Subject to special exceptions, a pharmacist may dispense schedule II drugs only pursuant to a written prescription, signed by an individual practitioner (21 C.F.R. § 1306.11(a)). Electronic prescriptions for schedule II drugs also are permitted (discussed under "Electronic Transmission Prescriptions"), provided all DEA requirements are met. Schedule II prescriptions may not be refilled (21 C.F.R. § 1306.12(a)). Pharmacists must reconcile federal with state requirements, as many states have additional or stricter requirements regarding schedule II prescriptions. For example, although federal law does not have a limit on the quantity ordered or a time frame for filling schedule II prescriptions, many states have specific rules addressing these matters.

State Accountability for Controlled Substance Prescriptions

In the past, some states required prescribers to issue schedule II prescriptions on multiple copy, state-issued prescription forms. Typically, only the prescriber could request and possess these forms. When the prescriber executed a multiple copy prescription form, generally, the prescriber kept one copy, the dispensing pharmacy kept one copy, and the pharmacy sent another copy to a state office. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Whalen v. Roe, 429 U.S. 589 (1977; discussed in the case studies section) that it does not violate a patient's right of privacy when prescription information is shared with the state.

Electronic data transmission programs (known as prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs)) have replaced state multiple copy prescription programs and have been implemented in all states and the District of Columbia. State PDMPs generally require the electronic reporting of all controlled substance prescription information, not just schedule II prescriptions (discussed under "State Electronic Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs").

