Information ⬇

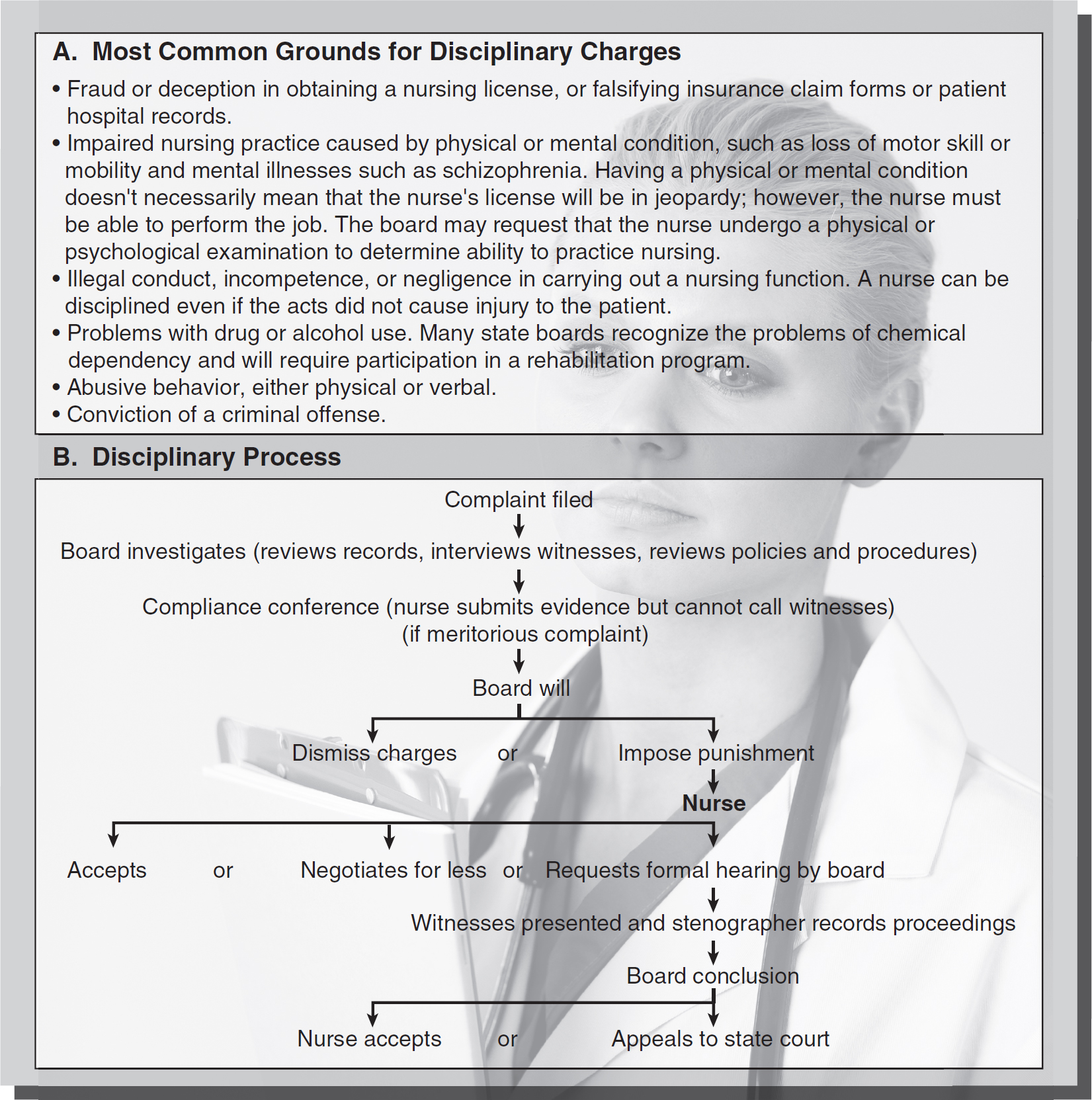

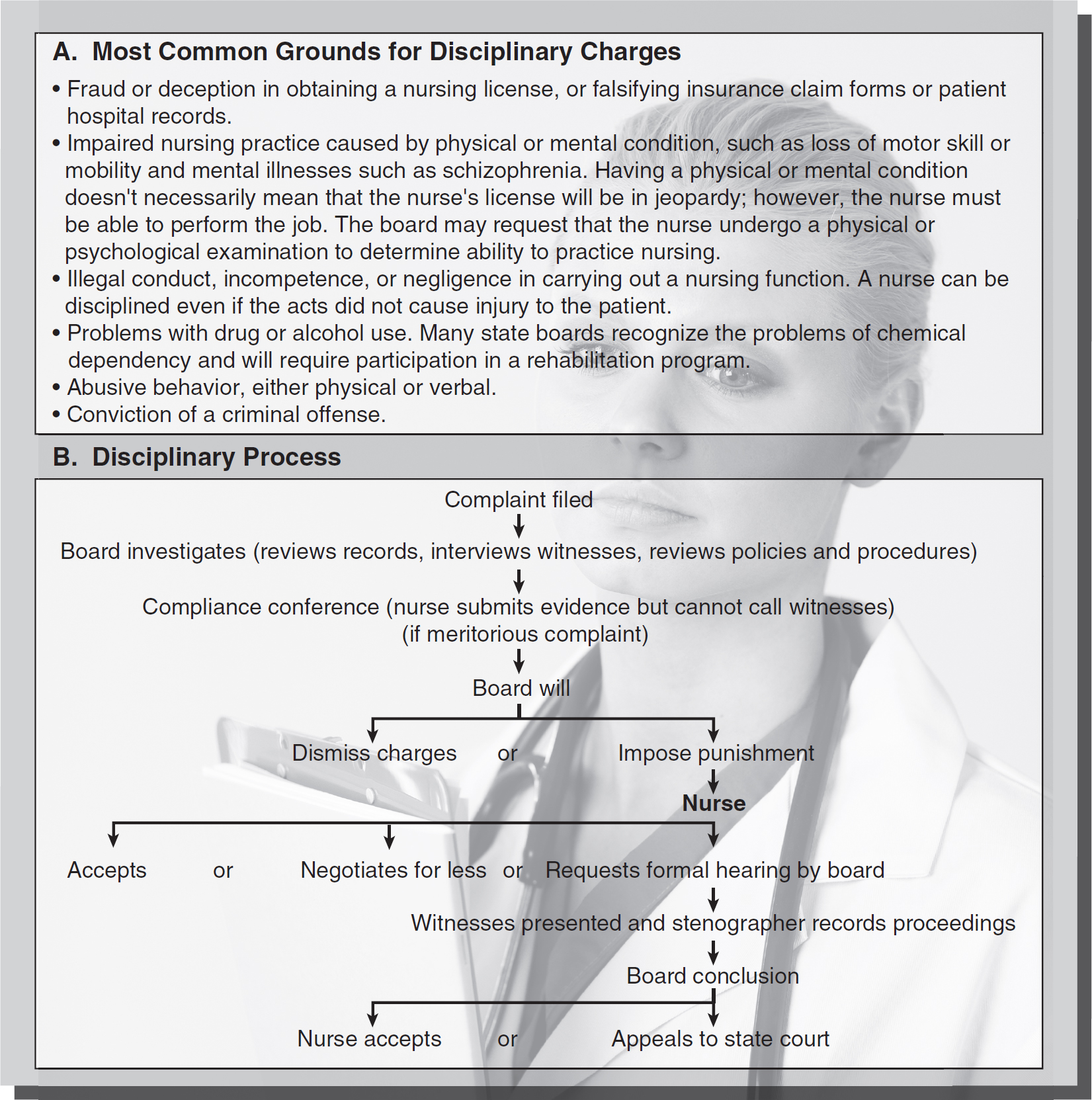

Figure 3-1 Disciplinary charges and process.

© Jones & Bartlett Learning; © Hemera/Thinkstock

Nurses may become involved in different types of actions within the legal system, including criminal actions, administrative law actions, and civil actions. A nurse who makes an error administering a medication is susceptible to a civil malpractice action by the patient who is injured and a disciplinary proceeding by the licensing board. The same nurse may also be subject to criminal charges if the error was so egregious that it constituted negligent homicide or manslaughter.

Criminal Actions ⬆ ⬇

Criminal actions are brought by the state against a defendant accused of breaking a law. Nurses have been prosecuted for crimes such as negligent homicide, manslaughter, theft of narcotics, insurance fraud, and falsifying medical records. A nurse who attempts to conceal a negligent nursing action (civil action) by entering false information in a medical record commits fraud and falsification of a record and could face criminal charges for these crimes.

When a nurse's professional negligence rises to the level of “reckless disregard for human life” (a legal standard of conduct), the nurse may face criminal charges of negligent homicide or manslaughter. Each charge is defined in the state criminal statutes and requires certain elements the state must prove. Two well-known cases involving the initiation of criminal charges against nurses for clinical actions were the Colorado nurse who administered a lethal dose of penicillin and the Wisconsin nurse who administered an epidural anesthetic agent to an obstetric patient instead of an intravenous antibiotic. In both cases, these medication errors resulted in the patient's death. In such cases, a nurse might plead guilty, be acquitted, or take a pretrial intervention (in which no criminal charges are brought as long as the defendants meet certain criteria). The recent case of RaDonda Wright who wrongly administered a paralyzing agent to a patient in 2017 instead of a sedative also resulted in criminal charges and conviction after the patient's death. Nurse Wright was found guilty of criminally negligent homicide and sentenced to 3 years of supervised probation (American Nurse, 2022).

Administrative Law Actions ⬆ ⬇

Administrative law agencies are created by state statutes that define the agencies' purpose, functions, and powers. The state board of nursing is an administrative law agency. The governor of the state typically appoints members to the board of nursing, and most state statutes determine the number of board members, the professional requirements, and the length of appointment. The board of nursing is empowered by the nurse practice act (NPA) to administer and establish the rules and regulations of nursing practice, educational requirements, licensing for practice, licensure renewal requirements, and approval of schools of nursing. In addition, the board enforces the state's NPA and is responsible for disciplinary actions.

