![]()

In this chapter, you’ll learn:

Types of pain and theories that explain them

Effective ways to document pain assessment findings

History and examination techniques for the patient with pain

Psychological characteristics of pain

Specific uses of pain medications

Physical therapies used in pain management

Roles of alternative and complementary therapies in relieving pain.

Pain is a perception that is complex in nature and helps to alert the body that a potential or real tissue damage is occurring. To put it succinctly, pain is whatever the patient says it is and it occurs whenever the patient says it does. When developing a plan for pain management with the patient, it is important that the nurse not only assess the physical manifestations of pain but also the subjective reports of pain as well.

Each patient reacts to pain differently because pain thresholds and tolerances vary from person to person. Pain threshold is a physiologic attribute that denotes the intensity of the stimulus needed to sense pain. Pain tolerance is a physiologic attribute that describes the amount of stimulus (duration and intensity) that the patient can endure before stating that they are in pain.

Patients’ attitudes, beliefs, expectations of themselves, coping resources, and beliefs about the health care system affect the entire spectrum of their pain behaviors.

Behavior and emotions are influenced by the interpretation as well as the facts of an event. This partly explains why patients may differ greatly in their beliefs about pain. Beliefs about pain are very individual. Each patient has different painful experience and therefore has different expectations about pain and painful experiences. Each individual copes with pain differently throughout life. Coping with pain is specific to each patient within each event of pain.

Patients’ beliefs, judgments, and expectations about an event’s consequences—and belief in their ability to influence the outcome—can affect their ability to function. That’s because such beliefs, judgments, and expectations can influence mood directly and alter coping ability.

Patients with low back pain offer a good example. Many fail to comply with prescribed exercises. Their previous pain experience may foster a negative view of their abilities and an expectation of increased pain during exercise. These beliefs form a rationale for avoiding exercise.

Coping can be overt or covert; active or passive. Overt coping strategies include rest, drug therapy, and use of relaxation techniques. Covert coping strategies include distraction, reassuring oneself that the pain will diminish, seeking information, and solving problems.

Active coping strategies—efforts to function despite pain or to distract oneself from pain—lead to adaptive functioning. Passive coping strategies—restricting one’s activities and depending on others for help in pain control—lead to greater pain and depression.

Encouraging active pain-coping strategiesThe patient’s strategy for coping with pain may be active or passive. Active strategies include attempts to function despite pain. Passive strategies include relying on others for help in pain control.

If possible, steer the patient toward active coping strategies. A patient who uses active coping strategies tends to experience less pain and increased pain tolerance than one who uses passive strategies.

| One strategy doesn’t fit all Even so, keep in mind that one particular active coping strategy isn’t necessarily better than another. What’s more, a given strategy may be helpful in one situation or for one patient but not helpful in a different situation or for another patient. Likewise, certain strategies may help at one time but prove ineffective in other situations. |

| Out-of-control thoughts The most important feature of poor coping seems to be “catastrophizing”—thinking extremely negative thoughts about one’s plight rather than choosing poorly among active coping strategies. If the patient falls into this trap, teach them that imagining more positive outcomes may help reduce his pain. |

Pain can change the way the patient processes pain-related and other information by focusing attention on bodily signals. As these signals change, they may assume these changes mean that the underlying disease is getting worse and, as a result, may report increased pain.

In contrast, a patient who doesn’t attribute symptoms to worsening disease tends to report less pain, even if their disease actually is progressing.

Beliefs and expectations about a disease are hard to change. Patients tend to avoid experiences that might invalidate their beliefs and guide their behavior in keeping with their beliefs. Commonly, health professionals refrain from challenging patients about irrational beliefs and excessively restrictive activities. In doing so, they fail to give patients valuable corrective feedback.

Just as physical factors can affect a patient’s psychological condition, psychological factors can affect their mood, coping ability, and nociception (sensation of pain).

Cognitive interpretations and affective arousal may influence physiology by increasing autonomic sympathetic nervous system (SNS) arousal and promoting endogenous opioid (endorphin) production.

Thinking about pain and stress can increase muscle tension, especially in already painful areas. Chronic and excessive SNS arousal is a precursor to increased skeletal muscle tone. It may set the stage for hyperactive and persistent muscle contractions, which promote muscle spasms and pain.

Patients who exaggerate the significance of their problems or focus on them too closely may influence sympathetic arousal. This predisposes them to further injury and can complicate recovery in other ways.

Studies show that thoughts can influence the concentration of endorphins available to control pain. Research results indicate that:

A patient’s feelings of self-efficacy predicted their pain tolerance; those with high self-efficacy had greater levels of endorphins

Naloxone (Narcan), an opioid antagonist, blocked the pain relieving effects of cognitive coping (which demonstrates how thoughts can directly affect endorphins and that self-efficacy may influence pain perception at least partially through endogenous opioids)

Lower concentrations of endorphins were associated with learned helplessness.

Research suggests that feelings of self-efficacy can directly affect the physiology of pain. In one study, researchers provided stress management treatments to patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The autoimmune disorder, which may result from impaired suppressor T-cell functioning, causes inflammation of synovial membranes. Among the symptoms are joint pain and stiffness.

| A boost to T cells The study found that patients with increased feelings of self-efficacy had greater levels of suppressor T cells. Self-efficacy levels also related directly to the degree of pain and joint impairment the patients experienced. |

To ensure that the patient receives effective pain relief, you must conduct a thorough and accurate pain assessment. That’s a tall order because pain is so subjective.

Pain is influenced not just by physical pathology but by cultural and social factors, expectations, mood, and perceptions of control. What’s more, you and the patient may have dramatically different pain thresholds and tolerances, expectations about pain, and ways of expressing pain. Many times a person’s coping mechanism for the pain may be to try to ignore the pain. This patient may report moderate pain when asked but laugh with visitors or appear not in pain. Not all patients cry out or shed tears with pain. Some patients may be quiet and reserved wanting no visitors; others may be coping by trying to focus on something else. Even in the absence of visible injury, you as a nurse are not to question the presence of pain.

Pain is always what the person says it is. You are not the judge or jury. To keep your pain assessment on track, keep in mind the first principle of pain assessment: Pain is whatever the patient says it is, occurring whenever he says it does. The patient’s self-report of the presence and severity of pain is the most accurate, reliable means of pain assessment. If the patient reports pain, respect what he says and act promptly to assess and control it.

