Traumatic Hyphema

Symptoms

Pain, blurred vision, and history of blunt or penetrating trauma.

Signs

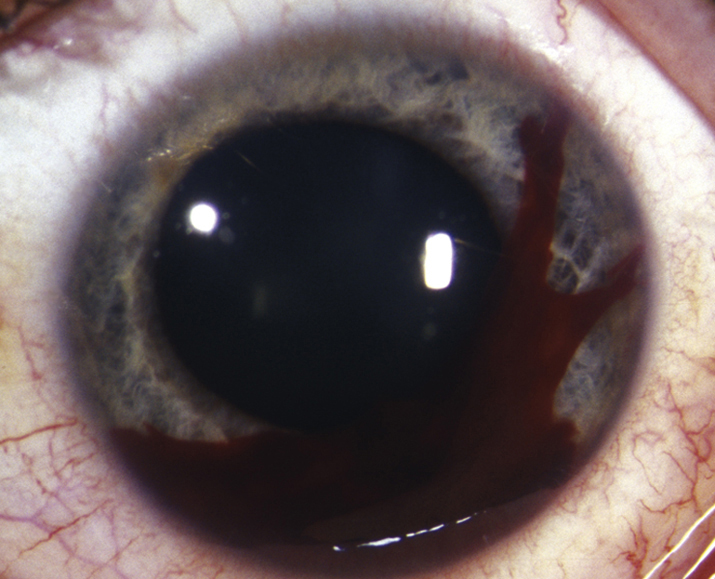

(See Figure 3.6.1.)

Clotted or unclotted blood in the AC, usually visible without a slit lamp. A total (100%) hyphema may be black or red. When black, it is called an “8-ball” or “blackball” hyphema, indicating deoxygenated blood; when red, the circulating blood cells may settle with time to become less than a 100% hyphema.

Workup

- History: Mechanism (including force, velocity, type, and direction) of injury? Protective eyewear? Time of injury? Recent intraocular surgery? Time and extent of visual loss? Maximal visual compromise usually occurs at the time of injury; decreasing vision over time suggests a rebleed or continued bleed (which may cause an IOP rise). Use of anticoagulant medications (e.g., aspirin, NSAIDs, warfarin, or clopidogrel)? Personal or family history of sickle cell disease or trait? Coagulopathy symptoms (e.g., bloody nose blowing, bleeding gums with tooth brushing, easy bruising, bloody stool)?

- Ocular examination: First rule out a ruptured globe (see 3.14, RUPTURED GLOBE AND PENETRATING OCULAR INJURY). Evaluate for other traumatic injuries. Document the extent (e.g., measure hyphema height) and location of any clot and blood. Measure the IOP. Perform a dilated retinal evaluation without scleral depression. Consider gentle B-scan ultrasound if the fundus view is poor. Avoid gonioscopy unless intractable increased IOP develops, but if necessary, perform gently. If the view is poor, consider UBM to better evaluate the anterior segment and look for possible lens capsule rupture, IOFB, or other anterior-segment abnormalities.

- Consider a CT scan of the orbits and brain (axial, coronal, and parasagittal views, 1-mm sections through the orbits) when indicated (e.g., suspected orbital fracture or IOFB, loss of consciousness).

- Patients should be screened for sickle cell trait or disease (order Sickledex screen; if necessary, may check hemoglobin electrophoresis) as clinically appropriate.

Treatment

Many aspects remain controversial, including whether hospitalization and absolute bed rest are necessary, but an atraumatic upright environment is essential. Consider hospitalization for noncompliant patients, patients with bleeding diathesis or blood dyscrasia, other severe ocular or orbital injuries, and/or concomitant significant IOP elevation and sickle cell trait or disease. Additionally, consider hospitalization and aggressive treatment for children, especially those at risk for amblyopia (e.g., those younger than 7 to 10 years), when a thorough clinical examination is difficult, or when child abuse is suspected.

- Confine either to bed rest with bathroom privileges or to limited activity. Elevate the head of the bed to allow blood to settle. Discourage strenuous activity, bending, or heavy lifting.

- Place a rigid shield (metal or clear plastic) over the involved eye at all times. Do not patch because this prevents recognition of sudden visual change in the event of a rebleed.

- Cycloplege the affected eye (e.g., cyclopentolate 1% or 2% b.i.d. to t.i.d., homatropine 5% b.i.d. to t.i.d., or atropine 1% daily to b.i.d.).

- Avoid antiplatelet/anticoagulant medications (i.e., aspirin-containing products and NSAIDs) unless otherwise medically necessary. Do not abruptly stop daily aspirin regimen without consulting with prescribing physicians.

