Author(s): EvanHodell, StephanieLankford, IlanMizrahi

Rapid assessment of injuries and institution of resuscitative measures are particularly important in trauma patients. Life-threatening injuries should be identified immediately based on Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability (neurologic evaluation) and Exposure (hypothermia, smoke inhalation, chemical substances). Treatment measures should be initiated simultaneously. Assume that all patients have a cervical spine injury, a full stomach, and hypovolemia until proven otherwise.

- Airway

- Airway assessment should include inspection for foreign bodies, facial and laryngeal fractures (palpable fracture and subcutaneous emphysema), and expanding cervical hematomas. Dyspnea, hemoptysis, dysphonia, stridor, and air leaking through the neck wound may also be signs of airway injury. Remove all secretions, blood, vomitus, and any existing foreign bodies (eg, dentures or teeth).

- Minimize movement of the cervical spine during airway manipulation. If immobilizing devices must be removed temporarily, an assistant should keep the head in a neutral position with manual in-line stabilization.

- Establish a definitive airway if there is any doubt about the patient’s ability to maintain airway integrity. With blunt or penetrating injuries to the neck, endotracheal intubation may worsen a laryngeal or bronchial injury. Functional suction equipment should always be immediately available to prevent aspiration if the trauma patient with a full stomach vomits.

- The awake patient. Depending on the patient’s injuries, the ability to cooperate, and cardiopulmonary stability, several options are available. Choice of technique for securing the airway should be individualized based on operator preference and level of experience, as well as patient circumstances.

- Intubation after a rapid sequence induction is the most common approach to the airway. Video laryngoscopy may be helpful in patients with suspected cervical spine injury.

- Awake nasal or orotracheal intubation with the use of a laryngoscope or fiberoptic bronchoscope is an alternative.

- Blind nasal intubation may be performed on the spontaneously breathing patient.

- Awake cricothyroidotomy or tracheostomy may be necessary for patients with severe facial trauma that might be contraindications to other methods of intubation.

- The combative patient. A rapid sequence orotracheal intubation is often the most expedient approach. Preoxygenation may be difficult, and any delay in securing the airway will cause progressive hypoxemia.

- The unconscious patient. Orotracheal intubation is usually the safest and most expeditious approach.

- The patient with a prehospital supraglottic airway. If the patient arrives with a supraglottic airway, prioritize establishing a definitive airway with endotracheal intubation. Ventilating via a supraglottic airway may force air into the stomach, leading to gastric inflation and subsequent emesis. Common prehospital supraglottic airways include Laryngeal Mask Airways, King Laryngeal Tubes, and Combitubes.

- The intubated patient. Verify the position of an endotracheal tube by auscultating for breath sounds bilaterally and by detecting end-tidal CO2. Secure the endotracheal tube, and ensure adequate ventilation and oxygenation. If there are any problems with oxygenation, consider bronchoscopy to assess endotracheal tube placement and patency.

- The awake patient. Depending on the patient’s injuries, the ability to cooperate, and cardiopulmonary stability, several options are available. Choice of technique for securing the airway should be individualized based on operator preference and level of experience, as well as patient circumstances.

- Breathing. Adequate function of the lungs, diaphragm, and chest wall should be evaluated rapidly. Supplemental oxygen should be provided to all trauma patients, either by mask or by endotracheal tube.

- Assess the chest wall excursion. Auscultate the lungs to ensure adequate gas exchange. Visual inspection and palpation may rapidly detect injuries such as a pneumothorax.

- Tension pneumothorax, massive hemothorax, and pulmonary contusion are three common conditions that may acutely impair ventilation and should always be identified.

Treatment of tension pneumothorax. Perform needle decompression on the affected side with a large-bore 14-gauge, 3.25-inch/8-cm catheter in the fourth or fifth intercostal space, anterior axillary line. The second intercostal space at the mid-clavicular line is the primary site in children and secondary site in adults. Effective treatment will result in a normalization of physiologic parameters but rarely cause the classically taught “whoosh” of air.

- Positive-pressure ventilation may worsen a tension pneumothorax and/or cardiac tamponade, which can rapidly lead to cardiovascular collapse.

- Lung protective ventilation. Use tidal volumes of 6 to 8 mL/kg. In patients with metabolic acidosis or suspected traumatic brain injury, increase the respiratory rate to achieve a PaCO2 of 35 to 40 mm Hg. In patients with hemorrhagic shock, be wary that high levels of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) and auto-PEEP will increase intrathoracic pressure and subsequently decrease venous return, cardiac output, and systemic blood pressure.

