Symptoms

Pain with eye movement; local tenderness; eyelid edema; binocular diplopia; crepitus (particularly after nose blowing); and numbness of the cheek, upper lip, and/or teeth. Tearing may be a symptom of nasolacrimal duct obstruction or injury seen with medial buttress, Le Fort II, or nasoethmoidal complex fractures, but this is typically a late complaint. Acute tearing is usually due to ocular irritation (e.g., chemosis, corneal abrasion, iritis).

Signs

Critical

Restricted eye movement (especially in upward gaze, lateral gaze, or both), subcutaneous or conjunctival emphysema, hypesthesia in the distribution of the infraorbital nerve (ipsilateral cheek and upper lip), point tenderness, enophthalmos (may initially be masked by orbital edema and hemorrhage), and hypoglobus.

Other

Epistaxis, eyelid edema, and ecchymosis. Superior rim and orbital roof fractures may manifest hypesthesia in the distribution of the supratrochlear or supraorbital nerve (ipsilateral forehead), ptosis, and step-off deformity along the anterior table of the frontal sinuses (superior orbital rim and glabella). Trismus, malar flattening, and a palpable step-off deformity of the inferior orbital rim are characteristic of tripod (zygomatic complex) fractures. Optic neuropathy may be present secondary to posterior indirect traumatic optic neuropathy (PI-TON) or from a direct mechanism (orbital compartment syndrome [OCS] secondary to retrobulbar hemorrhage, foreign body, etc.; see below).

Differential Diagnosis of Muscle Entrapment in Orbital Fracture

- Orbital edema and hemorrhage with or without a blowout fracture: May have limitation of ocular movement, periorbital swelling, and ecchymosis, but these will markedly improve or completely resolve over 7 to 10 days.

- Cranial nerve palsy: Limitation of ocular movement, but no restriction on forced duction testing. Will have abnormal results on active force generation testing. In cases of suspected traumatic cranial neuropathy, significant skull base and intracranial injury have occurred and CT imaging should be obtained.

- Laceration or direct contusion of EOMs: Often the site of penetrating injury is missed, especially if it occurs in the conjunctival cul-de-sacs. Look carefully for evidence of conjunctival laceration or orbital fat prolapse. Complete EOM laceration usually results in a large angle ocular deviation away from the injured muscle with no ocular movement toward the muscle. CT is often helpful in distinguishing EOM contusion from EOM laceration. On occasion, exploration of the EOM may be necessary under anesthesia.

Workup

- Complete ophthalmic examination, including visual acuity, motility, IOP, and globe displacement. Check pupils and color vision to rule out TON (see 3.11, TRAUMATIC OPTIC NEUROPATHY). Compare sensation of the affected cheek with that on the contralateral side; palpate the eyelids for crepitus (subcutaneous emphysema); palpate the orbital rim for step-off deformities. Evaluate the globe carefully for an apparent or occult rupture, hyphema or microhyphema, traumatic iritis, and retinal or choroidal damage. A full, dilated examination may be difficult in uncooperative patients with periocular edema but is extremely important in the management of orbital fractures. If eyelid and periocular edema limit the view, special techniques may be necessary (e.g., use of Desmarres eyelid retractors or clean bent paperclips [see Figure 3.9.1], lateral cantholysis, examination under general anesthesia).