Pain threshold refers to the intensity of the stimulus a person needs to sense pain. Pain tolerance is the duration and intensity of pain that a person tolerates before openly expressing pain. Tolerance has a strong psychological component. Identifying pain threshold and tolerance are crucial to pain assessment and the development of a pain management plan.

Even so, remember that pain threshold and tolerance vary widely among patients. They may even fluctuate in the same patient as circumstances change.

Pain falls into three broad categories—acute pain, chronic nonmalignant pain (also called chronic persistent pain), and cancer pain.

Acute pain comes on suddenly—for instance, after trauma, surgery, or an acute disease—and lasts from a few days to a few weeks. Typically, it’s sharp, intense, and easily localized. It causes a withdrawal reflex and may trigger involuntary bodily reactions, such as sweating, fast heart and respiratory rates, and elevated blood pressure.

Acute pain: A sympathetic responseIn acute pain, certain involuntary (autonomic) reflexes may occur. Acute pain causes the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) to trigger the release of epinephrine and other catecholamines. These substances, in turn, cause physiologic reactions such as those seen in the fight-or-flight response.

| It’ll get your attention Sympathetic activation directs immediate attention to the injury site. This attention promotes reflexive withdrawal and fosters other actions that prevent further damage and enhance healing. For example, if you place your hand on a hot stove, the ANS immediately generates a reflex withdrawal that jerks your hand away and minimizes tissue damage. |

Acute pain may be constant (as in a burn), intermittent (as in a muscle strain that hurts only with activity), or both (as in an abdominal incision that hurts a little at rest and a lot with movement or coughing). It can also be prolonged or recurrent.

Acute pain may cause certain physiologic and behavioral changes that you won’t observe in a patient with chronic pain.

|

Prolonged acute pain can last days to weeks. Usually, it results from tissue injury and inflammation (as from a sprain or surgery) and subsides gradually.

At the injury site, release or synthesis of chemicals heightens sensitivity in nearby tissues. This hypersensitivity, called hyperalgesia, is normal. In fact, tenderness and tissue hypersensitivity help protect the injury site and prevent further damage.

Recurrent acute pain refers to brief painful episodes that recur at variable intervals. Examples include sickle cell vaso-occlusive crisis and migraine headache.

In migraine headache and some other recurrent conditions, pain serves no apparent useful purpose—no protective action can be taken and tissue damage can’t be prevented. However, in others, such as sickle cell disease, acute pain encourages the person to seek medical treatment.

Pain is considered chronic when it lasts beyond the normal time expected for an injury to heal or an illness to resolve. Many experts define chronic nonmalignant pain as pain lasting 6 months or longer that may continue during the patient’s lifetime. Although it sometimes begins as acute pain, more typically, it starts slowly and builds gradually. Unlike acute pain, chronic pain isn’t protective and doesn’t warn of significant tissue damage.

Chronic nonmalignant pain is unrelated to cancer. This type of pain affects more people than any other type—roughly 100 million Americans. Causes of chronic pain include nerve damage, such as in brain injury, tumor growth, or unexplained and abnormal responses to tissue injury by the central nervous system (CNS). It can cause serious disability (as in arthritis or avascular necrosis), or it may be related to poorly understood disorders such as fibromyalgia and complex regional pain syndrome. Neuropathic pain is one type of chronic pain.

Understanding neuropathic painCommonly described as tingling, burning, or shooting, neuropathic pain is a puzzling type of chronic pain generated by the nerves. It commonly has no apparent cause and responds poorly to standard pain treatment.

We don’t know the precise mechanism of neuropathic pain. Possibly, the peripheral nervous system has experienced damage that injures sensory neurons, causing continuous depolarization and pain transmission. Alternatively, it could result from repeated noxious stimuli that cause hypersensitivity and excitement in the spinal cord that results in chronic neuropathy in which a normally harmless stimuli causes pain.

| The limb is gone, but the pain remains Phantom pain syndrome is one example of neuropathic pain. This condition occurs when an arm or a leg has been removed but the brain still gets pain messages from the nerves that originally carried the limb’s impulses. The nerves seem to misfire, causing pain. |

| Types of neuropathic pain Neuropathic pain can involve peripheral or central pain. Peripheral pain can occur as:

Central neuropathic pain also comes in two varieties:

|

Chronic pain may be severe enough to limit a patient’s ability and desire to participate in career, family life, and even activities of daily living. If it’s severe or intractable, the patient may experience decreased function, pain behaviors, depression, opioid dependence, “doctor shopping,” and suicide.

You may find pain assessment especially difficult in a patient with chronic pain. Over time, the autonomic nervous system (ANS) adapts to pain, so the patient may lack typical autonomic responses, such as dilated pupils, increased blood pressure, and fast heart and respiratory rates. Also, their facial expression may not suggest pain. They may sleep periodically and shift their attention away from the pain. Regardless, don’t let the lack of outward signs lead you to conclude that they aren’t in pain.

Pain from cancer is more than just pain. You must assess for suffering and quality of life in addition to presence of pain. Cancer pain is a complex problem. It may result from the disease itself or from treatment. About 70% to 90% of patients with advanced cancer experience pain. Although cancer pain can be treated with oral medications, only one third of patients with cancer pain achieve satisfactory relief.

Sometimes, pain results from the pressure of a tumor impinging on organs, bones, nerves, or blood vessels. In other cases, limitations in activities of daily living may lead to muscle aches.

These cancer treatments may cause pain:

Chemotherapy, radiation, or drugs used to offset the impact of these therapies on blood counts and infection risk (such as mouth sores; peripheral neuropathy; and abdominal, bone, or joint pain from chemotherapy agents)

Surgery

Biopsies

Blood withdrawal

Lumbar punctures.

In 2000, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) issued new standards for pain assessment, management, and documentation. These standards require health care workers to ask patients about pain when they’re admitted to a JCAHO-accredited facility. Any patient who reports pain must be assessed further by licensed personnel. Facility policies must identify a standard pain screening tool to be used for all patients able to use it.

If you work in a JCAHO-accredited facility, check policies and procedures for information on which screening tool to use, how often to assess pain, and which pain level warrants further assessment and action. (In many facilities, this level is 4 or higher on a scale of 0 to 10.)

Pain is commonly called the fifth vital sign because pain assessment scores must be monitored and recorded regularly—and at least as vigilantly as you monitor and record vital signs. To meet JCAHO standards, you must record pain assessment data in a way that promotes reassessment.

