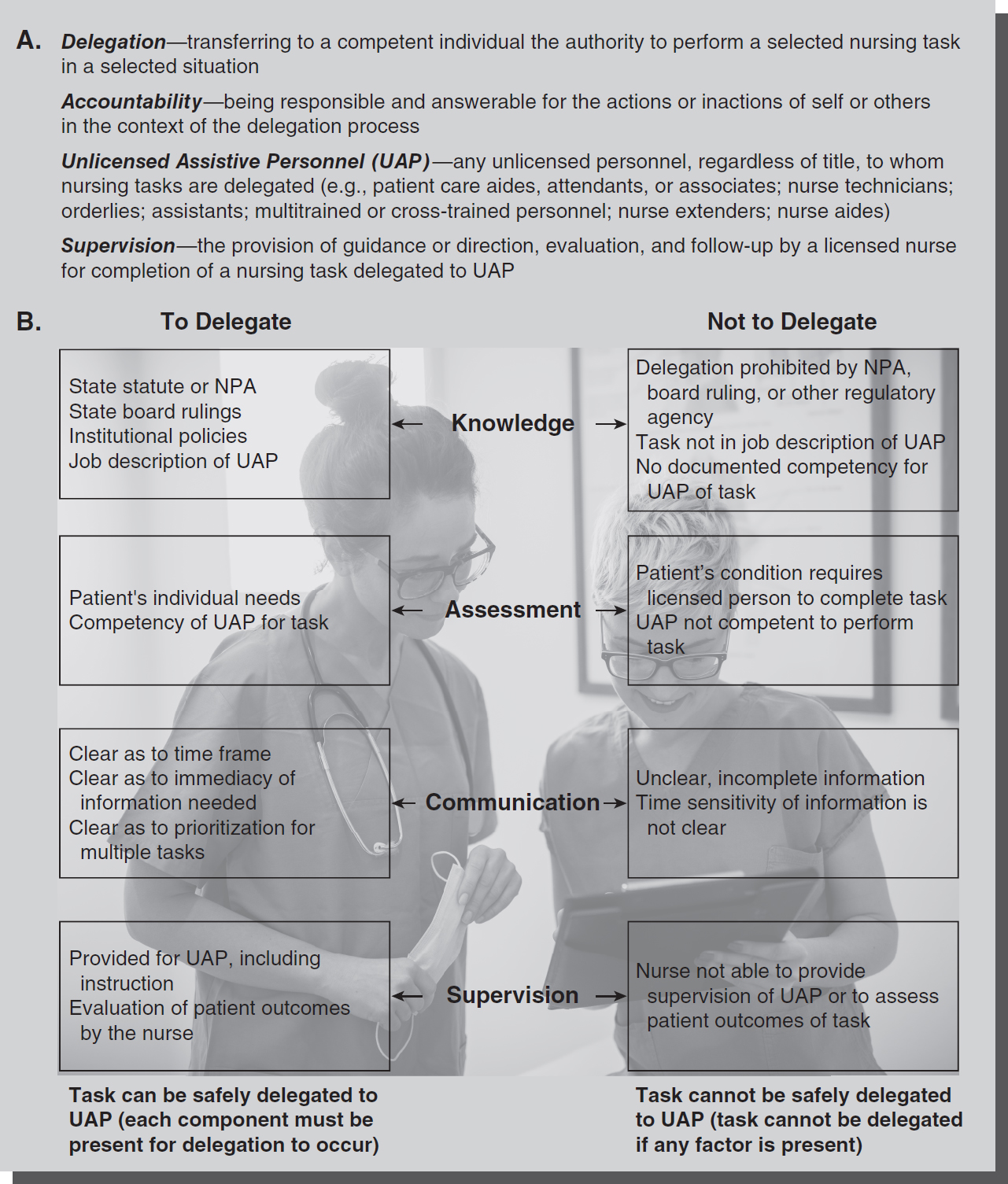

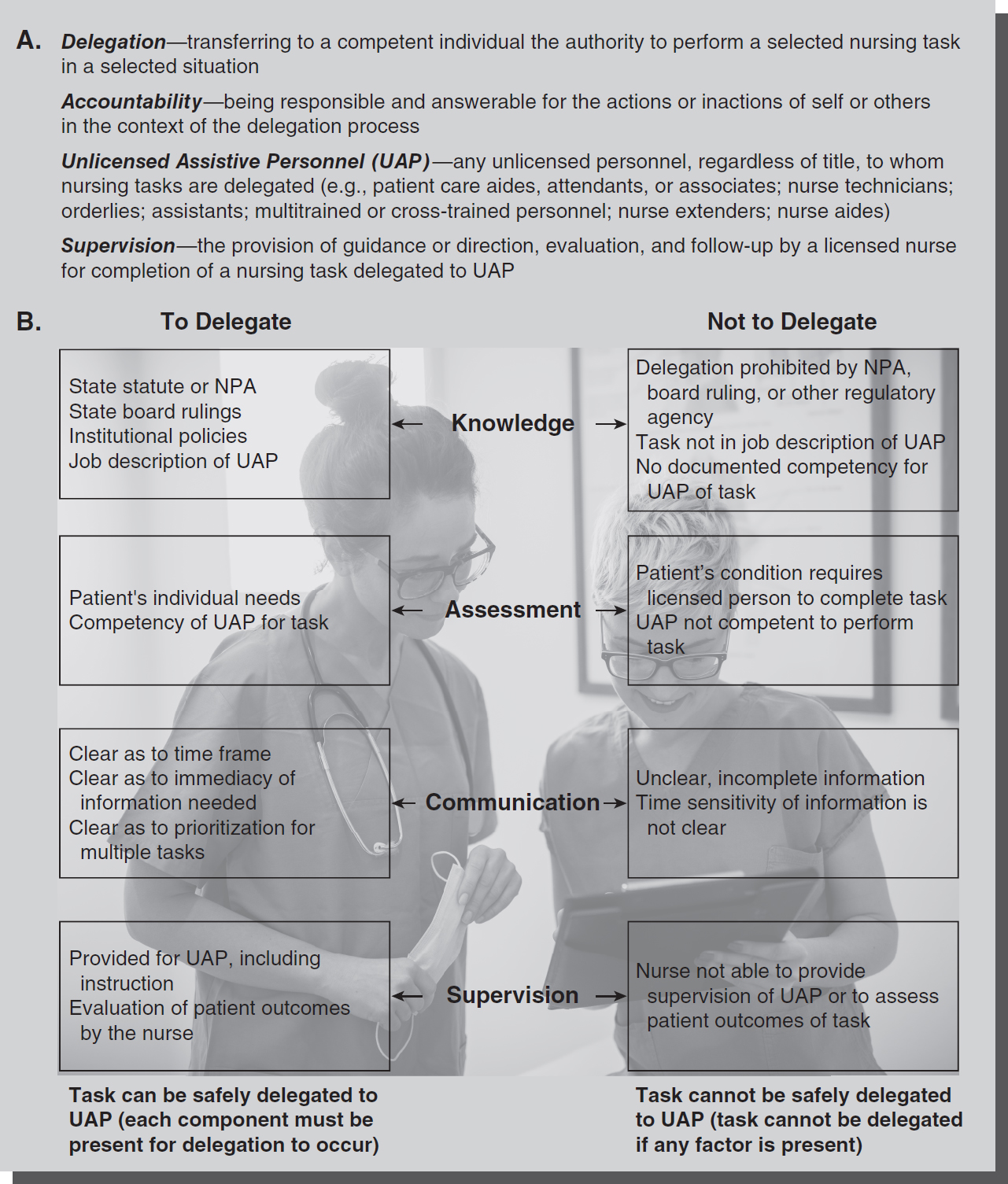

Figure 10-1 Key points in delegation to UAP.

© Jones & Bartlett Learning; © Dusan Petkovic/Shutterstock

Effectively working with assistive personnel to implement the nursing process is a necessary and continuing part of nursing practice. Optimum use of all levels of personnel is needed to meet financial and other constraints in healthcare settings. As the licensed caregiver, the nurse is responsible and accountable for the quality of care that patients receive. The nurse may delegate or assign tasks to an unlicensed caregiver, but accountability in terms of outcomes for the patient is retained by the nurse. Unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP) act for the nurse in implementing selected patient care activities but do not act in place of the nurse. The critical thinking, professional judgment, and decision making by the nurse can never be delegated. See the definitions in

Figure 10-1A.

