AUTHOR: David J. Lucier Jr, MD, MBA, MPH

- Acute pancreatitis is an inflammatory process of the pancreas with intrapancreatic activation of enzymes that may also involve peripancreatic tissue and/or remote organ systems. The diagnosis of acute pancreatitis requires at least two of the following criteria: Serum amylase or lipase ≥3 times normal, abdominal pain consistent with pancreatitis, and radiographic findings (CT or MRI) of acute pancreatitis.

- The Ranson scoring system for acute pancreatitis is described in Boxes 1 and 2.

- The Revised Atlanta Criteria (Box 3) uses early prognostic signs, organ failure, and local complications to define disease severity:

- Mild pancreatitis: No organ failure, no local or systemic complications, pancreatitis typically resolves in first week

- Moderate pancreatitis: Transient organ failure (≤48 h) or local complications (e.g., pancreatic necrosis, peripancreatic fluid collections, peripancreatic necrosis) or exacerbation of comorbid disease

- Severe pancreatitis: Persistent organ failure (>48 h)

- The BALI Score evaluates only four variables:

- These measurements are taken at admission and at 48 h. Mortality is >25% for a score of 3 and exceeds 50% with a score of 4.

- Severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) is diagnosed by the presence of any of the following four criteria:

- Organ failure with one or more of the following: Shock (systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg), pulmonary insufficiency (PaO2≤60 mm Hg), renal failure (serum creatinine >2 mg/dl after rehydration), and gastrointestinal bleeding (>500 ml/24 h)

- Local complications such as necrosis, pseudocyst, or abscess

- At least three of the Ranson criteria (see Boxes 1 and 2) or

- At least eight of the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) criteria

Box 3 Atlanta Criteria for Acute Pancreatitis

From Townsend CM et al: Sabiston textbook of surgery, ed 21, St Louis, 2022, Elsevier.

Box 1 Ranson Prognostic Criteria for Nongallstone Pancreatitis

|

From Townsend CM et al: Sabiston textbook of surgery, ed 21, St Louis, 2022, Elsevier.

Box 2 Ranson Prognostic Criteria for Gallstone Pancreatitis

|

From Townsend CM et al: Sabiston textbook of surgery, ed 21, St Louis, 2022, Elsevier.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- The incidence of pancreatitis is increasing in the U.S. Admissions for acute pancreatitis have increased dramatically, and acute pancreatitis was the number-one GI-related cause for admission across U.S. hospitals in 2012. There are >270,000 cases of acute pancreatitis reported annually in the U.S., with 40%+ resulting from gallstone disease (most common cause) and 30% caused by alcohol consumption.

- Incidence in urban areas is twice that of rural areas (20/100,000 persons in urban areas).

- 20% of patients have necrotizing pancreatitis; the remainder have interstitial, or edematous, pancreatitis.

- Drugs are responsible for less than 5% of all cases of acute pancreatitis.

- Epigastric tenderness and guarding, often radiating to the back; pain usually developing suddenly, reaching peak intensity within 10 to 30 min, severe and lasting several hours without relief. Rarely, some patients can have painless severe pancreatitis

- Nausea and vomiting (up to 90% of cases)

- Hypoactive bowel sounds (from ileus)

- Tachycardia, shock (from decreased intravascular volume)

- Confusion (from metabolic disturbances)

- Fever (SIRS response or infection when pancreatic necrosis is present)

- Decreased breath sounds (pleural effusions) or rales (atelectasis, acute respiratory distress syndrome [ARDS])

- Jaundice (from obstruction or compression of biliary tract)

- Ascites (from tear in pancreatic duct, leaking pseudocyst)

- Palpable abdominal mass (pseudocyst, phlegmon, abscess, carcinoma)

- Evidence of hypocalcemia (Chvostek sign, Trousseau sign)

- Evidence of retroperitoneal bleeding (hemorrhagic pancreatitis):

- Tender subcutaneous nodules (caused by subcutaneous fat necrosis)