JCAHO standards also mandate that health care facilities plan and support activities and resources that assure pain recognition and use of appropriate interventions. These activities include:

Initial pain assessment

Regular reassessment of pain

Education of health care workers about pain assessment and management

Development of quality improvement plans that address pain assessment and reassessment.

When a patient is admitted, ask them if they currently are in pain or have ongoing problems with pain. If they have ongoing pain, find out if they have an effective treatment plan. If so, continue with this plan if possible. If they do not have such a plan, use an assessment tool, such as a pain rating scale, to further assess the pain.

Pain rating scales quantify pain intensity—one of pain’s most subjective aspects. These scales offer several advantages over semistructured and unstructured patient interviews:

They’re easier to administer.

They take less time.

They can uncover concerns that warrant a more thorough investigation.

When used before and after a pain control intervention, they can help determine if the intervention was effective.

Pain rating scales come in many varieties. When choosing an appropriate scale for your patient, consider his visual acuity, age, reading ability, and level of understanding.

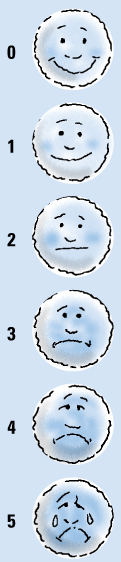

You can evaluate pain in a nonverbal manner for pediatric patients age 3 and older or for adult patients with language difficulties. One common pain rating scale consists of six faces with expressions ranging from happy and smiling to sad and teary.

To use a pain intensity rating scale, tell the patient that each face represents a person with progressively worse pain. Ask them to choose the face that best represents how they feel. Explain that although the last face has tears, they can choose this face even if they are not crying.

A pediatric patient or an adult patient with language difficulties may not be able to express the pain they are feeling. In such instances, use the pain intensity scale below. Ask your patient to choose the face that best represents the severity of the pain, on a scale from 0 to 5.

The visual analog scale is a horizontal line, 10 cm (3⅝″) long, with word descriptors at each end: “no pain” on one end and “pain as bad as it can be” on the other. The scale may also be used vertically.

Ask the patient to place a mark along the line to indicate the intensity of the pain. Then measure the line in millimeters up to his mark. This measurement represents the patient’s pain rating. Be aware that this scale may be too abstract for some patients to use.

To use the visual analog scale, ask the patient to place a line across the scale to indicate their current level of pain. The pain rating is determined by measuring the distance, in millimeters, from “no pain” to their marking.

The numerical rating scale is perhaps the most commonly used pain rating scale. Simply ask the patient to rate their pain on a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 representing no pain and 10 representing the worst pain imaginable. Instead of giving a verbal rating, the patient can use a horizontal or vertical line consisting of descriptive words and numbers.

Although most patients find the numerical rating scale quick and easy to use, it may be too abstract for some patients. The numerical rating scale may also be frustrating to the patient who has pain and hurts but pain is not unbearable. Many patients have the belief that in order to request pain medication, they have to be suffering. It is up to the nurse to offer pain medication on a regular basis, regardless of the number. The number should be used to assess pain management and not to judge whether a person needs to be medicated.

Using the numerical rating scaleA numerical rating scale (NRS) can help the patient quantify their pain. Have them choose a number from 0 (indicating no pain) to 10 (indicating the worst pain imaginable) to reflect their current pain level. The patient can either circle the number on the scale itself or verbally state the number that best describes the pain.

| Not as simple as it sounds To be on the safe side, don’t assume that your patient knows how to use the scale. Provide teaching and then verify that they understand what you’ve taught. Be sure to document your teaching and your method of evaluating their understanding. |

| Work toward a comfort goal Help the patient establish a comfort goal—a numerical pain level that will enable them to perform self-care activities, such as ambulation, coughing, and deep breathing. Usually, a level of 3 or less on a 0-to-10 scale is an adequate comfort level. If the patient chooses a comfort goal of 4 or higher, teach them that unrelieved pain can damage their health. Discuss concerns they may have about using analgesics and clear up misconceptions such as those related to addiction. |

| When to evaluate the pain management plan If the patient rates the pain as 10, he’s experiencing severe pain—a sign that the pain management plan is ineffective. Consult with the doctor about increasing the analgesic dose or adding another analgesic. |

| When to use a vertical scale instead Like some children, many adults who speak languages that are read from right to left (or vertically) may have trouble with the NRS because it’s horizontal. They may find a vertical scale easier to use. When using a vertical scale, place 0 at the bottom of the scale and 10 at the top. |

With the verbal descriptor scale, the patient chooses a description of their pain from a list of adjectives, such as “none,” “annoying,” “uncomfortable,” “dreadful,” “horrible,” and “agonizing.”

Like the numerical rating scale, the verbal descriptor scale is quick and easy, but it does have drawbacks:

It limits the patient’s choices.

Patients tend to choose moderate rather than extreme descriptors.

Some patients may not understand all the adjectives.

Overall pain assessment tools evaluate pain in multiple dimensions, providing a wider range of information. These tools are time-consuming and may be more practical for outpatient use. Still, you might want to use one for a hospitalized patient with hard-to-control chronic pain. Be sure to document the patient’s pain according to your facility policy.

Be sure to document baseline pain assessment findings so that you and other team members can use them for later comparison. You may want to use a standardized documentation form such as the pain assessment guide mentioned earlier.

If the patient has unrelieved pain, you’ll need to conduct frequent assessments. To make pain assessment findings more visible, consider using a graphic sheet that lets you document pain severity next to vital signs.

| Pain assessment flow sheet A pain assessment flow sheet provides a convenient way to track the patient’s pain level and response to interventions over time. On a typical flow sheet, you record information about the patient’s pain severity rating, therapeutic interventions, effects of each intervention, and adverse effects of treatments (such as nausea and sedation). A pain assessment flow sheet is useful inside and outside the hospital. After discharge, the patient and his family may want to use the flow sheet along with a pain diary in which the patient records their activities, pain intensity, and pain interventions. The diary can reveal the extent to which pain management measures and activities affect the pain level. |

| Analgesic infusion flow sheet If the patient is receiving an analgesic infusion, you may use an analgesic infusion flow sheet to speed documentation and track their progress. Information to record on the flow sheet includes the:

|

| Oral medication flow sheet An oral medication flow sheet can be a valuable tool for:

|

Accurate pain assessment yields information that serves as the basis for an individualized pain management plan. For a patient with acute pain, a brief assessment may be adequate to formulate an appropriate plan.

