AUTHORS: Rachita Pandya, BA and Lisa Pappas-Taffer, MD

DefinitionDermatitis herpetiformis (DH) is an autoimmune blistering disease that is a cutaneous manifestation of celiac disease (CD). It is associated with gluten-sensitive enteropathy in nearly all cases, although only 20% of patients have gastrointestinal symptoms.1 15% to 25% of patients with CD will have DH.2

SynonymsDH

Duhring disease

| ICD-10CM CODE | | L13.0 | Dermatitis herpetiformis |

|

Epidemiology & DemographicsPrevalence (In U.S.)11 cases per 100,000 persons per yr3; prevalence for CD is one in 133 adults

Predominant SexMale predominance (2:1)3; however, female predominance in children4

Predominant AgeFourth decade of life, but can occur at any age3

Predominant RaceMost common in Caucasians of northern European ancestry3

GeneticsBoth CD and DH have a strong genetic component. 10% to 15% of patients with DH have a first-degree relative with either DH or CD.5 Specific HLA genes (involved in processing gliadin antigen in genetically susceptible individuals) have also been shown to predispose to developing DH (HLA-DQ2 in 90%, DQ8 in the remaining 10%6). However, less than 50% of genetic predisposition is attributed to HLA genes. Autoimmune disorders associated with dermatitis herpetiformis are summarized in Table E1.

TABLE E1 Autoimmune Disorders Associated With Dermatitis Herpetiformis

| Common |

- Autoimmune thyroid disease (Hashimoto thyroiditis)

- Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus

|

| Uncommon |

|

| Rare |

- Addison disease

- Autoimmune chronic active hepatitis

- Alopecia areata

- Myasthenia gravis

- Sarcoidosis

| - Systemic sclerosis (scleroderma)

- Sjögren syndrome

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Vitiligo

|

From Bolognia J: Dermatology, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2018, Elsevier.

Physical Findings & Clinical Presentation

- Classically, the lesions of DH are small, grouped, “herpetiform” vesicles that are distributed symmetrically on extensor surfaces (elbows [Fig. E1], knees [Fig. E2], scalp, back, and buttocks [Fig. E3]). However, due to intense pruritus and scratching, pinpoint erosions and excoriations in the above distribution are often the most prominent findings on examination, with intact vesicles rarely seen.

- Spontaneous improvement with cyclic exacerbations is common.

- Celiac-type enamel defects to permanent teeth, oral vesicles, or palmoplantar purpura have been reported as potential associated findings.3

Figure E1 Dermatitis herpetiformis.

From Micheletti RG et al: Andrews’ diseases of the skin, clinical atlas, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2023, Elsevier.

Figure E2 Dermatitis herpetiformis.

From James WD et al: Andrews’ diseases of the skin, ed 12, Philadelphia, 2016, Elsevier.

Figure E3 Dermatitis herpetiformis.

From Micheletti RG et al: Andrews’ diseases of the skin, clinical atlas, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2023, Elsevier.

PathogenesisCD and DH are both autoimmune, mediated by immunoglobulin A (IgA) class autoantibodies. Dietary gluten is central to the pathogenesis in both. In genetically predisposed individuals, it is hypothesized that the gluten by-product, gliadin, complexes with tissue transglutaminase (tTG) in the gut, binding as an antigen to HLA-DQ2 on T cells, creating an immune response that results in anti-tTG IgA antibodies (i.e., antiendomysial antibodies) in the blood.7 tTG cross-reacts with epidermal TG (eTG). The blood of CD patients with and without skin disease is found to have both skin and gut anti-TG IgA antibodies.8 Yet, it is thought that the high-affinity IgA against eTG form complexes that are responsible for DH.8 The deposition of IgA-eTG complexes in the papillary dermis triggers an immunologic cascade resulting in neutrophil recruitment and complement activation.8

