Diagnosis & Evaluation

A. Examination of the Patient

Two helpful clinical clues for diagnosing arthritis are the joint pattern and the presence or absence of extra-articular manifestations. The joint pattern is defined by the answers to three questions: (1) Is inflammation present? (2) How many joints are involved? and (3) What joints are affected? Joint inflammation manifests as warmth, swelling, and morning stiffness of at least 30 minutes' duration. Overlying erythema occurs with the intense inflammation of crystal-induced and septic arthritis. Both the number of affected joints and the specific sites of involvement affect the differential diagnosis (Table 22-1. Diagnostic Value of the Joint Pattern). Some diseases-gout, for example-are characteristically monoarticular, whereas other diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), are usually polyarticular. The location of joint involvement can also be distinctive. Only two diseases frequently cause prominent involvement of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint: osteoarthritis and psoriatic arthritis. Extra-articular manifestations such as fever (eg, gout, Still disease, endocarditis, vasculitis, SLE), rash (eg, SLE, psoriatic arthritis, inflammatory myositis), nodules (eg, RA, gout), or neuropathy (eg, vasculitis) narrow the differential diagnosis further.

Table 22-1. Diagnostic value of the joint pattern.| Characteristic | Status | Representative Disease |

|---|---|---|

| Inflammation | Present Absent | Rheumatoid arthritis, SLE, gout Osteoarthritis |

| Number of involved joints | Monoarticular Oligoarticular (2-4 joints) Polyarticular (≥ 5 joints) | Gout, trauma, septic arthritis, Lyme disease, osteoarthritis Reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, IBD Rheumatoid arthritis, SLE |

| Site of joint involvement | Distal interphalangeal Metacarpophalangeal, wrists First metatarsal phalangeal | Osteoarthritis, psoriatic arthritis (not rheumatoid arthritis) Rheumatoid arthritis, SLE, calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease (not osteoarthritis) Gout, osteoarthritis |