However, a patient with chronic pain may require a thorough assessment that evaluates physical and psychosocial factors. Still, even the best history and examination techniques may not produce the definitive findings needed to make a precise diagnosis and clearly identify the origin of chronic pain. Usually, history and physical findings help the doctor interpret the results of diagnostic tests.

Assessment begins with the patient interview. If they have acute pain from a traumatic injury, the interview may last for mere seconds. If they have chronic pain, it may be lengthy.

When interviewing a patient with chronic pain, try to elicit information that sheds light on his thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and physiologic responses to pain. Also find out about the environmental stimuli that can alter his response to pain. With a patient who is experiencing chronic pain, their lifestyle most likely has been affected by the pain. Find out if there are any activities that the person used to enjoy doing that are now impossible because of the pain.

During the interview, assess the cognitive, affective, and behavioral components of the patient’s pain experience. Doing so can help you later when working with the patient to develop pain management goals. Also ask questions to determine how the pain affects their mental state, relationships, and work performance.

Question the patient about these characteristics of his pain:

onset and duration—when did the pain begin? Did it come on suddenly or gradually? Is it intermittent or continuous? How often does it occur? How long does it last? Is it prolonged or recurrent?

location—ask the patient to point to the painful parts of the body or to mark these areas on a diagram. Be sure to assess each pain site separately.

intensity—using a pain rating scale, ask the patient to quantify the intensity of the pain at its worst and at its best.

quality—ask the patient what the pain feels like, in their own words. Does it have a burning quality? Is it knifelike? Do they feel pressure? Throbbing? Soreness?

relieving factors—does anything help relieve the pain, such as a certain position or heat or cold applications? Besides helping to pinpoint the cause of the pain, the answers may aid in developing a pain management plan.

aggravating factors—what seems to trigger the pain? What makes it worse? Does it get worse when the patient moves or changes position?

You may find the provoke, quality, radiate, severity, and time (PQRST) technique valuable when assessing pain. Each letter stands for a crucial aspect of pain to explore.

The patient’s medical history may offer clues to the source of pain or a condition that may exacerbate it. Ask them to list all of their past medical conditions, even those that have been resolved. Also question them about previous surgeries.

Explore the patient’s experiences with pain. If they experienced significant pain in the past, they may have anticipatory fear of future pain—especially if they received inadequate pain relief.

Ask the patient which previous treatments—pharmacologic and otherwise—they tried, and find out which treatments helped and which didn’t. Keep in mind that nonpharmacologic treatments include physical and occupational therapy, acupuncture, hypnosis, meditation, biofeedback, heat and cold therapy, transcutaneous nerve stimulation, and psychological counseling.

Obtain a complete list of the patient’s medications. (Many medications can alter the effectiveness of analgesics.) Besides prescribed drugs, ask if they take over-the-counter preparations, vitamins, nutritional supplements, or herbal or homemade remedies. Record the name, dose, frequency, administration route, and adverse effects of each agent used. Also ask about drug allergies.

Find out if the patient currently takes or has previously taken medications to control pain and whether these were effective. If they currently receive analgesics, have them describe exactly how they take them. If they haven’t been taking them according to instructions, they may need additional teaching on proper administration. If a particular analgesic agent or regimen didn’t work for them in the past, you may be able to teach them how to use it effectively by tailoring the dosage or regimen to their needs.

Ask the patient if they are satisfied with the level of pain relief the current medications bring. Find out how long these drugs take to work and whether the pain returns before the next dose is due.

Question the patient about adverse effects, such as nausea, constipation, and drowsiness. If they are taking opioids for pain relief, note any worries they have about becoming drug dependent. Listen carefully for concerns they may have about any medication.

Thorough pain assessment includes a social history. Many social factors can influence the patient’s perception and reports of pain and vice versa. This information also helps guide interventions.

Find out how the patient feels about himself, his place in society, and their relationships with others. Ask about marital status; occupation; support systems; financial status; hobbies; exercise and sleep patterns; responsibilities; and religious, spiritual, and cultural beliefs. Determine patterns of alcohol use, smoking, and illicit drug use.

Chronic pain can have wide-ranging effects on a person’s life. If your patient has chronic pain, explore the impact it has on moods, emotions, expectations, coping efforts, and resources. Also ask how family responds to their condition.

To provide culturally sensitive care, you must determine the meaning of pain for each patient—particularly in the context of culture and religion. Determine how cultural background and religious beliefs may affect pain experience. In some cultures, pain is openly expressed. Other cultures value stoicism and denial of pain. A patient who comes from a stoic culture may lead you to believe that they are not in pain.

Be sure not to stereotype your patient. Keep in mind that, within each culture, the response to pain may vary from person to person. Also recognize your own cultural values and biases. Otherwise, you may end up evaluating the patient’s response to pain according to your own beliefs instead of theirs.

Start the physical examination by observing the patient. They may display a broad range of behaviors to convey pain, distress, and suffering. Some behaviors are controllable. Others, such as heavy perspiring or pupil dilation, are involuntary.

As you observe the patient before or during the physical examination, note and document behaviors. Use your observations to help quantify the pain.

| Pain behavior checklist A pain behavior is something a patient uses to communicate pain, distress, or suffering. Place a check in the box next to each behavior you observe or infer while talking to your patient.

|

These overt behaviors may indicate that the patient is experiencing pain:

Verbal reports of pain

Vocalizations, such as sighs and moans

Altered motor activities (frequent position changes, guarded positioning, slow movements, and rigidity)

Limping

Grimacing and other expressions

Functional limitations, including reclining for long periods

Actions to reduce pain such as taking medication.

Next, measure the patient’s blood pressure, heart and respiratory rates, and pupil size. Acute pain may raise blood pressure, speed the heart and respiratory rates, and dilate pupils.

Remember, however, that these autonomic responses may be absent in a patient with chronic pain because the body gradually adapts to pain. Don’t assume lack of autonomic responses means lack of pain.

To complete the examination, use a systematic technique to perform palpation, percussion, and auscultation. If the patient is in severe pain, you may need to shorten the examination, completing it later when his pain has decreased.

If diagnostic tests don’t find a physical basis for the patient’s pain, some health care providers may label the pain psychogenic. Psychogenic pain refers to pain associated with psychological factors. A patient with psychogenic pain may have organic pathology, or a psychological disorder may be the predominant influence on pain intensity.

Common psychogenic pain syndromes include chronic headache, muscle pain, back pain, and stomach or pelvic pain of unknown cause.

Keep in mind that psychogenic pain is real pain and doesn’t mean the patient is malingering. Remember, too, that although pain can cause emotional distress, such distress isn’t necessarily the cause of the psychogenic pain.

