1 Dr. Brown and Dr. Shvartsman are employees of the Uniformed Services University (USU). The opinions and assertions expressed in this chapter are Dr. Brown's and Dr. Shvartsman's and do not reflect the official policy or position of the USU or the Department of Defense.

| ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS | ||

|

General Considerations

Normal menstrual frequency varies from 24 to 38 days with bleeding lasting an average of 5 days (range, 2-8 days) and a mean blood loss of 40 mL per cycle. AUB refers to menstrual bleeding of abnormal quantity, duration, or schedule in nonpregnant reproductive age patients. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) introduced the classification system for AUB in 2011, which was then endorsed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. This classification system pairs AUB with descriptive terms denoting the bleeding pattern (ie, heavy, light, menstrual, intermenstrual) and etiology (the acronym PALM-COEIN standing for Polyp, Adenomyosis, Leiomyoma, Malignancy and hyperplasia, Coagulopathy, Ovulatory dysfunction, Endometrial, Iatrogenic, and Not yet classified) (eTable 20-1. Palm-Coein Classification System for the Causes of Abnormal Uterine Bleeding (AUB) in Nonpregnant Women of Reproductive Age). In adolescents, AUB often occurs because of persistent anovulation due to the immaturity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. AUB in patients aged 19-39 years is often a result of structural lesions, anovulatory cycles, use of hormonal contraception, or endometrial hyperplasia.

eTable 20-1. PALM-COEIN classification system for the causes of abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) in nonpregnant women of reproductive age.| Structural Causes: PALM | Nonstructural Causes: COEIN |

|---|---|

Polyp (AUB-P) Adenomyosis (AUB-A) Leiomyoma (AUB-L) - Submucosal myoma (AUB-Lsm)

- Other myoma (AUB-Lo)

Malignancy and Hyperplasia (AUB-M) |

Coagulopathy (AUB-C) Ovulatory dysfunction (AUB-O) Endometrial (AUB-E) Iatrogenic (AUB-I) Not yet classified (AUB-N) |

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

The diagnosis depends on the following: (1) confirming a uterine source of the bleeding; (2) excluding pregnancy and confirming patient is premenopausal; (3) ascertaining whether the bleeding pattern suggests regular ovulatory bleeding or anovulatory bleeding; (4) determining the contribution of structural abnormalities (PALM), including risk for malignancy/hyperplasia; (5) identifying risk of medical conditions that may impact bleeding (eg, inherited bleeding disorders, endocrine disease, risk of infection); and (6) assessing the contribution of medications, including contraceptives, anticoagulants, and natural product supplements that may affect bleeding.

B. Laboratory Studies

A CBC, pregnancy test, and thyroid tests should be done. For adolescents with heavy menstrual bleeding and adults with a positive screening history for bleeding disorders, coagulation studies should be considered, including a von Willebrand panel for adolescents, since up to 18% of persons with severe heavy menstrual bleeding have an underlying coagulopathy. For patients with irregular bleeding and prolonged time between menses, checking serum prolactin and FSH levels may be useful. Vaginal or urine samples should be obtained for testing to rule out infectious causes. If indicated, cervical cytology should also be obtained.

