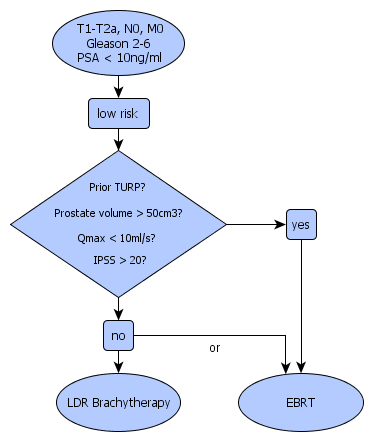

Radiotherapy for Low Risk Prostate Cancer

This guideline is modified from the NCCN guidelines by Department of Oncology, Helsinki University Hospital. The input data (clinical stage, PSA, Gleason score) indicate that this patient has low risk for disease progression. Please check the correctness of the input data before making decions on treatment.

Prostate Cancer Calculator and Decision Support Tool http://www.mskcc.org/mskcc/html/10088.cfm