If objective physical findings do not substantiate the patient’s complaints or if their pain severity rating seems excessive in light of physical findings, consider referring them to a psychologist or psychiatrist who specializes in evaluating chronic pain.

Many patients with chronic pain go from doctor to doctor and undergo exhausting procedures seeking a diagnosis and effective treatment. If their pain doesn’t respond to treatment, they may feel health care providers, employers, and family are blaming—or doubting—them. In time, pain may become the central focus of their lives. They may withdraw from society, lose their jobs, and alienate family and friends.

Not surprisingly, many patients with chronic pain feel anxious, depressed, demoralized, helpless, hopeless, frustrated, angry, and isolated. They may suffer from insomnia, disruption of usual activities, drug abuse and dependence, anger, and violence. Some even attempt suicide.

For health care providers, assessment and management of patients with pain—especially chronic pain—can be equally frustrating. However, that doesn’t mean you should lose heart or blame the patient. Through careful assessment and regular reevaluation, you can increase the odds for successful pain management—even in patients with seemingly intractable or chronic pain.

When caring for a patient experiencing pain, you have three overall goals:

Reduce pain intensity

Reduce pain intensity Improve the patient’s ability to function

Improve the patient’s ability to function Improve the patient’s quality of life.

Improve the patient’s quality of life.To accomplish these goals, you must work with the patient to agree on goals that are mutually desirable, realistic, measurable, and achievable. In addition, you’ll need to focus on the nociceptive and emotional aspects of pain. A patient responds to a painful physical condition based, in part, on their subjective interpretation of illness and symptoms. The patient’s beliefs about the meaning of pain and ability to function despite discomfort are important aspects of coping ability.

Maladaptive responses to pain are more likely in a patient who believes that:

He has a serious debilitating condition

Disability is a necessary aspect of pain

Activity is dangerous

Pain is an acceptable reason to reduce one’s responsibilities.

Many factors can promote or disrupt a patient’s sense of control over the pain experience. They include:

Personal beliefs and expectations about pain

Coping ability

Social supports

Specific disorder that’s causing the pain

Response of employers.

These factors also influence a patient’s investment in treatment, acceptance of responsibility, perceptions of disability, adherence to treatment, and support from significant others. To start the patient on the road to successful pain management, consider physical, psychosocial, and behavioral factors—and the changes that occur in these relationships over time.

An interdisciplinary team approach promotes effective pain management. Team members typically include a doctor, a nurse, a pharmacist, a social worker, a spiritual advisor, a psychologist, physical and occupational therapists, an anesthesiologist or a certified registered nurse anesthetist, a pain management specialist and, of course, the patient and his family.

In addition to the three overall goals of treating pain, consider ways to treat specific types of pain.

The cause of acute pain can be diagnosed and treated, and the pain resolves when the cause is treated or analgesics are given. Drug regimens and invasive procedures that aren’t reasonable for extended periods can be used more freely in acute pain. With acute pain, it is important to stay ahead of the pain. Many physicians will order pain medication around the clock to be given to the patient.

Medical treatment for chronic nonmalignant pain must be based on the patient’s long-term benefit, not just the current complaint of pain. Drug therapy and surgery, which typically provide only partial and temporary relief, should be individualized.

Drug treatment alone almost never effectively relieves chronic nonmalignant pain. The patient must receive a combination of treatments. These may include drugs, nondrug therapies, temporary or permanent invasive therapies (such as nerve blocks or surgery), cognitive-behavioral therapy, alternative and complementary therapies, and self-management techniques.

Even with medical management, however, chronic nonmalignant pain can be lifelong. Therefore, treatments that carry significant risks or aren’t likely to prove effective over the long-term may be inappropriate.

In many cases, treatment of chronic nonmalignant pain must focus on rehabilitation rather than a cure. Rehabilitation aims to:

Maximize physical and psychological functional abilities

Minimize pain experienced during rehabilitation and for the rest of the patient’s life

Teach the patient how to manage residual pain and handle pain exacerbation caused by increased activity or unexplained reasons.

Whether pain results from cancer or its treatment, it may cause the patient to lose hope—especially if they think the pain means illness is progressing. They are then likely to suffer additional feelings of helplessness, anxiety, and depression.

However, most types of cancer pain can be managed effectively, diminishing physical and mental suffering.

Unfortunately, cancer pain commonly goes undertreated because of:

Inadequate knowledge of—or attention to—pain control by health care professionals

Failure of health care professionals to properly assess pain

Reluctance of patients to report their pain

Reluctance of patients and doctors to use morphine and other opioids due to fear of addiction.

Undertreated cancer pain diminishes the patient’s activity level, appetite, and sleep. It may prevent the patient from working productively, enjoying leisure activities, or participating in family or social situations.

The success of a pain management plan hinges on having the patient choose an appropriate goal—a pain intensity rating that will reduce his discomfort to a tolerable level and let him engage comfortably in self-care activities. Team members should work together to choose a rating scale for measuring the patient’s pain intensity and to develop appropriate pain management goals.

Thorough documentation and pain assessment tools communicate vital patient information to all team members. If the patient has chronic pain, periodic team meetings also may be crucial.

Pain management can be pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic. Pharmacologic pain management includes nonopioid analgesics, opioids, and adjuvant analgesics. In addition, nonpharmacologic pain management can include alternative and complementary therapies.

Nonopioid (nonnarcotic) analgesics are used to treat pain that’s nociceptive (caused by stimulation of injury-sensing receptors) or neuropathic (arising from nerves). These drugs are particularly effective against the somatic component of nociceptive pain such as joint and muscle pain. In addition to controlling pain, nonopioid analgesics reduce inflammation and fever.

Drug types in this category include:

Acetaminophen (Tylenol)

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (Advil)

Salicylates such as aspirin.

When used alone, acetaminophen and NSAIDs provide relief from mild pain. NSAIDs can also relieve moderate pain; in high doses, they may help relieve severe pain. Given in combination with opioids, nonopioid analgesics provide additional analgesia, allowing a lower opioid dose and, thus, a lower risk of adverse effects.

Opioids (narcotics) include derivatives of the opium (poppy) plant and synthetic drugs that imitate natural opioids. Unlike NSAIDs, which act peripherally, opioids produce their primary effects in the CNS. Opioids include opioid agonists, opioid antagonists, and mixed agonist-antagonists.

