AUTHOR: Fred F. Ferri, MD

DefinitionPolycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is characterized by an accumulation of incompletely developed follicles in the ovaries due to anovulation and associated with ovarian androgen production. In its complete form, it is associated with polycystic ovaries, amenorrhea, hirsutism, and obesity. Table 1 describes criteria for a diagnosis of PCOS.

TABLE 1 Criteria for Diagnosis of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

| Study∗ | Criteria |

|---|

| National Institute of Child Health and Human Development 1990 | Menstrual irregularity

Hyperandrogenism (clinical or biochemical) |

| ESHRE-ASRM 2003 Rotterdam criteria | Menstrual irregularity

Hyperandrogenism (clinical or biochemical)

Polycystic ovaries on ultrasound (two of three required) |

| AEPCOS Society 2006 | Hyperandrogenism (clinical or biochemical) and menstrual irregularity

Polycystic ovaries on ultrasound (either or both of the latter two) |

| NIH Workshop 2012 | Endorsement of Rotterdam criteria, acknowledging its limitations, and suggesting the name PCOS should be changed |

AEPCOS, Androgen Excess and PCOS; ASRM, American Society for Reproductive Medicine; ESHRE, European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology; NIH, National Institutes of Health; PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome.

From Gershenson DM et al: Comprehensive gynecology, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2022, Elsevier.

SynonymsPolycystic ovarian syndrome

Stein-Leventhal syndrome

PCOS

| ICD-10CM CODE | | E28.2 | Polycystic ovarian syndrome |

|

Epidemiology & Demographics

- 6% to 25% of reproductive-age women (most common endocrine disorder in this population).

- Symptoms usually begin around the time of menarche, and the diagnosis is often made during adolescence or young adulthood.

- Increased risk of endometrial and ovarian cancers.

- PCOS is the most common cause of anovulatory infertility.

Physical Findings & Clinical Presentation

- Oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea

- Dysfunctional uterine bleeding

- Infertility

- Hirsutism

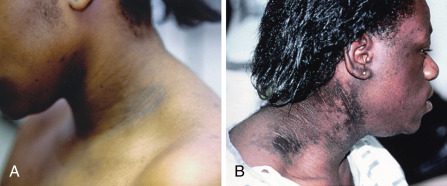

- Acne, alopecia, acanthosis nigricans (Fig. E1)

Figure E1 Acanthosis nigricans.

A, Moderate acanthosis nigricans (i.e., darkening and thickening of skin) at the lateral lower fold of the neck. Notice facial hirsutism (sideburns) in the same patient. B, Severe acanthosis nigricans in another patient with severe insulin resistance.

B, Courtesy Dr. R. Ann Word, Dallas, Texas. From Melmed S et al: Williams textbook of endocrinology, ed 12, Philadelphia, 2011, Saunders.

- Obesity (40% only), predominantly abdominal obesity

- Insulin resistance (type 2 diabetes mellitus)