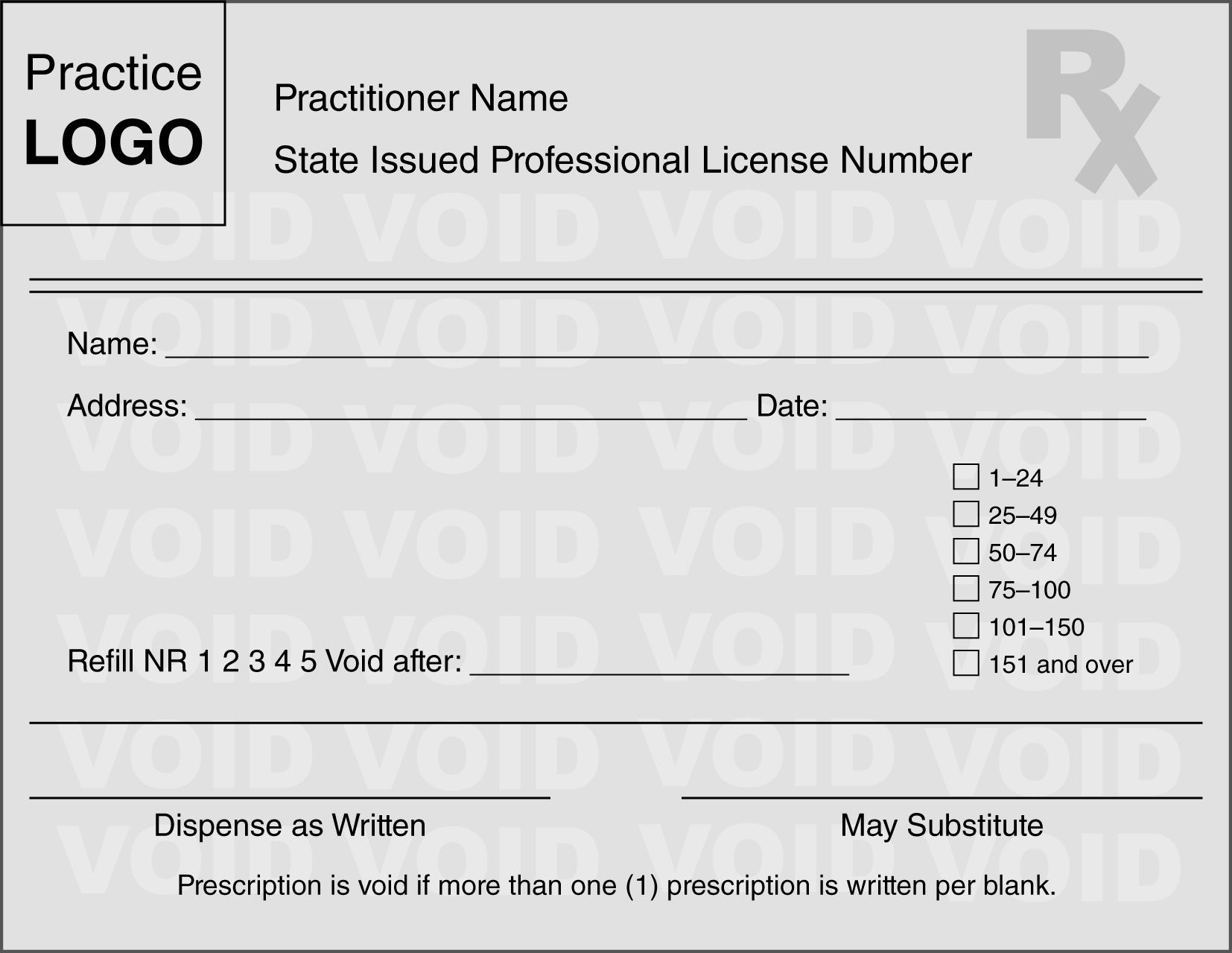

One effort various states make to help address fraudulent written prescriptions includes the requirement for prescribers to use security or tamper-resistant prescription pads. Typically, in order for written prescriptions for controlled substances to be filled at pharmacies in the state, the prescriptions must be written by prescribers on state-approved prescription pads only available from state-approved vendors. Approved prescription pads typically include numerous security features to prevent unauthorized copying or fraud, including watermarks and quantity check-off boxes. A template/example used by numerous states is provided in Figure 5-1. Federal requirements regarding tamper-resistant prescription pads are discussed under "Tamper Resistant Prescription Pads."

Sample security/tamper-resistant prescription pad.

Courtesy of State of Indiana Professional Licensing Agency.

As an additional effort to address fraudulent controlled substance prescriptions, some states are considering or have already mandated that controlled substances be electronically prescribed. The SUPPORT Act of 2018 also requires electronic prescribing of controlled substances covered under Medicare Part D. As of 2022, CMS requires electronic prescribing for CII, CIII, CIV, and CV prescriptions with specific exceptions. Exceptions include when the prescriber and dispensing pharmacy are the same entity, when prescribers issue 100 or fewer controlled substance prescriptions per calendar year, when prescribers are in a natural disaster area, and/or when prescribers have been granted a waiver based on circumstances beyond their control.

Emergency Situations

Emergency situations constitute an exception to the requirement that a pharmacist may dispense schedule II drugs only pursuant to a written (or electronic) prescription. In an emergency situation, a pharmacist may dispense a schedule II drug on the oral authorization of an individual practitioner, provided that:

The quantity prescribed and dispensed is limited only to the amount necessary to treat the patient for the emergency period. (Note: Some state regulations are stricter and provide for a numerical quantity or day supply limit that can be prescribed.)

The prescription must be immediately reduced to writing by the pharmacist and shall contain all required information, except the signature of the prescriber.

If the prescriber is not known to the pharmacist, the pharmacist must make a reasonable, good-faith effort to determine that the oral authorization came from a registered individual practitioner. This reasonable effort could include a callback to the prescriber using the phone number in the telephone directory rather than the number given by the prescriber over the phone.

Within 7 days after authorizing an emergency oral prescription, the prescriber must deliver to the dispensing pharmacist a written prescription for the emergency quantity prescribed. (Note: The requirement was 72 hours before March 28, 1997.) The prescription must have written on its face "Authorization for Emergency Dispensing" and the date of the oral order. The written prescription may be delivered to the pharmacist in person or by mail. If delivered by mail, it must be postmarked within the 7-day period. On receipt, the dispensing pharmacist shall attach this prescription to the oral emergency prescription previously reduced to writing. If the prescriber fails to deliver the written prescription within the 7-day period, the pharmacist must notify the nearest office of the DEA. Failure of the pharmacist to do so will void the authority to dispense without a written prescription (21 C.F.R. § 1306.11(d)).

An emergency situation is defined as a situation in which:

Immediate administration of the controlled substance is necessary for the proper treatment of the patient.

No appropriate alternative treatment is available.

It is not reasonably possible for the prescribing physician to provide a written prescription to the pharmacist before dispensing (21 C.F.R. § 290.10).

Facsimile (Fax) Prescriptions for Schedule II Drugs

DEA regulations permit the limited use of faxed prescriptions as another exception to the requirement that pharmacists may only dispense schedule II drugs pursuant to the actual written prescription from the prescriber. In general, faxed schedule II prescriptions are permitted but only if the pharmacist receives the original written and signed prescription before the actual dispensing and the pharmacy files the original (21 C.F.R. § 1306.11(a)). (In essence, this general provision does not provide an exception for pharmacists because the original prescription is still required.) In three situations, however, the faxed prescription may serve as the original:

If the prescription is faxed by the practitioner or practitioner's agent to a pharmacy and is for a narcotic schedule II substance to be compounded for the direct administration to a patient by parenteral, intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous, or intraspinal infusion (21 C.F.R. § 1306.11(e)).

