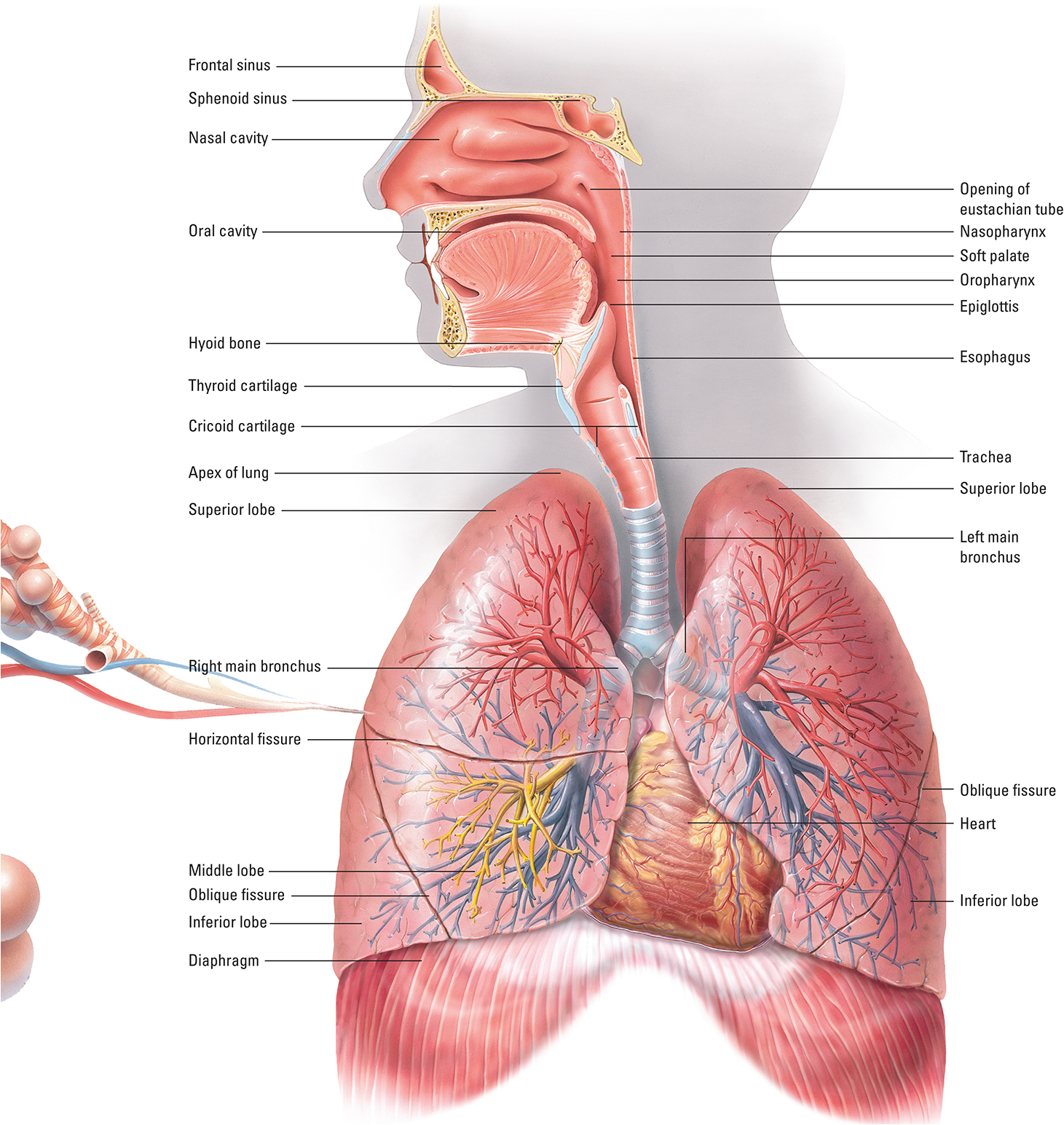

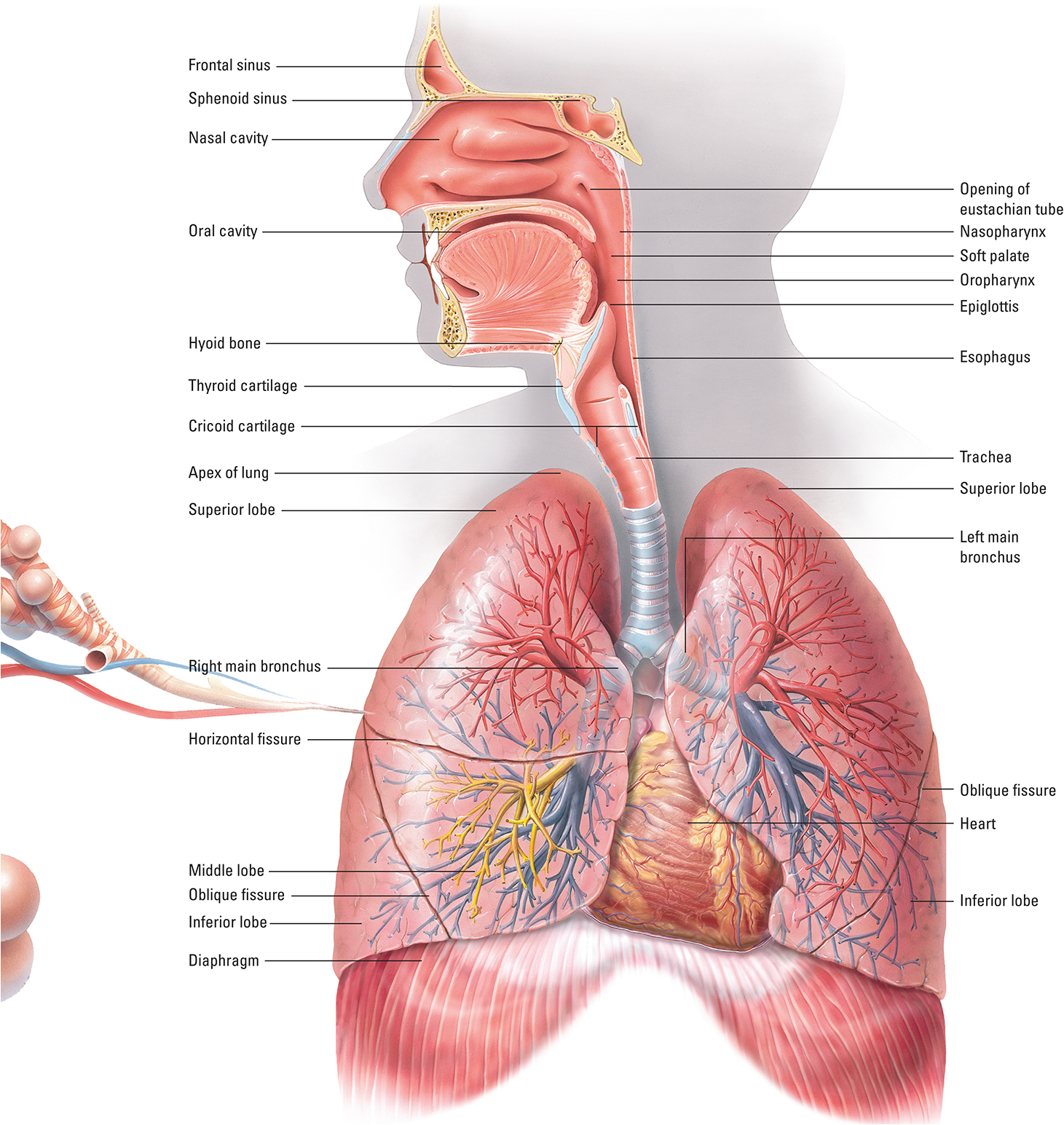

The respiratory system is divided into the upper respiratory tract and the lower respiratory tract. The upper respiratory tract consists of the nose, mouth, nasopharynx, oropharynx, laryngopharynx, and larynx. The lower respiratory tract consists of the trachea, lungs, left and right mainstem bronchi, five secondary bronchi, and bronchioles. The left mainstem bronchus has two lobes, and the right mainstem bronchus has three lobes. Each lung is protected by a pleural membrane. The visceral pleura attaches to the outer surface of the lung, whereas the parietal pleura lines the inside of the thoracic cavity.

Respiration

Effective respiration requires gas exchange in the lungs (external respiration) and in the tissues (internal respiration). Three external respiration processes are needed to maintain adequate oxygenation and acid-base balance:

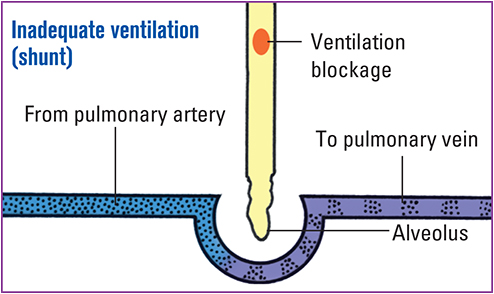

Ventilation (gas distribution into and out of the pulmonary airways)