- Mild analgesics only (e.g., acetaminophen). Avoid sedatives.

- Use topical steroids (e.g., prednisolone acetate 1% q.i.d. to q1h) if any suggestion of iritis (e.g., photophobia, deep ache, ciliary flush), evidence of lens capsule rupture, any protein (e.g., fibrin), or definitive WBCs in AC. Taper steroids quickly as soon as signs and symptoms resolve to reduce the likelihood of steroid-induced glaucoma.

- For increased IOP:

- Non–sickle cell disease or trait (≥30 mm Hg):

- Start with a beta-blocker (e.g., timolol or levobunolol 0.5% b.i.d.).

- If IOP is still high, add topical alpha-agonist (e.g., apraclonidine 0.5% or brimonidine 0.1% or 0.2% t.i.d.) or topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitor (e.g., dorzolamide 2% or brinzolamide 1% t.i.d.). Avoid prostaglandin analogues and miotics (may increase inflammation). In children younger than 2 years, topical alpha-agonists are contraindicated.

- If topical therapy fails, add acetazolamide (up to 500 mg p.o. q12h for adults, 20 mg/kg/d divided three times per day for children) or mannitol (1 to 2 g/kg i.v. over 45 minutes q24h). If mannitol is necessary to control the IOP, surgical evacuation may be imminent.

- Sickle cell disease or trait (≥24 mm Hg):

- Start with a beta-blocker (e.g., timolol or levobunolol 0.5% b.i.d.).

- All other agents must be used with extreme caution: Topical dorzolamide and brinzolamide may reduce aqueous pH and induce increased sickling; topical alpha-agonists (e.g., brimonidine or apraclonidine) may affect iris vasculature; miotics and prostaglandins may promote inflammation.

- If possible, avoid systemic diuretics because they promote sickling by inducing systemic acidosis and volume contraction. If a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor is necessary, use methazolamide (50 or 100 mg p.o. b.i.d. to t.i.d.) instead of acetazolamide (controversial). If mannitol is necessary to control the IOP, surgical evacuation may be imminent.

- AC paracentesis may be considered if IOP cannot be safely lowered medically (see APPENDIX 13, ANTERIOR CHAMBER PARACENTESIS). This procedure is typically a temporizing measure when the need for urgent surgical evacuation is anticipated.

- Non–sickle cell disease or trait (≥30 mm Hg):

- If hospitalized, use antiemetics p.r.n. for severe nausea or vomiting (e.g., ondansetron 4 or 8 mg q4–8h p.r.n.; if <12 years of age, please refer to the appropriate dosing instructions). Indications for surgical evacuation of hyphema:

- Corneal stromal blood staining, especially in children.

- Significant visual deterioration.

- Hyphema that does not decrease to ≤50% by 8 days (to prevent peripheral anterior synechiae).

- IOP ≥60 mm Hg for ≥48 hours, despite maximal medical therapy (to prevent optic atrophy).

- IOP ≥25 mm Hg with total hyphema for ≥5 days (to prevent corneal stromal blood staining).

- IOP ≥24 mm Hg for ≥24 hours (or any transient increase in IOP ≥30 mm Hg) in sickle cell trait or disease patients.

- Consider early surgical intervention for children at risk for amblyopia.

No definitive evidence exists regarding steroid use in improving outcomes for hyphemas. Use must be balanced with the risks of topical steroids (increased infection potential, increased IOP, cataract). In children, particular caution must be used regarding topical steroids. Children may get rapid rises in IOP, and with prolonged use, there is a risk for cataract. As outlined above, in certain cases, steroids may be beneficial, but steroids should be prescribed in an individualized manner. Children must be monitored closely for increased IOP and should be tapered off steroids as soon as possible. |

Increased IOP, especially soon after trauma, may be transient, secondary to acute mechanical plugging of the trabecular meshwork. Elevating the patient’s head may decrease IOP by causing RBCs to settle inferiorly and clot. |

Previously, systemic aminocaproic acid was used in hospitalized patients to stabilize the clot and to prevent rebleeding. This therapy is rarely used nowadays. Evidence supporting the use of topical antifibrinolytic agents such as aminocaproic acid and tranexamic acid is inconclusive. Some studies suggest that topical antifibrinolytic agents may be useful in reducing the risk of rebleeding but might prolong resolution time. Additionally, aminocaproic acid has been reported to have several adverse side effects; the benefits and risks of antifibrinolytic therapy remain controversial. |

Follow Up

- The patient should be seen daily after initial trauma to check visual acuity, IOP, and for a slit lamp examination. Look for new bleeding (most commonly occurs within the first 5 to 10 days), increased IOP, corneal blood staining, and other intraocular injuries as the blood clears (e.g., iridodialysis; subluxated or dislocated lens, or cataract). Hemolysis, which may appear as bright red fluid, should be distinguished from a rebleed, which forms a new, bright red clot. Rebleeding occurs in 0.4% to 35% of patients, usually 2 to 7 days after trauma. If the IOP is increased, treat as described earlier. Time between visits may be increased once consistent improvement in clinical examination is documented.

