AUTHOR: Fred F. Ferri, MD

Obesity refers to having an excess amount of body fat in relation to lean body mass, or a body mass index (BMI) of ≥30 kg/m2. Overweight is defined as BMI of 25 to 29.9 kg/m2, and morbid obesity refers to adults with a BMI ≥40 kg/m2. BMI is used as a surrogate measure of obesity. Weight classification by BMI is summarized in Table 1. Abdominal obesity is defined as waist circumference >102 cm (40 in) in men and >88 cm (35 in) in women.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 1 Weight Classification by BMI

| Weight Classification | Obesity Class | BMI (kg/m2) | Risk of Obesity-Related Diseases | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europeans | Asians | |||

| Underweight | <18.5 | <17.5 | Increased | |

| Normal weight | 18.5-24.9 | 17.5-22.9 | Normal | |

| Overweight | 25.0-29.9 | 23.0-27.4 | Increased | |

| Obesity | I | 30.0-34.9 | 27.5-32.4 | High |

| II | 35.0-39.9 | 32.5-37.5 | Very high | |

| Extreme obesity (polysarcia) | III | ≥40.0 | ≥37.5 | Extremely high |

BMI, Body mass index.

From Melmed S et al: Williams textbook of endocrinology, ed 14, Philadelphia, 2020, Elsevier.

- The World Health Organization first recognized obesity as a worldwide epidemic in 1997. As of 2005, 1.6 billion adults worldwide were classified as overweight, 400 million of whom were obese. It is predicted that the combination of overweight and obesity will soon eclipse public health issues such as malnutrition and infectious diseases as the most significant cause of poor health.

- Worldwide, data from the Global Burden of Disease Study from 1980 to 2013 indicate the prevalence of adult obesity has increased from 28.8% to 36.9% in men and 29.8% to 38% in women. The prevalence of childhood and adolescent obesity has also substantially increased.

- Based on U.S. NHANES data from 2011 to 2012, the prevalence of abdominal obesity was 54%. It is estimated that by 2023, 2 in every 5 adults and 1 in every 4 children in the U.S. will be categorized as obese.

- Obesity is the most common health problem in women of reproductive age. Obesity before pregnancy is disproportionately prevalent among women who identify as American Indian and Alaska Native (40%), non-Hispanic Black (39%), or Hispanic (32%), as compared with those who identify as non-Hispanic White (26%) or non-Hispanic Asian (10%).1

- The present cost of obesity in the U.S. population is estimated at $100 billion annually. Approximately two thirds of people living in the U.S. are overweight, which is the highest percentage in the world.

- For persons with a BMI ≥30 kg/m2, all-cause mortality is increased by 50% to 100% above that of persons with BMI in the range of 20 to 25 kg/m2.

- Obesity is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cancer (particularly colon, prostate, breast, and gynecologic malignancies), sleep apnea, degenerative joint disease, thromboembolic disorders, digestive tract diseases (gallstones), and dermatologic disorders.

- Significant morbidity and risk of death are projected to begin in young adulthood, resulting in >100,000 excess cases of coronary heart disease (CHD) by 2035, even with the most modest projection of future obesity.

- When children enter kindergarten, 12.4% are obese, and another 14.9% are overweight. Data show that incident obesity between the ages of 5 and 14 yr is more likely to have occurred at younger ages.2

- Obesity in adolescence is significantly associated with increased risk of incident severe obesity in adulthood, with variations by sex and race/ethnicity. Overweight or obese adults who were obese as children have increased risk of type 2 DM, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and carotid artery atherosclerosis.

- Obesity is a major preventable cause of death and disability in the U.S. (the other is tobacco).

- Extensive data indicate that weight loss can reverse or arrest the harmful effects of obesity.