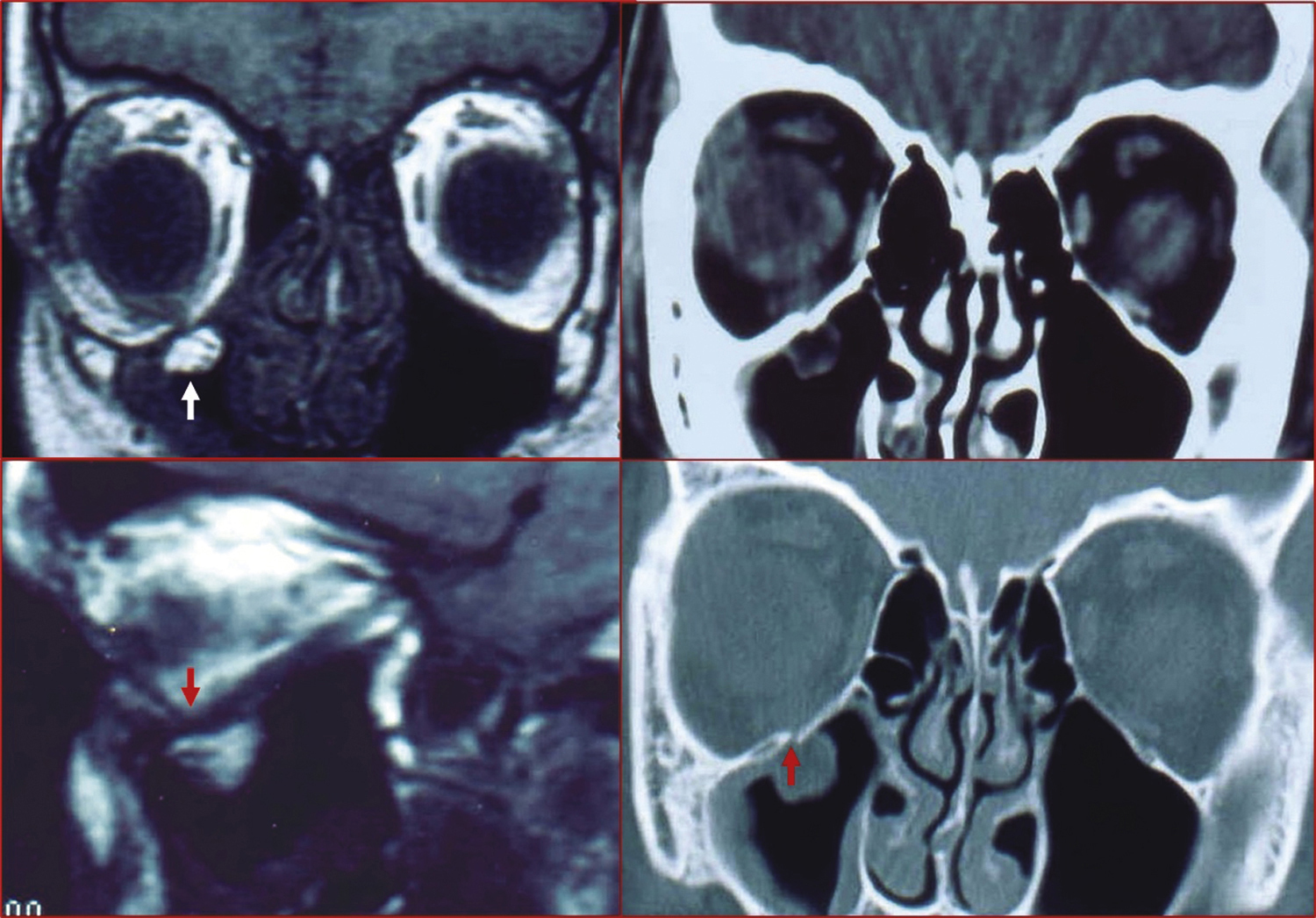

- CT of the orbit and midface (axial, coronal, and parasagittal views, 1- to 1.5-mm sections, without contrast) is obtained in all cases of suspected orbital fractures. Bone windows are especially helpful in fracture evaluation (see Figures 3.9.2 and 3.9.3), including the narrow, oft-missed WEBOF. Inclusion of the midfacial skeleton is mandatory to rule out zygomatic complex or other midfacial fractures. If there is any history of loss of consciousness, brain imaging is recommended.

3-9.3 Coronal and sagittal cuts of a white-eyed blowout fracture (WEBOF) in a patient with an entrapped inferior rectus.

White arrow, entrapped orbital soft tissue; red arrows, orbital floor fracture.

It is of paramount importance to rule out intraocular and optic nerve injury as quickly as possible in ALL patients presenting with suspected orbital fracture. |

Pediatric patients are particularly at risk for a unique type of blowout injury: the “trapdoor” fracture. Because pediatric bones lack complete calcification, they tend to “greenstick” rather than completely fracture. This results in an initial fracture, herniation of orbital soft tissue (including EOM) through the fracture site, and rapid snapping back of the malleable bone akin to a trapdoor on a spring. Because of the tight reapposition of the fracture edges, the soft tissue trapped within the fracture becomes ischemic. Children with this type of fracture often have a remarkably benign external periocular appearance but significant EOM restriction (usually vertical) on examination; this constellation of findings has been dubbed the “white-eyed blowout fracture” (WEBOF). Children may present with a vague history, allow only a limited ocular examination, and be misdiagnosed as having an intracranial injury (e.g., concussion) leading to delay in management of WEBOF. Be aware of the oculocardiac reflex (nausea or vomiting, bradycardia, syncope, dehydration) that can accompany entrapment. Even in cases where correct orbital imaging is performed, CT evidence of an orbital fracture may be minimal and routinely missed. Careful examination of coronal and parasagittal views is critical in such cases. In typical (i.e., non-WEBOF) orbital fractures, forced duction testing or testing of the doll’s eye reflex may be performed if limitation of eye movement persists beyond 1 week and restriction is suspected. In the early phase, it is often difficult to distinguish soft tissue edema or contusion from soft tissue entrapment in the fracture. SEE APPENDIX 6, FORCED DUCTION TEST AND ACTIVE FORCE GENERATION TEST. |

In the absence of visual symptoms (subjective change in vision, diplopia, periocular pain, photophobia, floaters or flashes), patients with orbital fractures are unlikely to have an ophthalmic condition requiring intervention within 24 hours. However, all patients with orbital fractures should undergo a complete ophthalmic examination within 48 hours of injury. Any patient complaining of blurred vision, severe pain, or other significant visual symptoms should undergo more urgent ophthalmic evaluation. |

Treatment

- Consider broad-spectrum oral antibiotics (e.g., amoxicillin/clavulanate [500/125 mg p.o. b.i.d. to t.i.d. or 875/125 mg p.o. b.i.d.], doxycycline [100 mg p.o. daily to b.i.d.], trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole [80/400 mg or 160/800 mg p.o. daily to b.i.d.], or cephalexin [250 to 500 mg p.o. q.i.d.] [adults]) for 7 to 10 days. Antibiotics may be considered if the patient has a history of chronic sinusitis or diabetes or is otherwise immunocompromised. This recommendation is based on limited, anecdotal evidence. In all other patients, the decision about antibiotic use is left to the treating physician. Prophylactic antibiotics should not be considered mandatory in patients with orbital fractures.