The first frame of reference to ensure proper delegation (see Figure 10-1B) is the statute or nurse practice act (NPA) that defines the scope of practice for nurses in a particular state. These statutes generally follow the model set forth by the American Nurses Association (ANA), which defines the practice of nursing by a professional nurse as the process of diagnosing human responses to actual or potential health problems, including supportive and restorative care, health counseling and teaching, case finding and referral, and collaborating in the implementation of the total healthcare regimen. The definition set forth in the statute limits what the nurse can delegate by defining what is nursing practice.

Other authoritative references include any state board rulings on the use of UAP and position papers from the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) or the ANA. The NCSBN and ANA (2019) issued a “Joint Statement on Delegation” that reviews terminology, policy considerations, principles, and resources for delegation. The core philosophy of this document is that delegation is an essential skill for nurses, the delegation decision remains with the nurse, and patient safety is the paramount consideration. According to the joint statement, there is both individual accountability and organizational accountability for delegation. A person to whom the delegation is given (known as the delegatee) can be an RN, LPN/VN (licensed practical nurse of vocational nurse), or AP (assistive personnel-previously referred to as a UAP or unlicensed assistive personnel). The NCSBN and ANA joint statement (2019) summarizes and states the following:

- A delegatee is allowed to perform a specific nursing activity, skill or procedure that is outside the traditional role and basic responsibilities of the delegatee's current job.

- The delegatee has obtained the additional education and training, and validated competence to perform the care/delegated responsibility. The context and processes associated with competency validation will be different for each activity, skill or procedure being delegated. Competency validation should be specific to the knowledge and skill needed to safely perform the delegated responsibility as well as to the level of practitioner (i.e., RN, LPN/VN, AP) to whom the activity, skill or procedure has been delegated. The licensed nurse who delegates the “responsibility” maintains overall accountability for the patient. However, the delegatee bears the responsibility for the delegated activity, skill or procedure.

- The licensed nurse cannot delegate nursing judgment or any activity that will involve nursing judgment or critical decision making.

- Nursing responsibilities are delegated by someone who has the authority to delegate.

- The delegated responsibility is within the delegator's scope of practice.

- When delegating to a licensed nurse, the delegated responsibility must be within the parameters of the delegatee's authorized scope of practice under the NPA. Regardless of how the state/jurisdiction defines delegation, as compared to assignment, appropriate delegation allows for transition of a responsibility in a safe and consistent manner. Clinical reasoning, nursing judgment and critical decision making cannot be delegated. (NCSBN, 2019, p. 2-3)

Also according to the NCSBN (2019), the licensed nurse must be responsible for determining patient needs and when to delegate, ensure, and to evaluate outcomes of and maintain accountability for delegated responsibility. Finally, the delegatee must accept activities based on their competency level, maintain competence for delegated responsibility, and maintain accountability for delegated activity.

Organizational accountability for delegation relates to providing sufficient resources and promoting a work environment for proper delegation, as well as having clear policies and procedures regarding delegation and the processes to evaluate them.

Similarly, the ANA (2015) Code of Ethics for Nurses provides guidance for nurses when delegating tasks to other healthcare workers. Central to the code is the idea that the nurse retains accountability for the delegated task. Also specified is that nurses who are in management and administrative roles are responsible to maintain an environment that helps nurses develop skills related to delegation and supports proper delegation, including policies, job descriptions, and competency validation for UAP.

The nurse uses critical thinking and professional judgment in deciding when delegation is appropriate. Delegation occurs on a case-by-case basis, with the nurse assessing the individual patient's needs and circumstances. It is not a to-do list for certain job classifications and is a process that needs ongoing assessment and evaluation of factors, such as complexity of the task, stability of the patient's condition, predictability of outcomes from the intervention, and the abilities of the staff to whom the task will be delegated. There are many positive benefits of delegation, including opportunities for leadership, instruction, team building, and mentoring staff members. In addition, the nurse is given time to perform more skilled nursing functions consistent with role expectations. The NCSBN also considers that the organization must provide the environment and support for nurses for effective delegation in terms of sufficient resources, policy development, competency validation of UAP, and the skill mix of staff members. Proper and effective delegation involves (1) the right task, (2) the right circumstances, (3) the right person, (4) the right direction/communication, and (5) the right supervision. In all situations, the nurse's professional judgment and critical thinking determine what can be delegated safely to UAP or others.