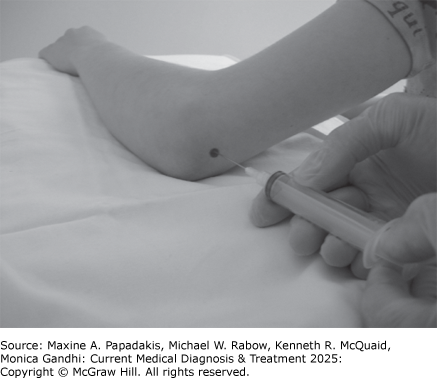

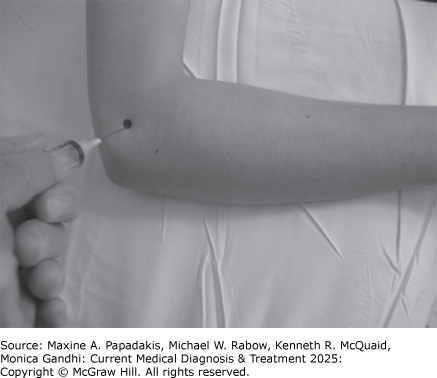

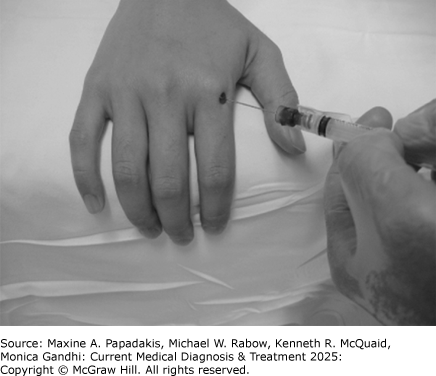

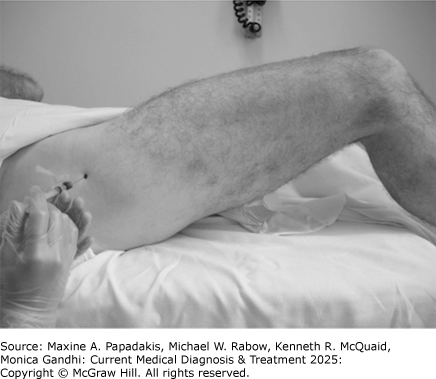

B. Arthrocentesis and Examination of Joint Fluid

If the diagnosis is uncertain, synovial fluid should be examined whenever possible (Table 22-2. Examination of Joint Fluid). Most large joints are easily aspirated, and contraindications to arthrocentesis are few (eFigures 22-1, 22-2, 22-3, 22-4, 22-5, 22-6, 22-7). The aspirating needle should never be passed through an overlying cellulitis or psoriatic plaque because of the risk of introducing infection. For patients who are receiving DOACs or long-term anticoagulation therapy with warfarin, joints can be aspirated with a small-gauge needle (eg, 22F); the INR should be less than 3.0 for patients taking warfarin.

Table 22-2. Examination of joint fluid.| Measure | (Normal) | Group I (Noninflammatory) | Group II (Inflammatory) | Group III (Purulent) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume (mL) (knee) | <3.5 | Often >3.5 | Often >3.5 | Often >3.5 |

| Clarity | Transparent | Transparent | Translucent to opaque | Opaque |

| Color | Clear | Yellow | Yellow to opalescent | Yellow to green |

| WBC per mcL | <200 (0.2 × 109 /L) | <2000 (2.0 × 109 /L) | 2000-75,0001 (2.0-75.0 × 109 /L) | >100,0002 (100 × 109 /L) |

| Polymorphonuclear leukocytes | <25% | <25% | 50% or more | 75% or more |

| Culture | Negative | Negative | Negative | Usually positive2 |

1 Gout, rheumatoid arthritis, and other inflammatory conditions occasionally have synovial fluid WBC counts >75,000/mcL (75 × 109 /L) but rarely >100,000/mcL (100 × 109 /L).

2 Most purulent effusions are due to septic arthritis. Septic arthritis, however, can present with group II synovial fluid, particularly if infection is caused by organisms of low virulence (eg, Neisseria gonorrhoeae) or if antibiotic therapy has been started.

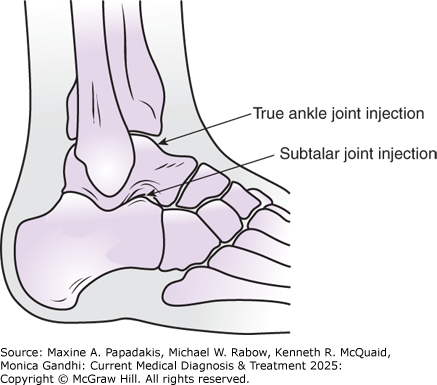

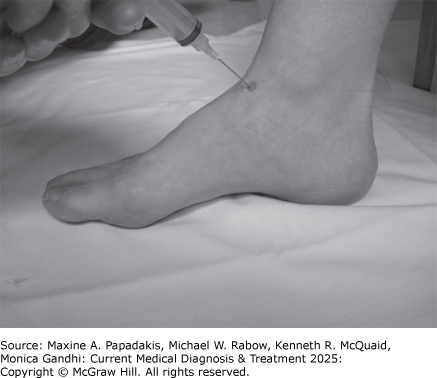

eFigure 22-1. A: Lateral View of the Ankle

A: Lateral view of the ankle. B: Injection of the true ankle joint, just medial to the extensor hallucis longus. C: Injection of the subtalar joint, just inferior and anterior to the tip of the lateral malleolus. (Used, with permission, from Imboden JB et al. Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Rheumatology, 3e. McGraw-Hill, 2013.)

