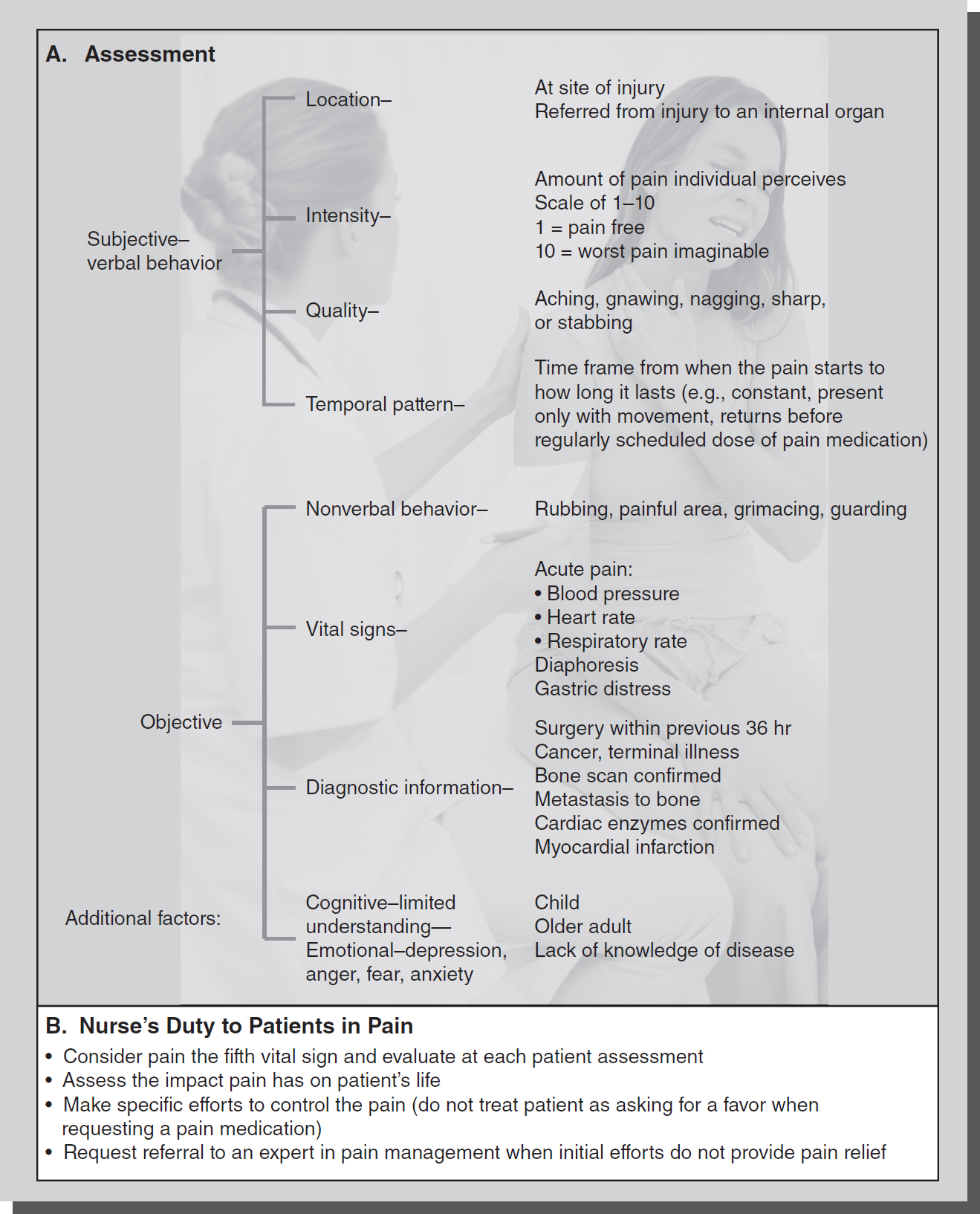

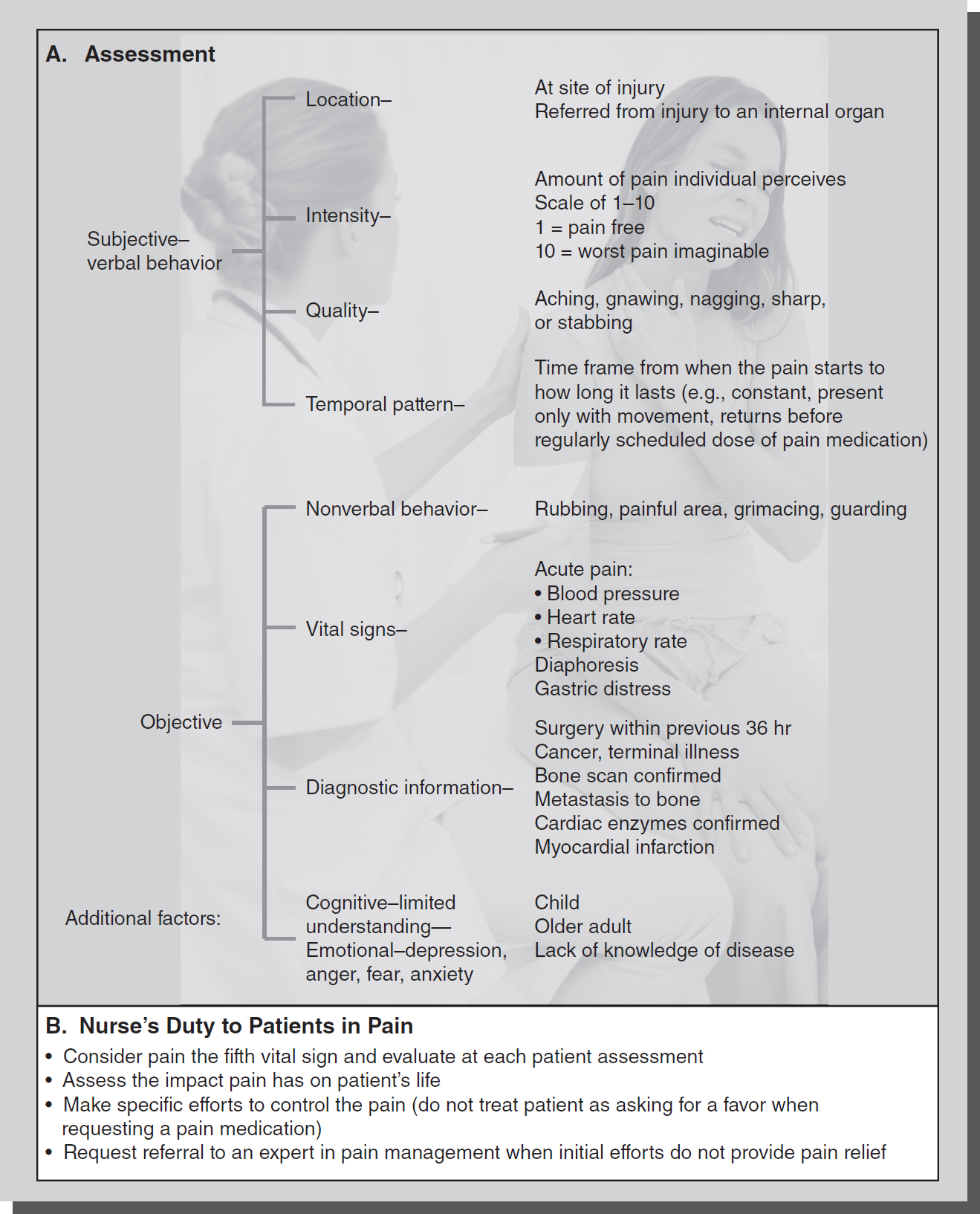

Figure 16-1 Nurse's role in pain control.

© Jones & Bartlett Learning; © Wavebreakmedia/Thinkstock (photo)

Nurses have a clear duty to relieve the pain and suffering of patients under their care. However, sometimes this duty is confounded by ethical dilemmas such as under- or over-treatment of pain, and the continuing effects of the opioid crisis and addiction. These factors have caused nurses and others to question the traditional methods of prescribing medications for pain control and the use of opioids in many situations. Pain control is currently viewed as being best relieved by multimodal options, including nonpharmacological means and complementary or alternative therapies (ANA, 2016). The effects of the opioid crisis have led to changes and regulation in the prescribing and use of opioids for pain relief. National debate on the appropriate use of opioids highlights the complexities of providing optimal management of pain. While effective in treating acute pain and some types of persistent pain, opioids carry significant risks. This results in tension between a nurse's duty to manage pain and the duty to avoid harm (Stokes, 2018).

The nurse's duty to provide appropriate pain management for patients is derived from several sources. Professional standards include the American Nurses Association (ANA, 2018) position statement. The ANA believes that:

- Nurses have an ethical responsibility to relieve pain and the suffering it causes.

