Information ⬇

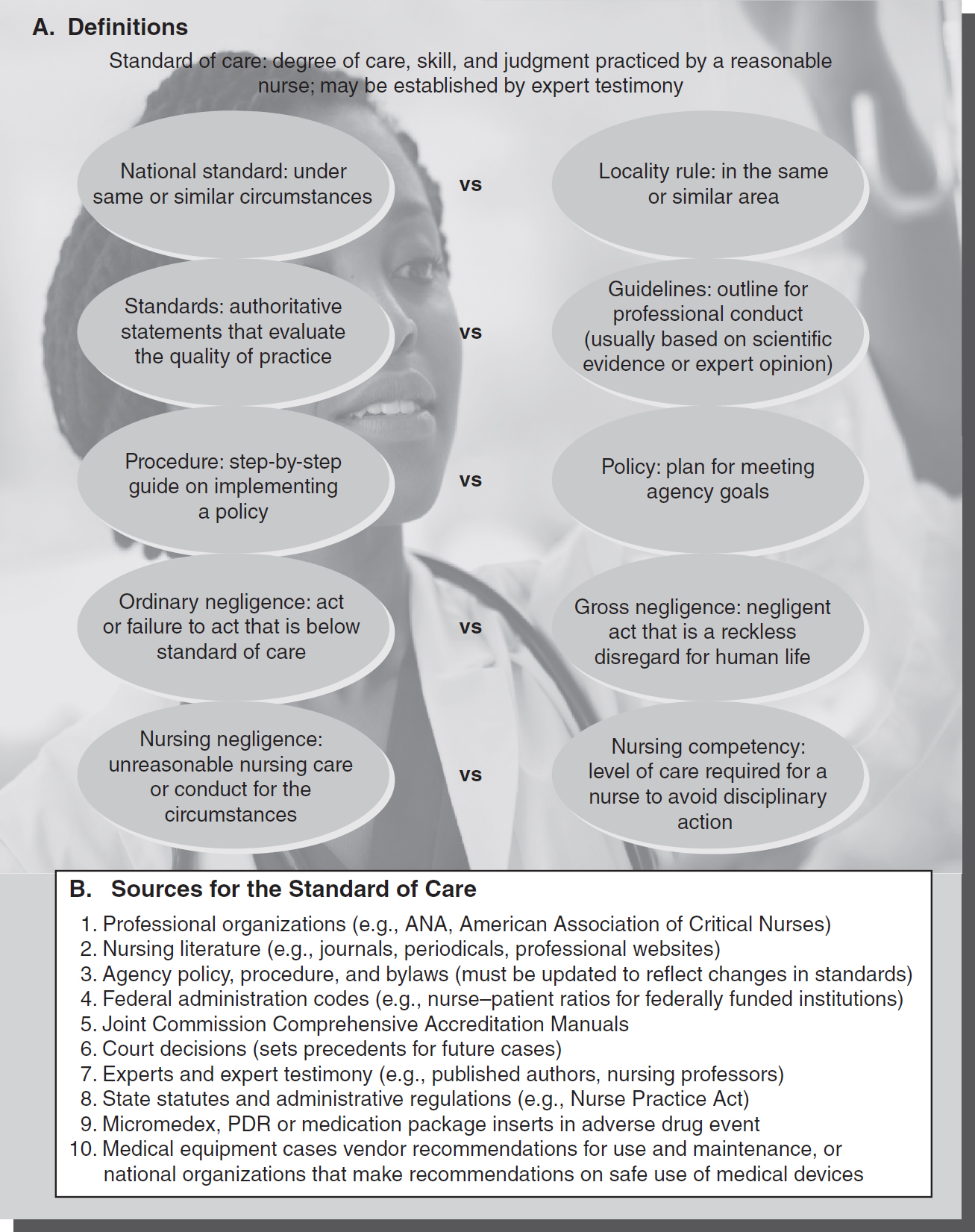

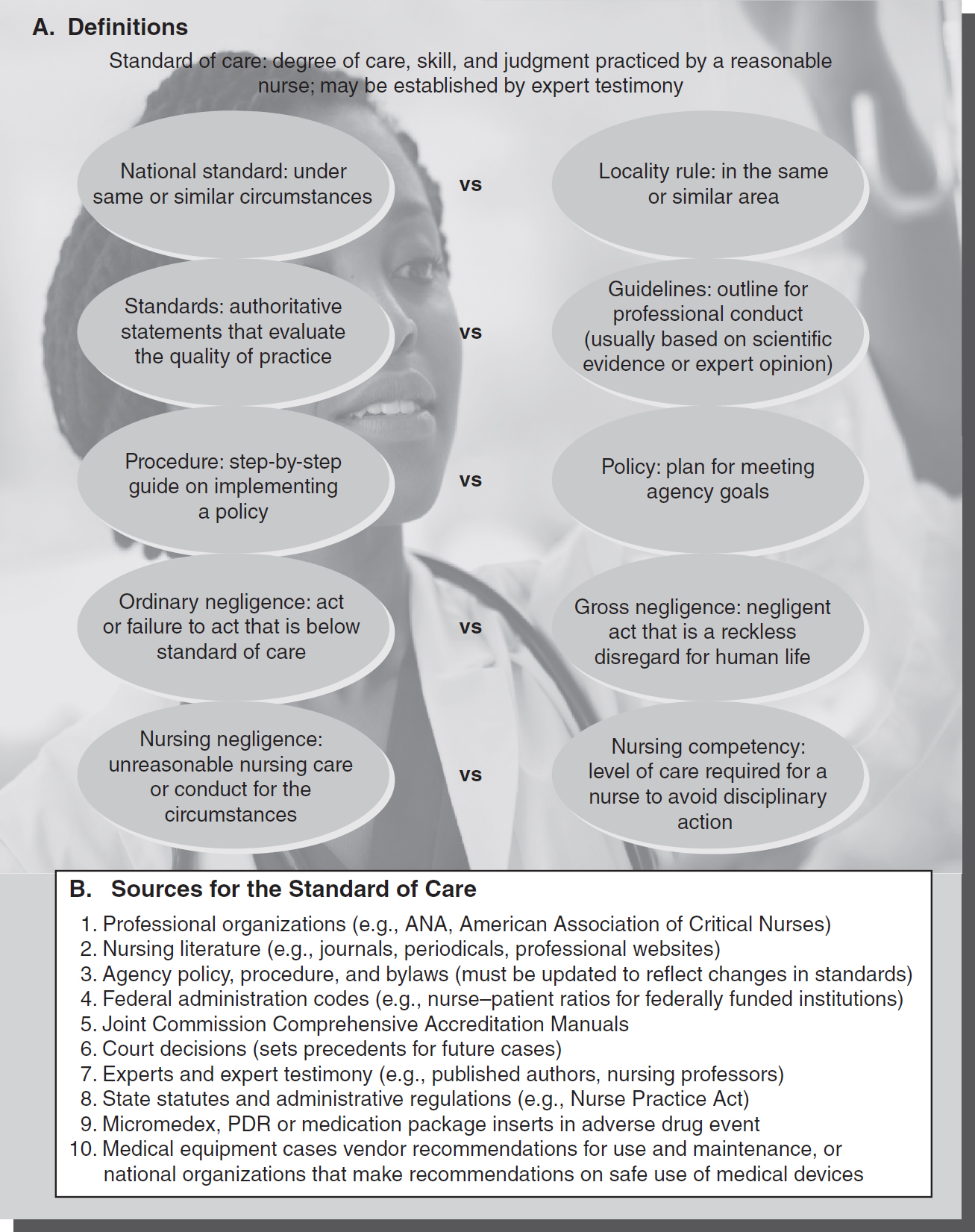

Figure 4-1 Definitions and sources for the standard of care.

© Jones & Bartlett Learning; © francisblack/iStockphoto.com

In most states, the professional standard of care is defined by statute or case law. Nurses can be liable for nursing negligence in a civil court when they breach the standard of care. They also can face the restriction or revocation of their nursing license in an administrative proceeding by the licensing board. Having a definition of the standard of care gives a clearer view of when nursing negligence has occurred and allows the injured party to be compensated for the harm done. It also allows the nurse to avoid a nursing malpractice claim when a bad result occurs despite due care by the nurse.