Disciplinary Actions ⬆ ⬇

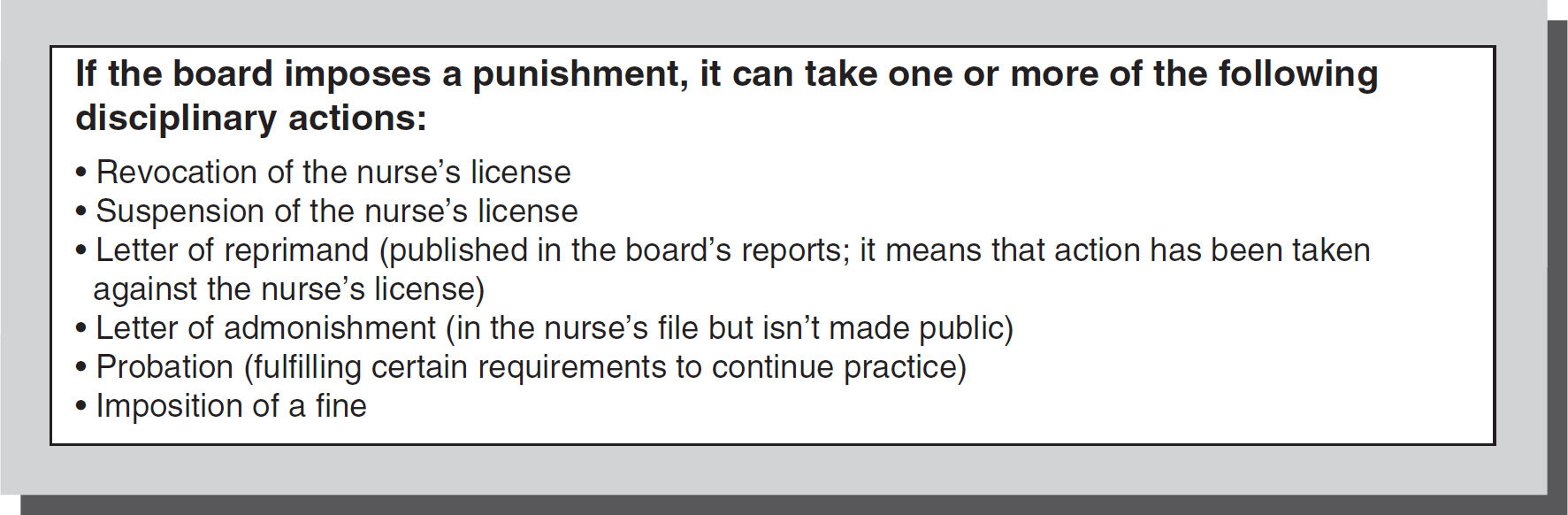

Each board of nursing is charged with the responsibility to maintain the standards of the nursing profession within the state and to protect the public. The board may conduct an investigation to determine whether a nurse has violated the NPA. This is a disciplinary procedure and differs from a civil action or criminal action. Figure 3-1 lists the most common grounds for disciplinary charges. A licensing action begins as a complaint and allegations by a patient, patient's family, employer, or colleagues regarding a nurse's actions. Hospitals are required to report when disciplinary action was taken if a nurse's act puts a patient at a safety risk or is grounds for license suspension or revocation. Discipline can be applied to a nurse's license, and license restrictions are available to the public, usually by accessing the board of nursing's website and searching under the licensee's name. The public can query about any licensed nurse in the state to find out whether the nurse's license is in good standing. The National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) Nursys database can also be queried for information about a licensee's status. Figure 3-2 lists common forms of disciplinary action that the board of nursing can impose.

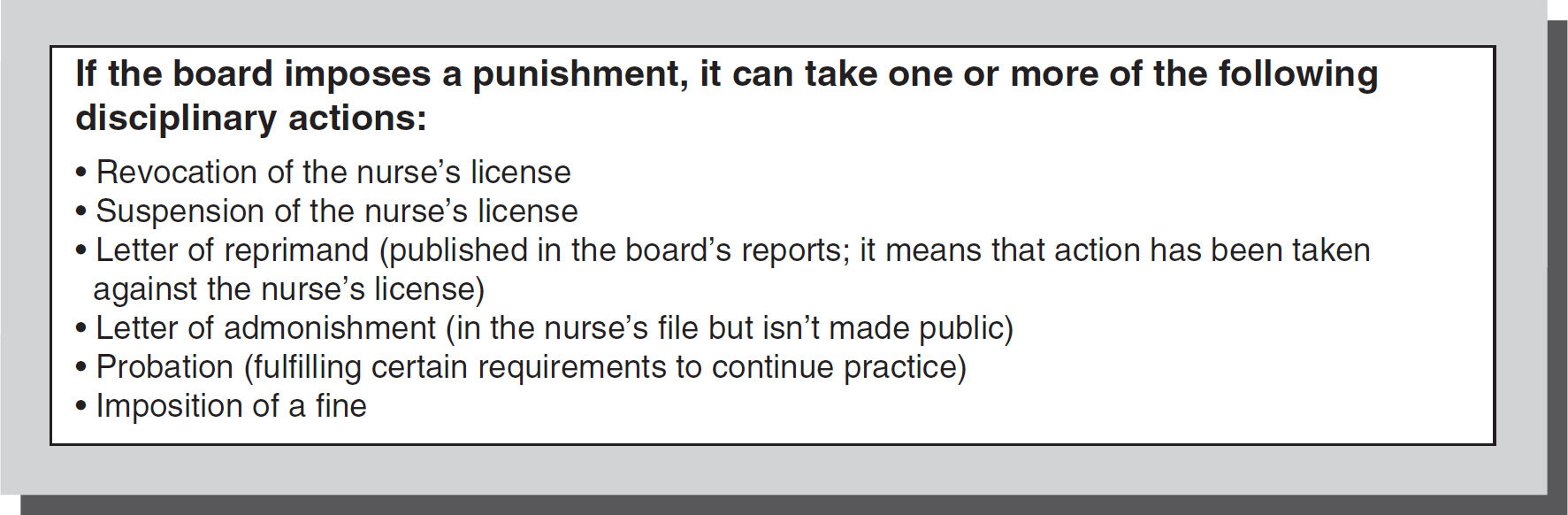

Figure 3-2 Board actions.