If the prescription faxed by the practitioner or practitioner's agent is for a schedule II substance for a resident of a long-term care facility (LTCF) (21 C.F.R. § 1306.11(f)).

If the prescription faxed by the practitioner or practitioner's agent is for a schedule II narcotic substance for a patient enrolled in a hospice care program certified by/or paid for by Medicare under Title XVIII, or licensed by the state. The practitioner or agent must note on the prescription that the patient is a hospice patient (21 C.F.R. § 1306.11(g)).

Note that for LTCF residents, the prescription may be for any schedule II drug in contrast to prescriptions for home healthcare and hospice patients. Pharmacists may dispense faxed prescriptions for hospice patients regardless of whether the patient lives at home or in an institution. Allowing faxed schedule II prescriptions for home healthcare, LTCF, and hospice patients has somewhat eased the burden of pharmacists, who often find it impractical to obtain the original written prescription for patients in these situations.

Partial Filling of a Schedule II Prescription

One of the important restrictions on prescribing and dispensing schedule II controlled substances is that no refills are permitted. However, there are situations where partial fills of CII medications are permitted. In 2016, the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA) (Public Law 114-198) was passed, which included comprehensive strategies to address the opioid epidemic. One strategy, Section 702 of CARA, amended the CSA (21 U.S.C. 829(f)) to allow pharmacies to provide partial fills of a CII medication up to 30 days from the date of the prescription. For pharmacists to partially fill a CII prescription under CARA, it must be requested by the patient or the prescriber, and the total quantity dispensed in all partial fills cannot exceed the total quantity prescribed.

On August 21, 2023, the DEA finalized regulations to implement the partial fill provisions under CARA (88 Fed. Reg. 46983). The regulations add requirements for documentation of the partial fill on the prescription record, and pharmacists should carefully review DEA rules for compliance with the various scenarios under CARA (21 C.F.R. § 1306.13(b)). When a partial fill is requested by a prescriber, he or she must specify the quantity to be dispensed in the partial filling on the face of the written prescription, in the record of the electronic prescription, or in the written record of the emergency oral prescription. The prescriber may also request a partial fill after an oral consultation with a pharmacist, after the prescription was issued. In these instances the pharmacist must properly document the subsequent partial fill request and all the required information on the prescription. When a partial fill is requested by the patient, the pharmacist must indicate on the prescription that the patient requested the partial fill, the date the request was made, and the quantity dispensed. The DEA has clarified that the patient request does not have to be made in person. For example, a patient could make the request verbally over the phone to the pharmacist, or send a signed note to the pharmacy with a family member. DEA has also stated it will authorize as a valid patient request one from the parent or legal guardian for minor children or the caregiver named in the medical power of attorney for an adult patient.

If state law prohibits or places stricter limits on partial fills, the pharmacist must follow state law. Partial fills of schedule II controlled substances may also be provided under CARA when a pharmacist receives a verbal prescription in an emergency situation. The remainder of the prescription must be provided to the patient within 72 hours. After 72 hours, no further dispensing of the emergency prescription is allowed.

The partial filling of CII medications under CARA has caused confusion in pharmacy practice. This is because there has been a long-standing DEA rule allowing for a partial fill of a schedule II controlled substance within 72 hours when the pharmacy was "unable to supply" the full quantity of the medication (21 C.F.R. § 1306.13(a)). Since CARA was passed in 2016 and the DEA only proposed and finalized its regulations to reflect the partial filling of CII medications under CARA in 2020 and 2023, pharmacists and prescribers have been reluctant to comply with the amended CSA. This prompted Congress, in December 2017, to send a letter to the DEA urging the agency to update the regulations and guidance related to partial filling of CII medications (https://www.grassley.senate.gov/news/news-releases/grassley-colleagues-urge-dea-swiftly-issue-regulations-and-guidance-partial-fill). From a practical standpoint, it is important to keep in mind that CARA was passed in response to the opioid epidemic. Since diversion often occurs from medications stored at home, partial fills could reduce the amount of schedule II controlled substances dispensed as well as the amount remaining unused in homes, possibly preventing abuse and diversion. Thus, the pharmacist should be willing to participate when the circumstances are appropriate and the DEA requirements can be met.