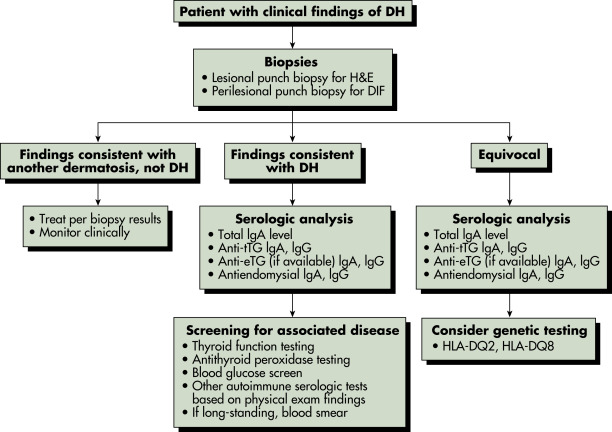

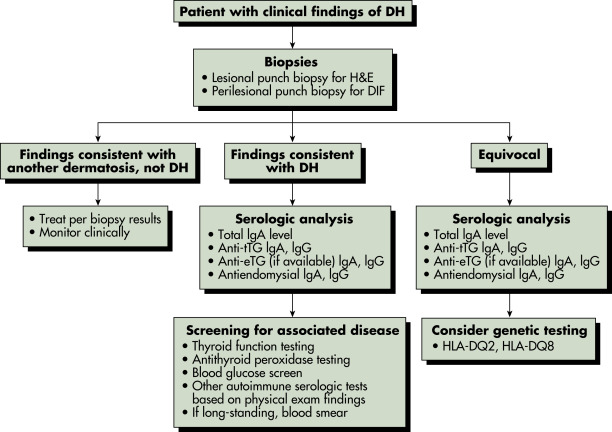

Physical examination and routine histopathology are often suggestive of DH; however, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) of a perilesional skin biopsy has pathognomonic findings9 and is the gold standard for diagnosis. Fig. E4 describes an approach to the patient with suspected dermatitis herpetiformis.

Figure E4 Approach to the Patient with Suspected Dermatitis HerpetiformisDh, Dermatitis Herpetiformis; Dif, Direct Immunofluorescence; Etg, Epidermal Transglutaminase; H&E, Hematoxylin and Eosin; HLA-Dq2, Histocompatibility Locus Antigen Haplotype Dq2; HLA-Dq8, Histocompatibility Locus Antigen Haplotype Dq8; Ig, Immunoglobulin; Tig, Tetanus Immune Globulin. (From Bolotin D, Petronic-Rosic V: Dermatitis Herpetiformis: Part II. Diagnosis, Management, and Prognosis, J Am Acad Dermatol 64:1027-1033, 2011.)

Differential Diagnosis

- Clinically and histologically, the differential diagnosis includes10:

- Linear IgA dermatosis

- Bullous pemphigoid

- Bullous lupus

These diagnoses can be differentiated by DIF on perilesional skin biopsy.

- Other clinical diagnoses to consider8-10:

- Scabies (check for interdigital burrows and involvement of genitalia)

- Arthropod bite (urticarial papules, often in groups of three, over-exposed areas)

- Eczematous dermatitis (ill-defined, erythematous and xerotic plaques or deep seeded vesicles on hands)

- Herpes simplex or zoster infection (painful, not symmetric)

- Generalized pruritus (no blister history, not limited to extensor surfaces)

Workup and Laboratory Tests

- Evaluation for gastrointestinal symptoms, family history of DH or CD, and pruritus should be sought in patients with suspected DH.

- Lesional skin biopsy: Will demonstrate a neutrophil-rich subepidermal bulla10 and rule out many conditions.

- DIF of normal-appearing perilesional skin biopsy: Will demonstrate pathognomonic IgA deposits localized to the dermal papillae and dermal-epidermal junction in a granular pattern.10

- Serology (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA]) for IgA tTG, ELISA for IgA eTG, if available, and indirect immunofluorescence for IgA endomysial antibodies (total IgA) can be used to aid in the diagnosis of DH in cases where the DIF is negative or equivocal, or for monitoring disease activity response to treatment.9 Although these circulating antibodies in the blood exist, there is a high false-negative rate for anti-tTG and for antiendomysial antibodies (one third of DH patients are negative for antiendomysial antibodies11), and their absence does not exclude the diagnosis. Also, IgA-deficient DH patients may also have negative serologic results.9 Those with the presence of circulating antibodies will have a reduction in levels in response to treatment adherence.9