C. Imaging

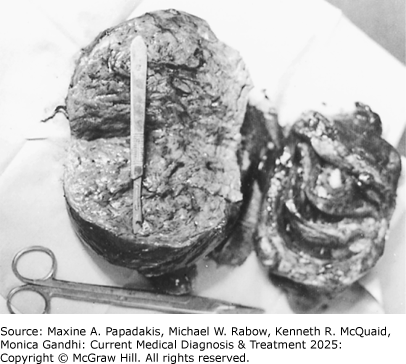

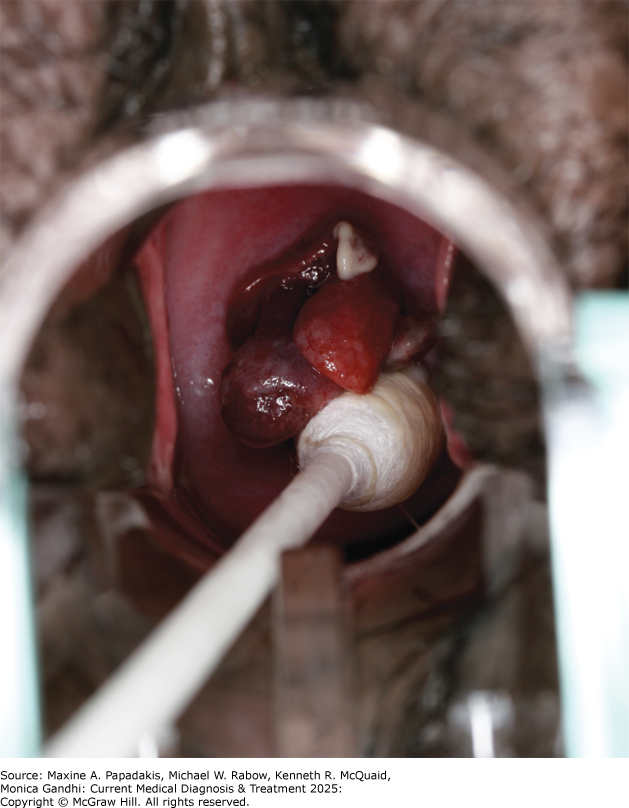

Transvaginal ultrasound is useful to assess for the presence of fibroids and suspicion of adenomyosis, as well as to evaluate endometrial thickness for potential hyperplasia or endometrial cancer. Sonohysterography or hysteroscopy may help to diagnose endometrial polyps or subserous myomas (eFigures 20-1, 20-2, 20-3). MRI is not a primary imaging modality for AUB but can more definitively diagnose submucous myomas (eFigure 20-3) and adenomyosis.

eFigure 20-1. Cervical Polyps

Cervical polyps. Several finger-like growths protruding from the cervical os. (Reproduced with permission, from Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

D. Endometrial Sampling

The purpose of endometrial sampling is to determine if hyperplasia or carcinoma is present. Sampling methods and other gynecologic diagnostic procedures are described in Table 20-1. Common Gynecologic Diagnostic Procedures (Listed in Alphabetical Order). Polyps, endometrial hyperplasia and, occasionally, submucous myomas are identified on endometrial biopsy. Endometrial sampling should be performed in patients with AUB who are 45 years or older, or in younger patients with a history of unopposed estrogen exposure (including obesity or chronic ovulatory dysfunction) or failed medical management and persistent AUB.

Table 20-1. Common gynecologic diagnostic procedures (listed in alphabetical order).Colposcopy Visualization of cervical, vaginal, or vulvar epithelium under 5-50 × magnification with and without dilute acetic acid to identify abnormal areas requiring biopsy. An office procedure. Dilation & curettage (D&C) Dilation of the cervix and curettage of the entire endometrial cavity, using a metal curette or suction cannula and often using forceps for the removal of endometrial polyps. Can usually be done in the office under local anesthesia or in the operating room under sedation or general anesthesia. D&C is often combined with hysteroscopy for improved sensitivity. Endometrial biopsy Blind sampling of the endometrium by means of a curette or small aspiration device without cervical dilation. Diagnostic accuracy similar to D&C. An office procedure performed with or without local anesthesia. Endocervical curettage Removal of endocervical epithelium with a small curette for diagnosis of cervical dysplasia and cancer. An office procedure performed with or without local anesthesia. Hysterosalpingography Injection of radiopaque dye through the cervix to visualize the uterine cavity and oviducts. Mainly used in investigation of infertility or to identify a space-occupying lesion. Hysteroscopy Visual examination of the uterine cavity with a small fiberoptic endoscope passed through the cervix. Curettage, endometrial ablation, biopsies of lesions, and excision of myomas or polyps can be performed concurrently. Can be done in the office under local anesthesia or in the operating room under sedation or general anesthesia. Greater sensitivity for diagnosis of uterine pathology than D&C. Laparoscopy Visualization of the abdominal and pelvic cavity through a small fiberoptic endoscope passed through a subumbilical incision. Permits diagnosis, tubal sterilization, and treatment of many conditions previously requiring laparotomy. General anesthesia is used. Saline infusion sonohysterography Introduction of saline solution into endometrial cavity with a catheter to visualize submucous myomas or endometrial polyps by transvaginal ultrasound. May be performed in the office with oral or local analgesia, or both. |

Treatment

Treatment for patients with AUB depends on the etiology of the bleeding, determined by history, physical examination, laboratory findings, imaging, and endometrial sampling. Patients with AUB due to structural abnormalities (eg, submucosal myomas, endometrial polyps, or pelvic [endometrial] neoplasms) or bleeding diathesis may require targeted therapy. A large proportion of perimenopausal patients, however, have ovulatory dysfunction AUB (AUB-O).

Treatment for AUB-O should include consideration of potentially contributing medical conditions, such as thyroid dysfunction. Often AUB-O can be treated hormonally. For patients amenable to using contraceptives, estrogen-progestin contraceptives and the 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing IUD are both effective treatments. The choice between the two depends on whether any contraindications to these treatments exist and on patient preference. Oral or injectable progestin-only medications are also generally effective, but there is little consensus on optimal regimens, and they appear to be less effective than other medical therapies like the hormonal IUD and tranexamic acid. Nonhormonal options include NSAIDs, such as naproxen or mefenamic acid, in the usual anti-inflammatory doses taken during menses, and tranexamic acid 1300 mg three times per day orally for up to 5 days. Both have been shown to decrease menstrual blood loss by about 40%, with tranexamic acid superior to NSAIDs in direct comparative studies.

