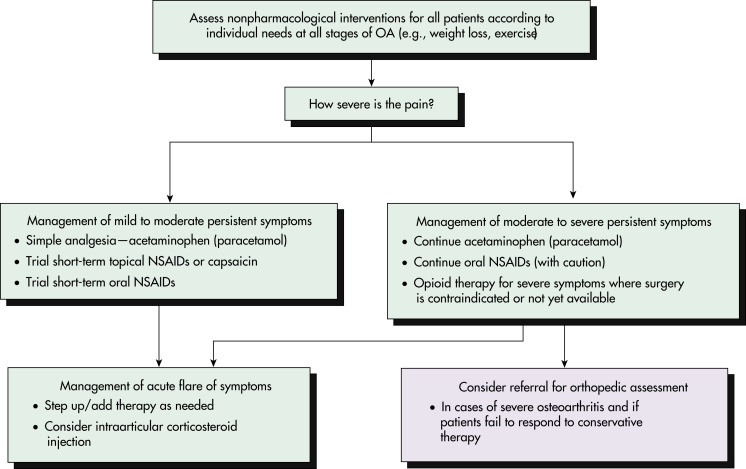

- Optimal use of both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic measures (Fig. E10) yields best outcome

- Education and reassurance

Figure E10 Appropriate treatments summary.

COX-2, Cyclooxygenase-2; NSAID, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug; OA, osteoarthritis; OARSI, Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

From McAlindon TE et al: OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis, Osteoarthritis Cartilage 22:363-388, 2014.