Opioid agonists are used to treat moderate to severe pain without causing loss of consciousness. Opioid agonists include:

Codeine

Fentanyl (Duragesic)

Hydromorphone (Dilaudid)

Methadone (Dolophine)

Morphine (Avinza) (including sustained-release tablets and intensified oral solution)

Oxycodone (Percolone).

Opioid antagonists aren’t pain medications but block the effects of opioid agonists. They’re used to reverse adverse drug reactions, such as respiratory and CNS depression produced by opioid agonists. Unfortunately, by reversing analgesic effects, they may cause the patient’s pain to recur.

Opioid antagonists attach to opiate receptors but don’t stimulate them. As a result, they prevent other opioids, enkephalins, and endorphins from producing their effects. Opioid antagonists include naloxone (Narcan) and naltrexone (Depade).

As their name implies, mixed opioid agonist-antagonists have agonist and antagonist properties. The agonist component relieves pain while the antagonist component reduces the risk of toxicity and drug dependence. These agents also decrease the risk of respiratory depression and drug abuse. These agents include:

Buprenorphine (Buprenex)

Butorphanol (Stadol)

Nalbuphine (Nubain)

Pentazocine hydrochloride (Talwin) (combined with pentazocine lactate, naloxone, aspirin, or acetaminophen).

Originally, mixed agonist-antagonists seemed to have less addiction potential than pure opioid agonists as well as a lower risk of drug dependence. However, butorphanol and pentazocine reportedly have caused dependence.

Adjuvant analgesics are drugs that have other primary indications but are used as analgesics in some circumstances. Adjuvants may be given in combination with opioids or used alone to treat chronic pain. Patients receiving adjuvant analgesics should be reevaluated periodically to monitor their pain level and check for adverse reactions.

Drugs used as adjuvant analgesics include certain anticonvulsants, local and topical anesthetics, muscle relaxants, tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine agonists, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, ergotamine alkaloids, benzodiazepines, psych stimulants, cholinergic blockers, and corticosteroids.

Managing pain doesn’t necessarily involve capsules, syringes, I.V. lines, or medication pumps. Many nonpharmacologic therapies are available, too—and they’re gaining popularity among the general public and health care professionals alike.

What accounts for this trend? For one thing, many people are concerned about the overuse of drugs for conventional pain management. For another, some people simply prefer to self-manage their health problems.

Collectively speaking, nonpharmacologic approaches offer something for nearly everyone. They range from the relatively conventional (whirlpools, hot packs) to the electrifying (vibration, electrical nerve stimulation), sensual (aromatherapy, massage), serene (meditation, yoga), and high-tech (biofeedback).

These therapies fall into three main categories:

Physical therapies

Physical therapies Alternative and complementary therapies

Alternative and complementary therapies Cognitive and behavioral therapies.

Cognitive and behavioral therapies.Many of these therapies can be used alone or combined with drug therapy. A combination approach may improve pain relief by enhancing drug effects and allowing lower dosages.

Nonpharmacologic approaches have other benefits in addition to pain management. For example, they help reduce stress, improve mood, promote sleep, and give the patient a sense of control over pain.

By understanding how these techniques work and how best to use them, you can provide additional options for patients who experience pain. Although the techniques discussed in this chapter can be effective for a wide range of patients, they’re best administered, prescribed, or taught by licensed practitioners or experienced, credentialed lay people. A few require a doctor’s order.

Physical therapies use physical agents and methods to aid rehabilitation and restore normal functioning after an illness or injury. These therapies are relatively cheap and easy to use. With appropriate teaching, patients and their families can use them on their own, which helps them participate in pain management.

Physical therapies include:

Hydrotherapy

Thermotherapy

Cryotherapy

Vibration

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS).

In addition to easing pain, physical therapies reduce inflammation, ease muscle spasms, and promote relaxation. The goals of physical therapies are to:

Promote health

Prevent physical disability

Rehabilitate patients disabled by pain, disease, or injury.

Hydrotherapy uses water to treat pain and disease. Sometimes called the ultimate natural pain reliever, water comforts and soothes while providing support and buoyancy. Depending on the patient’s problem, the water can be hot or cold, and liquid, solid (ice), or steam. It can be applied externally or internally.

Most commonly prescribed for burns, hydrotherapy relaxes muscles, raises or lowers tissue temperature (depending on water temperature), and eases joint stiffness (as in rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis). In pain management, hydrotherapy is most commonly used to treat acute pain—for instance, from muscle sprains or strains.

Whirlpool baths—bathtubs with jets that force water to circulate—aid in rehabilitating injured muscles and joints. Depending on the desired effect, the water can be hot or cold. The water jets act to massage soothing muscles.

Pools that ease painHydrotherapy commonly takes the form of a whirlpool bath, which uses water jets to help ease pain.

Pool tips

This illustration shows a patient whose leg injury is being treated in a whirlpool.

|

Whirlpools and certain other hydrotherapy treatments can be done at home. However, the more intensive forms are best done in a supervised clinical setting where the treatment and the patient’s response can be monitored.

Other forms of hydrotherapy include a neutral bath and a sitz bath. In a neutral bath, the patient is immersed fully (up to the neck) in water that’s near body temperature. This soothing bath calms the nervous system. In a sitz bath, the pelvic area is immersed in a tub of water to relieve perianal pain, swelling, or discomfort; boost circulation; and reduce inflammation.

Hydrotherapy’s pain-relieving properties are related to the physics and mechanics of water and its effect on the human body. When a body is immersed in water, the resulting weightlessness reduces stress on joints, muscles, and other connective tissues. This buoyancy may relieve some types of pain instantly.

Hot water hydrotherapy eases pain through a sequence of events triggered by increased skin temperature. As skin temperature rises, blood vessels widen and skin circulation increases. As resistance to blood flow through veins and capillaries drops, blood pressure decreases. The heart rate then rises to maintain blood pressure. The result is a significant drop in pain and greater comfort.

As with any treatment, be aware of these potential hazards of hydrotherapy:

Hydrotherapy may cause burns, falls, or light-headedness.

Stop the treatment session if the patient feels light-headed, dizzy, or faint.

Don’t keep the patient in a heated whirlpool for more than 20 minutes.

Instruct the patient to wipe their face frequently with a cool washcloth so they won’t get overheated.

Know that hydrotherapy isn’t recommended for pregnant women; children; elderly patients; or patients with diabetes, hypertension, hypotension, or multiple sclerosis.