- The trauma patient’s breathing and gas exchange should continue to be periodically reevaluated after intubation or initiation of positive-pressure ventilation.

- Circulation

- In the severely injured trauma patient, rapid initiation of resuscitation measures is important to prevent and control the lethal triad: hypothermia, acidosis, and coagulopathy.

- Hemodynamics are initially assessed by palpating pulses and measuring the blood pressure. Consider placing an intra-arterial catheter for continuous blood pressure measurement in unstable patients.

- Intravenous (IV) access. Check IV lines already in place to ensure proper function. At least two large-bore catheters should be placed, preferably 16 gauge or larger. These lines should be placed above the level of the diaphragm in patients with injuries of the abdomen, where there is a potential for major venous disruption. IV access below the level of the diaphragm is helpful when obstruction or disruption of the superior vena cava, innominate, or subclavian vein is suspected.

- Peripheral venous cannulation failure. In this event, percutaneous subclavian or femoral vein cannulation should be carried out. Although the internal and external jugular veins remain options, access to these structures is frequently hindered by immobilization of the head and neck for a suspected cervical spine injury. If these approaches prove unsuccessful, surgical cutdowns can be performed. The saphenous vein at the ankle and the antecubital venous system are acceptable options. When emergent access for vasoactive medications or fluid resuscitation is needed, intraosseous (IO) access to the vasculature is also an option for personnel trained in this technique.

- IO access locations: proximal tibia (most common), distal tibia, proximal humerus, iliac crest, and sternum.

- IO flowrates vary by site but are roughly 165 mL/min and can be optimized by initially flushing the line and then using a pressure bag. In awake patients, flushing the line under pressure is usually much more painful than initial placement.

- IO access can be used for blood and fluid resuscitation, as well as vasoactive medications.

- Volume resuscitation should be individualized. The concept of “damage control” emphasizes multiple approaches to control and prevent tissue hypoperfusion, acidosis, coagulopathy, and hypothermia.

- Damage control resuscitation (DCR) refers to the strategy of limiting crystalloid use, early resuscitation with packed red blood cells and clotting factors, and maintenance of a systolic blood pressure at approximately 90 mm Hg or mean arterial pressure at 50 to 65 mm Hg. The disadvantages to crystalloid infusion include dilution of coagulation factors, hemodilution, and clot disruption. Early administration of blood and clotting factors serves to treat trauma-induced coagulopathy that can occur early after injury. In a patient in whom hemorrhage has not been definitely controlled, elevation in blood pressure and cardiac output can cause dislodgement of a clot and further bleeding. DCR blood pressure parameters should not be used in certain subsets of patients, such as patients with head trauma. Avoiding hypotension is a priority in patients with moderate and severe traumatic brain injury. In this patient population, maintain a systolic blood pressure ≥100 mm Hg for patients 50 to 69 years old and ≥110 mm Hg for patients 15 to 49 or >70 years old.

- Massive blood transfusion, or the replacement of 50% of the total blood volume within 3 hours, is a response to massive and uncontrolled hemorrhage. In an emergency, type-specific uncross-matched blood or type O–negative blood may be given before cross-matched blood becomes available. A ratio of 1:1:1 or 2:1:1 (RBCs:plasma:platelets) is targeted for blood product administration. Although this ratio mirrors the content of whole blood, superior clot formation is achieved with transfusion of whole blood compared with 1:1:1 component transfusion. Therefore, fresh whole blood has been used for combat injuries in the military. Some civilian institutions have now adopted its use in trauma. An intraoperative blood salvage system (cell saver) can also be used to help in the reduction of allogenic red blood cell administration. Aggressive resuscitation with blood products can lead to hypothermia, hyperkalemia, and hypocalcemia. Empiric treatment is often indicated as the laboratory results may lag behind the clinical scenario when massive transfusion resuscitation is undertaken.

