AUTHOR: Narges Alipanah-Lechner, MD

Aspiration pneumonia refers to pulmonary infection of the lower airways and lung parenchyma resulting from entry of colonized oropharyngeal or upper gastrointestinal contents.1 Aspiration pneumonia is considered part of the continuum that also includes community- and hospital-acquired pneumonias.1 Chemical pneumonitis (or aspiration pneumonitis) refers to lung injury and inflammation resulting from entry of sterile substances toxic to the lower airways.

- Symptoms develop within hours to a few days after aspiration event, though anaerobic infections can have a more subacute pre-sentation.

- Clinical presentation ranges from minimal symptoms to fulminant respiratory failure.

- Symptoms can include dyspnea, diffuse wheeze, cough, hypoxia, tachypnea, tachycardia, sputum production, and fever.

- Lung exam may demonstrate wheezes, crackles, or rhonchi.

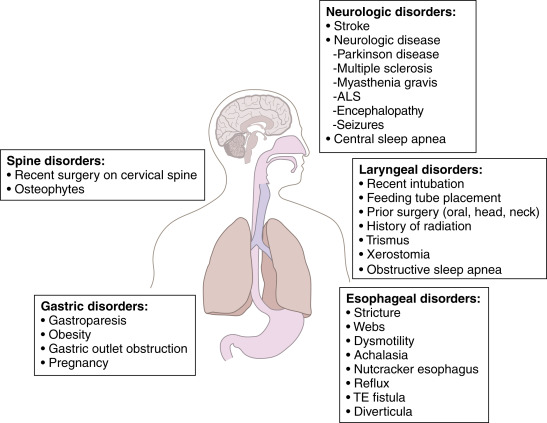

Complex interaction of etiologies, ranging from chemical (often acid) pneumonitis after aspiration of sterile gastric contents (generally not requiring antibiotic treatment) to bacterial aspiration. Risk factors for aspiration pneumonia include vomiting, decreased consciousness, poor dentition, ineffective cough reflex or glottic closure, and gastroesophageal reflux disease.4-11Table 1 and Fig. E1 summarize risk factors for aspiration pneumonia.

TABLE 1 Risk Factors for Dysphagia and Aspiration Pneumonia

| Cerebrovascular disease | |||

| Ischemic stroke | |||

| Hemorrhagic stroke | |||

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | |||

| Degenerative neurologic disease | |||

| Alzheimer disease | |||

| Multiinfarct dementia | |||

| Parkinson disease | |||

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (motor neuron disease) | |||

| Multiple sclerosis | |||

| Head and neck cancer | |||

| Oropharyngeal malignancy | |||

| Oral cavity malignancy | |||

| Esophageal malignancy | |||

| Other | |||

| Scleroderma | |||

| Diabetic gastroparesis | |||

| Reflux esophagitis | |||

| Presbyesophagus | |||

| Achalasia |

From Vincent JL et al: Textbook of critical care, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2017, Elsevier.

Figure E1 Risk factors for aspiration.

ALS, Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; TE, tracheoesophageal.

From Broaddus VC et al: Murray & Nadel’s textbook of respiratory medicine, ed 7, Philadelphia 2022, Elsevier.

- Most patients have a mixed infection with aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. The most common bacteria are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, and Enterobacteriaceae.12-14 Anaerobes (Peptostreptococcus, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Fusobacterium necrophorum, Prevotella, and Bacteroides species) are less frequently isolated.15

- High-risk groups: age >65 yr; alcohol use; IV drug use; altered mental status; stroke victims; cardiac arrest; and patients with esophageal disorders, seizures, periodontal disease, or recent dental manipulations.4-11

- Causative organisms:

- Anaerobes listed above, although in many studies gram-negative aerobes (60%) and gram-positive aerobes (20%) predominate13,16-18

- E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus including MRSA, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Serratia, Proteus spp., H. influenzae, S. pneumoniae, Legionella, and Acinetobacter spp. (sporadic pneumonias) in two thirds of cases

- Fungi, including Candida albicans, in <1%19

- High-risk groups: Seriously ill hospitalized patients (especially patients with coma, acidosis, alcohol use disorder, uremia, diabetes mellitus, nasogastric intubation, or recent antimicrobial therapy), who are frequently colonized with aerobic gram-negative rods; patients undergoing anesthesia; those with strokes, dementia, or swallowing disorders; patients >65 yr; and those receiving antacids or H2 blockers, or proton pump inhibitors (but not sucralfate).

- Hypoxic patients receiving concentrated O2 have diminished ciliary activity, increasing risk for aspiration pneumonia.