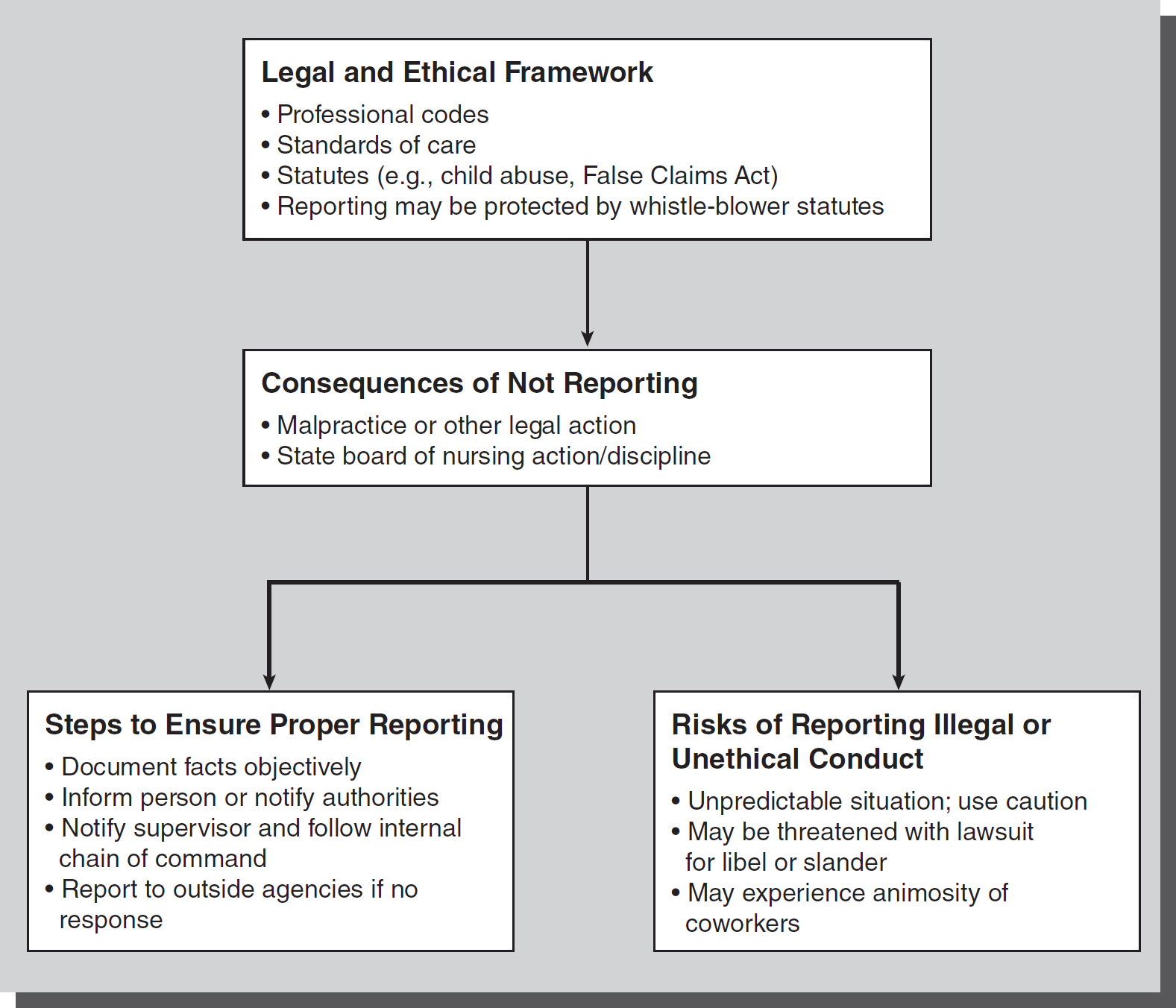

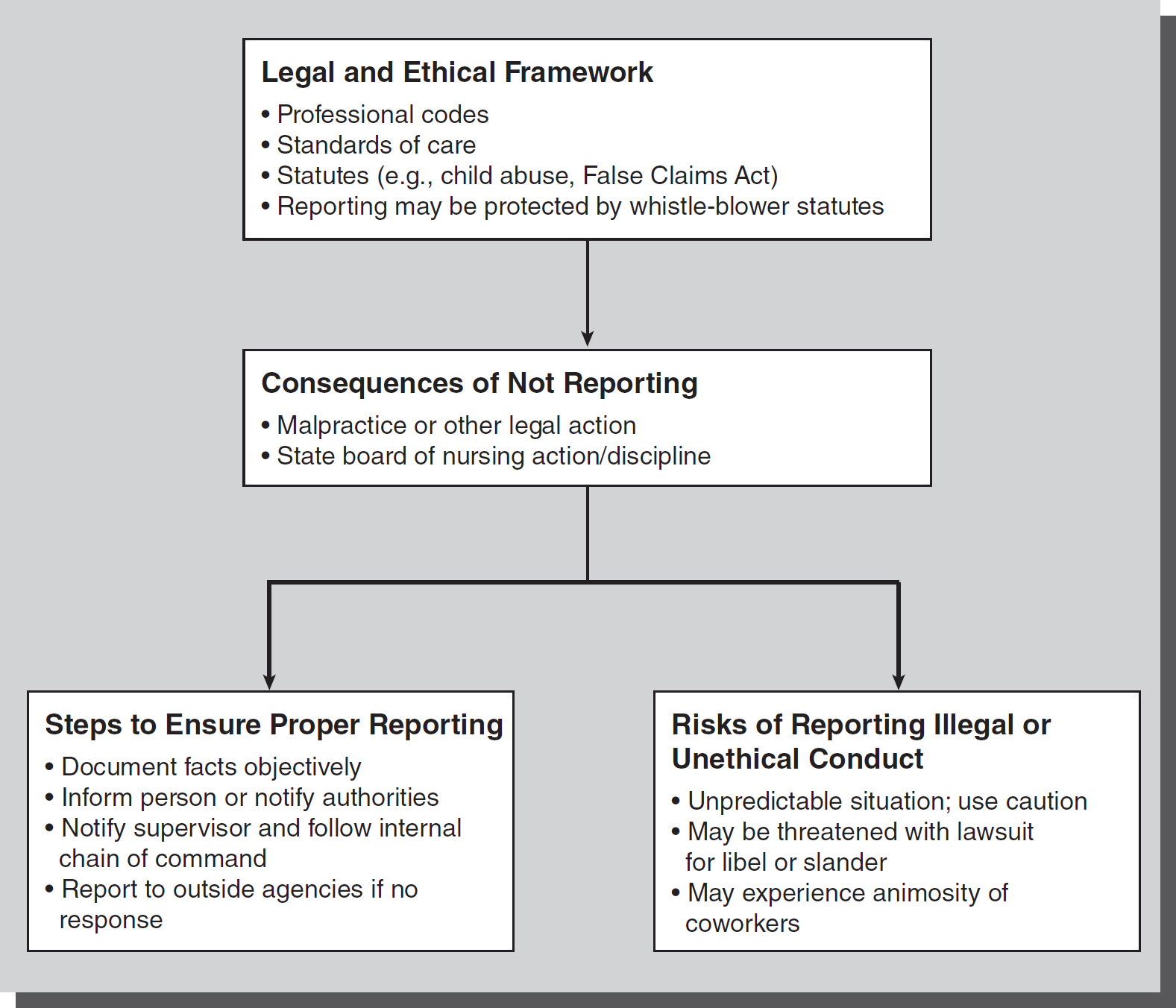

Figure 49-1 Sources, steps and risks of reporting.

© Jones & Bartlett Learning

The nurse is often in a position to recognize conduct of others that is potentially detrimental to the welfare of patients. In such situations, the nurse must seek a satisfactory solution for all parties involved but that ultimately protects the patient's health and safety. In seeking this solution, the nurse must not only weigh the risks and benefits of any action to be taken, but also the consequences of not taking any action. As in all situations, the nurse is responsible and accountable for such action or inaction (see

Figure 49-1).

