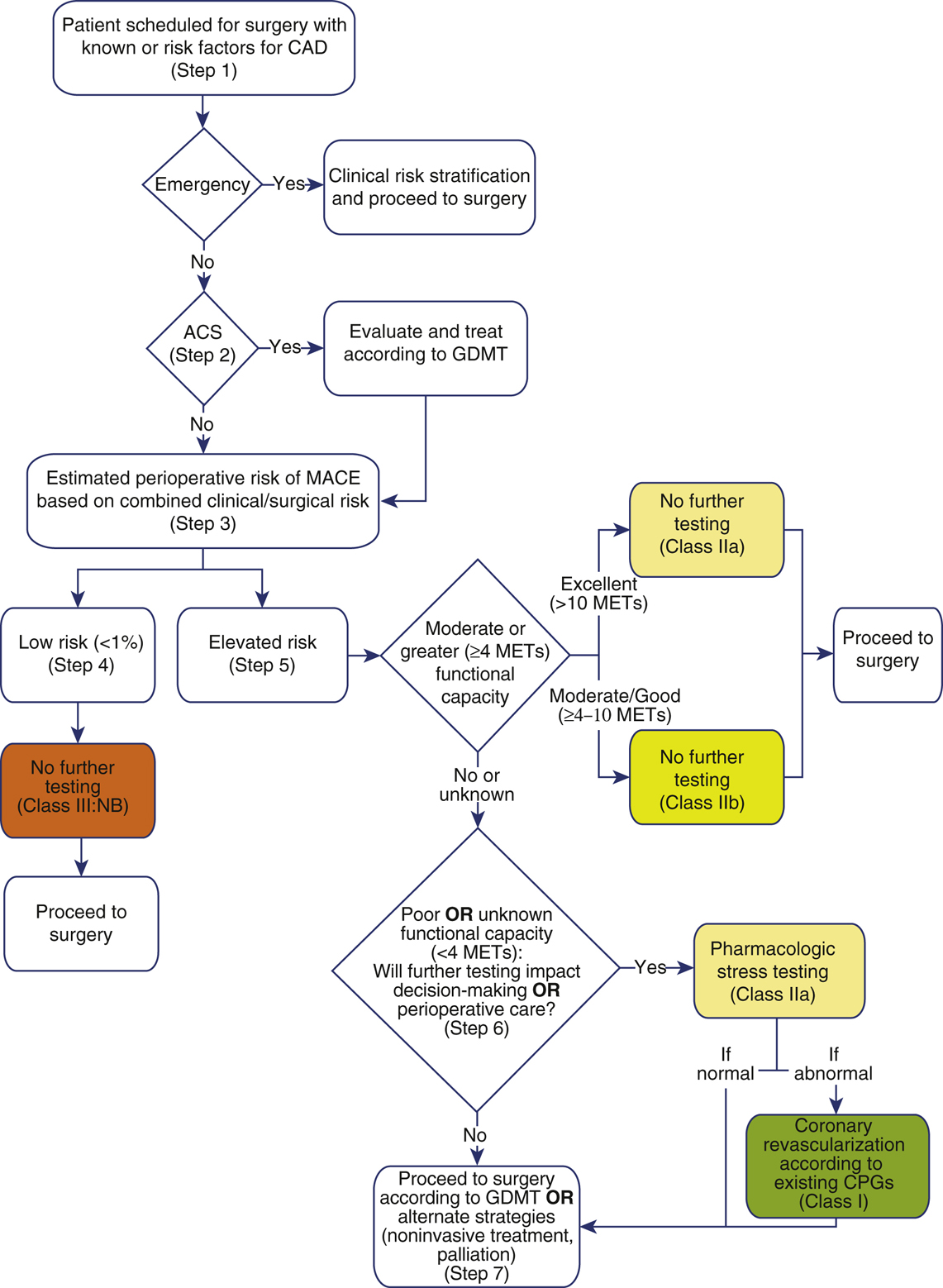

The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) have developed joint guidelines for the preoperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. The initial evaluation consists of the patient’s history, focused physical examination, and routine laboratory investigation. Based on the patient’s history, cardiac risk factors, functional status, and the nature of the surgical procedure, the ACC/AHA guidelines provide a stepwise approach for identifying patients who may benefit from further cardiovascular testing (Figure 3.2).

Figure 3-2 Stepwise approach to perioperative cardiac assessment for CAD from the latest ACC/AHA guidelines.

Colors correspond to classes of recommendations. ACC/AHA, American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CAD, coronary artery disease; CPGs, clinical practice guidelines; GDMT, guideline-directed medical therapy; MACE, major adverse cardiac event; METs, metabolic equivalents.

(Reprinted from Fleisher LA, FleischmannKE, AuerbachAD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(22):e77-e137. Copyright © 2014 American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association, Inc. With permission.)

- Initial screening

- The need for emergency surgery preempts further cardiac workup. The ACC/AHA guidelines define an emergency procedure as one that must be started within 6 hours. As there is little to no time, the patient must proceed often with no or very limited clinical preoperative evaluation. Emergent surgery should proceed with appropriate patient monitoring and management strategies based on the patient’s clinical risk factors for coronary artery disease (CAD). Bedside focused cardiac ultrasound (FoCUS) via transthoracic echocardiography can be performed to rule out life-threatening cardiac conditions such as tamponade, aortic dissection, or myocardial infarction (MI) to help with perioperative management in the emergent setting.

- If the surgery is not emergent, determine whether the patient has an acute coronary syndrome (ACS). An ACS is an unstable angina or an MI. The patient may present with chest pain, shortness of breath, diaphoresis, or nausea. The electrocardiogram (ECG) may show ST segment depressions or elevations. If the patient has an ACS, the surgical procedure should be postponed and the patient should immediately undergo cardiac evaluation and guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT). If the patient does not have an ACS, then proceed with an assessment of the patient’s postoperative risk for a major adverse cardiac event (MACE).