- The patient should be instructed to return immediately if a sudden increase in pain or decrease in vision is noted (which may be symptoms of a rebleed or increased IOP).

- If a significant rebleed or an intractable IOP increase occurs, hospitalization or surgical evacuation of the blood may be considered.

- After the initial close follow-up period, the patient may be maintained on a long-acting cycloplegic agent (e.g., atropine 1% daily to b.i.d.) depending on the severity of the condition. Topical steroids may be tapered as the blood, fibrin, and WBCs resolve.

- Protective glasses or an eye shield should be worn during the day and an eye shield at night.

- The patient must refrain from strenuous physical activities (including Valsalva maneuvers) for at least 1 week after the initial injury or rebleed. Normal activities may be resumed once the hyphema has resolved and the patient is out of the rebleed time frame.

- Future outpatient follow up:

- If hospitalized, see 2 to 3 days after discharge. If not hospitalized, see several days to 1 week after initial daily follow-up period, depending on condition severity (amount of blood, potential for IOP increase, other ocular or orbital injuries).

- Follow up 4 weeks after trauma for gonioscopy and dilated fundus examination with scleral depression for all patients.

- Some experts suggest annual follow up because of the potential for development of angle-recession glaucoma.

- If any complications arise, more frequent follow up is required.

- If filtering surgery was performed, follow up and activity restrictions are based on the surgeon’s specific recommendations.

Traumatic Microhyphema

Symptoms

See HYPHEMA above.

Signs

Suspended RBCs in the AC (no settled blood or clot), visible with a slit lamp. Sometimes there may be enough suspended RBCs to see a haziness of the AC (e.g., poor visualization of iris details) without a slit lamp; in these cases, the RBCs may eventually settle out as a frank hyphema.

Workup

See HYPHEMA above.

Treatment

- Most microhyphemas can be treated on an outpatient basis.

- See treatment for HYPHEMA above.

Follow Up

- The patient should return on the third day after the initial trauma and again at 1 week. If the IOP is >25 mm Hg at presentation, the patient should be followed daily for 3 consecutive days for pressure monitoring and again at 1 week. Sickle cell patients with initial IOP of ≥24 mm Hg should also be followed daily for 3 consecutive days.

- Otherwise, see follow up for HYPHEMA above.

Nontraumatic (Spontaneous) and Postsurgical Hyphema or Microhyphema

Symptoms

May present with decreased vision or with transient visual loss (intermittent bleeding may cloud vision temporarily).

Etiology of Spontaneous Hyphema or Microhyphema

- Occult trauma: must be excluded; evaluate for child or elder abuse.

- Neovascularization of the iris or angle (e.g., from diabetes, old central retinal vascular occlusion, ocular ischemic syndrome, chronic uveitis).

- Blood dyscrasias and coagulopathies.

- Iris–intraocular lens chafing.

- Herpetic keratouveitis.

- Use of anticoagulants (e.g., ethanol, aspirin, warfarin).

- Other (e.g., Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis, iris microaneurysm, leukemia, iris or ciliary body melanoma, retinoblastoma, juvenile xanthogranuloma).

Workup

As for traumatic hyphemas, plus:

- Gentle gonioscopy initially to evaluate for neovascularization or masses in the angle.

- Consider the following studies:

- Prothrombin time (PT)/international normalized ratio (INR), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), complete blood count (CBC) with platelet count, bleeding time, and proteins C and S.

- UBM to evaluate for possible malpositioning of intraocular lens haptics, ciliary body masses, or other anterior-segment pathology.

- Fluorescein angiogram of iris.

Treatment

Cycloplegia (see HYPHEMA), limited activity, elevation of head of bed, and avoidance of medically unnecessary antiplatelet/anticoagulant medications (e.g., aspirin and NSAIDs). Recommend protective rigid metal or plastic shield if etiology is unclear. Monitor IOP. Postsurgical hyphemas and microhyphemas are usually self-limited and often require observation only, with close attention to IOP.