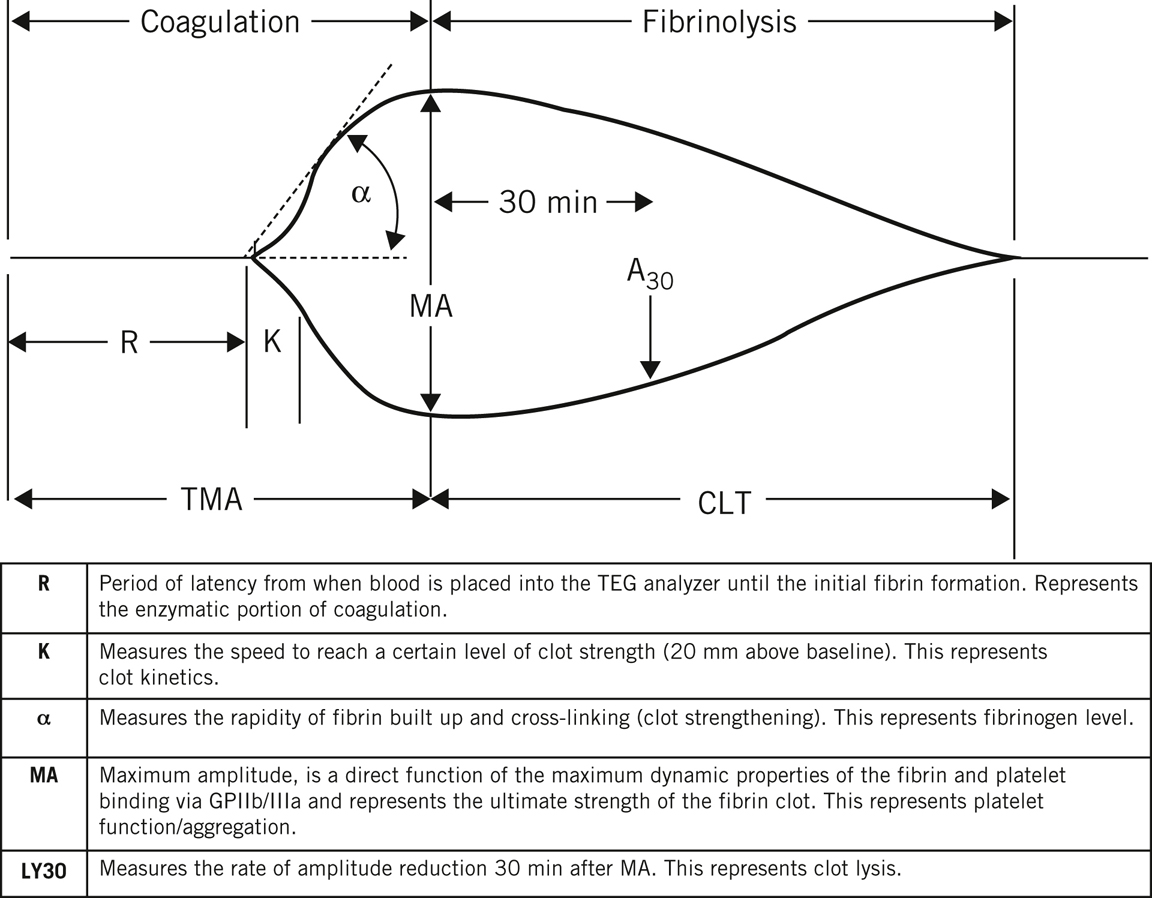

- Management of coagulopathy is guided by point-of-care (POC) and standard laboratory testing. POC tests, such as the thromboelastogram (Figure 35.1), provide rapid, near-real-time information regarding clot initiation, kinetics of clot formation, clot strength, and fibrinoloysis. Standard tests of hemoglobin levels, platelet counts, fibrinogen levels, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and international normalized ratio are useful but may lag behind rapidly evolving clinical situations. Utilizing dynamic parameters, such as transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) and the intra-arterial pressure waveform, can also assist in judicious blood and fluid administration.

Figure 35-1 Overview of thromboelastogram parameters.

(Reprinted with permission from Handa RR, TurnbullIR, IsmailO. Hemostasis, anticoagulation, and transfusions. In: KlingensmithME, WisePE, CourtneyCM, et al, eds. The Washington Manual of Surgery. 8th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2019. Figure 6.2.)

- Severely injured trauma patients do not tolerate prolonged surgical procedures. Damage control surgery refers to the concept of employing initial short surgical procedures immediately after injury with the goals of controlling hemorrhage and preventing contamination (eg, due to GI tract injury) through temporary measures. Patients then undergo definitive corrective surgery at a later date after they have been stabilized.

- Vasopressor infusions should not substitute for adequate volume replacement during initial resuscitation. Vasopressors may be necessary as a temporizing measure if perfusion pressure is clearly inadequate during ongoing volume resuscitation.

