Management (Fig. 4) should be based on primary symptoms and patient goals; this may include observation with close follow-up, medical management, temporizing surgical therapies, embolization (Fig. E5), or definitive surgical procedures. Treatment is indicated if bleeding requires blood transfusions, renal function is affected by size of the enlarged fibroid uterus, or when symptoms are present and are severe enough to be unacceptable to the patient.

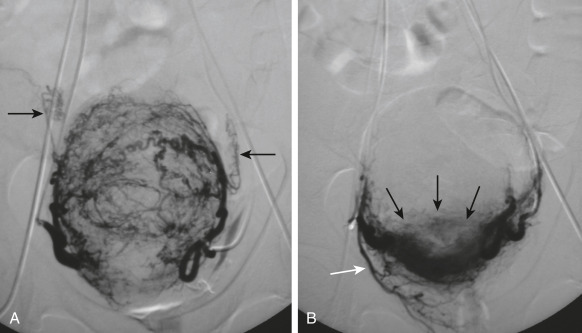

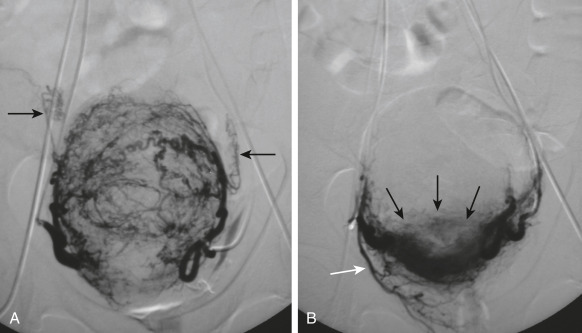

Figure E5 Uterine Fibroid EmbolizationA, Angiographic Image of Uterine Leiomyoma Before Uterine Fibroid Embolization. Arrows Point to Preembolization Uterine Artery. B, Postembolization Image of Same Devascularized Myoma with Normal Myometrial Perfusion Maintained (Black Arrows). White Arrow Points to Patent Cervicovaginal Branch of Uterine Artery at Completion of Embolization.

From Spies JB, Czeyda-Pommersheim F: Uterine fibroid embolization. In Mauro MA et al [eds]: Image-guided interventions, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2014, Elsevier, pp 542-546. In Gershenson DM et al: Comprehensive gynecology, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2022, Elsevier.