- Hypertension

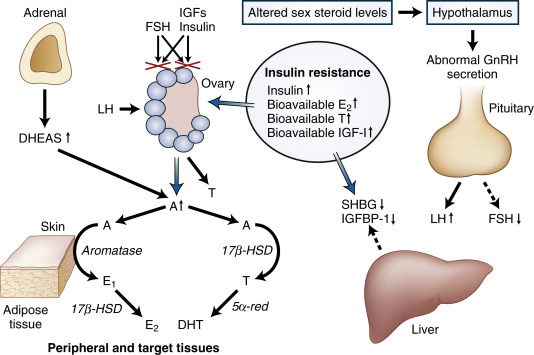

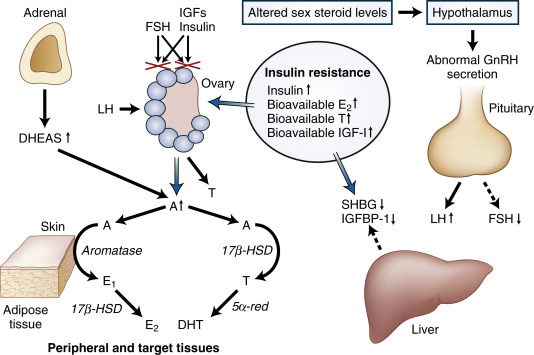

Etiology & PathogenesisElevated serum luteinizing hormone (LH) concentrations and an increased serum LH/follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) ratio result either from an increased gonadotropin-releasing hormone hypothalamic secretion or less likely from a primary pituitary abnormality. This results in dysregulation of androgen secretion and increased intraovarian androgen, the effect of which in the ovary is follicular atresia, maturation arrest, polycystic ovaries, and anovulation. Hyperinsulinemia is a contributing factor to ovarian hyperandrogenism, independent of LH excess. A role for insulin growth factor (IGF) receptors has been postulated for the association of PCOS and diabetes. Fig. E2 illustrates the pathologic mechanisms in PCOS.

Figure E2 Pathologic mechanisms in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

A deficient in vivo response of the ovarian follicle to physiologic quantities of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), possibly because of an impaired interaction between signaling pathways associated with FSH and insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) or insulin, may be an important defect responsible for anovulation in PCOS. Insulin resistance associated with increased circulating and tissue levels of insulin and bioavailable estradiol (E2), testosterone (T), and IGF1 gives rise to abnormal hormone production in a number of tissues. Oversecretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) and decreased output of FSH by the pituitary, decreased production of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) and IGF-binding protein 1 (IGFBP-1) in the liver, increased adrenal secretion of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), and increased ovarian secretion of androstenedione (A) all contribute to the feed-forward cycle that maintains anovulation and androgen excess in PCOS. Excessive amounts of E2 and T arise primarily from the conversion of A in peripheral and target tissues. T is converted to the potent steroids estradiol or DHT (dihydrotestosterone). Reductive 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17β-HSD) enzyme activity may be conferred by protein products of several genes with overlapping functions; 5α-reductase (5α-red) is encoded by at least two genes, and aromatase is encoded by a single gene. GnRH, Gonadotropin-releasing hormone.

From Melmed S et al: Williams textbook of endocrinology, ed 12, Philadelphia, 2011, Saunders.

Treatment (Table 3)

Treatment (Table 3)The goal is to interrupt the self-perpetuating abnormal hormone cycle:

- Reduction of ovarian androgen secretion by laparoscopic ovarian wedge resection. Laparoscopic ovarian surgery (laparoscopic ovarian drilling [LOD]) is a useful alternative that does not trigger ovarian hyperstimulation.

- Reduction of ovarian androgen secretion by using oral contraceptives or LH-releasing hormone (LHRH) analogs.

- Weight reduction for all obese women with PCOS. Loss of abdominal fat seems to be crucial to restore ovulation.

- FSH stimulation with clomiphene HMG or pulsatile LHRH.

- Urofollitropin (pure FSH) administration.

- Metformin improves ovulation, insulin sensitivity, and possibly hyperandrogenemia.

TABLE 3 Treatment for Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

| Complaint | Treatment Options |

|---|

| Infertility | Letrozole, clomiphene, with or without metformin, gonadotropins, ovarian cautery (“drilling”) |

| Skin manifestations | Oral contraceptive + antiandrogen (spironolactone, finasteride), GnRH agonists |

| Abnormal bleeding | Cyclic progestogen, oral contraceptives |

| Weight, metabolic concerns | Diet/lifestyle management, metformin |

From Gershenson DM et al: Comprehensive gynecology, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2022, Elsevier.

Choice of treatment:

- The management of hirsutism without risking pregnancy includes oral contraceptives, glucocorticoids, LHRH analogs, or spironolactone (an antiandrogen). Finasteride and flutamide may be similarly effective in reducing hirsutism as spironolactone.

