Information ⬇

Figure 39-1 Requirements for source testing.

© Jones & Bartlett Learning

Nurses have a duty not to negligently expose patients to infectious diseases, including diseases from other patients or from the nurses themselves. Although there are state and federal statutes that protect the confidentiality of employees who have human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), nurses living with HIV must find the balance between maintaining their own confidentiality and not exposing others to HIV transmission while performing professional duties. Likewise, healthcare agencies have a duty not to negligently expose employees to HIV or other bloodborne pathogens in the performance of their duties and must have in place policies and procedures for exposure prevention and a robust postexposure procedure.

Even with improved standards and procedures for protection, transmission of hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), HIV, and other pathogens from patients to healthcare workers remains a significant occupational hazard. The risk of transmission of pathogens can occur with mucocutaneous transmission through a break in the skin or from mucous membrane exposure of the eyes, nose, or mouth. The greatest risk of exposure is by percutaneous transmission through any break in intact skin whether from sharps injury (needles, stylets, surgical blades) or other types of tissue trauma. The risk of seroconversion after percutaneous exposure to blood with HIV is low (0.3%) compared to the much higher rate with HBV (30%) (Delisio, 2012).

Americans with Disabilities Act ⬆ ⬇

Employees with an HIV diagnosis are protected from job discrimination under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). An employer may not fire employees solely because they are living with HIV. Employees may be excluded from their job positions if their HIV disease prevents the employee from competently performing the job functions. An employer may establish qualifications standards that exclude otherwise qualified individuals with disabilities, such as people with HIV, when there is a significant risk of substantial harm to the health and safety of others. To exclude the qualified individual, the employer must show that the significant risk poses a “direct threat” to safety and that this direct threat is not eliminated or minimized by a reasonable accommodation. The employer must use objective and medically sound reasoning to establish the risk to others. For example, because HIV is transmitted by exposure to HIV-positive blood and not by casual contact, the employer would need to show a work environment where potential blood exposure is legitimate. Examples could be nurses who work in the operating room or in labor and delivery where there may be more blood exposure.

Regulatory Controls ⬆ ⬇

In 2001, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) published and began to enforce a revised version of the bloodborne pathogens standard (BPS). Since then, the use of safety-engineered devices to prevent sharps injuries has risen significantly. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about 1 in 10 healthcare workers experience a needlestick injury each year, but underreporting continues to be around 40% (Handelman et al., 2012). Both employers and employees must be familiar with these standards and requirements.

The American Nurses Association (ANA) advocated for and was instrumental in passage of the federal Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act (NSPA) of 2001 that includes a requirement for employers to document and annually review the facility's exposure-control plan, as well as the evaluation and implementation of safer needle devices. The act also requires employers to involve frontline nonmanagerial employees (often nurses) in identifying and choosing safer devices, and cost cannot be the sole factor in the selection. The employer must maintain a confidential log of injuries from contaminated sharps that includes:

- Type and brand of devices

- Department in which the injury occurred

- Explanation of how the injury occurred

The act applies to any facility under OSHA where employees may be exposed to blood or other infectious materials. Other state and governmental regulations may require more detail in reporting to include the presence or absence of any engineered sharps injury-prevention feature on the device involved, and a unique identification number for the incident to protect worker identity. Some facilities do not follow recommended practices for sharps safety and continue to underreport needlestick injuries. All healthcare agencies are encouraged to foster a culture of safety in preventing exposures. Employees need to report any unsafe working conditions, such as lack of safety-engineered injection devices or inadequate personal protective equipment (PPE). OSHA can be contacted by employees if employers do not comply with standards.

Another source of exposure to bloodborne pathogens can occur with splashes to unprotected skin or the eyes from exposure to blood or bodily fluids of patients. Many pathogens, including HIV, hepatitis C virus (HCV), influenza, herpes B virus, plague, rabies, and Ebola, have been documented to be transmitted via eye exposures (American Nurse Today, 2018). According to Exposure Prevention Information Network (EPINet®) national surveillance data from 2012 to 2016, nurses experienced a disproportionate number of all splashes and splatters-about 50% compared to all other healthcare professionals. These occur in patient or exam rooms, and about 25% occur evenly distributed between emergency departments and operating rooms. A large percentage of these are to the nurse's face or eyes (American Nurse Today, 2018). It is recommended that eye protection be worn when working with any blood or body fluids of patients.