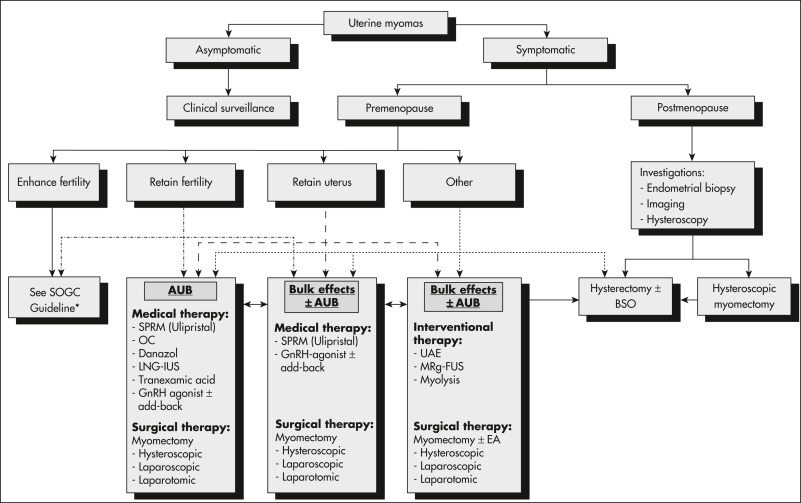

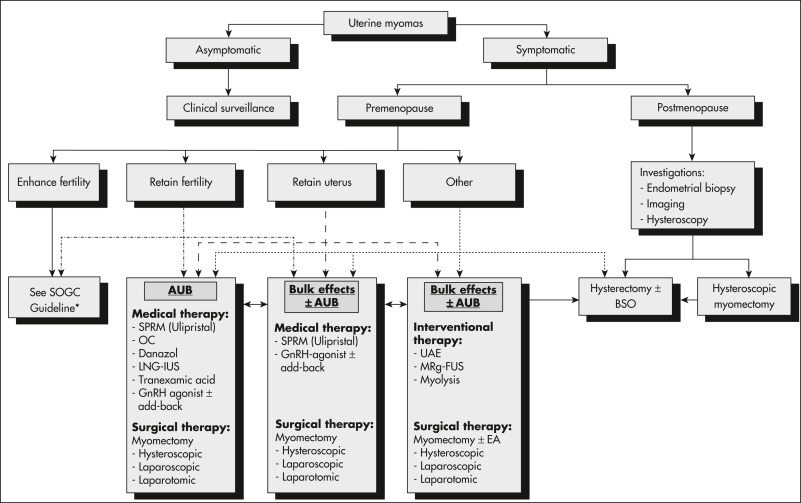

Figure 4 Algorithm for the management of uterine fibroids.

AUB, Abnormal uterine bleeding; BSO, Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; GnRH, Gonadotropin-releasing hormone; LNG-IUS, levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system; MRg-FUS, magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound; OC, oral contraceptives; SPRM, selective progesterone-receptor modulator; UAE, uterine artery embolization.

From Vilos GA et al: The management of uterine leiomyomas, J Obstet Gynaecol Can 37[2]:163, 2015; and Carranza-Mamane B et al; Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility Committee: the management of uterine fibroids in women with otherwise unexplained infertility, SOGC Clinical Practice Guidelines, J Obstet Gynaecol Can 37[3]:277-285, 2015.

Nonsurgical Rx

- Patient observation and follow-up with periodic repeat pelvic exams to ensure that tumors are not growing rapidly, which could suggest malignancy.

- Hormonal therapies reduce bleeding symptoms and many have the added benefit of contraception. There is no evidence that exogenous estrogen or progestin increases risk of myomas.

- Combined hormonal methods with estrogen and progestin, including oral contraceptives, contraceptive patch, contraceptive vaginal ring

- Progestin-only agents including oral progestins, intramuscular progestin injection, levonorgestrel intrauterine device (IUD)

- Progesterone IUD significantly improves menorrhagia, but expulsion rate with myomas is 10% to 15%, and intracavitary fibroids are a contraindication. Enormous uteri may lead to migrated strings precluding simple retrieval

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist, leuprolide, results in 25% to 50% reduction in uterine volume and cessation of menses within 3 mo of initiating treatment. Hypoestrogenism, reversible bone loss, and hot flushes are side effects. Consider low-dose progesterone replacement (add-back therapy) to minimize hypoestrogenic effects. GnRH agonist therapy is not recommended for longer than 6 mo without add-back or 12 mo with add-back due to these effects, so goal is to bridge to other treatment.

- Regrowth and return of bleeding symptoms occurs in 50% of treated patients within 3 mo after cessation.

- Indications for GnRH agonist:

- Anemia treatment to normalize hemoglobin before surgery

- Avoiding surgery in patients approaching menopause

- Preoperatively for large myomas to make hysterectomy, hysteroscopic resection/ablation more feasible

- Medical contraindication for surgery

- Use of GnRH agonists alters the consistency of the fibroid, making myomectomy more challenging.

- GnRH antagonists (FDA approved 2020 and 2021)-elagolix and relugolix. Both treatment options contain hormonal add-back (estradiol and norethindrone acetate) and can be prescribed for max of 2 yr. May still have light menses. Possible adverse effects include high blood pressure, worsening of lipids and liver enzymes, and loss of bone mineral density. Patients with history of venous thromboembolism or those who are over the age of 35 and smoke should not take these medications.

- Nonhormonal medical therapies:

- Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs for pain; data do not support use as monotherapy for AUB-L menorrhagia.3

- Tranexamic acid, an oral antifibrinolytic, can decrease menorrhagia by 40% to 65%. Side effects include abdominal cramps, headaches, fatigue, and increased risk of venous thromboembolism.

- Other drugs used and under investigation:

- Danazol: Androgen and inhibitor of steroidogenesis, side effect of hirsutism.