- Pregnancy can be achieved with clomiphene (alone or with glucocorticoids, human chorionic gonadotropin, or bromocriptine), HMG, urofollitropin, pulsatile LHRH, or ovarian wedge resection. Metformin may also induce ovulation. Recent trials comparing the aromatase inhibitor letrozole to clomiphene for infertility have shown higher live-birth and ovulation among infertile women with PCOS treated with letrozole. When considering in vitro fertilization (IVF), the transfer of fresh embryos is generally preferred over the transfer of frozen embryos; however, a recent trial among infertile women with PCOS undergoing IVF revealed that frozen-embryo transfer is associated with a higher rate of live birth, a lower risk of the ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, and a higher risk of preeclampsia after the first transfer than with fresh-embryo transfer.

- Psychologic screening for depression is recommended. Women with PCOS are fourfold more likely to have abnormal depression scores.

The diagnosis of PCOS excludes secondary causes (androgen-producing neoplasm, hyperprolactinemia, adult-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia).

Clinical:

- The symptoms, signs, and biochemical features of PCOS vary greatly among women and may change over time.

- PCOS is the most common cause of chronic anovulation with estrogen present. A positive progesterone withdrawal test establishes the presence of estrogen. Medroxyprogesterone (Provera) 10 mg qd is administered for 5 days and bleeding occurs if estrogen is present.

- The presence of oligomenorrhea, hirsutism, obesity, and documented polycystic ovaries establishes the diagnosis.

Differential DiagnosisCauses of amenorrhea:

- Primary (unusual in PCOS):

- Genetic disorder (Turner syndrome)

- Anatomic abnormality (e.g., imperforate hymen)

- Secondary:

- Pregnancy

- Functional (cause unknown, anorexia nervosa, stress, excessive exercise, hyperthyroidism, less commonly hypothyroidism, adrenal dysfunction, pituitary dysfunction, severe systemic illness, drugs such as oral contraceptives, estrogens, or dopamine agonists)

- Abnormalities of the genital tract (uterine tumor, endometrial scarring, ovarian tumor)

Laboratory Tests

- Glucose tolerance test at the initial presentation and every 2 yr thereafter (rule out diabetes mellitus). Impaired glucose tolerance is very common, occurring in approximately 30% of women with PCOS

- Fasting lipid panel (rule out dyslipidemia), alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase (rule out hepatic steatosis)

- Elevated LH/FSH ratio >2.5

- Prolactin level elevation in 25%

- Elevated androgens (testosterone [free and total levels], DHEA-S) (rule out androgen-secreting tumor)

- Other: Thyroid-stimulating hormone (rule out hypothyroidism), 17-hydroxyprogesterone (rule out congenital adrenal hyperplasia), 24-h urine for cortisol and creatinine (rule out Cushing syndrome)

- TSH

- Table 2 summarizes laboratory testing to exclude other causes of ovulatory dysfunction and hyperandrogenism

TABLE 2 Laboratory Testing to Exclude Other Causes of Ovulatory Dysfunction and Hyperandrogenism

| Lab | Evaluation for: | Comment |

|---|

| Total and/or bioavailable testosterone | Androgen-secreting tumor | Measure if there are symptoms concerning for an androgen-secreting tumor or if biochemical evidence of hyperandrogenism is needed to make the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome. Rapid progression or a total testosterone >200 ng/dl should prompt a workup for an androgen-secreting tumor. |

| Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate | Androgen-secreting tumor | Measure if there are symptoms concerning for an androgen-secreting tumor. Although modest elevations in dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate can be seen in polycystic ovary syndrome, rapid progression or greater elevations should prompt a workup for an adrenal androgen-secreting tumor. |

| Morning 17-hydroxyprogesterone | Late-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia | This disorder is caused by a partial adrenal enzyme defect that leads to impaired cortisol production, compensatory elevation in adrenocorticotropic hormone, and subsequent excess androgen production. Symptoms may mimic polycystic ovary syndrome. Normal values <200 ng/dl. If higher than this, adrenocorticotropic hormone stimulation test recommended. |

| 24-h urine for cortisol and creatinine; dexamethasone suppression test; salivary cortisol | Cushing syndrome | Consider ruling out Cushing syndrome in women with an abrupt change in menstrual pattern, later-onset hirsutism, or other evidence of cortisol excess such as hypertension, facial plethora, supraclavicular fullness, hyperpigmented striae, and fragile skin. |

| Prolactin | Hyperprolactinemia | May be accompanied by galactorrhea. Consider ruling this out in all women with irregular menstrual cycles. |

| Thyroid function studies | Hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism | Consider ruling out thyroid dysfunction in all women with irregular menstrual cycles. |

From Setji TL, Brown AJ: Polycystic ovary syndrome: update on diagnosis and treatment, Am J Med 127:912-919, 2014.