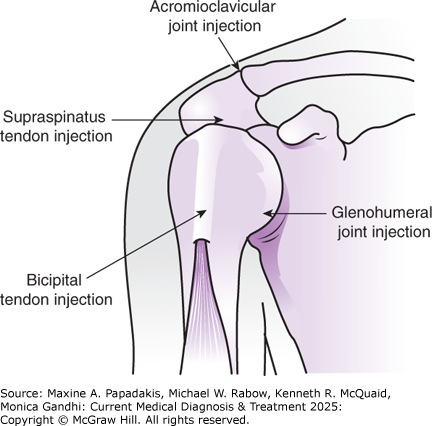

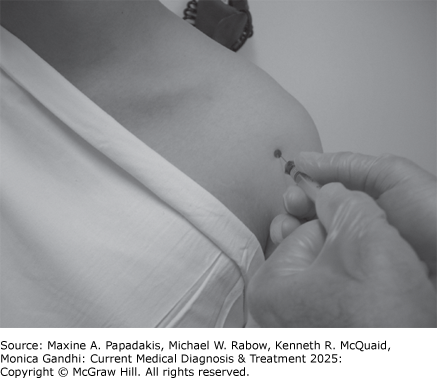

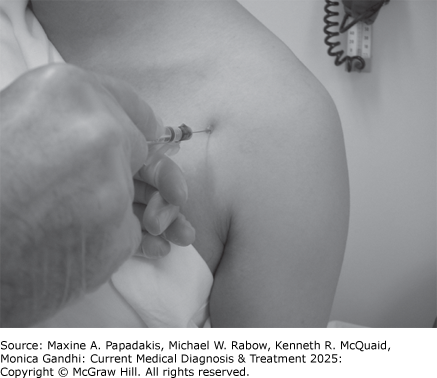

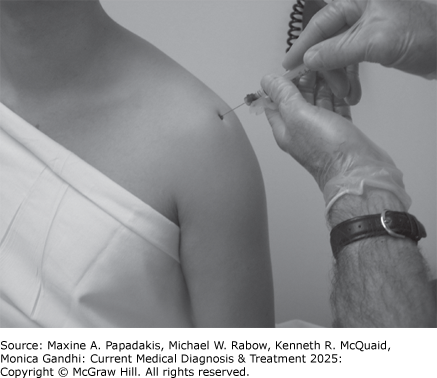

eFigure 22-2. A: Anterior View of the Shoulder

A: Anterior view of the shoulder. B: Technique for infiltration of the bicipital groove of the humerus with a glucocorticoid preparation (treatment for biceps tendinitis). C: Injection of the glenohumeral joint from the anterior position. D: Injection of the shoulder just inferior to the acromion (the preferred approach to shoulder injection). (Used, with permission, from Imboden JB et al. Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Rheumatology, 3e. McGraw-Hill, 2013.)

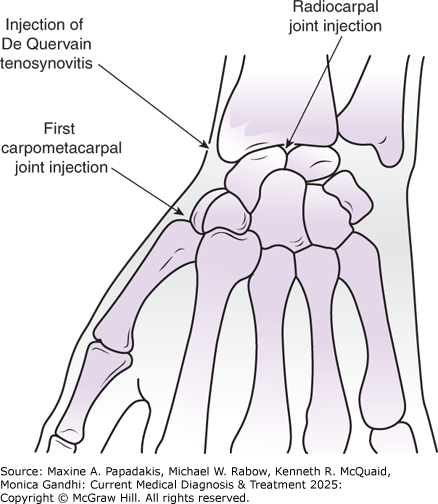

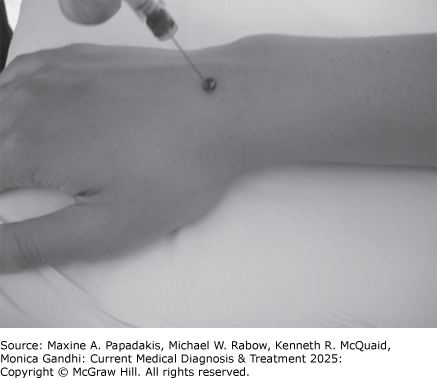

eFigure 22-3. A: Dorsum of the Left Wrist

A: Dorsum of the left wrist. B: Injection of the radiocarpal joint. (Used, with permission, from Imboden JB et al. Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Rheumatology, 3e. McGraw-Hill, 2013.)