© Jones & Bartlett Learning

Administrative disciplinary actions can be against the nursing license or another denial of administrative privilege. Back-timing a morphine order is an example of fraud and resulted in disciplinary action against a nurse's license by the board of nursing in Nevada State Board of Nursing v. Merkley (1997). A willful disregard by a nurse for required reporting regulations resulted in denial of billing Medicare/Medicaid for her employer. This was a serious denial to the administrator of the long-term care facility's ability to be paid for services. The nurse's appeal for judicial review resulted in confirmation of the board's finding that she willfully disregarded the state's mandatory reporting of an accident that results in patient harm (Westin v. Shalala, 1999). Disciplinary actions are also brought for lack of action when there is a duty to act. A nursing supervisor was disciplined for failing to prevent the witnessed abusive acts of a supervised employee. The board's discipline was based on the supervisor's own act (or inaction) and not on the act of the supervised staff (Stephens v. Pennsylvania Board of Nursing, 1995). See Figure 3-2 for the types of disciplinary actions the board may take against licensed nurses.

Investigation and Disciplinary Process ⬆ ⬇

Anyone (e.g., a patient, patient's family member, coworker, or employer) can file a complaint with the board of nursing. The board will notify the nurse in writing that a complaint has been filed and an investigation has been started, and the board may request a written response from the nurse. The response should be provided in an objective manner. Before submitting a response, the nurse should consult an attorney. Most nursing malpractice policies cover attorney fees in disciplinary matters, and this is an important reason that nurses should carry individual malpractice insurance. Retaining an attorney who is familiar with nursing licensure issues is recommended.

A schematic outlining the investigation and disciplinary process is provided in Figure 3-1B.

