Methods of Administering Local ED Drugs

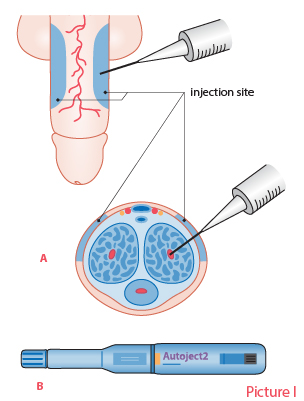

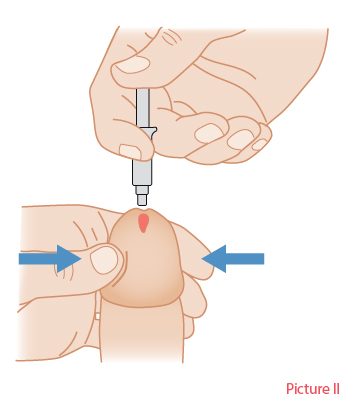

Methods of administering local ED drugs.Picture I. Injectable drugs. Injection technique (A) and auto-injector (Autoject 2) for administering an injectable drug (B). Picture II. Topically administered drug. Introduce some of the cream into the urethra.

Picture I: Piha J. [Steps of pharmacotherapy]. In: Brusila P, Kero K, Piha J et al (eds.). [Sexual Medicine]. Helsinki: Duodecim Publishing Company 2020. Picture II: Duodecim Publishing Company.

Primary/Secondary Keywords

- erectile dysfunction

- ED

- penile erection

- local drug administerion

- injection treatment

- alprostadil