Tracking and Surveillance Systems ⬆ ⬇

Standardized tracking and surveillance programs have been developed to record the incidence of percutaneous injuries and other exposures to blood and bodily fluids. The Exposure Prevention Information Network (EPINet®) system has been in place since 1993 (International Safety Center, 2020). This system contributes data annually to an aggregate database coordinated by the International Healthcare Worker Safety Center at the University of Virginia. The center collects data from more than 1,500 EPINet® participating hospitals and provides support for new policies to improve healthcare worker safety in this area. Data from both the EPINet® Sharps Injury Surveillance coordinated by the International Safety Center and the Massachusetts Sharps Injury Surveillance System (MSISS) provide information to assess where we are today in the process. In 2018, the largest percentage of all sharps injuries by department occurred in the operating room (OR) (44.3% EPINet®, 35.1% MSISS). Within the OR, physicians experienced the greatest numbers of injuries (52.8% EPINet®, 58.0% MSISS). It is important to note that in the OR, a large proportion of injuries are sustained by workers other than the original user of the device (25.5% EPINet®, 24.6% MSISS), which includes nurses. The risk is further extended during device disposal. These injuries impact critical professional groups, including surgical technicians, environmental services, laundry, and sterile processing personnel.

According to the International Safety Center (2020), the United States has made significant progress in protecting healthcare workers from exposure to bloodborne pathogens. Other countries use the Bloodborne Pathogens Standard (BPS) and the subsequent Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act (NSPA) as models for their efforts to address components of occupational health and safety in healthcare facilities. The year 2020 marks the 20th anniversary of the Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act and its amendment to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Bloodborne Pathogens Standard (29 CFR 1910.1030) (OSHA, 2001). Areas covered by these regulations include sharps disposal practices, evaluation, and selection of devices with sharps injury prevention features and personal protective equipment (PPE), education and training, recordkeeping for sharps injuries, HBV vaccination, and post-exposure follow-up. Over the past 20 years, the standard has contributed to significantly reduce needlesticks, sharps injuries, and blood and body fluid exposures, as well as the resulting infections from bloodborne viruses. Medical device manufacturers, in the United States and other countries, have also played an important role in reducing sharps injury risks to U.S. healthcare workers by developing innovative technologies and controls in a broad range of product categories. However, there is still work to be done, and in its 2020 consensus statement and call to action, the International Safety Center found that “More than half of sharps injuries involve devices lacking SIP (sharps injury prevention) features leading to a significant opportunity to implement change and reduce injuries” International Safety Center, 2020, p. 6). The ANA is a contributor to this statement as part of the Sharps Injury Prevention Stakeholder group, in collaboration with the International Safety Center.

Occupational Exposure ⬆ ⬇

Healthcare facilities may be liable to healthcare providers and others within the facility when exposure to bloodborne pathogens occurs due to negligence. The viability of the case depends on the individual facts, the legal theory the case is brought under, and the state's laws. A plaintiff will have to prove either that actual exposure (e.g., a needle-stick with HIV-positive blood) to the infectious disease occurred or that the fear of having the disease because of the exposure is “reasonable.” Usually under tort law a plaintiff cannot sue for mental anguish unless it is associated with a physical injury, but some courts have ruled that the reasonable fear of acquiring a serious disease is a compensable injury, as in the case of one nurse who sued for negligent infliction of emotional distress after being exposed to a needlestick from a patient with AIDS. The nurse had her case dismissed for failure to show that her emotional distress was based on an actual exposure and was based on a reasonable response to the actual medically demonstrated risk of contracting the disease. The nurse was tested periodically and after 6 months had not contracted the virus. Medical testimony was admitted that if she were to test positive, there was a 95% chance of it happening in the first 6 months. Therefore, the court found that beyond the 6 months, any emotional distress was, as a matter of law, unreasonable (Ornstein v. NYC Health and Hospitals Corp., 2006).

To qualify for workers' compensation, individual state laws require employees to provide documentation on the circumstances of the work-related exposure. To rule out preexisting HIV disease, the employee will be required to have a confidential HIV test within a few days (usually less than 10) of the exposure.

A nurse who claimed emotional distress causing mental disability was entitled to a percentage of workers' compensation after a needlestick injury. The court heard testimony on both sides as to the feasibility of the nurse being diagnosed with HIV but held there was no evidence that she experienced impairment from emotional distress (Stout v. Johnson City Medical Ctr., 1995).

Nurses' Rights with a Bloodborne Pathogen Exposure ⬆ ⬇

Healthcare providers must follow strict statutory guidelines when obtaining a patient's informed consent for HIV testing. Even nurses who are exposed to a patient's blood products must receive the patient's informed consent before testing the patient. When the patient refuses to have an HIV test, healthcare providers who were exposed may seek a court order but must show that they had a bona fide exposure and that their rights to the information of HIV status from the known source outweighs the source's right to refuse.

