The healthcare environment is fast paced and constantly changing. Shortly after passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, for example, nurses and other healthcare providers were already contemplating its impact on their duties (Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, 2019). We had embraced recommendations from the Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2010) with regard to the scope of practice for nurses and, among other things, had embarked on sweeping changes in nursing education to advance the doctorate as the expected educational preparation for advanced nursing practice. In hindsight, much of what we thought would be a force for change in nursing practice, education, and health care has happened, leading to a better understanding of the effects of those events.

We continue to grapple with the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (2019), changes in the administration of the Act, and its influence on the number of uninsured in the United States. Increasing the number of Americans with health insurance increases access to healthcare services; however, along with an aging population, it has also resulted in a steeply increasing demand for primary care providers such as nurse practitioners (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2013). Colleges and universities are expanding enrollment in graduate programs to prepare advanced practice nurses, but the shortage of faculty, clinical sites, qualified preceptors, and other finite or dwindling resources continue to limit the expansion of graduate education for nurses, and thousands of qualified students are denied entry to programs each year (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2017).

Moreover, the Affordable Care Act (2019) has adjusted reimbursement rates and policies, resulting in major shifts in healthcare institutions. The attention to reducing readmissions, limiting or eliminating payment for hospital-acquired illness and injury, increasing patient satisfaction, and rewarding institutions that improve patient outcomes are important and necessary inducements to promote quality of patient care. Since Linda Aiken’s groundbreaking work in 2003, there has been a substantial body of evidence indicating that baccalaureate preparation for nurses improves patient outcomes (Blegen et al., 2013; Kutney-Lee et al., 2013; McHugh et al., 2013) and is likely to reduce costs through a reduction in length of stay (Yakusheva et al., 2014) and readmissions (McHugh & Ma, 2013). As a result of improved care, trends in data suggest that there will be fewer patients in hospitals, producing a decreased demand for nurses working in those settings and an increase in demand in outpatient, ambulatory, clinic, community, occupational, and long-term settings (Wadhwani & LeBuhn, 2014). Educational programs are in the midst of adjusting curricula to prepare nurses at the undergraduate and graduate level to manage care, ensure good patient outcomes, and lead healthcare quality improvements in these environments.

The healthcare environment is rapidly evolving, and nurses will need to consider how to prepare for shifts in employment demand. The Joint Statement from the AACN (2015) sets forward principles that community colleges, educational accrediting bodies, and universities may use to promote the further education of a diverse and well-prepared nursing workforce to meet the demands of the 21st century. The call for 80% of all registered nurses to be prepared at the baccalaureate level by 2020 (IOM, 2010), combined with the strong push for Magnet certification (American Nurses Credentialing Center [ANCC], 2015) among many top-tier hospitals, has been a strong motivating force behind the increase in the number of nurses returning to complete their bachelor of science in nursing degree. It remains to be seen if those nurses will go on to complete graduate degrees, including the doctorate, to meet the healthcare needs of the future.

What does any of this have to do with the acquisition and application of statistics, quantitative reasoning skills, and evidence-based practice? What we know is that nurses across all settings, and with all manner of experience and educational preparation, are being asked to step up and do their part to ensure:

- The care that patients, families, and communities receive is of the highest quality.

- That care is substantiated in the best quality evidence.

- That the delivery of care takes place in an environment that values perspectives from all health-related disciplines.

The quality bar for nursing practice is being raised. One way that nurses can be certain that their leadership to improve healthcare practice and patient outcomes is effective is to learn the fundamental concepts of statistical reasoning and apply those skills to evidence-based practice. As a nurse, you are accountable every day to your patients, your employer, and your profession to make certain that the quality of care you deliver is the best available. Your professional experience and previous training, although important, are not enough to safeguard the public’s confidence in the quality of nursing care. Over time, new knowledge and information become available, and your ability to engage in evidence-based practice, quality improvement, and process improvement are based on scientific review and hold the key to providing high-quality nursing care.

Statistics is an important tool of evidence-based practice, and we commend you for deciding to improve your skills by taking a statistics course or reading this text. As a nurse with advanced education in statistics and evidence-based practice, you will be better qualified to make important contributions to health care, nursing practice, and the well-being of patients across a variety of settings.