National Standard of Care Versus the Locality Rule or Community Standard ⬆ ⬇

The national standard of care (see Figure 4-1A) is the degree of care, skill, and judgment exercised by a reasonable nurse (a reasonably prudent nurse) under the same or similar circumstances. A nurse has the duty to practice nursing using the applicable standard of care. This does not require the nurse to render optimal care or even possess extraordinary skill. Likewise, the rule that a nurse must exercise best nursing judgment does not necessarily hold the nurse liable for an error in nursing judgment. However, the nurse's error in judgment must not be below the standard of care. Even good nursing care does not guarantee the patient a good result.

The locality rule (sometimes called the community standard) holds that a nurse must practice with the degree of skill and care possessed by other nurses in the same or similar area (locality or community). How a nurse in a rural emergency department performs will be compared to nurses in other rural areas. The locality rule is followed in a minority of states.

The national standard of care holds a nurse in a rural community hospital to the same standard of care as a nurse in a metropolitan medical center, given the similarity of the situation. The national standard typically does not take into consideration that the emergency department at a metropolitan medical center has more resources and technology than a rural emergency department, depending on the circumstances of the case. For example, standards for treating a heart attack would be the same at all emergency rooms following national standards of care. The majority of states follow the national standard. The national standard (or locality rule or community standard in a minority of states) is used in a malpractice civil action. However, in Bates v. Dodge City Healthcare Group (2013) the court used both the national standard and the community standard when analyzing a nurse's conduct in a malpractice and professional liability case. In 1996, nurse Unruh admitted plaintiff Entriken to the obstetrics department of Western Plains Regional Hospital in Dodge, Kansas. Entriken began to have signs of “prolonged decelerations to the fetal heart rate,” so the nurse immediately called the physician to report this and to request that he come to the hospital. Ten minutes later the nurse paged him “stat” after he had not yet arrived. Nurse Unruh testified that the physician lived 5-10 minutes from the hospital and in her experience he responded promptly when called. When the physician arrived 28 minutes after the nurse's call about the fetal decelerations, he ordered an immediate C-section. The baby was delivered but did not breathe for 5 minutes after birth. She was flown to a medical center for treatment in the neonatal intensive care unit, but was left with cerebral palsy, severe spastic quadriplegia, and a seizure disorder. The parents then brought a lawsuit against the hospital alleging negligence in the failure of nurse Unruh to follow the standard of care. Specifically, the plaintiff's alleged that the nurse did not activate the chain of command and appropriately contact her supervisor and the C-section team while waiting for the physician to arrive. Expert testimony for both the plaintiff and defendant hospital agreed that the national standard of care applied to most of the nurse's actions, such as interpreting fetal monitor tracings, performing patient assessment, and communicating with physicians, but there was disagreement as to whether the national standard or the community standard (or locality rule) should apply to initiating the chain of command. If the community standard was applied, then nurse Unruh's conduct would be compared to “the same or similar communities” where there were less resources and available obstetric physicians. In fact, the defendant hospital only had two obstetricians on staff as compared to approximately one hundred obstetricians at major medical centers, where some of the plaintiff's experts practiced, thus making the available resources different in these communities. The Supreme Court of Kansas affirmed the district court and appeals court decisions to allow the community standard to be applied to the case on the question of the chain of command. The court noted that even if the nurse had implemented the chain of command, the lack of available resources (in this and comparison communities) could have meant that the outcome for the baby would not have been any different. By the court not applying the national standard on this point of care, the parents lost the case against the hospital as based on the nurse's conduct. This case clearly illustrates the differences in outcome that can occur as a result of applying either a national standard or a community or locality rule standard in malpractice cases.

In contrast, a nursing board disciplinary action looks for a nurse's level of competency. State regulations define the level of competency required of a nurse. Falling below the level of competency can result in a disciplinary action by a state board even when no harm was done to a patient.

How the Standard of Care Is Applied ⬆ ⬇

A nurse is liable for nursing malpractice when the nursing standard of care is not followed. As the definition implies, the standard for nursing conduct varies in each situation. For example, an emergency department nurse draws blood from a 45-year-old woman. The nurse does not put the side rails up on the stretcher. The nurse then walks away to send the blood to the lab, while the woman faints and falls from the stretcher. The patient sues the nurse for negligence based on the patient fall. Both parties to the suit admit expert testimony and the emergency department's policy and procedure manual. The emergency department manual states that side rails must be used for all children, older adults, and patients who are confused or unconscious. Expert testimony confirms that side rails are often necessary for children and older adults because patients in these age groups fall from stretchers more frequently and are injured severely even from minor falls. The jury may determine that the nurse did not violate the standard of care in that situation because the nurse had no indication that the patient was at risk for falling.

