Author: Ajay S. Koti, MD and Emily C.B. Brown, MD, MS

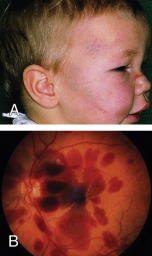

Abusive head trauma (AHT) refers to a distinct form of traumatic brain injury that occurs as a consequence of inflicted, or nonaccidental, injury to a child, typically under the age of 4 yr. Formerly known as "shaken baby syndrome," AHT arises from shaking, blunt impact, or a combination thereof.1 The injury pattern may not clearly differentiate between these mechanisms. AHT is a life-threatening condition, and survivors commonly suffer long-term sequelae. The constellation of findings most often includes subdural hemorrhage, and extensive retinal hemorrhages and/or encephalopathy frequently accompany the intracranial findings. Children with AHT may present with or without evidence of additional cutaneous, musculoskeletal, or visceral injuries (Fig. E1). AHT is often challenging to diagnose because the clinical manifestations may be vague or nonspecific, caregivers may not report a history of trauma, and there may be no external sign of injury.

- Shaken baby syndrome

- Infant whiplash syndrome

- Inflicted pediatric neurotrauma

- Nonaccidental head injury

- AHT

| ||||||||||||||||

AHT is the most common cause of fatal head injuries in children under 2 yr old, accounting for 53% of serious or fatal traumatic injuries. It is the leading cause of abusive fatalities overall.2 Morbidity and mortality are higher for victims of AHT than for children injured accidentally. Approximately one in four cases are fatal.1 Long-term neurologic sequelae are common, occurring in 70% of survivors. These include visual deficits, neurocognitive problems, seizure disorders, cerebral palsy, and intellectual disability.1

Males are found to be at higher risk for AHT than females, by as much as a 2-to-1 margin.

Victims of AHT are typically younger than 1 yr of age, with a median age of 4 mo. The peak incidence of fatal AHT occurs even earlier, at 1 to 2 mo, which overlaps with the peak of infant crying; this has often been reported as a trigger of abuse.2 Infants are particularly susceptible to injuries from shaking and/or impact due to their unique body proportions, neural immaturity, and neuroanatomy.3

Risk factors for AHT include prematurity, perinatal illness, multiple gestations, male sex, and excessive crying. Other psychosocial stressors, such as parental substance use or mental illness, lack of access to child care, and poverty, have been associated with AHT on a population level. Those who inflict AHT are more often males.4,5 It is important to note, however, that AHT is a medical diagnosis that affects infants of every socioeconomic circumstance and caregiving environment, and a diagnosis of abuse should not be influenced by psychosocial risk factors.

Infants with AHT often present with nonspecific symptoms (e.g., drowsiness, lethargy, irritability, vomiting, seizures, irregular respirations, or apnea) and either no history of trauma or an inconsistent report of a low-height fall.3 Symptoms can range in severity, and it is not unusual for infants to present with an unexplained coma or arrest. Examination findings include bruising, intraoral injuries such as a torn frenulum, macrocephaly, and a bulging fontanelle, but many infants have no external signs of trauma. Subdural hemorrhage is the most common radiologic finding in AHT, and indeed, AHT is one of the most common causes of subdural hemorrhage in infants. Other neuroimaging findings include cerebral edema, loss of gray-white differentiation, parenchymal injury, torn/thrombosed bridging veins, cervical spine ligamentous injuries, and spinal subdural hematoma.2 Fractures, such as posterior rib fractures and classic metaphyseal lesions, may be detected on skeletal survey, and dilated retinal examination may reveal retinal hemorrhages. Often these are bilateral, too numerous to count, in multiple layers, and extending to the ora serrata (retinal periphery), though a fraction of patients will have no retinal hemorrhages at all. Some will have retinoschisis. Delayed diagnoses are common, and AHT is missed by medical providers approximately 30% of the time on initial presentation.6 This often leads to recurrent and escalating injuries to the child until the abuse is recognized.7 Physicians often fail to detect AHT among children of intact, white families, likely reflecting bias in the suspicion of abuse.6 It should be noted that the diagnosis of abuse is based on a recognizable constellation of clinical findings and not the family’s psychosocial circumstances.

AHT is thought to occur from rotational acceleration-deceleration forces, such as those generated in shaking; however, blunt impact trauma can cause overlapping findings. These forces are typically not concordant with typical infant caregiving or minor accidental trauma. Subdural hemorrhages arise from bridging vein trauma. Children with more severe presentations may have traumatic axonal injury. Vitreoretinal traction accounts for retinal hemorrhages, which may occur with retinoschisis. Victims of AHT will frequently experience multiple episodes of trauma, highlighting the importance of diagnosis to prevent further harm.