Administrative Due Process/Appeal ⬆ ⬇

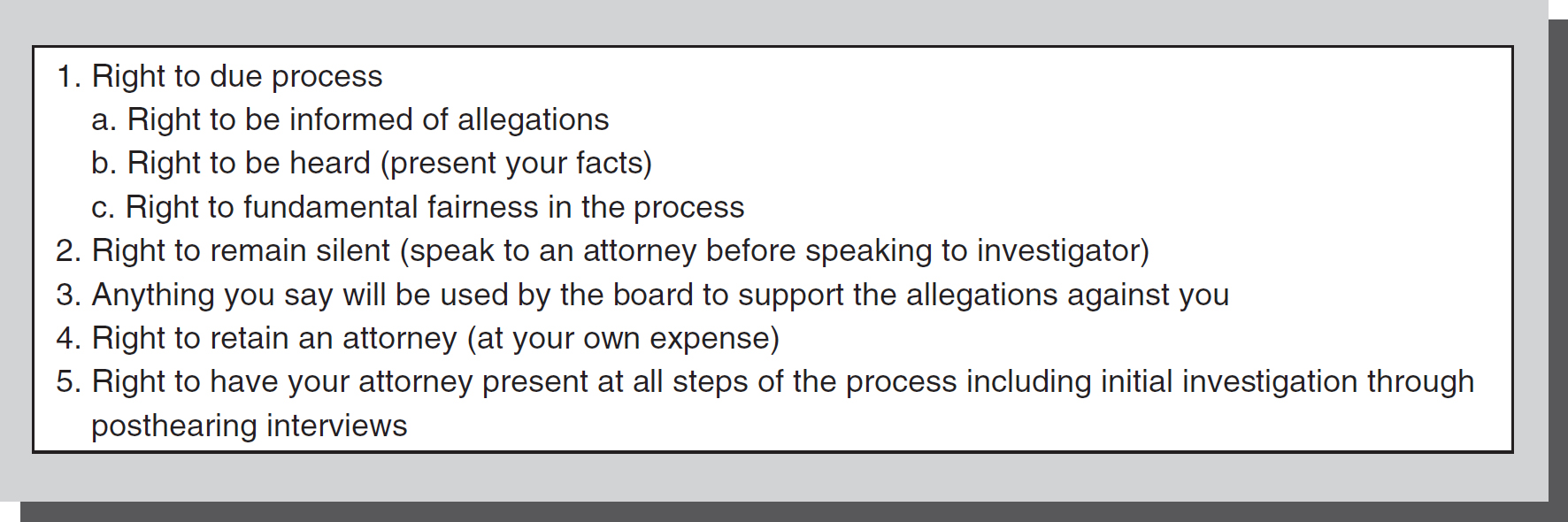

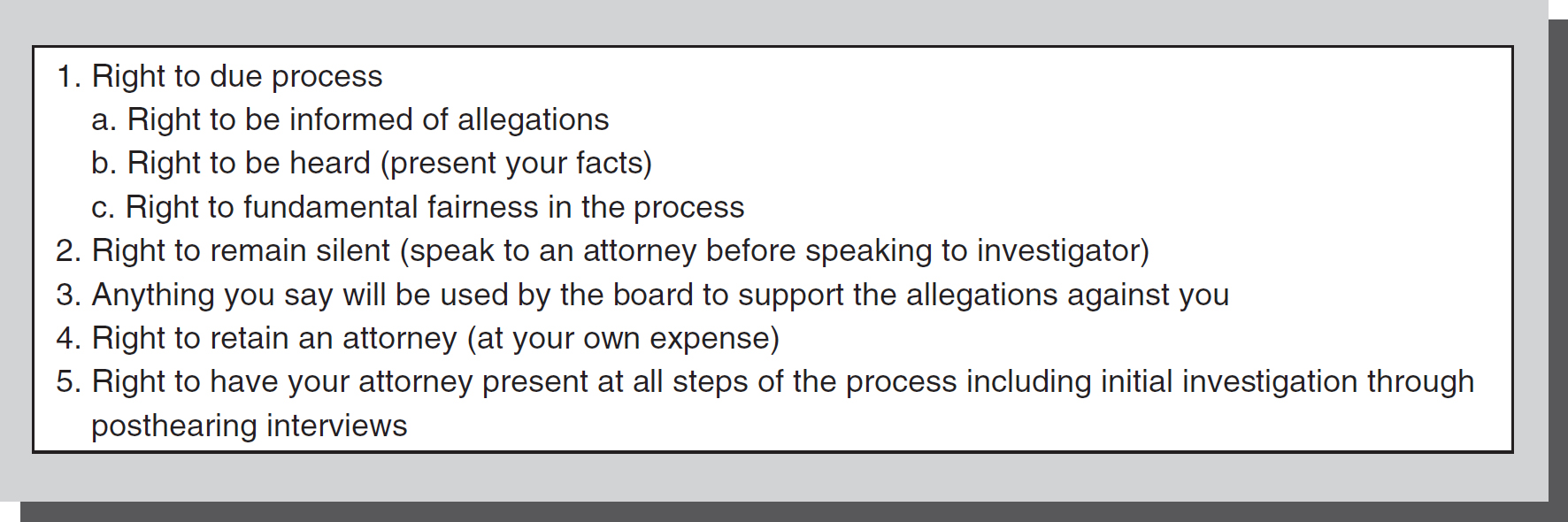

The nurse has a constitutional right called “due process” during the administrative process. Due process ensures that nurses receive a hearing where they have the right to be heard and defend any charges brought against them before the board can terminate a “liberty” (e.g., the practice of nursing). Administrative due process guarantees nurses certain rights through the process (see Figure 3-3).

Figure 3-3 Rights of administrative due process.

© Jones & Bartlett Learning

In certain situations, however, the board has the right to summarily revoke or suspend a nurse's license when the nurse presents an immediate danger to public safety. The practice of nursing, while a property interest under the Constitution, is a privilege granted by the state licensing board upon completion and maintenance of criteria by the nurse. As such, this privilege can be limited by the board's duty to public safety.

Nurses can generally appeal the findings of the state board of nursing through the state court appellate process. The standard of review for the appeals court requires that it find that the board of nursing (BON) acted outside its scope of authority, the action was unconstitutional, the finding was not supported by substantial evidence on the record, or the decision was arbitrary or capricious. Most often, boards' decisions are upheld, because a high standard of proof is required to overturn BON action. In MacLean v. Board of Registration in Nursing (2011), Nurse MacLean appealed the board's decision to suspend her RN license and her right to renew her LPN license for 6 months. The basis for the BON decision was evidence that she had administered a medication to a patient without valid authorization and falsified a telephone order for medication. After a hearing, the board found Nurse MacLean's conduct was in violation of proper nursing conduct and that she had engaged in deceit and unsuitable behavior. The Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts found that the BON decision was supported by substantial evidence, was not arbitrary or capricious, and was not based on any error of law, so it upheld its decision for the license suspension.

Reporting Disciplinary Actions ⬆ ⬇

NCSBN Nursys

Disciplinary action by state boards of nursing as the regulatory agency include reports to national data banks, the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) Nursys database, and exclusion lists that bar participation in state Medicaid- and federal Medicare-funded agencies. Nursys is a website provided by the NCSBN that contains a database of disciplinary action information from all participating member states and territories. When one state takes action against a nurse, the information is entered into Nursys so that other jurisdictions and even the public can access the information. If a nurse applies for licensure in another jurisdiction or for employment, this database is consulted. If an issue related to a license in another state has not been resolved, it will affect the nurse's ability to be licensed in another state.

Medicaid and Medicare Exclusion Lists

The state board may also report license discipline to other agencies such as the Office of the Medicaid Inspector General. This office can then place the nurse on a disqualified or excluded provider list, which means the nurse cannot work for any employer who receives Medicaid reimbursement. A similar process at the federal level may exclude the nurse from participation in employment funded by the federal Medicare program. This can render the nurse almost unemployable, as disqualification from participation in these programs would apply to almost all employment situations. Placement on the provider-disqualified list may make it difficult to obtain employment in another state, or even from obtaining a license in another profession (Brous, 2012).

National Practitioner Data Banks-NPDB and Former HIPDB

The National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB) was established by Congress in 1990 as a national repository of information that employers and healthcare agencies can consult when reviewing practitioners' credentials. Its purpose is to protect the public and promote public safety by preventing unethical or incompetent practitioners from moving from state to state without disclosure of their past history. This includes physicians, nurses, and other practitioners. The data bank serves as a flagging system to facilitate a more thorough review of professional credentials. Reporting is required by professional regulatory boards that take adverse licensure actions against individuals or hospitals that deny clinical privileges (this could apply to advanced practice registered nurses [APRNs]). Individuals (including insurance companies) making payment as a result of a medical malpractice action or claim (including nurses) must also report the practitioner to the NPDB. Settlements of claims are included as reportable. The data bank can be queried by state licensing boards, hospitals, or other healthcare entities that have entered into or may be considering entering into employment or affiliation relationships with the healthcare practitioner. A plaintiff's (the person who initiates the lawsuit) attorney also has access if a malpractice action has been filed and the person inquired about is named in the suit. NPDB queries are mandatory for hospitals when a practitioner applies for medical staff privileges as part of an ongoing credentialing process. The information in the NPDB is for the specified purposes only and is subject to fines if improperly disclosed or used. The general public is not permitted access to the NPBD.