Patients experiencing heavier bleeding can be given a taper of any of the combination oral contraceptives (with 30-35 mcg of ethinyl estradiol) to control the bleeding. There are several commonly used contraceptive dosing regimens, including one pill three times daily (every 8 hours) for 1 or 2 days followed by one pill twice daily through day 5 and then one pill daily through day 20; after withdrawal bleeding occurs, pills are taken in the usual dosage for three cycles. In cases of heavy bleeding requiring hospitalization, intravenous conjugated estrogens, 25 mg every 4 hours for three or four doses, can stop acute bleeding. This can be followed by oral conjugated estrogens, 2.5 mg daily, or ethinyl estradiol, 20 mcg orally daily, for 3 weeks, with the addition of medroxyprogesterone acetate, 10 mg orally daily for the last 10 days of treatment, or a combination oral contraceptive daily for 3 weeks. This will stabilize the endometrium and control the bleeding.

For patients with AUB and ineffective results from medical management or who do not desire medical management, surgical options can be considered. Heavy menstrual bleeding due to structural lesions (eg, fibroids, adenomyosis, polyps) is the most common indication for surgery. Minimally invasive procedural options for fibroids include uterine artery embolization and focused ultrasound ablation. Surgical options include myomectomy or hysterectomy. For adenomyosis, the definitive treatment is hysterectomy. Polyps can often be excised hysteroscopically. For women without structural abnormalities, endometrial ablation has similar results compared to the 52-mg levonorgestrel IUD in reducing menstrual blood loss. Hysteroscopic surgical approaches include endometrial ablation with electrocautery or less commonly laser photocoagulation. Nonhysteroscopic techniques available in the United States include impedance bipolar radiofrequency ablation, cryoablation, circulating free-fluid thermal ablation, combined thermal and radiofrequency ablation, and vapor ablation. The latter methods are well-adapted to outpatient therapy under local anesthesia. While hysterectomy was used commonly in the past for bleeding unresponsive to medical therapy, the low risk of complications and the good short-term results of both endometrial ablation and hormonal IUD make them attractive alternatives to hysterectomy.

Management options for endometrial hyperplasia without atypia include surveillance, oral contraceptives, or progestin therapy. Surveillance may be used if the risk of occult cancer or progression to cancer is low, and the inciting factor (eg, anovulation) has been eliminated. Therapy may include cyclic or continuous progestin therapy (medroxyprogesterone acetate, 10-20 mg/day orally, or norethindrone acetate, 15 mg/day orally) or using a hormonal IUD. Repeat sampling should be performed if symptoms recur. Hysterectomy is the preferred treatment for endometrial hyperplasia with atypia (also called endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia) or carcinoma of the endometrium. In some patients with endometrial hyperplasia with atypia, progestin therapy with scheduled repeat endometrial sampling may be an alternative to hysterectomy. Patients who elect this approach include those who desire future childbearing or those who are not candidates for surgery.

When to Refer

- If bleeding is not controlled with first-line therapy.

- If expertise is needed for a surgical procedure.

When to Admit

If bleeding is uncontrollable with first-line therapy or the patient is not hemodynamically stable.

BelcaroCet al. Comparison between different diagnostic strategies in low-risk reproductive age and pre-menopausal women presenting abnormal uterine bleeding. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10:884. [PMID: 33142970] Bofill RodriguezMet al. Cyclical progestogens for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;8:CD001016. [PMID: 31425626] Bryant-SmithACet al. Antifibrinolytics for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;4:CD000249. [PMID: 29656433] LebduskaEet al. Abnormal uterine bleeding. Med Clin North Am. 2023;107:235. [PMID: 36759094] MunroMGet al; FIGO Menstrual Disorders Committee. The two FIGO Systems for normal and abnormal uterine bleeding symptoms and classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years: 2018 revisions. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;143:393. [PMID: 30198563] MunroMGet al; FIGO Committee on Menstrual Disorders and Related Health Impacts, and FIGO Committee on Reproductive Medicine, Endocrinology, and Infertility. The FIGO ovulatory disorders classification system. Fertil Steril. 2022;118:768. [PMID: 35995633] SinghSet al. SOGC Clinical Practice Guideline No. 292. Abnormal uterine bleeding in pre-menopausal women. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018;40:e391. [PMID: 29731212] WoukNet al. Abnormal uterine bleeding in premenopausal women. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99:435. [PMID: 30932448] |