A gluten-free diet (GFD) and dapsone are considered first-line therapy and are often started in conjunction.9

- GFD improves symptoms of both GI and skin disease, with GI responding quicker (skin responds after 2 mo).9 A retrospective study showed remission (2 yr without symptoms) in 12%.12

- Dapsone results in improvement of skin manifestations within days but does not treat GI manifestations.9,13 Dapsone is typically tapered over time, while lifelong gluten avoidance is often necessary.9

- One study demonstrated GFD alone was comparable to GFD plus dapsone in the treatment of DH; hence GFD is an essential component in the treatment of DH.

Nonpharmacologic Therapy

- First line: GFD:

- Avoid barley, rye, wheat (can consume rice, corn, and oats).

- Consultation with a dietitian is recommended.

- Most patients need to follow diet indefinitely; however, cases of spontaneous remission have been reported.14

- Second line: Elemental diet (controversial):

- Can consider elemental diet (avoidance of whole proteins) in those patients who do not adequately respond to a strict GFD8; however, data are limited.

Acute General Rx

- First line: Dapsone:

- Initial dose 25 to 50 mg PO daily with gradual increase to an average maintenance dose of 0.5 to 1 mg/kg daily (often maintenance dose of 100 mg daily).9,13

- Clinical monitoring weekly is recommended to optimize dose (optimal dose is when one to two new lesions/wk).9,13

- Caution: Dapsone may produce hemolysis (especially if G6PD deficiency), agranulocytosis, methemoglobinemia, systemic drug hypersensitivity reaction (DRESS), and long-term, a peripheral neuropathy.

- Baseline labs: CBC, liver function tests (LFTs), G6PD levels. After the initiation of therapy, monitor CBC every wk ×1 mo, then every other wk ×2 mo, monthly ×3 mo, then every 3 to 4 mo. Monitor LFTs every 3 to 4 mo.

- Second-line alternatives:

- Sulfapyridine (500 to 1500 mg/day, compounded medication) or sulfasalazine (500 to 1000 mg bid) may be substituted in cases of dapsone intolerance or in the rare case that neuropathy develops.9 Sulfapyridine must be compounded.

- Case reports of efficacy using topical dapsone 5% twice daily in patients who do not tolerate oral dapsone; also reported to be efficacious as an adjuvant to oral dapsone.15

- Uncontrolled studies and case reports have suggested efficacy with tetracyclines, nicotinamide, cyclosporine, colchicine, and heparin.9,16

- Case reports have documented the use of Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors in clearing DH lesions in those unable to tolerate oral dapsone.17

- Symptomatic relief for pruritus:

- Potent and superpotent topical corticosteroids (atrophy with prolonged use, limit to 14 days per mo), nonsedating antihistamines twice daily, sedating antihistamines at bedtime, mentholated lotion.9

Chronic Rx

- As DH is considered to represent the cutaneous manifestations of CD, lifelong avoidance of gluten is typically recommended. Information about educational resources, such as national and local support groups, should be provided (http://www.celiac.org/).

- Patients with DH and CD have an increased risk of developing Hashimoto thyroiditis (50% with thyroid disease), non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and GI lymphomas.3 An increased incidence of other autoimmune disorders (type 1 diabetes mellitus, pernicious anemia, Addison disease, vitiligo, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and Sjögren syndrome) and osteoporosis have also been reported.3,8,18.

- Screening for thyroid disease (thyroid stimulating hormone [TSH], antithyroid peroxidase antibody titers) is typically recommended.3

- Screening for autoimmune connective tissue diseases should be considered if there are suspicious signs or symptoms.3

- Routine screening for GI lymphomas is controversial.19

Referral

- Dermatologist for skin biopsy and management of cutaneous disease

- Gastroenterologist for evaluation of CD

- Nutritionist to educate patients about gluten-free diet

- National support groups (http://www.celiac.org/) and local support groups