Delegation remains an underdeveloped and sometimes confusing skill among nurses, and one that is difficult to measure. Successful delegation relies on such factors as personality, communication style, and cooperation on the part of the nurse and the UAP. The success or failure of delegation depends on a positive two-way relationship of mutual respect and trust between the nurse and the UAP who assumes responsibility for specific tasks. This dynamic exchange between the nurse and the UAP requires constant evaluation, feedback, and modification to achieve the results needed to meet patient care needs and safety.

In an effort to save costs, or as a result of understaffing, organizations may inappropriately pressure nurses to delegate to UAP in questionable circumstances. Nurses are cautioned to continue to follow professional and practice guidelines to avoid unnecessary exposure of a patient to harm, and to fulfill legal obligations related to responsible delegation. State boards of nursing can be queried about delegation questions or dilemmas, and some have clarified recurring delegation issues in state-board publications. For example, Lanier and Morris (2017) published an independent study article to enhance skills of nurses in the delegation process as based on professional standards and Ohio statutes. Case studies and analysis regarding delegation situations are presented.

Improper Delegation and Nurse Liability

The nurse can be liable for improper delegation in several circumstances. One example is when a task that should not be delegated (e.g., medication administration) is assigned to UAP. Another example is when the nurse delegates a task to UAP who are not competent to perform the task. While nurses can generally rely on documented competencies of UAP, there may be information that the nurse knows or should have known to indicate UAP are not competent in a particular situation. Another example of improper delegation occurs when the nurse does not provide the required supervision for UAP. The nurse should always be available for questions or further instruction. Delegation can also occur laterally to another caregiver, as in the Eyoma case where the nurse improperly delegated the care of a patient in the post-anesthesia recovery room to another nurse (Eyoma v. Falco, 1991). Nurse Falco asked another nurse to watch her patient while she left the room but did not get a response from the other nurse. Thus, the other nurse did not acknowledge the delegation, and Nurse Falco was found liable for the patient injury resulting from improper delegation and patient abandonment.

Proper Delegation Without Nurse Liability

If the nurse has delegated properly, UAP can be individually liable for their actions. One example is when UAP do not inform the nurse of an inability to perform a task or when UAP perform a task incorrectly, even after instruction and supervision. UAP who perform tasks that are beyond those delegated or are outside their competencies are liable for their own actions and for mistakes or adverse patient outcomes as a result of their actions. The liability of UAP is generally shifted to the institution as the employer.

Staffing Issues

Inadequate staffing is not a rationale for delegating tasks. In such an instance, nurses need to document their refusal to delegate a task as based on concern for patient safety and its effect on patient care. This should be forwarded to a supervisor who has the power to correct the staffing. By taking these steps, the nurse is typically shifting the liability to the institution for any untoward outcomes resulting from the situation.

Many cases related to malpractice involve issues of nurses working with unlicensed personnel and whether the nurse provided proper instruction or supervision in the patient care situation. The cases do not often use the term delegation when referring to nurses working with UAP, but this is involved with most of the cases where the actions of both the nurse and the UAP are questioned. Cases are reported more frequently in nursing homes, long-term care settings, and homecare settings and often involve nurses' aides or home healthcare aides. The reality of utilizing increased numbers of UAP in the workplace in all settings is a trend that will likely continue.