By now, you are undoubtedly aware that the quality of health care in the United States is dependent upon the quality of nursing care (IOM, 2010). Logically, the better prepared nurse is more likely to promote safety and quality of patient care through evidence-based practice. Recognizing the important role that advanced practice nurses have in the healthcare system, the AACN (2006) has recommended that the doctor of nursing practice (DNP) degree be the educational entry level for advanced practice nurses, and there is a consensus that the DNP is well suited for those nurses in leadership roles as well. To meet this expectation, we contend that nurses pursuing graduate education need a strong understanding of statistics to implement evidence-based practice and all its permutations. This text is designed to help nurses develop the skills necessary to carry out evidence-based practice.

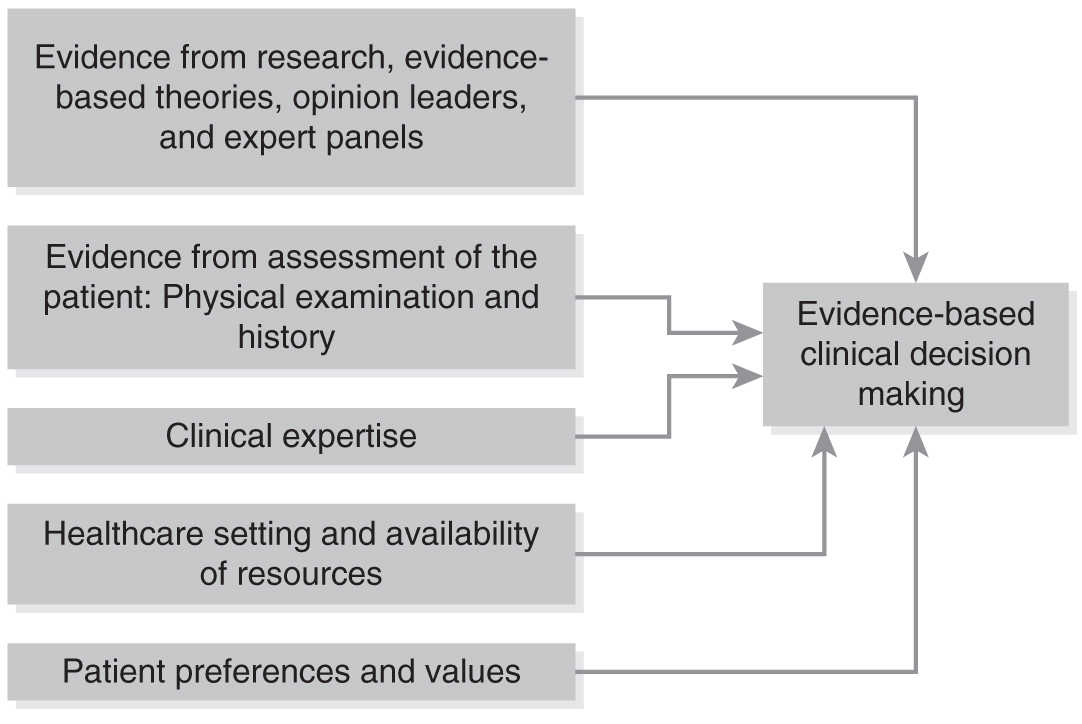

Evidence-based practice is clinical decision making using the best evidence available in the context of individual patient preferences by well-informed expert clinicians (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2005). There are many kinds of evidence that nurses can integrate into their practice (see Figure 1-1). We strive to use the best-quality evidence available. Types of evidence range from our professional experience and expert opinion to substantiated theoretical propositions and findings from research. The volume and quality of evidence available depends on the nature of the clinical problem. Levels of evidence are one useful way to think about what kinds of evidence are available, how these are connected to statistical tests, and what kinds of clinical questions each type of evidence can answer.

Elements of evidence-based practice.

A flow diagram shows clinical decision making, by using the best evidence available.