The statutes vary in each state, but the following is a general example of the process (see Figure 39-1). The healthcare worker must have a “bona fide exposure” during an occupational duty. A bona fide exposure is generally defined as exposure to blood, visibly bloody fluid, or other potentially infectious material to a puncture wound that breaks skin, mucous membrane exposure (such as a splash to the eye), or prolonged exposure to skin (which may be cut or abraded). An incident report describing the incident and identifying witnesses must be completed. OSHA requires that the employer attempt to obtain voluntary consent to the HIV test, and a physician must seek to obtain the consent. Upon refusal, the healthcare provider who was exposed will need to submit to a baseline HIV test. An evaluation committee made up of impartial healthcare providers will review the incident. This group determines whether the statute's criteria have been met. The healthcare provider may need to seek a court order. The employer of the nurse who was exposed bears the cost of this process. When the test is done, the confidentiality statute must be followed. The test results may not be included in the patient's healthcare record unless the results relate directly to the current medical care. If the patient wishes to receive the test results, then HIV counseling must be offered, including the source's right to confidentiality and mandatory disclosure of the results to meet state infectious disease reporting requirements.

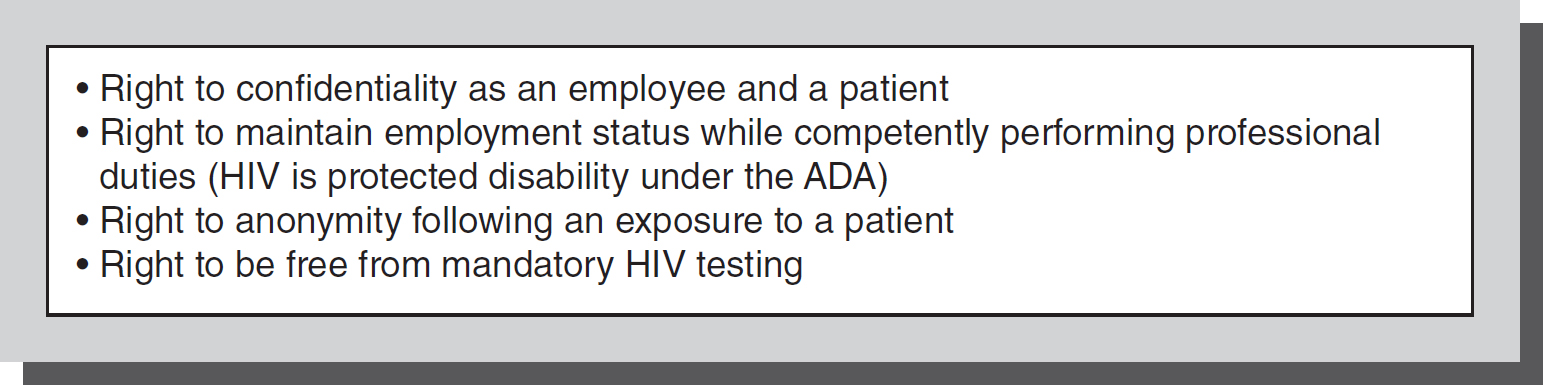

Nurses' Rights as Employees to Confidentiality ⬆ ⬇

The HIV confidentiality statutes that protect patients give healthcare providers the same rights (see Figure 39-2). A hospital has a duty to keep the results confidential under the HIV confidentiality statutes. The American Nurses Association (ANA) supports confidentiality regarding nurses living with HIV.

Figure 39-2 Rights of nurses living with HIV.

© Jones & Bartlett Learning

Nurses Living with HIV ⬆ ⬇

Healthcare providers are not required by law to reveal personal information on their health status, including their HIV status. In the absence of a legal duty, however, professional organizations, such as the ANA and the American Dental Association, have issued past position statements on the ethical obligation of disclosure. The ANA (1992) believes that nurses living with HIV may deliver safe and effective care without compromising the patient and should not be removed from patient care based on HIV status alone.