Thermotherapy refers to application of dry or moist heat to decrease pain, relieve stiff joints, ease muscle aches and spasms, improve circulation, and increase the pain threshold. Dry heat can be applied with a K-pad or an electric heating pad. Moist heat can be applied with a hot pack, a warm compress, or a special heating pad. Dry and moist heat involves conductive heating—heat transfer that occurs when the skin directly contacts a warm object.

Thermotherapy is used to treat pain caused by:

Headache

Muscle aches and spasms

Earache

Menstrual cramps

Temporomandibular joint disease

Fibromyalgia (syndrome of chronic pain in the muscles and soft tissues surrounding joints).

Thermotherapy enhances blood flow, increases tissue metabolism, and decreases vasomotor tone. It produces analgesia by suppressing free nerve endings. It also may reduce the perception of pain in the cerebral cortex.

Regional heating—heat therapy of selected body areas—can bring immediate temporary pain relief. This method may have a systemic effect, too, resulting from autonomic reflex responses to localized heat application. The reflex-mediated responses may raise body temperature, enhance blood flow, and cause other physiologic changes in areas distant from the heat application site.

| Thermo thoughts Before administering thermotherapy, take these considerations into account:

|

Cryotherapy involves applying cold to a specific body area. In addition to reducing fever, this technique can provide immediate pain relief and help reduce or prevent edema and swelling.

Cryotherapy methods include cold packs and ice bags for pain relief measures. These measures should only be left on a patient for 20 minutes. Ice is used in acute injury along with rest, compression, and elevation.

In another cryotherapy technique, known as contrast therapy, cold and heat application are applied alternately during the same session. Contrast therapy may benefit patients with rheumatoid arthritis and certain other conditions.

Typically, the session begins by immersing the patient’s feet and hands in warm water for 10 minutes. Next come four cycles of cold soaks (each lasting 1 to 4 minutes) alternating with warm soaks (each lasting 4 to 6 minutes).

Cryotherapy is commonly used for acute pain—especially when caused by a sports injury (such as a muscle sprain). It may also be indicated for pain resulting from:

Acute trauma

Joint disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis

Headache such as migraine

Muscle aches and spasms

Incisions

Surgery.

Cryotherapy constricts blood vessels at the injury site, reducing blood flow to the site. This, in turn, thickens the blood, resulting in decreased bleeding and increased blood clotting.

RICE Therapy

|

Cold application also slows edema development, prevents further tissue damage, and minimizes bruising.

Cryotherapy also decreases sensitivity to pain by cooling nerve endings. It eases muscle spasms by cooling muscle spindles—the part of the muscle tissue responsible for the stretch reflex. Contrast therapy is thought to stimulate endocrine function, reduce inflammation, decrease congestion, and improve organ function.

Applying cold to a muscle sprainCryotherapy helps reduce pain and edema when used during the first 24 to 72 hours after an injury. For best results, follow these guidelines.

Method and materials

|

The old switcheroo

|

Wise words

|

When administering cryotherapy, remember these points:

As appropriate, encourage your patient to try cold application. Many patients aren’t aware that cold relieves pain.

Before applying cold, assess the pain or injury site and the patient’s pain level. Evaluate him for impaired circulation (such as from Raynaud’s disease), inability to sense temperature (as from neuropathy), extreme skin sensitivity, and inability to report the response to treatment (for instance, a young child or a confused elderly patient).

If the patient has a cognitive impairment, measure the temperature of the cooling agent. It should be no colder than 59° F (15° C).

When administering moist cold, keep in mind that moisture intensifies cold.

Wrap cold packs so they don’t directly contact the patient’s skin. Keep them at a comfortable temperature.

Stop the treatment if the patient’s skin becomes numb.

Use caution when applying ice to the elbow, wrist, or outer part of the knee. These sites are more susceptible to cold-induced nerve injury.

Be aware that refreezable gel packs and chemical packs may be colder than ice. Also, they may leak.

Regularly assess the patient for adverse effects such as skin irritation, joint stiffness, numbness, frostbite, and nerve injury.

Don’t apply cold to areas that have poor circulation or have received radiation.

Vibration therapy eases pain by inducing numbness in the treated area. This technique, which works like an electric massage, may be effective in such disorders as:

Muscle aches

Headache

Chronic nonmalignant pain

Cancer pain

Fractures

Neuropathic pain.

Hospitalized patients need a doctor’s order to use a vibrating device. Outpatients may choose from various devices available without a prescription.

A vibrating device can be stationary or handheld. Stationary devices range from vibrating cushions to full beds and recliners. The patient lies or sits on the device and receives the treatment passively.

With a handheld vibrator, the patient or a caregiver moves the device over the painful area. Some handheld vibrators are battery-operated; others plug into a wall outlet.

Handheld vibrators come in many shapes and sizes. Some are relatively heavy and may be hard for frail or arthritic patients to use.

Remember these points when administering vibration therapy:

Before using vibration therapy, teach your patient about this method, including how it works and when it should and shouldn’t be used.

Tell the patient they may feel a warm sensation initially.

Apply the vibrator to an area above or below the pain site.

For more effective pain relief, use the highest vibration speed the patient can tolerate.

Apply the vibrating device for 1 to 15 minutes at a time, two to four times daily, or as ordered.

Determine the length of treatment needed to achieve adequate pain relief. Continue to assess the patient’s response to treatment.

Stop the treatment if the patient experiences discomfort, pain, or excessive skin redness or irritation.

Don’t use vibration therapy if the patient has thrombophlebitis or bruises easily.

Don’t apply the vibrator over burns, cuts, or incision sites.

If the patient will self-administer this therapy, provide appropriate teaching. Advise them to assess their pain level before the session, immediately afterward, and at a later time to assess how long pain relief lasts. Doing so helps determine the optimal length of treatment. (Usually, the longer the session, the longer the duration of pain relief.)

In TENS therapy, a portable, battery-powered device transmits painless alternating electric current to peripheral nerves or directly to a painful area. Used postoperatively and for patients with chronic pain, TENS reduces the need for analgesic drugs and helps the patient resume normal activities. TENS therapy must be prescribed by a doctor.

The patient usually wears the TENS unit on a belt. Units have several channels and lead placements. The settings allow adjustment of wave frequency, duration, and intensity.