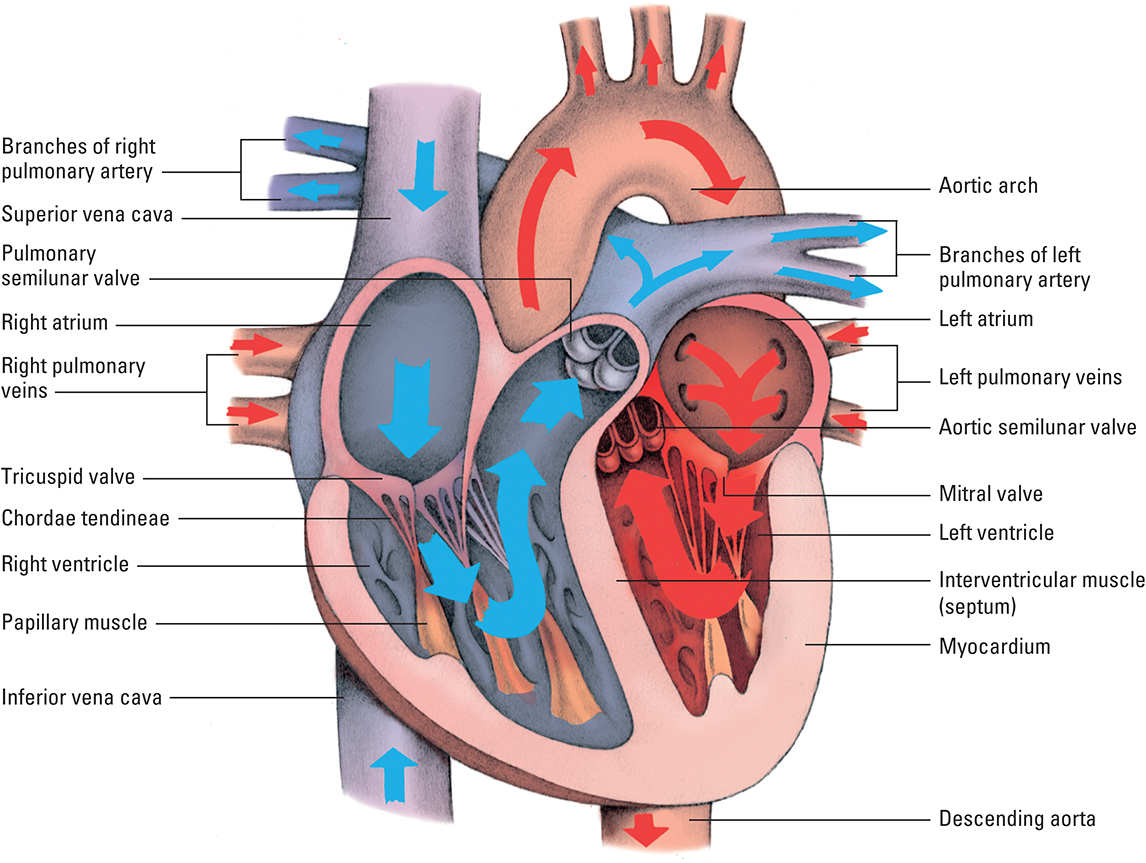

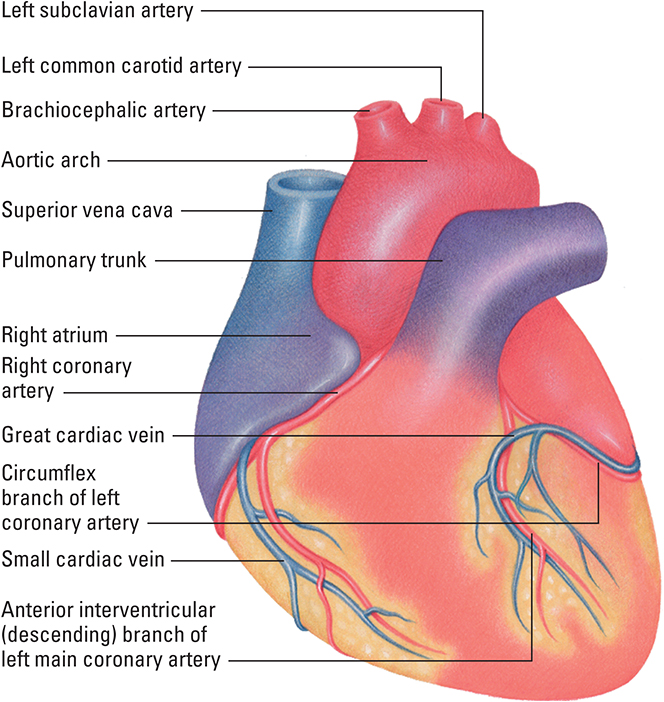

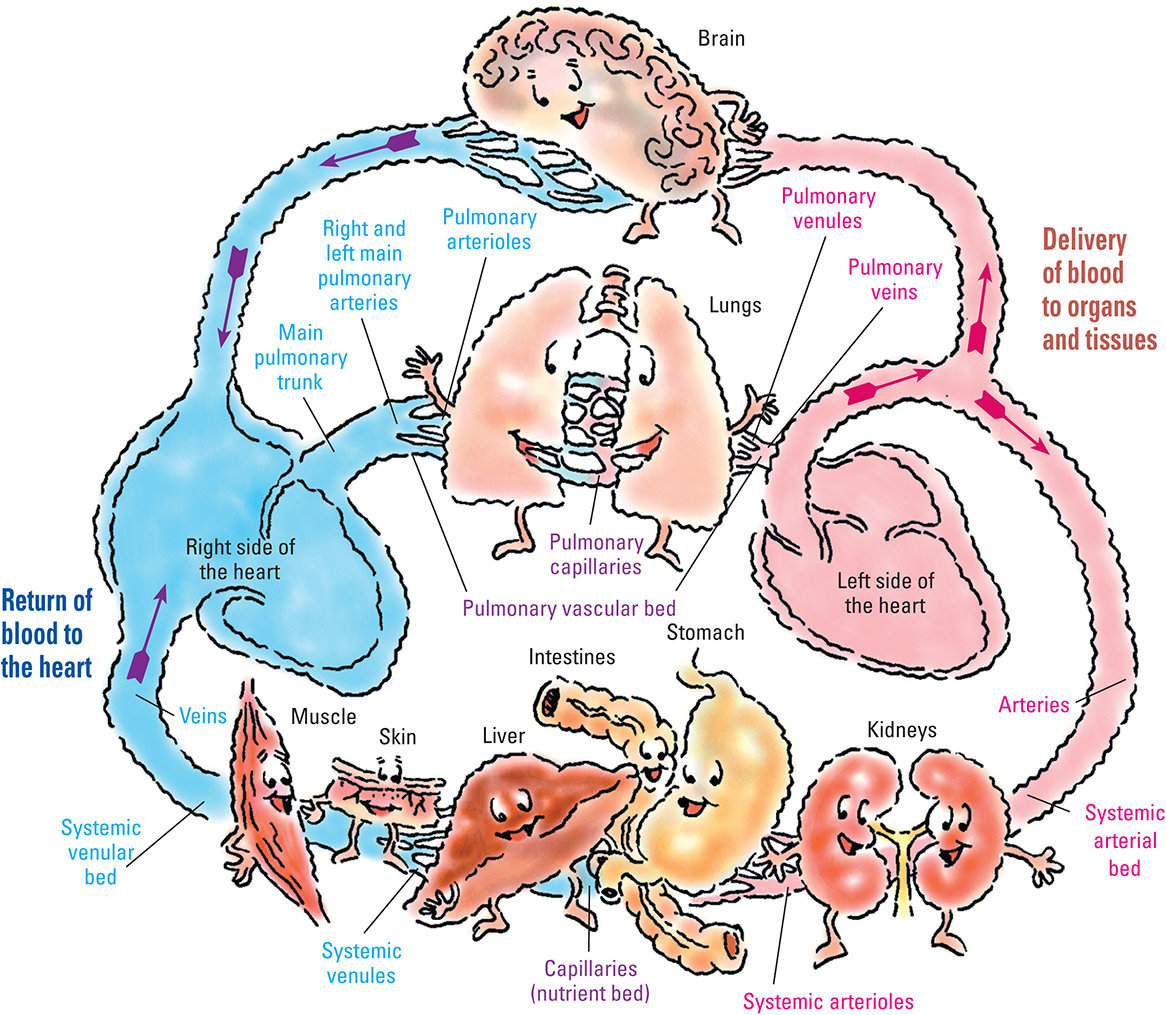

Pulmonary perfusion (blood flow from the right side of the heart, through the pulmonary circulation, and into the left side of the heart)