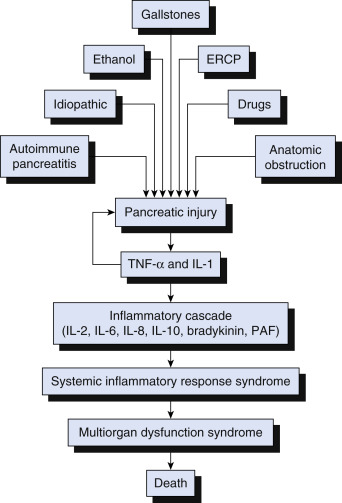

- The most common causes of acute pancreatitis are gallstones (40% of cases) and excessive alcohol consumption (30% of cases). Alcohol-related pancreatitis is most common after long term (>10 yr of heavy drinking). The pathophysiology of severe acute pancreatitis is illustrated in Fig. 1

- Hypertriglyceridemia (usually >1000 mg/dl) from any cause

- Drugs (e.g., thiazides, furosemide, corticosteroids, tetracycline, estrogens, valproic acid, metronidazole, azathioprine, methyldopa, pentamidine, ethacrynic acid, procainamide, amiodarone, sulindac, nitrofurantoin, ACE inhibitors, danazol, cimetidine, piroxicam, gold, ranitidine, sulfasalazine, isoniazid, acetaminophen, cisplatin, didanosine, opiates, erythromycin, metformin, GLP-1 receptor agonists, incretin mimetics)

- Abdominal trauma

- Surgery

- Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), especially with manipulation of the pancreatic duct

- Infections (predominantly viral)

- Peptic ulcer (penetrating duodenal ulcer)

- Pancreas divisum (congenital failure to fuse of dorsal or ventral pancreas)

- Idiopathic

- Pregnancy

- Vascular (vasculitis, ischemic)

- Hypercalcemia

- Pancreatic carcinoma (primary or metastatic)

- Renal failure

- Hereditary pancreatitis, such as in patients with cystic fibrosis

- Immunoglobulin G subclass 4 (IgG4) disease

- Occupational exposure to chemicals: Methanol, cobalt, zinc, mercuric chloride, creosol, lead, organophosphates, chlorinated naphthalenes

- Others: Scorpion venom, obstruction at ampulla region (neoplasm, duodenal diverticula, Crohn disease, rarely celiac disease), hypotensive shock, autoimmune pancreatitis

- Causes of acute pancreatitis in pediatric patients are summarized in Table E1

Figure 1 Pathophysiology of severe acute pancreatitis.

The local injury induces the release of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-1 (IL-1). Both cytokines produce further pancreatic injury and amplify the inflammatory response by inducing the release of other inflammatory mediators, which cause distant organ injury. This abnormal inflammatory response is responsible for the mortality seen during the early phase of acute pancreatitis. ERCP, Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; PAF, platelet-activating factor.

From Townsend CM et al: Sabiston textbook of surgery, ed 21, St Louis 2022, Elsevier.

TABLE E1 Causes of Acute Pancreatitis in Children

| Obstructive | |||

| Cholelithiasis and biliary sludge | |||

| Choledochal cyst | |||

| Pancreas divisum | |||

| Anomalous junction of biliary and pancreatic ducts | |||

| Annular pancreas | |||

| Ampullary obstruction (mass, inflammation from Crohn disease) | |||

| Ascaris infection | |||

| Medications and Toxins | |||

| l-asparaginase | |||

| Valproic acid | |||

| Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine | |||

| Didanosine | |||

| Pentamidine | |||

| Tetracycline | |||

| Opiates | |||

| Mesalamine | |||

| Sulfasalazine | |||

| Alcohol | |||

| Cannabis | |||

| Systemic Diseases | |||

| Inflammatory bowel disease | |||

| Hemolytic uremic syndrome | |||

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | |||

| Collagen vascular disease | |||

| Kawasaki disease | |||

| Shock | |||

| Sickle cell disease | |||

| Infectious | |||

| Sepsis | |||

| Mumps | |||

| Coxsackievirus | |||

| Cytomegalovirus | |||

| Varicella-zoster | |||

| Herpes simplex | |||

| Mycoplasma | |||

| Ascaris | |||

| Genetic | |||

| Cystic fibrosis-CFTR mutations | |||

| Hereditary pancreatitis-SPINK, PRSS1, and CTRC mutations | |||

| Other | |||

| Trauma | |||

| Hyperlipidemia | |||

| Hypercalcemia | |||

| Autoimmune |

From Marcdante KJ et al: Nelson essentials of pediatrics, ed 9, Philadelphia, 2023, Elsevier.