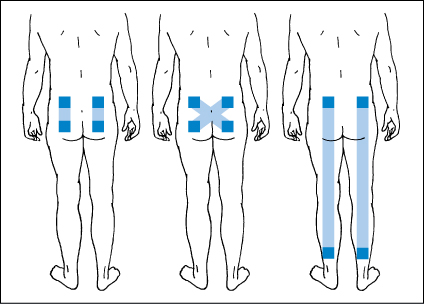

Positioning TENS electrodesIn transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), electrodes placed around peripheral nerves or incision sites transmit mild electrical impulses, which presumably block pain messages.

| Perfect placement Electrode placement usually varies, even for patients with similar complaints. Electrodes can be placed in several ways:

These illustrations show combinations of electrode placement (dark squares) and areas of nerve stimulation (shaded strips) for low back and leg pain. |

Placement tips

|

Typically, a course of TENS therapy lasts 3 to 5 days. Some conditions (such as phantom limb pain) may require continuous simulation. Others, such as a painful arthritic joint, call for shorter treatment periods—perhaps 3 to 4 hours.

TENS can provide temporary relief of acute pain (such as postoperative pain) and ongoing relief of chronic pain (such as in sciatica). Specific pain problems that have responded to TENS include:

Chronic nonmalignant pain

Cancer pain

Bone fracture pain

Low back pain

Sports injuries

Myofascial pain

Neurogenic pain (as in neuralgia and neuropathy)

Phantom limb pain

Arthritis

Menstrual pain.

Although TENS has existed for about 30 years, experts still aren’t sure exactly how it relieves pain. Some believe that it works according to the gate-control theory, which proposes that painful impulses pass through a “gate” in the brain. According to this theory, TENS alters the patient’s perception of pain by closing the gate to painful stimuli.

Consider these points when administering TENS therapy:

To ensure that your patient is a willing and active participant in TENS therapy, provide complete instructions on using and caring for the TENS unit as well as expected results of treatment.

Before TENS therapy begins, assess the patient’s pain level and evaluate for skin irritation at the sites where electrodes will be placed.

Be aware that the safety of TENS during pregnancy hasn’t been established.

Don’t use TENS if the patient has undiagnosed pain, uses a pacemaker, or has a history of heart arrhythmias.

Don’t apply a TENS unit over the carotid sinus, an open wound, or anesthetized skin.

Don’t place the unit on the head or neck of a patient who has a vascular disorder or seizure disorder.

Alternative and complementary therapies greatly expand the range of therapeutic choices for patients suffering pain. Today, patients are increasingly seeking these therapies—not just to treat pain but also to address many other common health conditions. Various theories have been offered to explain the increased interest in alternative and complementary therapies.

Understanding the alternative trendWhy are more people turning to alternative and complementary therapies to treat health problems? One reason is that most therapies are noninvasive and cause few adverse reactions.

People with certain chronic conditions may be drawn to these therapies because conventional medicine has few, if any, effective treatments for them. Also, people are encouraged by reports that document their effectiveness.

| Hoopla about holism Conventional medicine tends to treat only signs and symptoms, whereas alternative and complementary therapies focus on the whole person, thus holism. |

| Time—and more time Many people also value the extra time alternative practitioners spend with the patient and the attention they pay to the patient’s temperament, behavioral patterns, and perceived needs. In an increasingly stressful world, people are searching for someone who will take the time to listen to them and treat them as people, not just bodies displaying signs and symptoms. |

| Spiritual hunger Some people view modern society as spiritually malnourished and hungry for meaning. Alternative practitioners seem to be more responsive to this need. |

| Cultural connections Lastly, in a culturally diverse country such as the United States, a wide variety of traditional healing practices and beliefs exist. Some are based on the same principles that underlie alternative and complementary therapies. |

Regardless of the problem for which they’re used, alternative and complementary therapies address the whole person—body, mind, and spirit—rather than just signs and symptoms.

Although alternative and complementary therapies are usually discussed together, they aren’t exactly the same:

Alternative therapies are those used instead of conventional or mainstream therapies—for example, the use of acupuncture rather than analgesics to relieve pain.

Complementary therapies are those used in conjunction with conventional therapies—such as meditation used as an adjunct to analgesic drugs.

Some of the alternative and complementary therapies practiced today have been used since ancient times and come from the traditional healing practices of many cultures—particularly in the Eastern part of the world.

Many mainstream Western doctors have become more open-minded about these therapies. In fact, some medical doctors even administer them. However, others still object to them on the grounds that they aren’t based solely on empirical science.

Nonetheless, alternative and complementary therapies commonly relieve some types of pain that don’t respond to Western techniques. They may prove especially valuable when a precise cause evades Western medicine, as typically occurs in chronic low back pain.

Cognitive approaches to pain management focus on influencing the patient’s interpretation of the pain experience. Behavioral approaches help the patient develop skills for managing pain and changing his reaction to it.

Cognitive and behavioral approaches to managing pain include meditation, biofeedback, and hypnosis. These techniques improve the patient’s sense of control over pain and allow him to participate actively in pain management.

Meditation is thought to relieve stress and reduce pain through an effect called the relaxation response—a natural protective mechanism against overstress. Learning to activate the relaxation response through meditation may offset some of the negative physiologic effects of stress.

Biofeedback uses electronic monitors to teach patients how to exert conscious control over autonomic functions. By watching the fluctuations of various body functions on a monitor, patients learn how to change a particular body function by adjusting thoughts, breathing pattern, posture, or muscle tension.

As they modify vital functions, patients may develop the ability to control pain without using conventional treatments.

Hypnosis harnesses the power of suggestion and altered levels of consciousness to produce positive behavior changes and treat various conditions. Under hypnosis, a patient typically relaxes and experiences changes in respiration, which may lead to a positive shift in behavior and a greater sense of well-being.

References

Egan, M., & Cornally, N. (2013). Identifying barriers to pain management in long-term care. Nursing Older People, 25(7), 25–31.

Fielding, F., Sanford, T. M., & Davis, M. P. (2013). Achieving effective control in cancer pain: A review of current guidelines. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 19(12), 584–591.

![]()

- Which medication is used to reverse the effects of narcotic overdose?

- Thermotherapy causes which effect?

- Massage promotes increased circulation and softening of connective tissues. It also has which effect?

If you answered all three questions correctly, wow! You must be feelin’ great!

If you answered all three questions correctly, wow! You must be feelin’ great! If you answered two questions correctly, good job! You sure don’t have any opioids clouding your brain.

If you answered two questions correctly, good job! You sure don’t have any opioids clouding your brain. If you answered fewer than two questions correctly, feel no pain! Review the chapter and try again.

If you answered fewer than two questions correctly, feel no pain! Review the chapter and try again.Outline