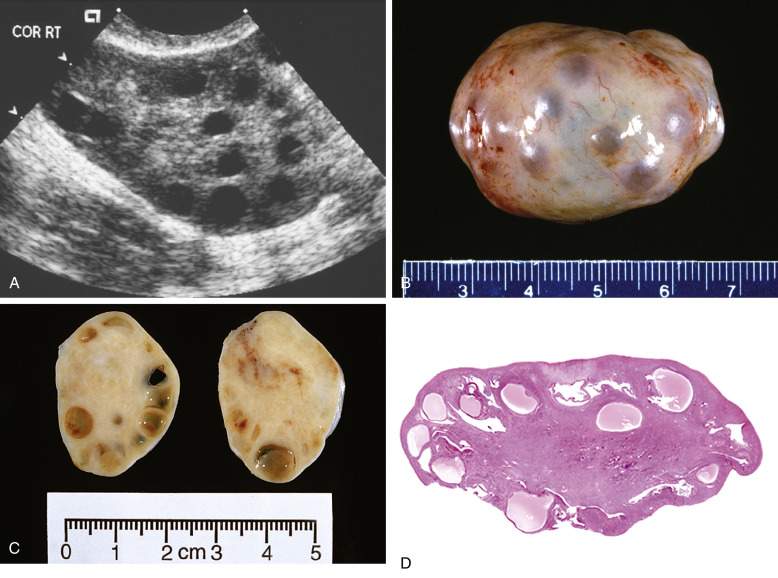

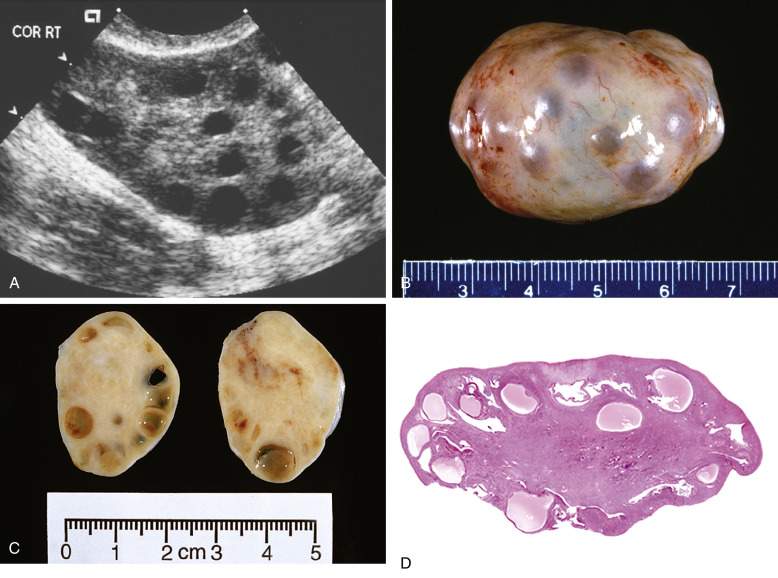

Imaging StudiesPelvic ultrasound (Fig. E3) reveals the presence of twofold to fivefold ovarian enlargement with a thickened tunica albuginea, thecal hyperplasia, and 20 or more subcapsular follicles from 1 to 15 mm in diameter. It is important to note that having polycystic ovaries alone does not make the diagnosis of PCOS because 20% of women with polycystic ovaries have no symptoms.

Figure E3 A, Ultrasonography of Polycystic Ovaries Depicting Numerous CystsB, Gross Appearance of Polycystic Ovaries. Numerous Follicles Can Be Appreciated Beneath the Capsule. C, Cross Section of B Illustrates Subcortical Cystic Follicles. D, Low-Power Microphotograph Exhibits Combination of Cystic Follicles and Fibrotic Ovarian Cortex.