- Risk of MACE. The patient’s risk of MACE should be determined based on clinical characteristics and the surgical procedure. Clinical risk factors for MACE include a history of heart failure, CAD, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease. Validated risk prediction tools, such as the Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI) and the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) Surgical Risk Calculator (riskcalculator.facs.org), can be used to help predict the risk of perioperative MACE.

- If the patient has a low risk of MACE (<1%), then no further testing is needed and the patient may proceed to surgery.

- If the patient has an elevated risk of MACE (≥1%), then the functional capacity should be determined. Functional capacity can be expressed as metabolic equivalents (METs). A single MET represents oxygen consumption at rest. If the patient has moderate or excellent functional capacity without cardiac symptoms, then the patient may proceed to surgery without further evaluation. Moderate or excellent functional capacity is defined as an exercise capacity greater than or equal to 4 METs. Activities that correspond to moderate functional capacity include climbing two flights of stairs, walking on level ground at 4 mph, running a short distance, scrubbing floors, or playing a game of golf without a cart. The ability to participate in strenuous sports such as swimming, singles tennis, or football generally corresponds to excellent functional capacity.

- If the patient has poor or unknown functional capacity, then further testing may be needed if the results will change a patient’s management. Poor functional capacity is defined as an exercise capacity less than 4 METs. Examples include the inability to walk more than two blocks on level ground without stopping due to symptoms and activity limited to eating, dressing, and walking indoors. Further testing may include exercise or pharmacologic stress testing. If abnormal, coronary angiography may be considered. The patient can then proceed to surgery with GDMT. Testing may not be necessary if the results will not alter patient management.

- Supplemental cardiac evaluation. Supplemental cardiac evaluation should be performed when indicated to measure functional capacity, identify the presence of cardiac dysfunction, and provide an estimate of the perioperative cardiac risk.

- Preoperative resting 12-lead ECG should be considered for patients with known coronary heart disease, significant arrhythmia, peripheral arterial disease, cerebrovascular disease, or other structural heart diseases, except for those undergoing low-risk surgery. Routine preoperative ECG is not indicated for asymptomatic patients undergoing low-risk surgery.

- Rest echocardiography may be used to evaluate ventricular function in patients with history of heart failure or dyspnea of unknown origin. It is also useful to assess valvular pathology in patients with a history of valvular disease or a newly identified heart murmur.

- Stress testing is recommended for patients with elevated risk of MACE and poor or unknown functional capacity if outcome will change management. Patients who have an elevated risk of MACE and moderate to good (4-10 METs) functional capacity may proceed to surgery without stress testing. Routine screening with stress testing is not useful for patients undergoing low-risk noncardiac surgery.

- Exercise stress testing provides an objective measure of functional capacity. It is the preferred modality in patients who are capable of achieving adequate workloads. Sensitivity and specificity for multivessel CAD are 81% and 66%, respectively. Exercise stress tests are highly predictive when ST segment changes are characteristic of ischemia (>2 mm, sustained into recovery, and/or associated with hypotension). The risk of perioperative cardiac events is increased significantly in patients who have abnormal exercise ECGs at low workloads. Radionuclide imaging or echocardiography can be combined with exercise stress testing for patients whose baseline ECGs render interpretation invalid.

- Pharmacologic stress testing can be conducted with either an agent that increases myocardial oxygen demand (dobutamine) or dilates coronary arteries and causes coronary steal from diseased vessels (dipyridamole or adenosine). Pharmacologic stress tests are suitable for patients who are unable to exercise. Dobutamine stress testing is typically combined with echocardiography to detect wall motion abnormalities brought about by the increased myocardial workload. Dipyridamole or adenosine stress tests are typically combined with radionuclide imaging to detect areas of myocardium that are at risk. Pharmacologic vasodilation has the risk of a false-negative test in patients with multivessel CAD where all vessels are already maximally vasodilated. In both cases, perioperative cardiac risk is directly proportional to the extent of myocardium that is found to be at risk on imaging.

- Cardiac catheterization is considered the “gold standard” for evaluating CAD. Information obtained includes coronary anatomy with visualization of direction and distribution of flow, hemodynamics, and overall function of the heart. Routine preoperative coronary angiography is not recommended. Revascularization before noncardiac surgery is recommended in circumstances in which revascularization is indicated according to existing clinical practice guidelines.

- Noninvasive imaging including cardiac MRI (CMR) and coronary computed tomography angiogram (CCTA) have emerged as reasonable options for preoperative cardiac evaluation. CMR is usually reserved for patients after first-line imaging (echocardiography) is either inconclusive or indeterminant; it is generally reserved for patients with complex disease. Contraindications to CMR include the presence of implants or cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) that are not MRI safe. CCTA can be utilized to rule out obstructive CAD in low- to medium-risk patients, but it is not advised for high-risk patients; coronary catheterization remains the gold standard for high-risk patients. Contraindications to cardiac CTA include renal failure or allergy to contrast.

- Cardiac consultation may be helpful in determining which tests will be useful and in interpreting the results. The consultant can help optimize the patient’s preoperative medical therapy and provide follow-up in the postoperative period. Such follow-up is crucial with the initiation of new drug therapies and often for patients with pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) devices (see Section XI).

- Indications for preoperative coronary revascularization with either coronary artery bypass grafting or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) are in general the same as in the nonoperative setting. Surgery, in and of itself, is not an indication for coronary revascularization, regardless of extent of vessel disease or left ventricular dysfunction.