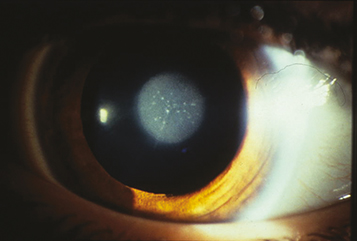

(See Figure 8.12.1.)

A white fundus reflex (leukocoria), absent or asymmetric red pupillary reflex, abnormal eye movements (nystagmus) in one or both eyes, and strabismus. Often appears asymptomatic in infants, delaying diagnosis. Infants with bilateral cataracts may be noted to be visually inattentive. In patients with a monocular cataract, the involved eye may be smaller. A cataract alone does not cause a relative afferent pupillary defect.