- Mifepristone: Antiprogesterone reduces fibroid volume 40% to 50% with amenorrhea.

- Raloxifene: Selective estrogen receptor modulator, either alone or with GnRH agonist, reduces fibroid volume 70% up to 1 yr but only in postmenopausal patients.

Surgical Rx

- Indications:

- Abnormal uterine bleeding with anemia refractory to hormonal therapy

- Chronic pain with severe dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, or lower abdominal pressure/pain

- Acute pain, torsion, or prolapsing submucosal fibroid

- Urinary symptoms or signs such as hydronephrosis

- Infertility or recurrent pregnancy loss with endometrial cavity-distorting fibroid as only finding4

- Enlarged uterus with compression symptoms or discomfort

- Rapid uterine enlargement premenopausal or any growth after menopause-this indication should involve gynecologic oncologist

- Procedures:

- Hysterectomy (definitive procedure): Vaginal, laparoscopic, robotic, or abdominal approach, dependent on surgical preference/expertise and uterine size.

- Myomectomy (preserves fertility): May be performed via abdominal, laparoscopic, or robotic approach; 60% recurrence at 5 yr postop5; significant hemorrhage risk, so control anemia preop

- Vaginal myomectomy for prolapsed pedunculated submucosal fibroid

- Hysteroscopic resection: Typically at least 50% of the fibroid must be intracavitary for a hysteroscopic approach to be successful. May need to be done in stages.

- Radiofrequency volumetric thermal ablation: FDA-approved uterine-sparing procedure in which laparoscopic or transcervical ultrasound-guided ablation of fibroids induces myolysis (necrosis) resulting in fibroid shrinking. Preliminary data on subsequent pregnancy are limited, but encouraging.3,6

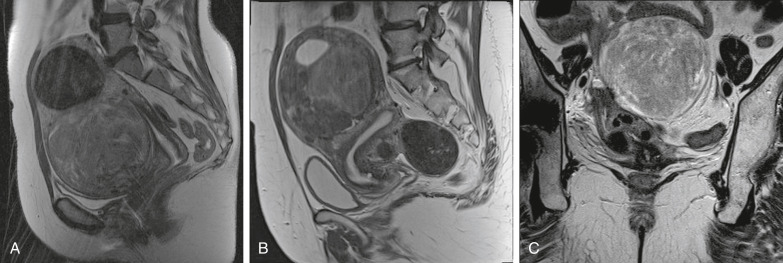

- Magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound: ultrasound energy focused to cause fibroid coagulative necrosis. Enables fertility preservation, but due to numerous contraindications, many patients are ineligible.3

- Uterine artery embolization (UAE): Alternative to surgery performed by interventional radiologist, but its less invasive nature should be balanced against a higher rate for treatment failure or complications at 5 yr. Age 40 or less at time of embolization and history of previous myomectomy are predictors of UAE failure. If the patient wishes to preserve future fertility, UAE should not be performed. Contraindicated if history of GnRH agonist use or salpingectomy.3

- Endometrial ablation: Decreases menorrhagia, has limitations based on uterine cavity distortion.

- Patients who receive procedures other than definitive management are more likely to result in a second surgery if younger age/less proximity to menopause.

Complications

- Degeneration occurs when the fibroid outgrows its blood supply. During pregnancy, rare but typically seen in the second trimester. May see fever and leukocytosis, but symptoms improve within 48 h.3

- Leiomyosarcoma (<0.1%). The U.S. FDA voiced concern regarding the use of power morcellation in the peritoneal cavity during minimally invasive laparoscopy if a tissue containment system is not used due to the possibility of spreading occult malignancy. In 2020, FDA recommended against power morcellation if age >50 yr or postmenopausal.1

DispositionFibroids continue to grow during reproductive years, but symptoms improve after menopause.

Complementary & Alternative TherapyLack of evidence to support acupuncture or herbal therapy.2 There is some research supporting use of vitamin D.7

ReferralConsultation with gynecologist for management and with gynecologic oncologist if suspicious of malignancy

Related ContentUterine Fibroids (Patient Information)

Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding (Related Key Topic)