In the 2022 DEA Pharmacist's Manual, the DEA stated "DEA views CARA's partial fill exception to be in addition to the exceptions currently listed under 21 CFR 1306.13." Therefore, the long- standing DEA rule (21 CFR 1306.13(a)) allowing for the partial filling of a schedule II controlled substance when a pharmacist is unable to supply the full quantity called for in a written or emergency oral prescription is still permitted. Under this circumstance, the pharmacist is required to note the quantity supplied on the face of the prescription, in the electronic prescription record, or in the written record of the oral emergency prescription. Furthermore, the pharmacist may fill the remaining portion of the prescription within 72 hours of the first partial filling. If the pharmacist is unable to supply the remaining quantity within 72 hours, the pharmacist has to notify the prescriber and no further quantity is to be supplied beyond 72 hours without a new prescription. In practice, there has been confusion over whether the patient had to obtain the remaining balance within 72 hours. The DEA clarified this concern in the 2022 Pharmacist's Manual, stating "[i]t is the position of DEA that the pharmacy must have the balance of the prescription ready for dispensing prior to the 72-hour limit, but the patient is not required to pick up the balance of the prescription within that 72-hour limit."

Historically, "unable to supply" under the DEA rule meant the pharmacy did not have enough of the medication in stock to supply at the time of dispensing. Subsequently, however, the DEA decided that other situations would also be appropriate, including when the drug was in stock but the pharmacy was waiting for verification of the legitimacy of the prescription; when the patient could not afford to pay for the entire amount; or when the patient did not want the entire amount for some other reason.

Another situation where a pharmacist may partially fill schedule II controlled substances is for patients in LTCFs or for patients with a medical diagnosis documenting a terminal illness. For these patients, schedule II prescriptions may be partially filled to allow for the dispensing of individual dosage units but for no longer than 60 days from the date of issuance (21 C.F.R. § 1306.13(c)). The total quantity of drug dispensed in all partial fillings must not exceed the quantity prescribed. If there is any question regarding whether a patient may be classified as having a terminal illness, the pharmacist must contact the prescriber before partially filling the prescription. Both the pharmacist and the prescriber have a corresponding responsibility to ensure that the controlled substance is for a terminally ill patient. The pharmacist must record on the prescription whether the patient is "terminally ill" or an "LTCF patient." A prescription that is partially filled and does not contain the notation "terminally ill" or "LTCF patient" is deemed to have been filled in violation of the CSA.

For each partial filling, the pharmacist must record:

The date

The quantity dispensed

The remaining quantity authorized to be dispensed

The identification of the dispensing pharmacist

This record may be kept on the back of the prescription or on any other appropriate record, including a computerized system. If a computerized system is used, it must have the capability to permit the following:

Output of the original prescription number; date of issue; identification of the prescribing individual practitioner, the patient, the LTCF (if applicable), and the medication authorized, including the dosage form strength and quantity and a listing of partial fillings that have been dispensed under each prescription

Immediate (real-time) updating of the prescription record each time that the prescription is partially filled (21 C.F.R. § 1306.13(d))

Multiple Schedule II Prescriptions for the Same Drug and Patient Written on the Same Day

The fact that the law prohibits the pre- or postdating of controlled substance prescriptions and the refilling of schedule II prescriptions can create hardships for patients who regularly require the dispensing of drugs in this schedule. Recognizing this, the DEA for years permitted physicians to prepare multiple prescriptions on the same day for the same schedule II drug with written instructions that they be filled on different days. In 2003, the DEA issued a private letter to a physician confirming that this practice is permissible (letter from Patricia Good, DEA, to Howard Heit, physician, January 31, 2003). Subsequently, the DEA posted confirmation of the policy on its website as well as on a pain management website. Then, without warning, the DEA reversed its position and issued a Federal Register notice to this effect in 2004 (69 Fed. Reg. 67170), causing an uproar among pain management and healthcare professional organizations. Nonetheless, the DEA reiterated its new position in another Federal Register notice in August of 2005, (70 Fed. Reg. 50408) stating that this practice amounts to illegal refills.

After repeated complaints from pain specialists, in September of 2006, the DEA issued yet another reversal of opinion, proposing a new regulation on the subject as well as an accompanying policy statement, "Dispensing Controlled Substances for the Treatment of Pain" (71 Fed. Reg. 52724; 71 Fed. Reg. 52715). The policy statement was an attempt by the agency to clarify the legal requirements and agency policy regarding the prescribing of controlled substances for the treatment of pain. The DEA issued the final rule in November of 2007, permitting the issuance of multiple prescriptions subject to the following restrictions (72 Fed. Reg. 64921):

Each prescription must be issued on a separate prescription blank.

The total quantity prescribed cannot exceed a 90-day supply.

The practitioner must determine there is a legitimate medical purpose for each prescription and be acting in the usual course of professional practice.

The practitioner must write instructions on each prescription (other than the first) as to the earliest date on which the prescription may be dispensed.

The practitioner concludes that the multiple prescriptions do not create an undue risk of diversion or abuse.

The issuance of multiple prescriptions must be permissible under state law.

The practitioner must comply fully with all other CSA and state law requirements.