- Antifibrinolytics, such as tranexamic acid (TXA), can reduce mortality in a bleeding trauma patient when started as soon as possible within 3 hours of injury. The safety of antifibrinolytics after 3 hours has yet to be fully elucidated. Immediate antifibrinolytic therapy is also associated with a decrease in mortality in patients presenting with traumatic brain injury. Administer 1 g of TXA over 10 minutes, followed by an intravenous infusion of 1 g over 8 hours.

- Disability/neurologic evaluation. A brief neurologic examination yields useful information in assessing cerebral perfusion or oxygenation and can provide a simple and quick means of predicting a patient’s outcome.

- The level of consciousness can be described by the AVPU method (A, alert; V, responds to verbal stimuli; P, responds only to painful stimuli; and U, unresponsive to all stimuli). A more detailed and quantitative assessment of neurologic function is with the Glasgow coma scale (Table 35.1) that is the sum of the best eye opening, verbal, and motor responses.

Table 35-1 Glasgow Coma Score

Eye Opening Score Spontaneous 4 To speech 3 To pain 2 No response 1 Best Verbal Response Oriented 5 Confused conversation 4 Inappropriate words 3 Incomprehensible sounds 2 None 1 Best Motor Response Obeys commands 6 Localizes pain 5 Normal flexion (withdrawal) 4 Abnormal flexion (decorticate) 3 Extension (decerebrate) 2 None (flaccid) 1 - An altered level of consciousness dictates immediate reevaluation of the patient’s oxygenation and circulation, even though it can be of central nervous system origin (trauma or intoxication).

- Neurologic deterioration can rapidly occur in trauma patients and necessitates frequent neurologic reevaluation.

- The level of consciousness can be described by the AVPU method (A, alert; V, responds to verbal stimuli; P, responds only to painful stimuli; and U, unresponsive to all stimuli). A more detailed and quantitative assessment of neurologic function is with the Glasgow coma scale (Table 35.1) that is the sum of the best eye opening, verbal, and motor responses.

- Exposure. Trauma patients are often hypothermic upon arrival at the hospital and require aggressive efforts to maintain normothermia (temperature ≥35.5 °C). Hypothermia can exacerbate coagulopathy.

- External warming devices should be applied, IV fluids and blood products warmed before infusion, and a warm environment maintained.

- If there is any suspicion of exposure to chemical agents, decontamination of the patient must be carried out before entrance into the hospital. This terminates exposure, protects the health care provider, and allows the hospital to function effectively.

- Diagnostic studies

- Laboratory studies include blood type and cross-match, complete blood count, platelet count, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, electrolytes, glucose, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, urinalysis, and, if indicated, toxicologic screening.

- Radiographic studies should include a lateral cervical spine film, a chest radiograph (CXR), and an anteroposterior view of the pelvis on all patients with blunt trauma. At a minimum, a CXR is obtained in all patients with penetrating injuries of the trunk. Additional studies include thoracic, lumbar, and sacral spine films and chest and abdominal computed tomography (CT) studies.

- Lateral radiographs of the cervical spine must include the C7–T1 interface and must be of sufficient quality to delineate the structures of interest (ie, soft tissues and bones).

- If the patient’s clinical condition allows time for additional studies, open-mouth odontoid and anteroposterior views of the neck (standard trauma cervical spine series) may be obtained.

- If the clinical evaluation demonstrates a patient with significant neck pain and tenderness but no evidence of fracture or dislocation on the plain radiographs, CT and magnetic resonance imaging may help delineate an occult injury.

- A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) should be performed on all major trauma patients to help evaluate the presence of myocardial injury (eg, contusion, tamponade, ischemia, and arrhythmia).