- Nurses should provide individualized nursing interventions.

- The nursing process should guide the nurse's actions to improve pain management.

- Multimodal and interprofessional approaches are necessary to achieve pain relief.

- Pain management modalities should be informed by evidence.

- Nurses must advocate for policies to assure access to all effective modalities.

- Nurse leadership is necessary for society to appropriately address the opioid epidemic (ANA, 2018, p. 1).

There is also recognition by the ANA that nurses may experience moral distress in providing pain relief for patients. Nurses may experience moral distress when external constraints keep them from optimally managing their patients' pain. Nurses need to preserve their professional and personal integrity by developing the moral courage and resilience necessary to reduce moral distress when managing pain (ANA, 2018).

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), as the lead federal agency charged with improving the safety and quality of America's healthcare system (within the Department of Health and Human Services), has guidelines for both acute and chronic pain management and cancer pain management in various settings. Additionally, this organization has specific guidelines based on evidence related to the use of opioids for pain management (AHRQ). The American Academy of Pain Medicine (AAPM) is a multidisciplinary organization dedicated to research and advocacy for pain management. The organization specifies best practices and guidelines for treatment of various types and sources of pain, and promotes pain research and advocacy (AAPM). These authoritative resources would likely be cited by courts in establishing what would be the proper standard of care in these situations.

In 2001, The Joint Commission issued a standard that all patients have the right to have their pain assessed and treated. The organization offers current pain assessment and management standards on its website (The Joint Commission). Standards for hospitals include that the hospital must identify pain assessment and pain management, including safe opioid prescribing as an organizational priority; facilitate practitioner and pharmacist access to prescription drug monitoring program databases; and provide nonpharmacologic pain treatment modalities (The Joint Commission, 2017, 2018).

Additionally, some states have passed legislation in the form of statutes called “pain relief acts.” These acts generally specify that neither disciplinary nor state criminal prosecution shall be brought against healthcare providers for the therapeutic treatment of intractable pain.

Pain is one of the most compelling reasons why people seek medical care. Pain is a protective mechanism that alerts the person to potentially harmful stimuli.

There are three types of pain. Acute pain occurs immediately after an injury and continues until the healing is completed. If acute pain is not managed effectively, it can progress to a chronic state. Chronic pain lasts for a prolonged period of time, usually for more than 6 months, and is often associated with depression. Malignant pain can be described as intractable and is often associated with cancer or other prolonged and debilitating conditions.

A nurse is responsible for assessing subjective and objective data (see Figure 16-1A). A physical assessment, including a review of the patient's vital signs (temperature, pulse, respirations, and blood pressure) is essential. Pain assessment has been designated as the “fifth vital sign,” and is included when routine vital signs are assessed. The nurse should also assess the emotional response to pain and the results of diagnostic tests that confirm painful events, such as a bone scan that confirms metastasis of cancer to the bone.

The most common approach to pain management is the use of analgesic medication, although nonpharmacological interventions are also increasingly used and may accompany analgesic medications. The physician orders analgesics; however, the nurse is responsible for administering the drugs, evaluating their effectiveness, and notifying the physician if the relief of pain is inadequate. Most analgesics are given “around the clock,” or by patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), with other doses or medications given for breakthrough pain. In a hospital or acute care setting, the nurse:

- Assesses the patient's pain using an appropriate and validated pain assessment tool. (For adults, the numeric scale-from 1 as the lowest amount of pain to 10 as the highest-is most often used. For young children, the FACES scale or Neonatal Infant Pain Scale can be used.)

- Documents the specific location of pain-such as the upper, middle, or lower back region-and descriptive factors such as “stabbing,” “sharp,” or “pain with inhalation.”

- Considers, implements, and documents nonpharmacologic pain-relief interventions, such as guided imagery or distraction.

- Completes AIR cycles for pain management: A = assessment, I = intervention for pain relief, R = reassessment to determine if intervention has been effective (within 30 minutes of pain intervention).

- Documents AIR cycles and the pain scale used.

- May determine if and when an analgesic is given if the analgesic is ordered on an as-needed basis (prn).

- Selects the appropriate analgesic when more than one is prescribed.

- Knows the drug's action, potency, absorption, interactions with other medications, and pharmacokinetics.

- Evaluates the effectiveness of the medication, including trends in effective pain management.

- Observes for side effects or adverse reactions to analgesic, implements orders for medications used to treat these untoward effects (e.g., diphen-hydramine for allergic reaction).