The Healthcare Integrity and Protection Data Bank (HIPDB) was established by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, Public Law 104-191. The purpose of the HIPDB was to help combat healthcare fraud and abuse. The HIPDB is no longer operational; however, information previously collected and disclosed by the HIPDB is now collected and disclosed by the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB). The NPDB and the HIPDB were established for different purposes, and overlap existed in some reporting and querying requirements. To eliminate this duplication, the information from the databases was combined. Although the HIPDB no longer exists as a separate Data Bank, there is a historical reference page for HIPDB information at the NPDB website. A guidebook for the NPDB is available online (HRSA, 2018).

Because there are many implications of nurses being reported to the NPDB, any nurse involved in a legal action is urged to consult with an attorney who is familiar with outcomes that can have serious effects on employment and professional reputation. These attorneys may be able to advocate on the nurse's behalf to avoid being reported, or minimize the effects of being reported. This includes not only licensure actions, but also criminal or in some instances civil actions. The American Association of Nurse Attorneys (TAANA) offers a list of nurse attorneys familiar with licensure defense, and who have expertise related to implications of other legal actions on nurse licensure. (Consult http://www.taana.org for further information.)

Private or “Off-Duty” Conduct ⬆ ⬇

Many nurses mistakenly believe that anything they do off duty will not affect their nursing licensure status. Because the BON is mandated to protect the public, off-duty conduct may become relevant to nursing practice in some instances. For example, driving under the influence (DUI), use of recreational or illegal drugs, accusations of child or elder abuse, violation of restraining orders, writing bad checks, or conduct that reflects dishonesty or questionable judgment may become relevant to public safety. Some boards of nursing can compel nurses to undergo substance use evaluation at their own expense in order to determine fitness to practice. This is so even when there has been no allegation of impaired practice, when the issue has arisen over off-duty conduct (Brous, 2012). Usually, board action is based on a pattern of questionable conduct, but it could be based on a particularly egregious incident. The board has wide latitude to seek information that may be relevant to the practice of safe nursing. Additionally, failure to make child support payments, to pay taxes, to repay student loans, or to pay one's creditors may create licensure problems for nurses. A nurse's moral character is at issue when criminal activity is involved. Some states require licensees to self-report any misdemeanors, felonies, and plea agreements. A licensee in such a position should consult an attorney who is familiar with state board processes before any plea agreement is entered into (Brous, 2012). In recent years, many state boards have received complaints related to misuse of social media, including patient confidentiality breaches, harassment, bullying, and boundary violations that have resulted in disciplinary action. All of these behaviors reflect poorly on the nurse's character and may subject the nurse to ethics or unprofessional conduct charges.

Remediation ⬆ ⬇

Remediation has been suggested for some nurses who perform incompetently and make mistakes as an alternative to, or in addition to, licensure actions by the state board of nursing. The goal of any remediation program is to ensure safe nurses in the workforce by increasing competency necessary to prevent practice breakdowns. For example, Texas implemented an innovative program named the Knowledge, Skills, Training, Assessment, and Research (KSTAR) Nursing Pilot Program in 2014 (Matthews et al., 2019). The program includes collaborative practices among regulatory, practice, and educational entities and uses novel, individualized approaches to correct nursing practice breakdown (NPB) (Matthews et al., 2019). Assessment, coaching and simulation processes are included. The authors include a KSTAR Nursing Program Process Map that outlines steps to achieve benchmarks for competency, or to identify areas which may require further remediation. As part of the process, nurses complete a 6-hour nursing jurisprudence and ethics course where a reflective exercise helps them consider the ethical-legal implications related to the NPB. Following a 2-year pilot study, 92% of participants successfully completed the program, with no significant difference in recidivism at 24 months after program completion when compared with nurses completing traditional remediation programs. Based on these successful outcomes, the program may serve as a model for individualized remediation programs for nurses by other state boards (Matthews et al., 2019).

Civil Actions ⬆ ⬇

Civil actions deal with disputes between individuals. Civil law is designed to monetarily compensate individuals for harm caused to them. Nurses can become involved in civil actions, such as malpractice actions, personal injury lawsuits, and workers' compensation, or employment disputes, such as wrongful discharge. Nurses also can become involved as witnesses for a patient's personal injury case against another person. Workers' compensation laws prevent employees from suing their employers for injuries received on the job. The cost of the injury and lost wages due to the injury must be settled through the workers' compensation benefits plan the employer provides for the employees. Worker's compensation serves as the exclusive remedy for the employee, with certain exceptions. This means that workers cannot file an additional civil claim for monetary damages due to the injury.