Patient Abuse

A case involving hospital nurses who made a good faith report to protect an adult patient who was nonverbal and incapacitated from abuse resulted in the person accused of abuse filing a lawsuit against the hospital for defamation (Morganstern v. Mercy Hospital, 2007). In dismissing the plaintiff's complaint, the court noted that at least five nurses at the hospital stated they observed inappropriate physical conduct by Morganstern, the plaintiff and brother of the patient. In addition, there was documentation in the patient's medical record by at least three nurses that they had individually witnessed instances of inappropriate conduct by Morganstern on separate occasions. When this pattern was observed and documented, the nursing staff informed a social worker and ultimately the state Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Subsequently, hospital security issued a criminal trespass charge against Morganstern, notified the Portland, Maine, police department, and barred him from visiting his sister. Morganstern asserted that hospital staff defamed him through these actions because the staff did not like him, did not conduct an adequate investigation, and accused him in reckless disregard of the truth. However, the court found that nurses are mandatory reporters when “reasonable cause to suspect that an incapacitated or dependent adult . . . is at substantial risk of abuse, neglect, or exploitation” exists and that those making good faith reports were protected from civil liability. The evidence presented by testimony and affidavits of several nurses and their documentation in the medical record supported the claim of abuse and the report to the DHHS.

Whistle-blower Protection

Other statutes that impact reporting situations involving health and safety are whistle-blowing statutes. These federal or state statutes are designed to protect persons who “blow the whistle,” or report employers or others who can retaliate for such action. For example, an employee may be fired for reporting unsafe conditions or inaction of supervisors related to patient safety concerns. In some cases, a whistle-blowing statute could provide protection for the worker in seeking reinstatement after wrongful discharge, or it may prevent the worker from being fired. Some state nurses' associations are actively working to improve whistle-blowing protection for nurses who have been fired for complaining about chronic shortages of staff and other concerns related to patient safety.

The Texas Nurse Practice Act (NPA) and its whistle-blower sections that protect against retaliatory employment decisions taken because of an employee's report against a licensed healthcare practitioner was at issue in a case involving nurses who reported a licensed vocational nurse (LVN) to the board of nursing (Karen Clark, Lavern Worrell, and Jan Woodward v. Texas Home Health Inc., 1998). The three plaintiffs were serving on a peer review committee for their defendant employer, Home Health. The committee reviewed an LVN, Shaw, whose medical error resulted in a patient's death, and the plaintiffs informed Shaw that the incident must be reported to the Texas State Board of Vocational Nurse Examiners. They then waited for LVN Shaw's rebuttal and delayed making the actual report. At another meeting of the peer review committee, but before any rebuttal was received from Shaw within the 10-day deadline, the nurses told Home Health that they intended to report the incident. Home Health's chief executive officer, Sidney Dauphin, expressed concern over the potentially negative consequences if Shaw was reported. He allegedly told the nurses he would personally guarantee their salaries for 10 years if they lost their licenses for failing to report Shaw. At a third meeting, the nurses told Home Health they were reporting the incident without any further delay. Without adjourning the meeting, Dauphin immediately removed the nurses from the committee and relieved them of their administrative duties. The nurses then resigned and later sued Home Health, Dauphin, and others under the NPA for retaliatory employment action for reporting a healthcare practitioner, as prohibited by the Texas statute.