Under these same facts, if the patient is 80 years old, the situation and outcome changes. Now the nurse does have some indication that the patient is at risk for falling, and the standard of care changes for that situation. Most likely, the nurse would be found to have breached the standard of care required for this situation.

The standard of care is not a cookbook of step-by-step ways to conduct oneself professionally in any given situation. It requires the nurse to be aware of any harm that may befall the patient and to take reasonable steps to prevent that harm. The standard of care comes from many sources (see Figure 4-1B). The nurse is accountable to know the standard as developed through multiple authoritative sources, and to keep up with changes within the profession that reflect current standards of care.

Failure to meet standards can be grounds for licensure discipline actions in addition to civil negligence or malpractice lawsuits. For example, the method a nurse used in holding NICU infants (under the arms and dangling or by the back of the neck) caused her license to be revoked. The standards used by the board were established by the standards of the professional organization and certification standards for that specialty (Mississippi Board of Nursing v. Hanson, 1997).

Nurse Practice Act ⬆ ⬇

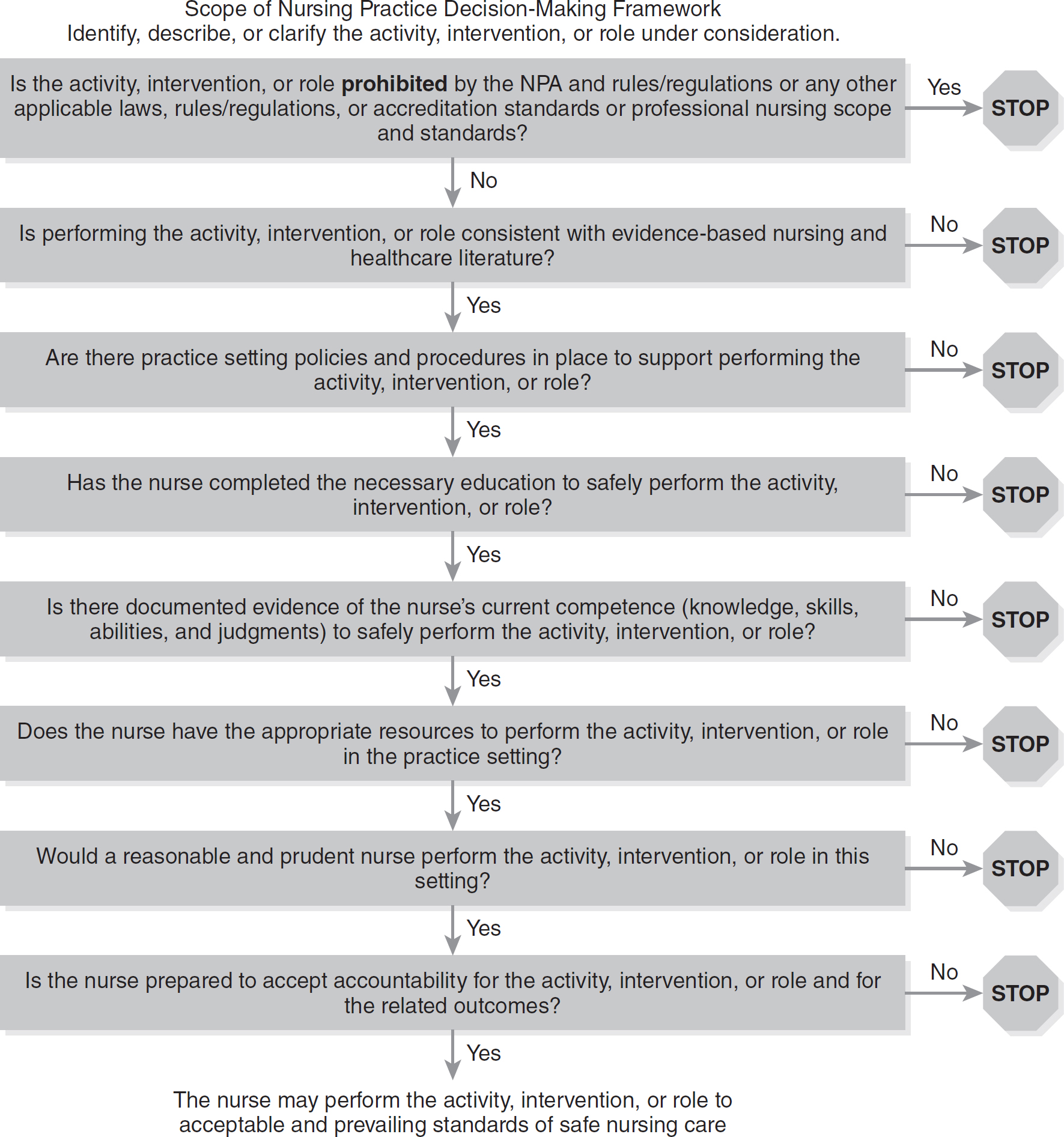

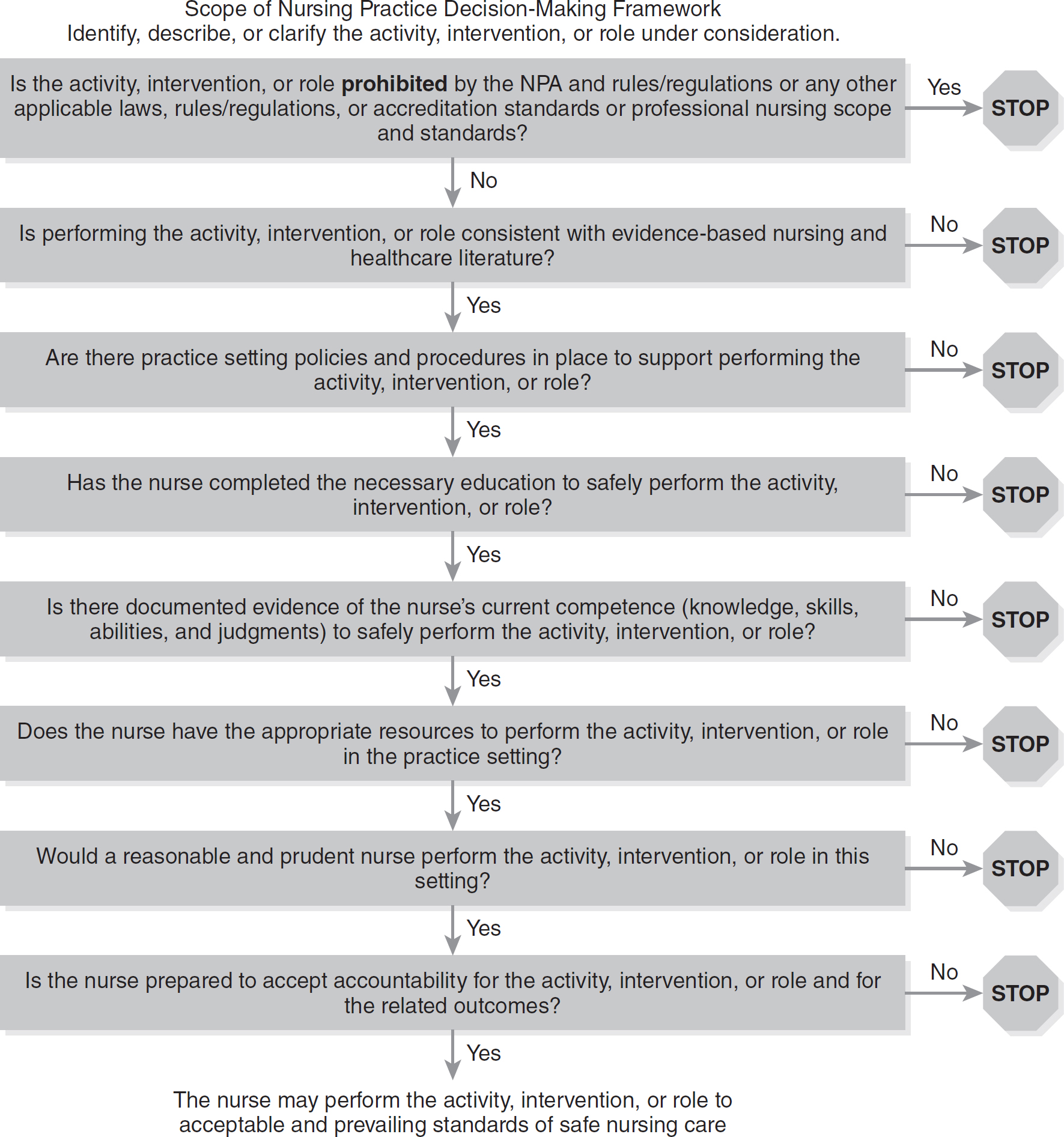

Each state has a nurse practice act (NPA) that defines the practice of nursing and determines whether nurses stay within their scope of practice. The scope of practice varies in each state. An agency's policies and procedures must not expand the scope of nursing practice. Figure 4-2 shows how a decision-making framework can be used in deciding whether an activity is within the scope of nursing practice. This uniform model was developed using an expert panel from the Tri-Council of Nursing in collaboration with the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) (Ballard, 2016). This NCSBN model has been adopted by some state boards of nursing.