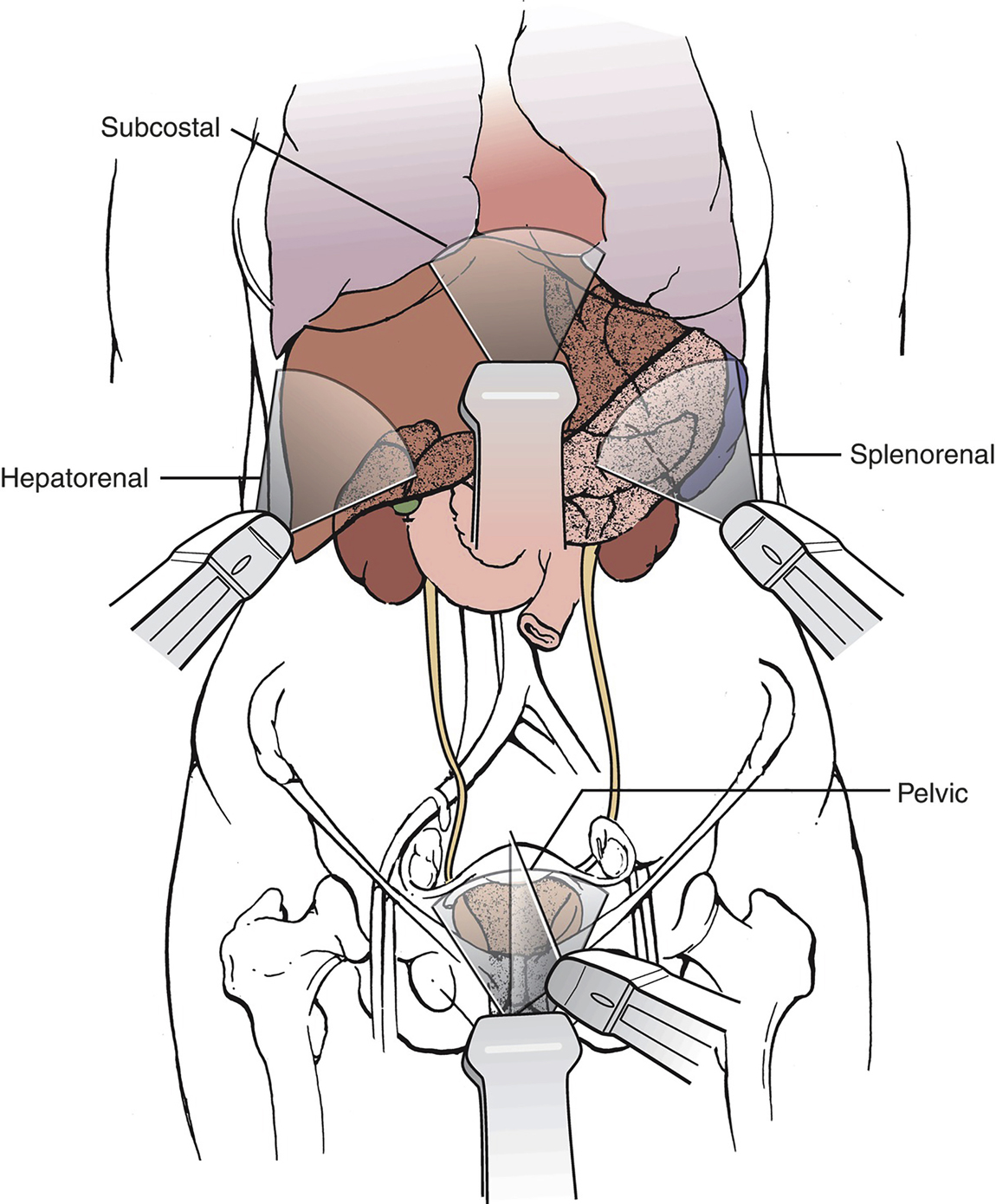

- Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (FAST,Figure 35.2) is a rapid ultrasound examination evaluating for bleeding or free fluid around the heart or abdominal organs. The four areas that are examined are the perihepatic space (including Morison’s pouch or hepatorenal recess), perisplenic space, pelvis, and pericardium. A negative FAST examination, however, cannot completely rule out significant intraperitoneal bleeding in patients with blunt abdominal trauma.

Figure 35-2 FAST examination ultrasound locations.

(Reprinted with permission from Berg SM, BittnerEA, ZhaoKH. Anesthesia Review: Blasting the Boards. Wolters Kluwer; 2016. Figure 19.1.)

- The extended FAST (eFAST) examination includes the ultrasound examination of a patient’s bilateral lungs. It can be used to detect a pneumothorax with the absence of normal lung sliding.

- Monitoring is dictated by the severity of the patient’s injuries and preexisting medical problems.

- An arterial line is useful in patients with hemodynamic instability or respiratory failure.

- A central venous catheter (CVC) may be required to assess volume status via central venous pressure (CVP) measurements. Vasoactive medications can also be administered through a CVC.

- A pulmonary artery catheter may be helpful in patients with ventricular dysfunction, severe coronary artery disease, valvular heart disease, multiple organ system involvement, or hemodynamics that seem disproportionate to their trauma burden. Placement is planned according to the time available and the clinical status of the patient.