Failure to Communicate and Report

In the case of Milazzo v. Olsten Home Health Care, Inc. and Kathleen Broussard, RN (1998), the plaintiff, Milazzo, had permanent injuries as a result of delay in treatment. Milazzo was a 2nd-day postop patient in the hospital recovering from placement of a shunt to relieve pressure in the ventricles surrounding her brain. Her family hired Buchanan as a “sitter” from the defendant agency to be with Milazzo over the night shift. Buchanan was also a certified nurses' aide and personal care attendant. Part of Buchanan's duties was to assist the patient Milazzo and report any significant changes in her condition. Nurse Broussard performed a neurological assessment at the beginning of the shift, according to the standard of care, and visited the patient, who was sleeping, about every 2 hours thereafter. At each of the patient visits, the nurse asked the sitter how the patient was doing, and the sitter always said, “fine.” Nurse Broussard told Buchanan to let her know if anything was wrong. However, at one point during the night, the sitter had called for the assistance of two unit nursing assistants to help her take the patient to the bathroom and then put her back to bed. At that time, the patient Milazzo was unable to stand and was “leaning to the left” and required this extra assistance. Earlier, Milazzo had ambulated with just Buchanan's help and walked to the bathroom. Buchanan claimed she thought the nursing assistants would tell the nurse about Milazzo's change in condition, but no one reported this to Nurse Broussard or to the patient's family. The sitter did write the change on the form at the end of her overnight shift and informed the patient's daughter, who had come to stay with her during the day. When examined by the physician that morning, Milazzo was unable to move her left side and was conversing inappropriately. Tests determined irreversible neurological damage and Milazzo required further cranial surgery. At trial, it was determined that Nurse Broussard had followed the standard of care but that the sitter Buchanan had been negligent in not reporting significant changes in the patient's condition. Earlier intervention would have resulted in a greater chance of recovery.

Even though the nurse was found not to be at fault for the patient's injuries, this case points to the need to clearly communicate with sitters and nursing assistants and to clarify reporting procedures.

Similarly, in Molden v. Mississippi (1998), two nurses' aides appealed the decision of the trial court in affirming the state department of health's finding of negligence and revocation of their nurse aide certifications. This decision was upheld by the Supreme Court of Mississippi. The court found that nurse aides Molden and Avery were negligent when a nursing home resident experienced second-degree burns after a whirlpool bath. Molden tested the water with her double-gloved hand, gave the bath, and was assisted by Avery. After the resident's bath, Avery stated she told Molden to report to the treatment nurse that the resident's skin was peeling and that her toe was bleeding. Neither Avery nor Molden reported the resident's symptoms, but Molden told Nurse Harrison that the resident was ready for the dressings for her decubitus ulcer. Nurse Harrison, a licensed practical nurse (LPN), discovered that the resident's legs were very red and had blisters on them, which she reported to the charge nurse. The resident was taken to a hospital and treated for second-degree burns. Thereafter, both Avery and Molden were reported to the health department, which, after a hearing, revoked their certifications and placed them permanently on the Nurse Aide Abuse Roster.

Again, although nurses were not found at fault in this case, and the conduct of the nurse aides cannot be excused, it may be that policies related to checking bath water temperature should be clarified and reviewed with the staff. Unlicensed staff members can greatly benefit from periodic review and education regarding delegated tasks to improve patient outcomes.

Failure to Supervise/Check Assignment of Unlicensed Staff

In Williams v. West Virginia Board of Examiners (2004), Nurse Williams appealed a decision of the nursing board to suspend her license for 1 year. Williams was employed as a nurse manager who supervised homemaker-health workers. As part of her duties, she was required to make periodic visits to the home when home health aides were present, review patient records, and update documentation of individuals' problems and progress that were recorded in patient in-home files. A state health department inspector found deficiencies in several of these areas. On one occasion there were progress notes documented for the nurse manager's patient visit when home health aides were present at the person's home at the same time, but the home health aides denied that Nurse Williams had visited. Nurse Williams could not produce handwritten notes for the required paperwork to document other scheduled visits. Several clients also denied that visits from the nurse occurred as she had reported. The nursing board found that Williams was guilty of violating standards of the profession when she falsely documented visits. They placed her on probation and suspended her license for a year, which was upheld on appeal. Part of the defense for her actions was that she had an overly large caseload, but the health inspector found the nurse-patient ratio to be consistent with standards.

In another case of supervising unlicensed health assistants, Nurse Hicks, an LPN, was disciplined for patient neglect when a resident was found tipped over in his wheelchair and had not been returned to bed by nursing home assistants (Hicks v. New York State Department of Health, 1991). Part of Nurse Hicks's duties was to ensure that nursing home residents were placed in bed and received appropriate care during her evening shift. Security personnel found the resident in the dark, half in his bed and half still restrained in his overturned wheelchair. There was evidence of urine and hardened feces dried on his skin when he was found, and this was documented in the nurse's record. The court upheld the health department's finding of patient neglect against Nurse Hicks. The case was grounded on her failure to properly supervise the nursing assistants and ensure that their duties had been completed. Although the court did not use the term delegated, the principle is the same where accountability remains with the licensed professional who assigns and supervises tasks to UAP.