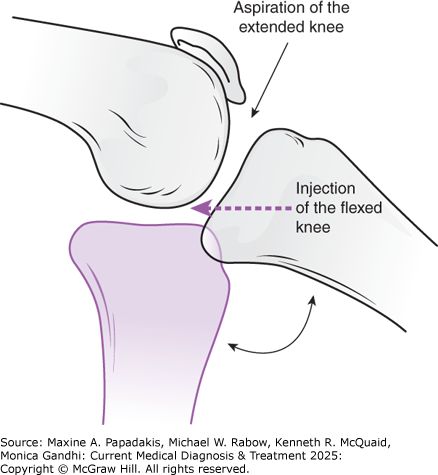

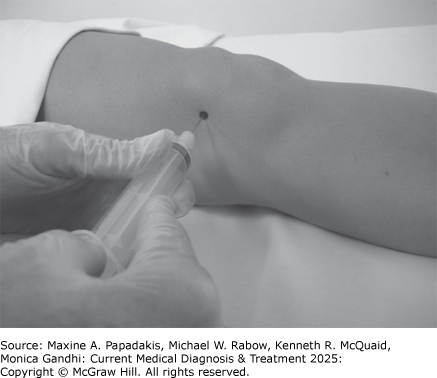

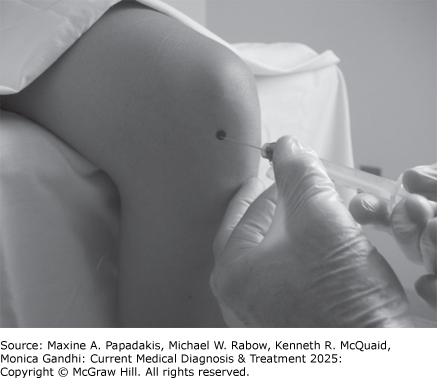

eFigure 22-4. A: Lateral View of the Knee

A: Lateral view of the knee. B: Optimal positioning of the knee for joint injection. C: Optimal positioning of the knee for joint aspiration. (Used, with permission, from Imboden JB et al. Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Rheumatology, 3e. McGraw-Hill, 2013.)

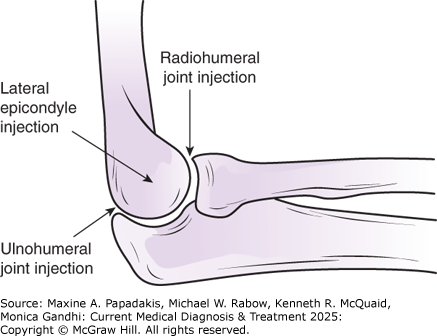

eFigure 22-5. A: Lateral View of the Elbow Flexed to 90 Degrees

A: Lateral view of the elbow flexed to 90 degrees. B: Injection of the ulnohumeral joint, into the olecranon fossa. C: Injection of the lateral epicondyle, just proximal to the radial head. (Used, with permission, from Imboden JB et al. Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Rheumatology, 3e. McGraw-Hill, 2013.)

eFigure 22-6. Injection of the Metacarpophalangeal Joint

Injection of the metacarpophalangeal joint. (Used, with permission, from Imboden JB et al. Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Rheumatology, 3e. McGraw-Hill, 2013.)

eFigure 22-7. Injection of the Trochanteric Bursa

Injection of the trochanteric bursa. (Used, with permission, from Imboden JB et al. Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Rheumatology, 3e. McGraw-Hill, 2013.)

1. Types of Studies

2. Interpretation

Synovial fluid analysis is diagnostic in infectious or microcrystalline arthritis. Although the severity of inflammation in synovial fluid can overlap among various conditions, the synovial fluid white cell count is a helpful guide to diagnosis (Table 22-3. Differential Diagnosis by Joint Fluid Groups).

Table 22-3. Differential diagnosis by joint fluid groups.| Noninflammatory (< 2000 white cells/mcL [< 2 × 109 /L]) | Inflammatory (2000-75,000 white cells/mcL [2.0-75.0 × 109 /L]) | Purulent (>100,000 white cells/mcL [>100 × 109 /L]) | Hemorrhagic |

|---|---|---|---|

Osteoarthritis Traumatic arthritis Osteonecrosis Charcot arthropathy | Rheumatoid arthritis SLE Polymyositis or dermatomyositis Systemic sclerosis Systemic vasculitides Polychondritis Gout Calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease Hydroxyapatite deposition disease Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis Ankylosing spondylitis Psoriatic arthritis Reactive arthritis IBD arthritis Hypogammaglobulinemia Sarcoidosis Rheumatic fever Indolent/low virulence infections (viral, mycobacterial, fungal, Whipple disease, Lyme disease) | Septic arthritis (bacterial) | Trauma Pigmented villonodular synovitis Tuberculosis Neoplasia Coagulopathy Charcot arthropathy |