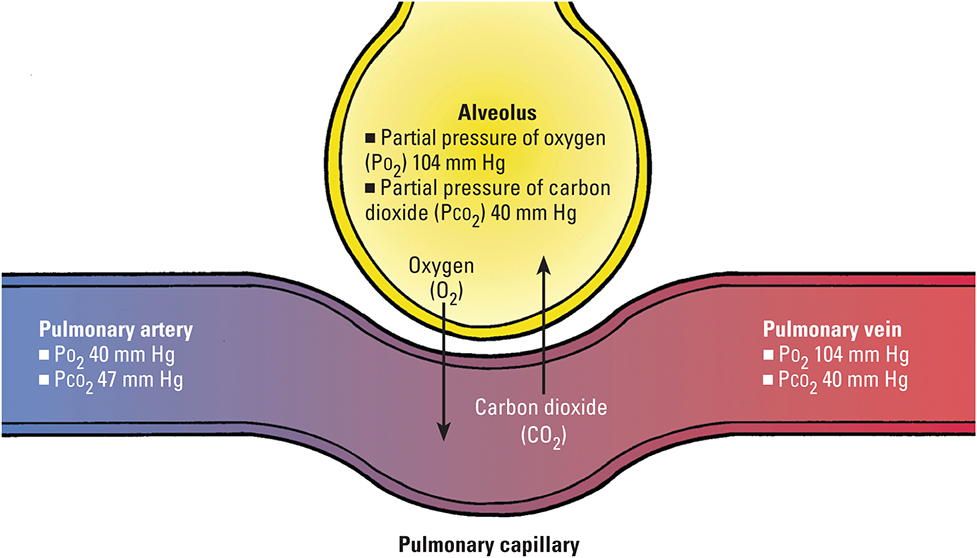

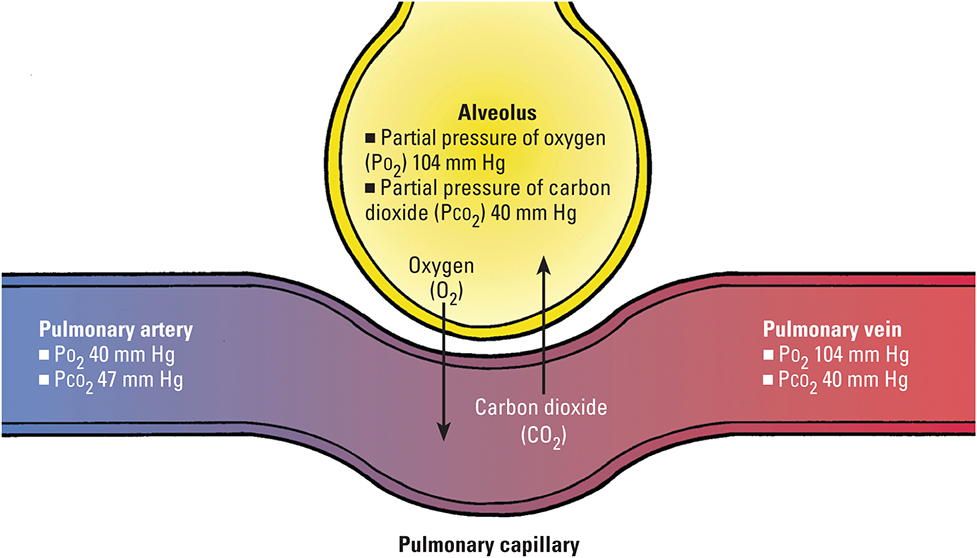

Diffusion (gas movement from an area of greater concentration to an area of lesser concentration through a semipermeable membrane): Deoxygenated blood enters the pulmonary capillaries, which have lower partial pressure of O2 in inhaled alveolar air.

Ventilation

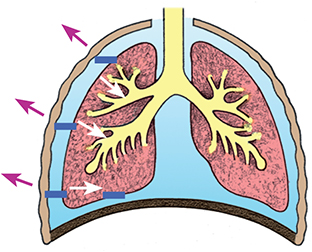

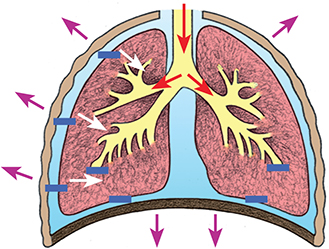

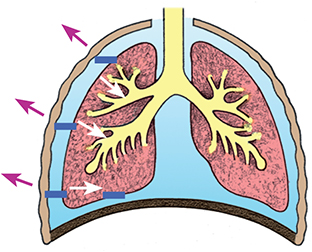

Breathing, or ventilation, is the movement of air into and out of the respiratory system. During inspiration, the diaphragm extends downward to allow a greater area for lung expansion. The external intercostal muscles contract, causing the rib cage to expand and the volume of the thoracic cavity to increase. Air then rushes in to equalize the pressure. The air moves throughout the respiratory tract down to the alveoli, where gas exchange takes place. During expiration, the lungs passively recoil as the diaphragm and intercostal muscles relax, pushing air out of the lungs. CO2 is then expired.

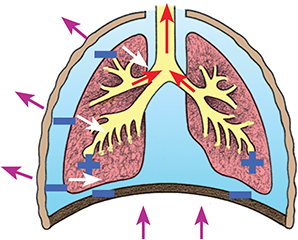

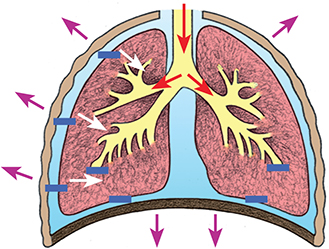

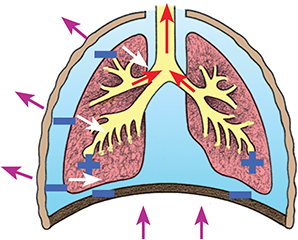

The mechanics of breathing

Mechanical forces, such as movement of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles, drive the breathing process, which is a response to the changes in the atmospheric pressure within the alveoli and pleural cavity. In the figures that follow, a plus sign (+) indicates positive pressure, and a minus sign (–) indicates negative pressure.

At restInspiratory muscles relax.

Atmospheric pressure is maintained in the tracheobronchial tree.

Atmospheric pressure = pressure in the alveoli and lungs.

No air movement occurs.

ExpirationInspiratory muscles relax, causing the lungs to recoil to their resting size and position.

The diaphragm ascends.

Positive alveolar pressure is maintained.