Improper Delegation of Tasks

In Singleton v. AAA Home Health (2000), the physician orders specified that “skilled nurses” should pack the client's four decubitus ulcers and change the dressing. The defendant home healthcare agency (AAA) provided the caregivers. Nurses had performed the wound packing and dressing changes for over a year, but the wound worsened and the client needed additional surgery 2 years later to assist in wound healing. At that time, it was discovered there was old gauze in the wound that had not been removed. The wound continued to fail to heal, and a lawsuit commenced alleging that the failure to remove the old gauze caused delay in wound healing and further damage. At issue in the case was whether unlicensed “sitters” performed “wound care” and whether they were taught the packing procedure. There was documentation by the supervising nurse that she had instructed the sitters on how to pack the wound, but the sitters denied this, stating that they only changed the outer layer of the dressings. None of AAA's nurses had observed sitters perform this wound care procedure. The plaintiff's expert witness testified that the standard of care required documentation of the number of gauzes used to pack in the wound and the number removed from the wound for each dressing change. In finding that the defendant breached its duty to the plaintiff, the court granted the plaintiff's motion for a judgment notwithstanding the verdict (JNOV) in favor of the plaintiff. Part of the finding for liability was based on the duty of skilled nurses who worked for the agency to properly implement the physician's orders for skilled nurses to pack the wound.

This case presents many issues related to the inadequate wound care that the patient received, including that it was not a delegable task (ordered to be performed by skilled nurses), whether the procedure was taught properly, and whether the task (even if properly delegated) was properly supervised. Based on facts presented in the Singleton case, it appears that none of these conditions or steps for safe and effective delegation took place.

In Fairfax Nursing Home v. Department of Health and Human Services (2002), a nursing home received substantial fines by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) for placing residents needing ventilator assistance at great risk of harm. Inspectors found many violations of documentation, poor follow-up, and inadequate care of these residents, resulting in several deaths. The nursing home was found to have lacked substantial compliance with regulations required for proper care of residents requiring ventilator assistance and lacked policies and procedures to protect them. Many residents were found to have ventilator-associated pneumonia that was inadequately diagnosed and treated. This presented a “risk of immediate jeopardy” that justified the severe fines and requirements to comply with standards. Among the cited deficiencies was a state surveyor's observation of a Fairfax employee's failure to use sterile technique while performing tracheostomy care and neglect in hyperoxygenating the resident before and after suctioning the tracheostomy. In some instances, the suctioning procedure was performed by nurses' aides as unlicensed personnel. The overwhelming systemic nature of the problems in care of residents resulted in fines of more than $3,000 per day for 105 days by an administrative law judge, which was upheld on appeal.

Proper Delegation, Protocols, and Supervision

In Hunter v. Bossier Medical Center (1998), a hospital successfully defended a patient's medical malpractice action by presenting evidence that nurse aides and the registered nurse followed proper procedures and protocols. The patient Hunter was ambulated by two nurses' aides and then was standing near the wall in his room while his bed was being made by one of the aides. Hunter became lightheaded and was “eased to the floor” by the other nurses' aide. When Nurse Montano entered the room and checked the patient, she found Hunter leaning up against the nurses' aide's legs, which was consistent with a patient who had been slid to the floor. Hunter was found not to have immediate injuries from the incident. After discharge, he later had some pain and other problems that he attributed to his “fall” in the hospital. Hunter claimed that he had lost consciousness and woke up with his leg bent under him. However, the medical review panel (MRP) found the testimony of the nurses' aides (who had 20 years of experience between them) and Nurse Montano to be persuasive and placed importance on Nurse Montano's medical chart notation that documented the events at the time. The nurses' aides also referred to a training manual and identified the page for the procedure they learned for “easing” a patient who is falling to the ground. Thus, the appeals court affirmed the jury's finding in favor of the defendant hospital.

This case underscores the importance of proper procedures, documented training, and supervision of nurses' aides. Along with the factual and objective documentation of the nurse that supported the finding that the standard of care was met, the Hunter case illustrates that with these protections, safe and effective care for patients can occur when unlicensed personnel are utilized. Doing so will often determine whether the institution can successfully defend itself against malpractice claims.