- Instruct the patient to avoid nose blowing. Forced air into the orbit can lead to OCS and optic neuropathy.

- Nasal decongestants (e.g., oxymetazoline nasal spray b.i.d.) for 3 days. Use is limited to 3 days to minimize rebound nasal congestion.

- Apply ice packs to the eyelids for 20 minutes every 1 to 2 hours for the first 24 to 48 hours and attempt a 30-degree inclination when at rest.

- Consider oral corticosteroids (e.g., methylprednisolone dose pack) if extensive swelling limits examination of ocular motility and globe position. Some experts advise the use of oral antibiotics if corticosteroid therapy is considered, but there are no data to support the effectiveness of such a regimen. Avoid corticosteroids in patients with concomitant traumatic brain injury (TBI).

- Neurosurgical consultation is recommended for all fractures involving the orbital roof, frontal sinus, or cribriform plate and for all fractures associated with intracranial hemorrhage. Otolaryngology or oral maxillofacial surgery consultation may be useful for frontal sinus, midfacial, and mandibular fractures.

- Consider surgical repair based on the following criteria.

Orbital fracture repair should be deferred or delayed if there is any evidence of full-thickness globe injury or penetrating trauma. Presence of hyphema or microhyphema typically delays orbital fracture repair for 10 to 14 days. |

Immediate Repair (Within 24 to 48 hours)

If there is clinical evidence of muscle entrapment with nonresolving bradycardia, heart block, nausea, vomiting, or syncope (most often encountered in children with WEBOF). Patients with muscle entrapment require urgent orbital exploration to release any incarcerated muscle to decrease the chance of permanent restrictive strabismus from muscle ischemia and fibrosis, as well as to alleviate systemic symptoms from the oculocardiac reflex.

Repair in 1 to 2 Weeks

- Persistent, symptomatic diplopia in primary or downgaze that has not improved over 1 to 2 weeks. CT may show muscle distortion or herniation around fractures. Forced ductions may be useful in identifying bony restriction. Note that diplopia may take more than two weeks to improve or resolve. Some surgeons will wait 6 to 8 weeks before offering surgical repair for persistent diplopia.

- Large orbital floor fractures (>50%) or large combined medial wall and orbital floor fractures that are likely to cause cosmetically unacceptable globe dystopia (enophthalmos and/or hypoglobus) over time. Globe dystopia at initial presentation is indicative of a large fracture. It is also reasonable to wait several months to see if enophthalmos develops before offering repair. There is no clear evidence that early repair is more effective in preventing or reversing globe malposition compared to delayed repair. However, many surgeons prefer early repair simply because dissection planes and abnormal (fractured) bony anatomy are more easily discernable before posttraumatic fibrosis sets in. It may be prudent to avoid early surgery for prevention of possible globe malposition in older patients, patients with significant medical comorbidities, or patients on anticoagulation therapy for significant cardiovascular conditions.

- Complex trauma involving the orbital rim or displacement of the lateral wall and/or the zygomatic arch. Complex fractures of the midface (zygomatic complex, Le Fort II) or skull base (Le Fort III). Nasoethmoidal complex fractures. Superior or superomedial orbital rim fractures involving the frontal sinuses.

Delayed Repair

- Old fractures that have resulted in enophthalmos or hypoglobus can be repaired at any later date.

The role of anticoagulation in postoperative or posttrauma patients is debatable. Anecdotal reports have described orbital hemorrhage in patients with orbital and midfacial fractures who were anticoagulated for prophylaxis against deep vein thrombosis (DVT). On the other hand, multiple large studies have also demonstrated an increased risk of DVT and pulmonary embolism (PE) in postoperative patients who are obtunded or cannot ambulate. At the very least, all inpatients with orbital fractures awaiting surgery and all postoperative orbital fracture patients should be placed on intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) therapy and encouraged to ambulate. In patients at high risk for DVT, including those who are obtunded from concomitant intracranial injury, a detailed discussion with the primary care team regarding anticoagulation should be documented, and the risks for and against such therapy should be discussed in detail with the patient and family. |

Follow Up

Patients should be seen at 1 and 2 weeks after trauma to be evaluated for persistent diplopia and/or enophthalmos after the acute orbital edema has resolved. If sinusitis symptoms develop or were present prior to the injury, the patient should be seen within a few days of the injury. Patients should also be monitored for development of associated ocular injuries as indicated (e.g., orbital cellulitis, angle-recession glaucoma, retinal detachment). Gonioscopy and dilated fundus examination with scleral depression is performed about 4 weeks after trauma if a hyphema or microhyphema was present. Warning symptoms of retinal detachment and orbital cellulitis are explained to the patient.