Malpractice is the negligent conduct of a professional. It is defined by (1) duty-established by a professional relationship; (2) breach of duty-an act of commission or omission in violation of the nursing standard of care; (3) a physical injury; and (4) causation-the nurse's breach of duty caused the plaintiff's injury, sometimes called proximate cause. All four of these elements must be present and proven for the plaintiff to prevail. Even in the face of negligent acts by the nurse, the plaintiff must prove that the nurse's act caused the injuries. Therefore, even if a nurse commits an error in patient care, it may not result in any liability for the nurse when all of these elements are not met. An example is when a nurse gives the wrong medication to the patient, but there is no adverse outcome or injury as a result of the error.

In Charash v. Johnson (2000), a Kentucky appeals court found that the hospital was short staffed, but the plaintiff's estate failed to prove that it was related to the plaintiff's death. Likewise, a nurse who attempted four times to start an intravenous (IV) line, contrary to hospital policy to make only two attempts, was not liable for the patient's nerve damage, because the plaintiff was unable to prove the causal connection (Coleman v. East Jefferson General Hospital, 1999).

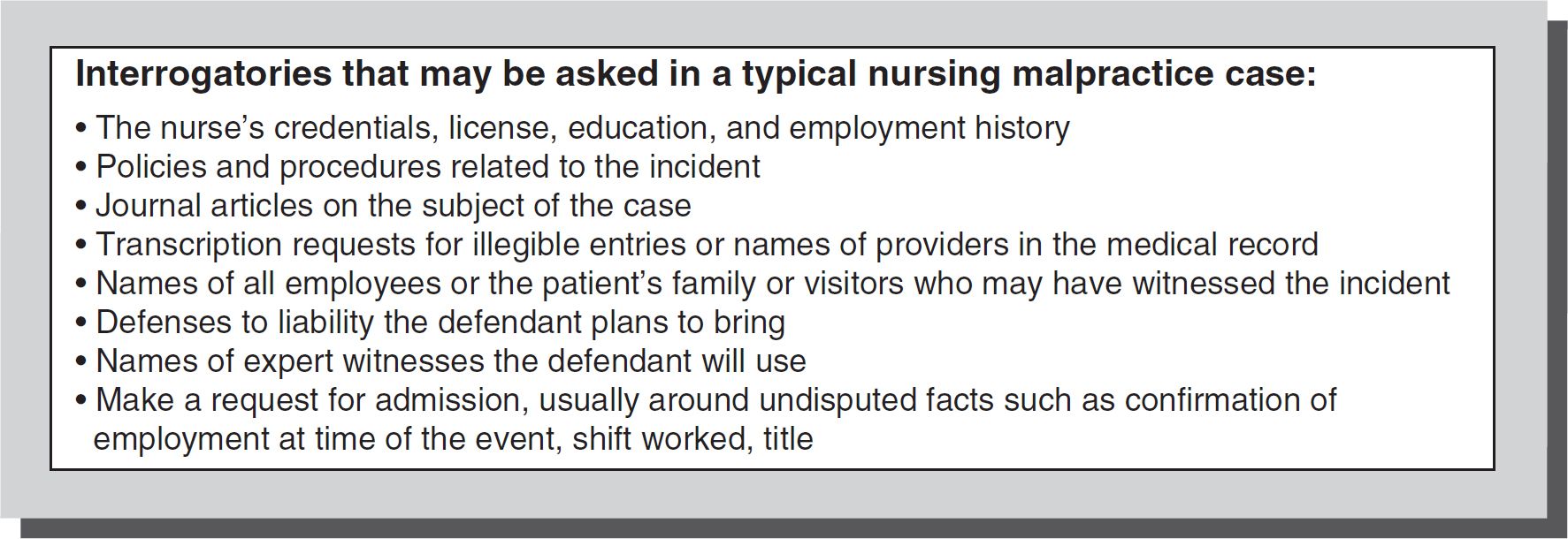

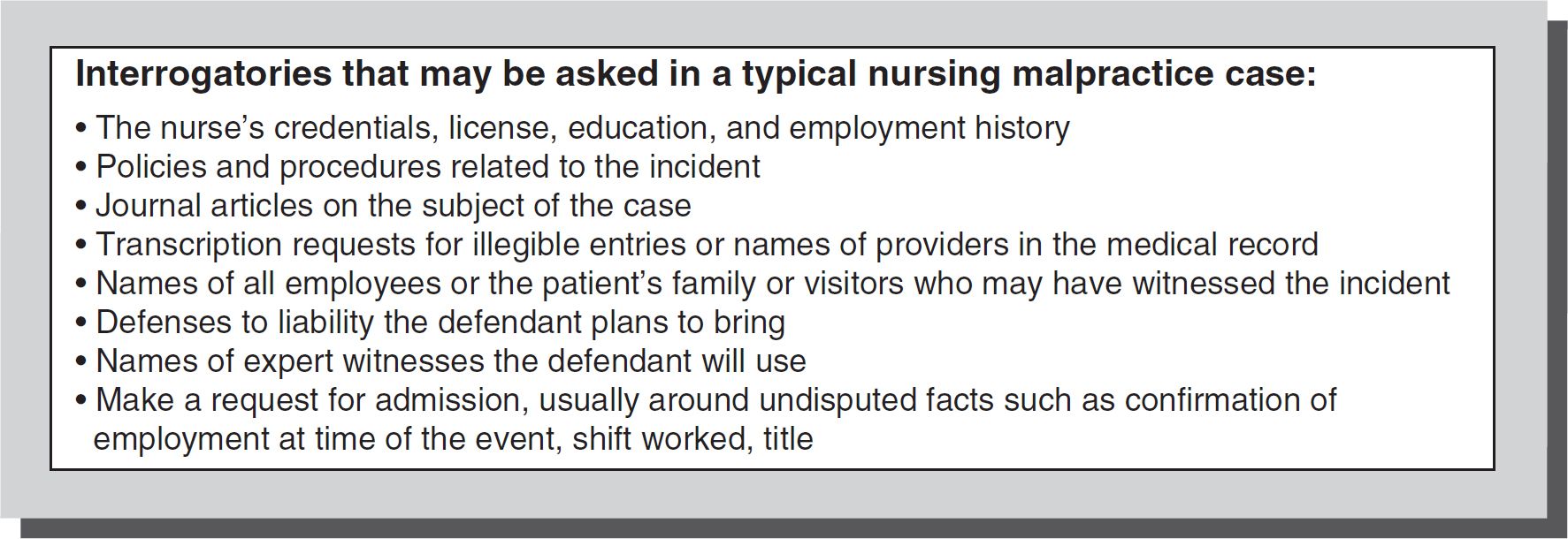

Most plaintiffs will hire a lawyer to pursue a malpractice claim. To establish the claim, pertinent medical records and opinions of expert witnesses (nurses with experience in the same field of nursing who will testify as to the standard of care) will be obtained to support the allegations of malpractice. The parties then exchange information (discovery phase) about the plaintiff's claims of negligence and damages (injury and any costs incurred due to the injury) and the defendant's defense to such claims. Discovery is done through interrogatories, requests for production, and depositions. An interrogatory is a document filed with the court in which one party asks questions of the other (see Figure 3-4). A request for production is a request in which one party asks the other to produce documents for the requesting party, such as medical records, operating room logs, or even specimen logs. The requesting party can use these documents to learn more facts about the case or identify potential witnesses to the event being litigated. The defendant nurse may also be required to give deposition testimony. A deposition is a legal proceeding where questions are asked and answered under oath and recorded by a stenographer. The deposition testimony can be used later in a trial.

Figure 3-4 Typical interrogatory questions.

© Jones & Bartlett Learning

When the discovery phase is complete, the case will either settle or proceed to trial. Any money paid to the plaintiff may come from the nurse's malpractice insurance policy or from the nurse's assets if the judgment amount exceeds the policy amount, the nurse is uninsured, or the malpractice carrier has denied coverage. For example, malpractice coverage is denied when the nurse acted outside the scope of employment.

Impact of Malpractice ⬆ ⬇

