AUTHOR: Harlan G. Rich, MD, FACP, AGAF

A Mallory-Weiss tear (MWT) is a longitudinal mucosal laceration in the region of the gastroesophageal junction and gastric cardia typically occurring after repeated episodes of severe vomiting or retching.

- Vomiting, retching, or vigorous coughing will often, but not always, precede hematemesis.

- There are no specific physical exam findings. Patients may be clinically stable or present with tachycardia, hypotension, melena, hematochezia, epigastric pain, back pain, syncope, or hemorrhagic shock.

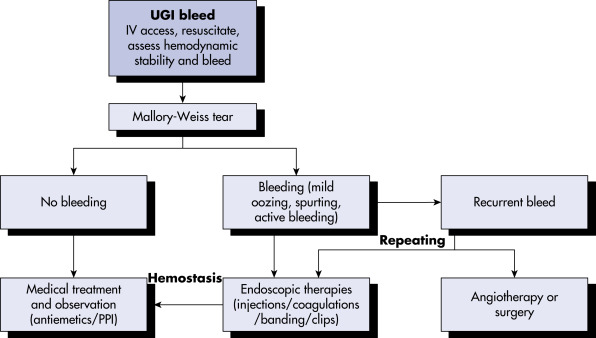

- Bleeding may be self-limited or severe. Rebleeding is more common in patients with advanced alcoholic liver disease.3

- Tears may be seen in association with other upper GI tract lesions, including hiatal hernia (present in as many as 90% of patients), ulcers, and esophageal varices, particularly in alcoholics.

- An acute increase in intragastric and intraabdominal pressure is transmitted to the gastroesophageal junction and esophagus, resulting in mucosal laceration.

- Vomiting may be associated with alcohol use, cannabinoid use, ketoacidosis, ulcer disease, uremia, pancreatitis, chemotherapy, cholecystitis, pregnancy (in particular associated with hyperemesis gravidarum), bulimia, myocardial infarction, or the postoperative period.

- Infrequently reported causes include chest wall trauma (including cardiopulmonary resuscitation), hiccups, coughing, seizures, lifting/straining, blunt abdominal trauma, acute severe asthma, labor and delivery, and even primal scream therapy.

- Tears may be iatrogenic, related to routine endoscopy (especially in struggling, retching, or older patients, or in association with hiatal hernias or distal gastrectomy), enteroscopy with or without spiral or balloon overtubes, esophageal dilation, lower esophageal pneumatic disruption therapy for achalasia, endoscopic submucosal dissection, transesophageal echocardiography, bariatric intragastric balloons, or in association with polyethylene glycol electrolyte colonic lavage preparation.4

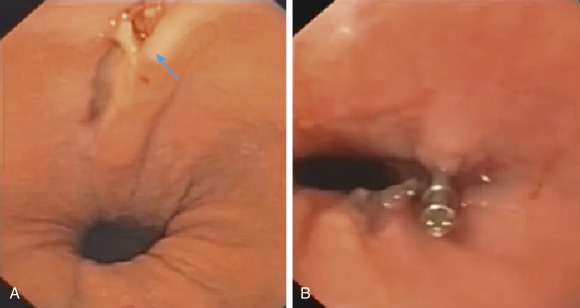

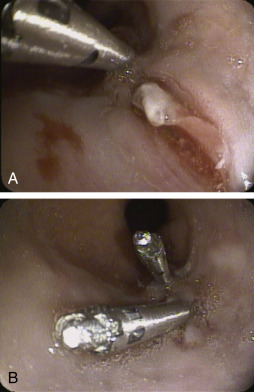

- Tears are frequently found on the right lateral wall of the esophagus.