The trial court granted summary judgment for the defendants, but the Texas Court of Appeals reversed the decision, in part, and allowed a portion of the nurses' claim to go forward. The appeals court did not agree with the trial court that just because the actual report was not filed before the adverse employment decision (demotion), the statute did not provide protection for the nurses. The appeals court found that Home Health did have notice that the nurses were making the report to the board and could not hide behind the timing of the actual report when they made the retaliatory acts against these employees. The nurses were demoted after insisting they would report to the proper authorities, and the court found that this is the exact type of retaliatory conduct that the statute is in place to protect. Home Health claimed that it demoted the nurses because they insisted on reporting in their official capacities as administrators for Home Health instead of filing a report in their individual capacities. On the other hand, the nurses claimed that they told Home Health that it was critical to report the incident as soon as possible and that they intended to report despite Home Health's disapproval, even if it meant reporting as individuals. The court found Home Health's explanation for the demotion irrelevant because the statute expressly prohibits any adverse employment decision in response to “reporting.”

Additionally, Home Health filed a separate lawsuit against the nurses alleging libel and slander based on the nurses' report of Shaw, and the nurses then amended their complaint in this case to include a cause of action for damages and costs incurred as a result of participating in a “peer review.” The nurses were not allowed to collect these damages because peer review protection did not apply to review of LVNs. This case illustrates the dilemmas and risks associated with decisions when faced with conflicting expectations of employers and ethical and legal reporting requirements.

False Claims Act

A federal statute known as the False Claims Act (FCA) encourages uncovering fraud against the federal government and can be used in medical and agency billing fraud. A civil suit known as a qui tam lawsuit (where the government is substituted as the plaintiff and brings the lawsuit to protect the identity of the reporter) can be filed to recover lost money in the government's name. This statute provides whistle-blower protection to the one who makes the claim, and the person may be entitled to a portion of the recovery by the government. While it is sometimes difficult to obtain evidence in these cases, nurses have reported fraud under this statute.

For example, nurses were involved in a lawsuit involving the FCA that concerned billing procedures. The federal district court of Hawaii first ruled on a motion by the plaintiff physicians (and former employees of defendant medical center) to compel the defendants to produce certain billing and other records (United States of America ex rel. Kelly Woodruff, MD, and Robert Wilkinson et al. v. Hawaii Pacific Health et al., 2008a). In this qui tam lawsuit, plaintiffs alleged that the defendants violated the federal FCA, among other charges, by submitting false claims for procedures performed by nurses who were not licensed to perform them. The defendants allegedly submitted false UB-92 forms for the reimbursement of those charges and false cost reports based on these forms. According to the plaintiffs, codes on the forms implied that they were performed by physicians or licensed nurse practitioners with proper physician supervision. These involved procedures that were performed in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and also related to other pediatric hematology-oncology procedures. In the motion to compel discovery, plaintiffs sought an additional 255-plus UB-92 forms, access to original microfiche to copy or verify the integrity of the copies produced, electronic evidence related to the cost reports, billing and procedure policies, and documents pertaining to the identified nurses, including call schedules. Some of these records were sought for the years 1997 to 2001. As part of their request, the plaintiffs sought to compel the defendants to pay for a forensic analysis of their computer systems and files. According to the plaintiffs, the program that defendants used to print the protected document format forms that were produced to date is a claims editor program, which can change the content of the claim forms, and the program does not create an audit trail.

The court ruled that most of the documents must be produced by defendants at this stage in the litigation because relevancy, in terms of discovery, is a broad concept that is liberally construed under the Federal Rules of Procedure. The court further commented that discovery is designed to define and clarify the issues and is denied only if the information sought has no conceivable bearing on the case. Specifically related to the involved nurses' documentation, requests were also made for their collaborative practice agreements, personnel files for each of the identified nurses, and any personal logs or diaries any identified nurse created or maintained related to the procedures. In this instance, the court ruled that the defendant healthcare center had to produce the personnel files of the nurses but only information that indicated whether the nurses performed those procedures in question. The other requested documents related to the nurses did not need to be produced because there was no evidence that these documents were in the defendant's possession.