The emotional impact of malpractice and adaptive coping for nurses named as defendants is an often overlooked aspect of the malpractice process. The public nature of the discipline creates embarrassment and shame, which can lead to depression and a lack of self-confidence required for return to practice (Brous, 2019). The cumulative effect of being disciplined by multiple boards of nursing (BONs), along with other regulatory agencies, can compound the stress and demoralization. The potential collateral consequences can create financial strain and emotional trauma that is long-lasting. Interventions identified as helping nurses cope include finding and educating an attorney about nursing practice and standards and working with a licensed counselor with whom the nurse would have client-provider privilege to maintain confidentiality. Nurses also need to be active participants in the process, and not just passive recipients of what is happening. Emotional support of the nurse is vital, because there may be limited or no information that can be shared about the process with peers or others. Nurses are most often cautioned not to talk to anyone about the lawsuit except with their attorney. Conversations with others can be subject to deposition testimony.

Even if the nurse is dismissed from the lawsuit at some point or found not liable, the process is lengthy, emotionally and physically draining, and can have lasting outcomes. Often, nurses' self-esteem and self-confidence are eroded as others have questioned the integrity of their practice, even if later exonerated. Sometimes nurses who have gone through the malpractice process can assist others who have been sued by providing valuable education and support.

References ⬆ ⬇

- American Nurse Journal Staff. (2022). Radonda Wright sentenced to three years of supervised probation. American Nurse. https://www.myamericannurse.com/radonda-vaught-case-where-do-things-stand/

- Brous , E. (2012). Common misconceptions about professional licensure. American Journal of Nursing, 112, 10, 55-59.

- Brous , E. (2019). The BON Discipline Cascade. American Nurse. https://www.myamericannurse.com/the-bon-discipline-cascade/

- Charash v. Johnson, Ky. App. LEXIS, 42 (April 21, 2000).

- Coleman v. East Jefferson General Hospital, 742 So.2d 1045 (La. App. 1999).

- Health Resources and Services Administration. (2018). NPDB guidebook: National practitioner data bank. HRSA. https://www.npdb.hrsa.gov/resources/NPDBGuidebook.pdf

- Larson , K., & Elliott , R. (2010). The emotional impact of malpractice. Nephrology Nursing Journal, 37(2), 153-155.

- MacLean v. Board of Registration in Nursing, 458 Mass. 1028-Mass: Supreme Judicial Court (2011).

- Matthews , D., Benton , K., Moreland , S. C., & Wagner , T. (2019). Addressing nursing practice breakdown: An alternative approach to remediation. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 10(1), 28-34.

- National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (n.d.). HIPDB Archive.https://www.npdb.hrsa.gov/resources/hipdbArchive.jsp

- Nevada State Board of Nursing v. Merkley, 940 P.2d 144 (Nev. 1997).

- Stephens v. Pennsylvania Board of Nursing, 657 A. 2d 71 (Pa. 1995).

- Westin v. Shalala, 845 F.Supp. 1446 D. (Kan. 1999).

Additional Resources ⬆