- Informs and collaborates with the physician or prescriber and pain team when a change in medication is needed.

In the nonhospital setting, such as home care, the nurse is responsible for advising the person about analgesic use, but may implement some of the above steps depending on the situation. Pain management guidelines include a collaborative interdisciplinary team approach, an individualized pain management plan with patient and family input, an ongoing assessment, use of medication and nonmedication treatments, and institutionalized policies on pain management.

Postoperative pain is treated according to specific guidelines. Narcotics should be given around the clock immediately postop, as determined by the interdisciplinary team, not prn (or as needed). Analgesics should be given before or as soon as pain returns and before activity, such as ambulation or incentive spirometer use, to increase patient comfort and adherence to interventions.

Some people believe that administering large doses of morphine constitutes assisted suicide or euthanasia. It is the position of the ANA that relieving pain while providing palliative care, even if it hastens death in a person with a terminal illness, is the ethical and moral obligation of the professional nurse; it is not euthanasia or assisted suicide. The intent of the medication administration is the key question, and it remains to relieve the pain. This intervention must be consistent with the patient's wishes (ANA, 2016).

Nurses need to continually update and implement current standards of care. Agency policies need to be consistent with these so that the nurse's legal duty to provide pain relief for patients can be fulfilled. Documenting pain assessment as “generalized” or “severe” and describing pain relief as “good,” “better,” or “fair” is inadequate and fails to show that the standard of care was met. Holding back pain medication in the belief that the patient is addicted without proper assessment, evaluation, and medical diagnosis is considered “inhumane treatment” and leaves the nurse professionally liable. The nurse has a shared responsibility and independent duty to provide appropriate pain management for patients, and they must be part of the decision-making process (see Figure 16-1B).

The courts have set the precedent for healthcare provider duty (liability) to properly manage pain by best evidence guidelines. The sentinel case is a North Carolina court decision in 1991. Mr. James had terminal prostate cancer that metastasized to the spine and femur. He had 6 months to live. The long-term care nurse independently determined that Mr. James was addicted to morphine and used alternative pain management with no diagnosis, assessment, or orders from the primary physician, who had ordered pain relief every 3 hours. The family sued, and the court held that the treatment of Mr. James was “inhumane,” that the nurse and her employer had a duty to the patient to relieve his pain and not withhold the pain medication. The verdict awarding $15 million in damages sent a strong message to the healthcare community about the duty to relieve pain (Estate of Henry James v. Hillhaven Corp., 1991).

In State v. McAfee (1989), the issue before the court was the right of a patient with quadriplegia to refuse ventilator support. In holding that Mr. McAfee had the right to refuse lifesaving medical treatment, the court made clear that in discontinuing ventilatory support in a patient who was incapable of spontaneous respirations, he was entitled to sedative administration. The right to discontinue medical treatment was inseparable from his right to do so pain-free.

In United States v. Braddix (2021), a nurse practitioner (defendant Braddix) filed a motion to suppress evidence gathered in a criminal investigation of his controlled substances prescribing practices. In denying this motion, the district court found there was sufficient “probable cause” to conduct this search and that no violations had occurred. The court declined to hold an evidentiary hearing on the matter. Although the case has not been decided on its merits, the allegations made against Braddix and the physician he worked with are notable. Braddix was indicted on August 22, 2019, with “Conspiracy to Distribute Controlled Substances Prescribed Not for a Legitimate Medical Purpose and Not in the Usual Course of Professional Practice” in violation of federal drug statutes. Among the allegations are that he prescribed narcotics for patients (and undercover drug agents) without proper assessments, history taking, or tests, and offered extended refills in exchange for cash payments. Review of the Nevada Prescription Monitoring Program (PMP) data showed that defendant Braddix and Dr. Ridenour (a physician who worked with the defendant at a family practice clinic) both appeared to be over-prescribing a large amount of controlled substances, specifically hydrocodone, oxycodone, and other controlled substances to patients outside the usual course of professional practice and not for legitimate medical purposes. The PMP data also showed that Dr. Ridenour and Braddix prescribed each other excessive amounts of controlled substances on numerous occasions (Braddix, 2021). These allegations obviously involve serious criminal violations, and show the kinds of scrutiny that advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) prescribing controlled substances can be subject to. Any advanced practice nurses permitted to prescribe these substances are cautioned to follow standards of care for assessment, follow-up, and documentation of patients' need for these medications, and to follow all federal and state regulations for prescription of controlled substances.