Modified from Melnyk, B. M., & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2005). Evidence-based practice in nursing and healthcare. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

CASE STUDY| Evidence-Based Practice Do you know of a family member, friend, or coworker who has problems sleeping? If any of these individuals seek health care from a nurse practitioner or physician, what should he or she expect? Most patients expect that interventions for their healthcare problems are based on current scientific evidence. Dr. Valerio shares the following story: Nurses have always been concerned about preventing health problems and treating health problems with self-care measures in addition to nursing care. At the beginning of my nursing career, in the late 1970s, sleep problems such as chronic insomnia were treated only with drugs. We thought that sleep problems were caused by anxiety and may affect good health; however, we did not have evidence about how to prevent chronic insomnia or treat this sleep disorder without the use of drug therapy that can cause concerning side effects. At that time, and for over a decade later, there was little research that showed the efficacy of behavioral therapy for insomnia. With the shift in healthcare focus to prevention, chronic disorders, and outpatient care, a greater emphasis was placed on understanding and treating sleep problems. Through the amassing of scientific evidence, we learned that chronic insomnia is the result of conditioning, and that behavioral treatments can produce long-term improvement in sleep without concerning side effects. This therapeutic approach is particularly important to APNs who strive to teach patients self-care skills and reduce unnecessary use of pharmacologic therapy. Now that we know the best practices to treat chronic insomnia, we are challenged to implement these interventions into everyday clinical practice. Our patients expect the best care available from nurses. We should partner with our patients to use scientific findings, their individual needs, and our clinical judgment to support improvement in their health. This is the essence of evidence-based practice. |

Let’s examine the levels of evidence table (see Table 1-1). Keep in mind that the evidence table is similar to a healthy diet—that is, you need a bit of everything to have a good understanding of any given clinical situation or problem. Let us consider the problem of pressure ulcers. We could ask a question such as, “What is the patient experience of pain associated with a pressure ulcer?” Such a question would be best answered with evidence from descriptive studies in which researchers asked patients with a pressure ulcer about associated pain. In contrast, if we wanted to know whether a wet-to-dry dressing or a hydrophilic dressing was best for healing a pressure ulcer, evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing these two approaches would be the most useful. The nurse needs to skillfully interpret reports of investigations, including the statistical results, in order to determine the quality of the evidence and the applicability to any given clinical situation. Each type of research approach, ranging from exploratory to experimental, has its own statistical analysis that corresponds to the kind of research question that is being asked and the type of data that have been collected. There are many valid forms of evidence, such as expert opinion and findings from qualitative studies; however, because this text is focused on statistics and evidence-based practice, we will limit our discussion to approaches that use statistical methods for analyzing data.

Type of Research Evidence | Uses | Strength of the Evidence |

|---|---|---|

Descriptive or exploratory research (single studies that report frequencies, averages, and variation) | Helps to answer questions about the nature of a problem (population or phenomenon being studied), such as “How many people are affected?” or “What is the subjective patient experience?” | Best evidence for describing problems or concerns in health care |

Correlational research (single studies that report correlation coefficients such as Pearson’s r) | Provides information about the relationship between factors, such as, “Is body weight related to the formation of pressure ulcers?” | Useful evidence for beginning to understand complex health problems |

Comparative research (single studies that report on differences between groups using t-tests or analysis of variance [ANOVA]) | Helps to answer questions about how two or more groups are different on some measure(s), for example, “Does blood pressure vary between men and women?” | Evidence from these studies may be combined with correlational research to better describe the factors influencing health |

Case-controlled and cohort studies (single “natural experiments” that help us predict outcomes) | Provides information on what factors might influence or predict health outcomes, such as “Does smoking predict lung cancer?” | Strong preliminary evidence for examining cause and effect |

Experimental trials or randomized controlled trials (single studies that test cause and effect) | Studies examine the effect of an intervention on patient outcomes. For example, “Does turning a patient every two hours prevent pressure ulcers?” | Very good evidence for examining cause and effect, especially the effect of interventions on patient outcomes |

Meta-analyses (analyses of existing randomized controlled trials to determine the effectiveness of interventions) | These studies combine many previous experiments on one or more interventions and their effects on a patient outcome to answer a question such as, “What do all of the studies on patient turning tell us about the effect on pressure ulcers?” | Strongest evidence for cause and effect and the effectiveness of an intervention |