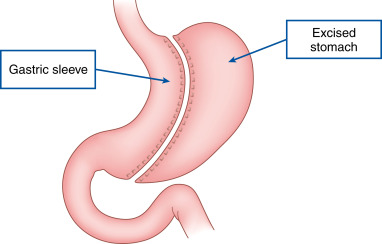

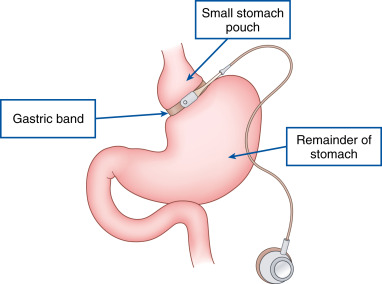

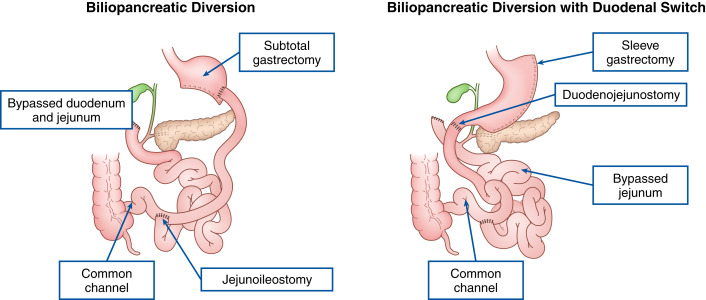

- In 2013 nearly 180,000 bariatric surgery procedures were performed in the U.S. Of these procedures 42% were laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, 34% were Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and 15% were laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding.

- Physical examination should assess the degree and distribution of body fat, signs of secondary causes of obesity, and obesity-related comorbidities.

- Increased waist circumference is apparent. Excess abdominal fat is clinically defined as a waist circumference >40 in (>102 cm) in men and >35 in (>88 cm) in women (in Asian men and women, >36 in and >33 in, respectively). Central obesity is a risk factor for mortality even among individuals with normal BMIs.

- Symptoms associated with hypertension, coronary artery disease (CAD), and diabetes (e.g., polyuria, polydipsia, acanthosis nigricans, retinopathy, and neuropathy) may be present.

- Obesity is associated with cardiac hypertrophy, diastolic dysfunction, and decreased aortic compliance, which are independent predictors of cardiovascular risk.

- Joint pain and swelling are associated with degenerative joint disease secondary to obesity.

- The physical exam and ECG often underestimate the presence and extent of cardiac dysfunction in obese patients. Jugular venous distention and hepatojugular reflux may not be seen, and heart sounds are frequently distant.

- A large quantity of fluid is present in the interstitial space of adipose tissue, as the interstitial space is ∼10% of the tissue wet weight. This excess fluid in this compartment, if redistributed into the circulation, can have negative repercussions in obese individuals with heart failure. Obese individuals have higher cardiac output and a lower total peripheral resistance than do lean individuals, and obesity is associated with persistence of elevated cardiac filling pressure during exercise.

- Obesity predisposes to heart failure through several different mechanisms: Increased total blood volume, increased cardiac output, left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, and adipositas cordis (excessive epicardial fat and fatty infiltration of the myocardium).

- The pathophysiology of obesity is complex and poorly understood, but includes social, nutritional, physiologic, psychological, and genetic factors (Table 2).

- Environmental factors such as a sedentary lifestyle and chronic ingestion of excess calories can cause obesity.

- Obesity may be related to genetic factors, which are thought to be polygenic. Genetic studies with adopted children have demonstrated that they have similar BMIs to their biologic parents but not their adoptive parents. Twin studies also demonstrate a genetic influence on BMI.

- Secondary causes of obesity can result from medications (antipsychotics, steroids, and protease inhibitors being common ones) and neuroendocrine disorders (like Cushing syndrome and hypothyroidism).

- Box 1 summarizes medical conditions associated with severe obesity.

BOX 1 Medical Conditions Associated With Severe Obesity

From Townsend CM et al: Sabiston textbook of surgery, ed 21, St Louis, 2022, Elsevier.

TABLE 2 Gene Mutations Associated With Obesity

| Gene | Effect | Action on | Inheritance | Linked To |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leptin/leptin receptor | Appetite stimulant | Hypothalamus | Autosomal recessive | Severe childhood obesity |

| Ghrelin receptor | Appetite stimulant | Hypothalamus | Autosomal recessive | Short stature and obesity |

| Melanocortin 4 receptor | Appetite inhibitor | Hypothalamus | Autosomal dominant | Increased fat mass, insulin resistance |

| Proopiomelanocortin (POMC) | Appetite inhibitor | Melanocortin 4 receptor in hypothalamus | Autosomal recessive | Severe early onset obesity by age 1 and excessive eating caused by insatiable hunger |

| Neuropeptide Y (NPY) | Appetite stimulant | Hypothalamus | Autosomal recessive | Hypertension, high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, increased food intake and hunger |

From Townsend CM et al: Sabiston textbook of surgery, ed 21, St Louis, 2022, Elsevier.