AUTHOR: Patricia Cristofaro, MD

Q fever is a zoonotic systemic febrile illness caused by Coxiella burnetii that may be acute or chronic. The concept of persistent localized disease may soon replace that of chronic Q fever.

- C. burnetii is found worldwide.

- Common animal reservoirs are cattle, sheep, and goats.

- Pets such as cats, rabbits, and pigeons are also reservoirs.

- A parturient cat caused an outbreak in Nova Scotia just by delivering in the same room as a card game.

- Most cases are found in individuals who have direct contact with infected animals (e.g., farmers, veterinarians) or who are exposed to contaminated animal urine, feces, milk, or placental tissues.

- Q fever is seen more often in men than in women (ratio of 3:1).

- Its incidence in the U.S. is increasing, with more than 30 cases recently reported in U.S. due to military personnel recently deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan.

- Travel to Middle Eastern and African countries poses the greatest risk.

- C. burnetii is a CDC class B bioterrorism agent.

- Q fever may be acquired from ingestion of unpasteurized milk or dairy products.

- Q fever is caused by the Proteobacteria C. burnetii.

- C. burnetii is a gram-negative coccobacillus transmitted from arthropods to animals to human beings.

- The disease is acquired most often by inhalation of aerosols. In the lungs, it proliferates in macrophages and then gains access to the bloodstream, producing a transient bacteremia. Thereafter it can invade many organs, most commonly the lungs and liver (Fig. E1).

- There is an incubation period of 3 to 30 days before systemic symptoms manifest.

- Persons with abnormal heart valves, prosthetic valves, and endovascular grafts are at high risk of progression to chronic Q fever. This includes individuals with bicuspid aortic valves.

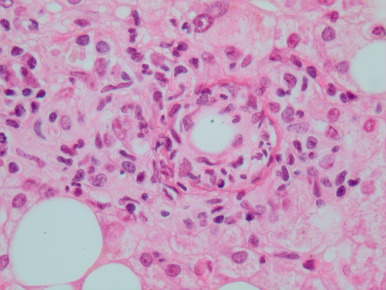

Figure E1 Histology of the liver in a patient with acute Q fever.

Hepatic ring granuloma of Q fever with peripheral epithelioid macrophages and lymphocytes admixed with neutrophils, characteristic central “doughnut” hole, and ring of fibrin. Note the “fatty liver” parenchyma (hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification ×400).

From Ryan ET: Hunter’s tropical medicine and emerging infectious diseases, ed 10, Philadelphia, 2020, Elsevier.