Figure 4-2 Determining scope of practice.

Reproduced from Ballard, K., Haagenson, D., Christiansen, L., Damgaard, G., Halstead, J. A., Jason, R. R., … Alexander, M. (2016). Scope of nursing practice decision-making framework. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 7(3), 19-21. doi:10.1016/s2155-8256(16)32316-x

Standards of Care in Specialties ⬆ ⬇

Specialists are held to the standard of other similarly situated specialists. The conduct of a nursing specialist, such as a pediatric nurse practitioner, will be compared to that of other similarly situated pediatric nurse practitioners. When specialists have the responsibility of the same procedure, some states allow each specialist to be an expert on the standard of care for the particular procedure. For example, in a malpractice action against a pediatric nurse practitioner, a nurse-midwife may explain to the jury the standard of care in neonatal resuscitation, because both types of nurses may perform that procedure under their state's NPA.

Majority Versus Minority Views ⬆ ⬇

There is a generally recognized course of treatment for each diagnosis within each specialty. The phrases “schools of thought,” “best medical judgment,” and “respectable minority” recognize that within each specialty there are alternative treatments for each diagnosis that are professionally acceptable to meet the standard of care.

Expert Witnesses ⬆ ⬇

Nursing malpractice is a professional negligence suit that typically requires an expert opinion as to the standard of care within the nursing profession and how it was breached. Therefore, expert nursing testimony in case law establishes the standard of care in that set of circumstances. The issue of physicians acting as experts on nursing standards was addressed by the Illinois Supreme Court. The court ruled that only a nurse is qualified to establish the standards for the nursing profession (Sullivan v. Edward Hosp., 2004).

Accreditation/Professional Standards ⬆ ⬇