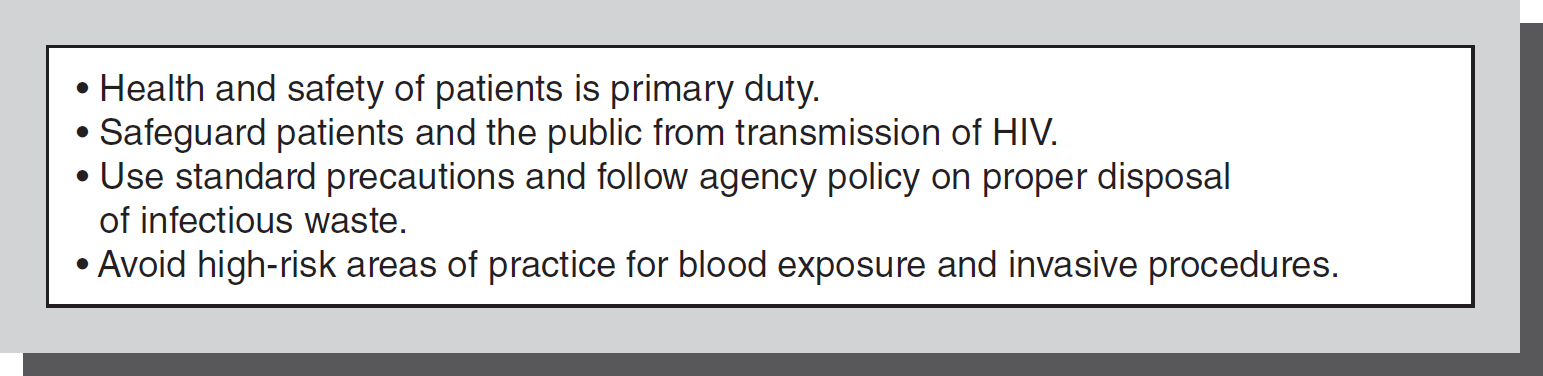

All nurses have a duty to protect their patients from harm. Therefore, nurses living with HIV should avoid exposure-prone invasive procedures. If an exposure to a patient does occur, the nurse with HIV has a duty to inform the patient of the exposure and potential risk for HIV transmission and diagnosis. This can be done while protecting the anonymity of the nurse. The nurse with HIV must understand the duty not to compromise patient care by remaining in a high-risk area of practice for blood exposure (see Figure 39-3). Standard precautions as recommended by the CDC must always be followed to minimize risk. Nurses with personal risk factors for HIV have an ethical obligation to know their own HIV status so steps can be taken to minimize risk to their patients.

Figure 39-3 Duty of nurses living with HIV.

© Jones & Bartlett Learning

The current ANA position statement on Care for HIV and Related Conditions (2019), emphasizes an approach to end the HIV epidemic, recognizing that nursing care is central to achieving HIV treatment and prevention goals. ANA's updated policies recognize a treatment-as-prevention approach, and further support access to postexposure (PEP) and preexposure (PrEP) treatment as a prevention strategy, as well as access to PEP when indicated for healthcare workers. ANA's updated policies support use of evidence-based approaches appropriate to key populations and encourage nursing practice and leadership that promotes culturally competent, nonstigmatizing care. ANA further recognizes a significant role for APRNs with prescriptive authority in HIV treatment and prevention, and has called for full practice authority at the federal and state levels to lead these efforts (ANA, 2019).

Agency HIV Policies ⬆ ⬇

The primary goal of HIV policies is to ensure the health and safety of all employees, patients, and visitors. Policies should reflect the most up-to-date medical and scientific information on the prevention of HIV transmission, postexposure management, and the implementation of infection control. Staff education and training should focus on infection control and on the privacy of people living with HIV, whether they be patients or employees. Staff members must have useful guidelines on postexposure protocols, such as HIV testing, for those who are involved in hazardous waste cleanup. Agency policy must be written to comply with the federal laws involving HIV, such as the ADA and the Rehabilitation Act, and state laws on workers' compensation and HIV informed consent/confidentiality.

References ⬆

- American Nurse Today. (2018). Practice matters: Part one in a series-Splash safety-Protecting your eyes. American Nurse Today, 13(3), 1-2.

- American Nurses Association. (1992). ANA position statement: HIV infected nurse, ethical obligations and disclosures (retired position statement). Washington, DC: Author.

- American Nurses Association. (2019). ANA position statement: Prevention and care for HIV and related conditions. Washington, D.C. Author

- Delisio , N. (2012). Bloodborne infection from sharps and mucocutaneous exposure: A continuing problem. American Nurse Today, 7(5), 34-38.

- Handelman , E., Perry , J. L., & Parker , G. (2012). Reducing sharps injuries in nonhospital settings. American Nurse Today, 7(9). https://www.myamericannurse.com/reducing-sharps-injuries-in-nonhospitalsettings/

- International Safety Center. (2020). Moving the sharps safety in healthcare agenda forward in the United States: 2020 consensus statement and call to action. 1-15. file:///D:/References%20for%20revised%20chapters%202021/hap%2039%20Sharps_Safety_In_Healthcare_Agenda_Forward_In_The_US%202020%20concensus.pdf

- Ornstein v. NYC Health and Hospitals Corp., 806 N.Y.S. 566; 2006 N.Y. App. Div. LEXIS 34 (N.Y. 2006).

- Stout v. Johnson City Medical Ctr., 1995 Tenn. LEXIS 601 (Tenn. 1995).

- The Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act, H.R. 5178, 106th Cong. (2001).