From Crum CP et al: Diagnostic gynecologic and obstetric pathology, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2018, Elsevier.

DispositionTable 4 summarizes metabolic complications in PCOS. Cardiovascular risk factors associated with PCOS are described in Table 5.

TABLE 5 Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

| Risk Factor | Features |

|---|

| Traditional risk factors | Obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, abnormal homocysteine, C-reactive protein, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, increase in inflammatory adipocytokines such as TNF-α, decrease in adiponectin; higher prevalence of diabetes, hypertension |

| Atherosclerosis | Coronary catheterization studies, increase in carotid intima-media thickness, coronary calcium |

| Endothelial dysfunction by blood flow studies | All increased in classic PCOS; less of a concern with milder phenotypes using Rotterdam criteria |

PCOS, Polycystic ovary syndrome; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

From Gershenson DM et al: Comprehensive gynecology, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2022, Elsevier.

TABLE 4 Metabolic Complications in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

| Abnormal glucose tolerance (impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes) | 30% of obese polycystic ovary syndrome women have impaired glucose tolerance, and 10% have type 2 diabetes by age 40. In thin women with polycystic ovary syndrome, 10% have impaired glucose tolerance, and 1.5% have type 2 diabetes. |

| Obesity | Prevalence of obesity varies considerably in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Previously, prevalence rates of obesity were estimated based on populations of women with polycystic ovary syndrome seeking care. A recent study comparing patients presenting for care in a polycystic ovary syndrome clinic with an unselected population evaluated during a preemployment physical suggests that obesity and overweight may not be more common in polycystic ovary syndrome. In that study, 63.7% of polycystic ovary syndrome clinic patients were obese, compared with 28% of unselected women with polycystic ovary syndrome identified during screening, and 28% of nonpolycystic ovary syndrome controls. Polycystic ovary syndrome symptoms, including hyperandrogenism and oligo-ovulation, are exacerbated by obesity. |

| Metabolic syndrome | 33%-50% of U.S. women with polycystic ovary syndrome have metabolic syndrome compared to only 12% in a similarly aged National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey population. In contrast, only 8.2% of women with polycystic ovary syndrome in Italy met criteria for metabolic syndrome. Thus, metabolic syndrome varies by geographic location, a finding likely related to different body mass index, though other causes including genetics and diet could also be playing a part. |

| High blood pressure | Data have been conflicting, but a large Kaiser Permanente study demonstrated that hypertension or elevated blood pressure was more than twice as common in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (27% vs. 12%). |

| Dyslipidemia | Dyslipidemia is more prevalent in women with polycystic ovary syndrome compared to controls (15% vs. 6%). In a meta-analysis, triglyceride values were 26 mg/dl higher (95% CI 17-35), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol was 12 mg/dl higher (95% CI 10-16), and high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol was 6 mg/dl lower (95% CI 4-9) in women with polycystic ovary syndrome compared with controls. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome also have higher concentrations and proportions of small, dense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. |

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis | Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis have recently been recognized as a potential complication in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Prevalence of fatty liver disease in polycystic ovary syndrome women has been estimated to be 15%-55%, depending on the diagnostic parameter used (level of serum alanine aminotransferase or ultrasound). Individuals that may be at higher risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease including nonalcoholic steatohepatitis include those with metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and possibly hyperandrogenemia. |

| Cardiovascular disease | Many studies demonstrate abnormal surrogate markers of cardiovascular disease in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. However, data regarding cardiovascular disease risk are conflicting with some studies suggesting an increased risk in women with polycystic ovary syndrome, whereas other studies have not found this difference in cardiovascular risk. While it is important to recognize and treat cardiovascular risk factors in this population, further research of cardiovascular risk and complications is still needed to clarify the long-term risk. |

CI, Confidence interval.

From Setji TL, Brown AJ: Polycystic ovary syndrome: update on diagnosis and treatment, Am J Med 127:912-919, 2014.