In a later stage of the lawsuit, the court granted the defendant's motion for summary judgment in the defendant's favor. The court found that the billing requirements for Medicaid reimbursement did not require that the procedures in question needed to be performed only by a physician or supervised nurse practitioners. The plaintiffs claimed that listing a physician's name in the billing fields implied that a physician had performed the procedures, and thus was the basis for the false claims for reimbursement to the government. The court also found that the defendant medical center did not consider the nurses to be advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), and that they did not need this recognition to act as nurse practitioners in their specialties in order to perform these procedures, as long as they were properly trained. However, the court did find that the nurse practitioners were properly licensed and recognized for advanced practice. In Hawaii, the APRN title is a “recognition” granted by the board of nursing, and not an actual license. The designation of APRN is based on the RN's educational attainment of a master's degree and certification from a national certifying body as recognized by the board. The nurse practitioners were pediatric nurse practitioners and neonatal nurse specialists who were properly certified and met the educational and other board requirements. The court specifically rejected any theory of FCA liability for defendants based on the allegations that the nurse practitioners were unlicensed and unsupervised (United States of America ex rel. Kelly Woodruff, MD, and Robert Wilkinson et al. v. Hawaii Pacific Health et al., 2008b).

This litigation underscores the need to have clear and specific documentation of who performed procedures, what their qualifications are, and whether advanced practice nurses or other practitioners are qualified to do them while meeting billing and compliance standards. Increasingly, recordkeeping is completed with computers and electronic information systems. One should keep in mind that these records are just as probative as hard-copy data and records, and the agency must be able to prove or defend the integrity of these systems.

In another lawsuit, Nurse Robbins sued her former employer alleging retaliatory discharge in violation of the FCA (Pamela Robbins v. Provena Hospitals, Inc., 2003). The defendant medical center's motion to dismiss was granted in part and denied in part. The plaintiff alleged that she was discharged because of her professional organization activities as chair of the Illinois Nurses Association (INA), the exclusive bargaining agent for the registered nurses at the medical center. In this capacity, she complained about the adequacy of staffing to the director of the Illinois Department of Public Health (IDPH), citing an inadequate number of staff members and its effect on patient care. The director advised the nurses to record any delays in patient treatment, and Robbins learned that this type of information could affect the medical center's right to participate in and receive reimbursement for Medicare- or Medicaid-related services. After the meeting, Robbins and other nurses changed the “assignment despite objection” (ADO) forms to expressly notify the medical center about delays in patient treatment as a result of inadequate staffing. Robbins also advised the nurses to file the forms with medical center supervisors to comply with Illinois regulatory law, which requires nurses to “report unsafe, unethical, or illegal care practice or conditions to the appropriate authorities.” The nurses at the medical center subsequently filed hundreds of ADOs from 2001 to 2002, which alleged delays in patient treatment and unsafe staffing levels.

Also in 2002, Robbins and other nurses helped organize public legislative hearings on Illinois House Bill 959, the Patient Safety Act, which proposed to give nurses a role in determining staffing levels and to impose penalties on facilities that refused to do so. Robbins and other nurses attended these televised hearings in March 2002. Before these hearings, Robbins alleges that she was detained and questioned by medical center security guards regarding the hearings. She further alleged that a manager confiscated a petition addressed to the IDPH. On May 22, 2002, several nurses were notified that their jobs had been eliminated. After meeting with human resources and while representing some of these nurses, medical center officials placed Robbins on indefinite suspension. She was terminated the next day for allegedly violating an agreement prohibiting nurses from engaging in strikes and work stoppages.

In terms of Robbins' claim that the activities were protected under the FCA, the court found that she did not meet the requisite criteria for such a claim. Specifically, while she did put her employer, the medial center, on notice that she was complaining to government authorities about the staffing levels, there was no notice that these actions were related to the employer's alleged false claims to the government. However, the court denied the defendant's motion for summary judgment related to two other counts related to retaliatory discharge, so those claims were allowed to go forward for the plaintiff Robbins.

This case illustrates the risks that professional activities, though seemingly valid and important for patient care, can have on one's career. The notion that one is “doing the right thing,” even through official channels, does not always protect against negative consequences of the activity. One has to weigh the risks and benefits in such situations and make personal decisions that will uphold one's personal beliefs and professional ethics and integrity.