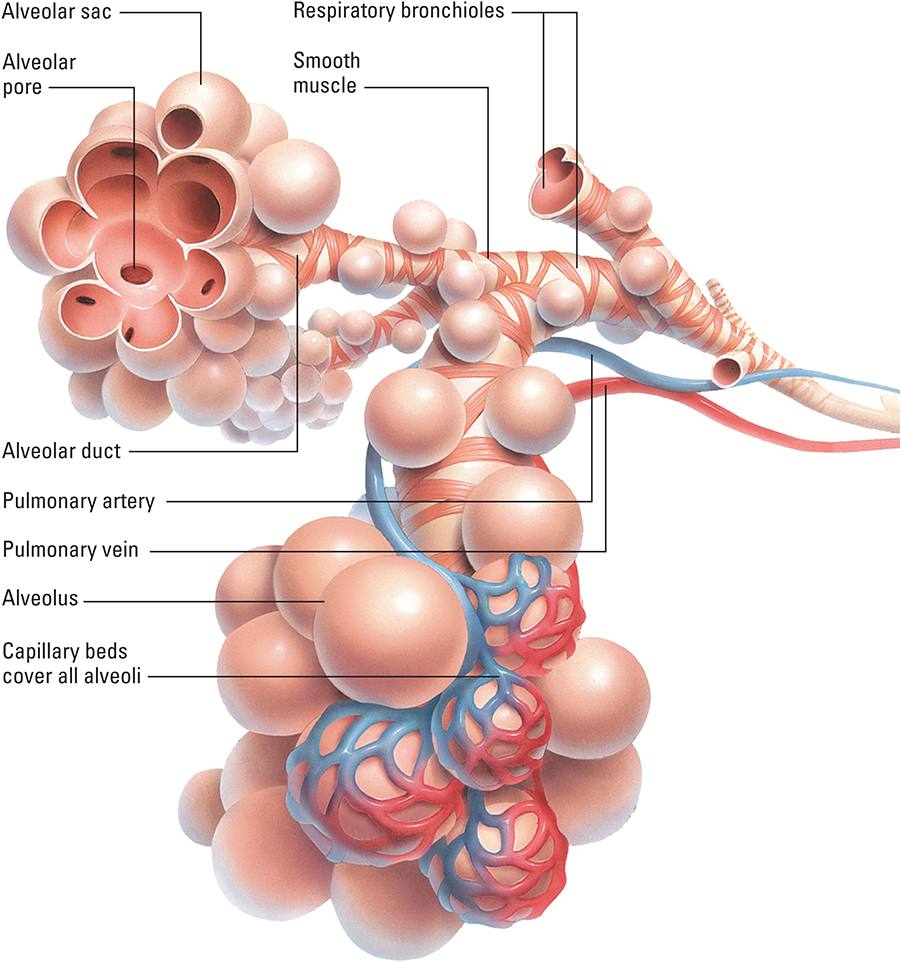

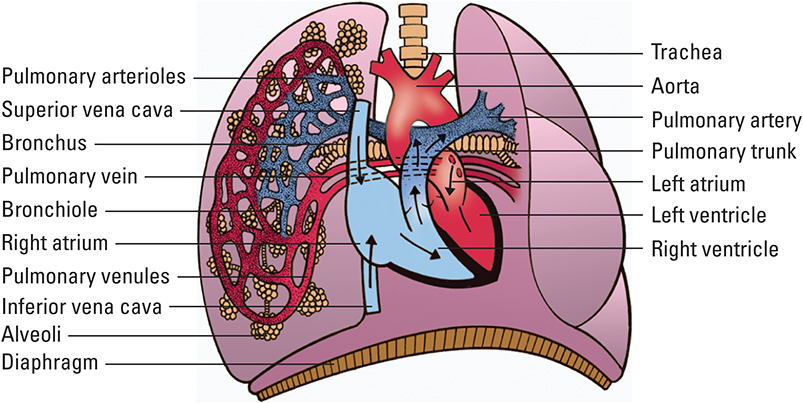

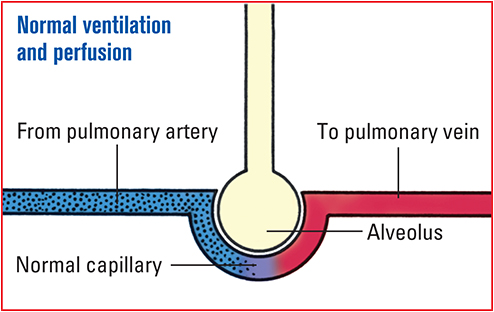

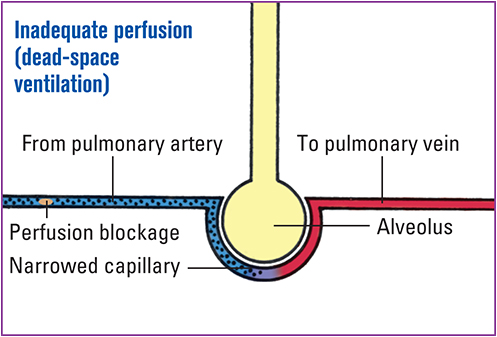

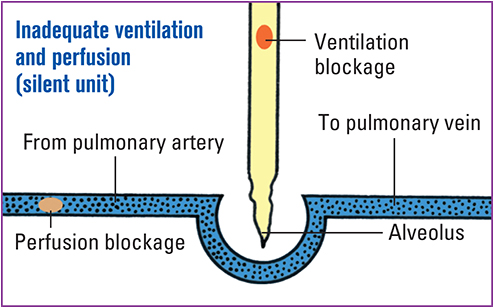

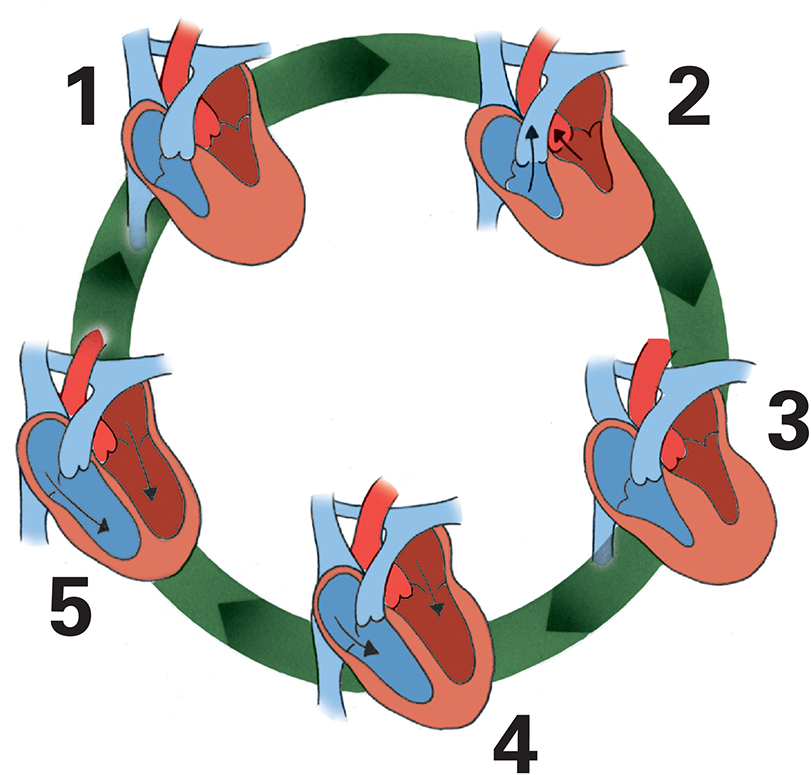

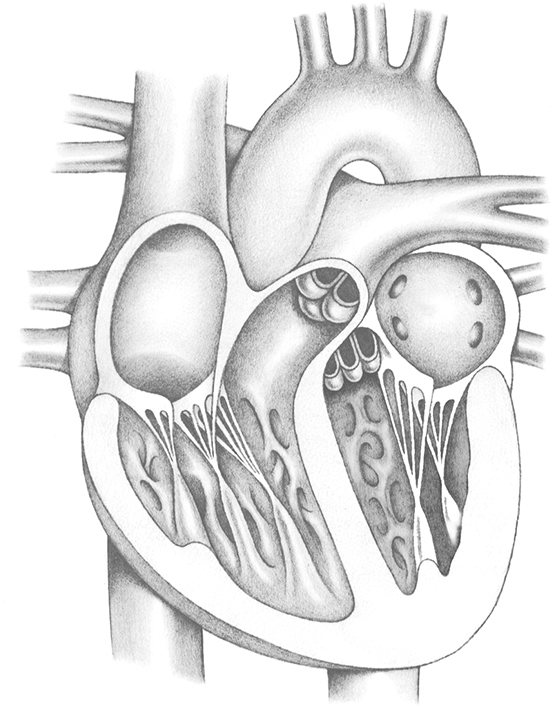

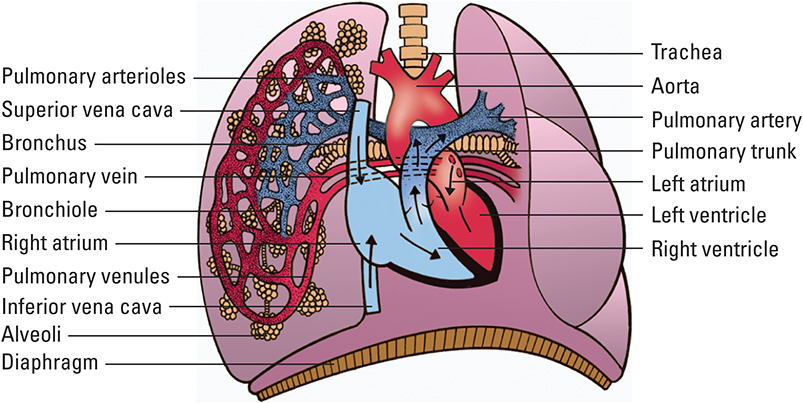

Pulmonary perfusion

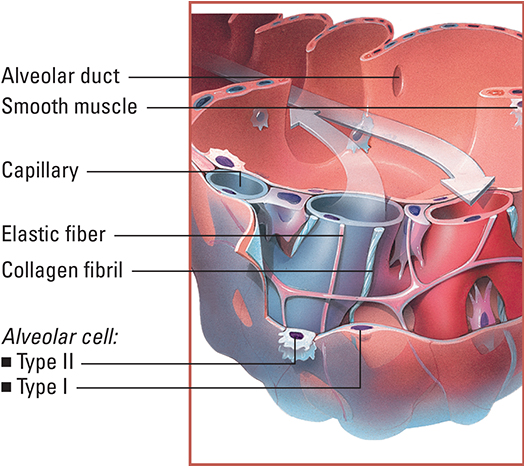

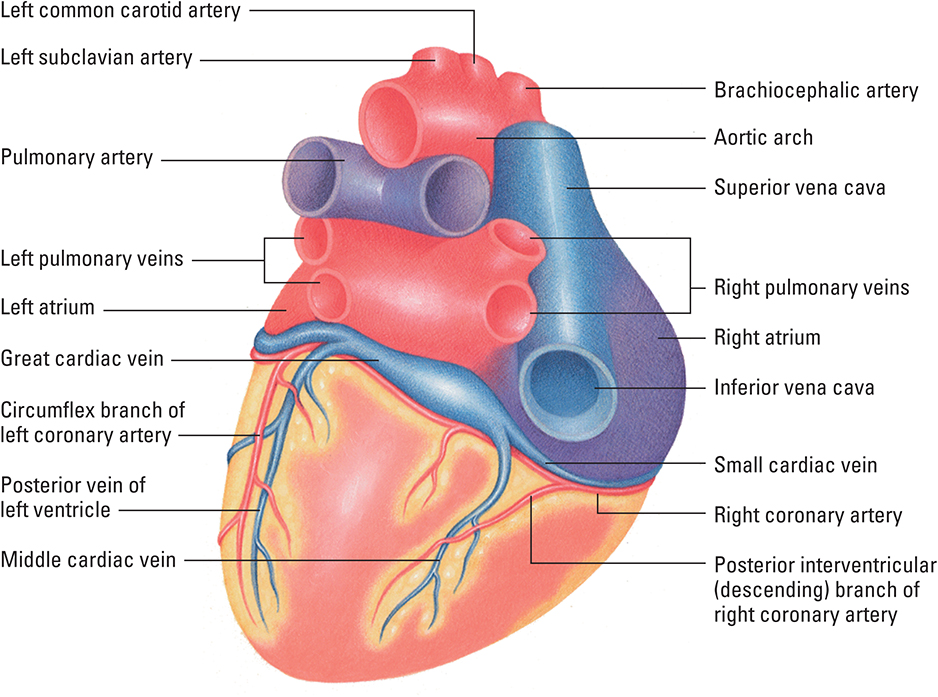

Blood flow through the lungs is powered by the right ventricle. The right and left pulmonary arteries carry deoxygenated blood from the right ventricle to the lungs. These arteries divide to form distal branches called arterioles, which terminate as a concentrated capillary network in the alveoli and alveolar sac, where gas exchange occurs. After the deoxygenated blood flows from the right side of the heart through the pulmonary circulation, oxygenated blood is delivered to the left side of the heart.