Accrediting bodies, such as The Joint Commission, have set standards for practice in accredited institutions. Effective communication among the healthcare team and with patients is just one example of a standard set by The Joint Commission. The need for all patients to participate in their own healthcare decisions requires effective communication, including providing information that is appropriate to the patient's age, understanding, and language. Therefore, elements of performance (standards) include a needs assessment that addresses learning abilities and cultural beliefs. As with most requirements in accreditation, self-evaluation must be performed by collecting data on the patient's perception of care (patient satisfaction surveys) to address the patient's healthcare education needs. Initial orientation and ongoing staff training in communication and cultural diversity must be in place for compliance.

Professional standards such as those set by the American Nurses Association (ANA) and other specialty nursing organizations will also be consulted in determining the standard of care in a particular situation. The ANA publishes current standards for general and specialty practice by nurses (ANA, 2021). The Infusion Nurses Society (INS), for example, publishes standards and best practices for starting intravenous lines (IVs) that would apply to this practice intervention as part of the standard of care. The ANA (2015) Code of Ethics for Nurses is another example of professional standards for nurses' conduct.

References ⬆

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. Silver Springs, MD: ANA.

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). Silver Springs, MD: ANA.

- Bates v. Dodge City Healthcare Group, 296 Kan. 271; 291 P.3rd 1042; 203 Kan. LEXIS 3 (2013).

- Mississippi Board of Nursing v. Hanson, 703 So.2d 239 (Miss. 1997).

- National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN). (2016). Scope of decision-making framework. https://www.ncsbn.org/public-files/2016_Decision-Making-Framework.pdf

- Sullivan v. Edward Hosp., 806 N.E.2d 645 (Ill. 2004).