Venules-the end branches of the pulmonary veins-collect oxygenated blood from the capillaries and transport it to larger vessels, which carry it to the pulmonary veins. The pulmonary veins enter the left side of the heart and distribute oxygenated blood throughout the body.

Tracking pulmonary perfusion

Pulmonary vascular resistance

Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) refers to the resistance in the pulmonary vascular bed against which the right ventricle must eject blood. PVR is largely determined by the caliber and degree of tone of the pulmonary arteries, capillaries, and veins and is measured with the use of hemodynamic monitoring. Because these vessels are thin walled and highly elastic, PVR is normally very low. However, PVR may be easily influenced by vasoactive stimuli that dilate or constrict the pulmonary vessels or affect the tone of these vessels.

Factors that increase PVR include:

vasoconstricting drugs

hypoxemia

acidemia

hypercapnia

atelectasis.

Factors that decrease PVR include:

Diffusion

Blood in the pulmonary capillaries gains O2 and loses CO2 through the process of diffusion (gas exchange). In this process, O2 and CO2 move from an area of greater concentration to an area of lesser concentration through the pulmonary capillary, a semipermeable membrane.

Diffusion across the alveolar–capillary membrane

This illustration shows how the differences in gas concentration between blood in the pulmonary artery (deoxygenated blood from the right side of the heart) and alveolus make this process possible. Gas concentrations depicted in the pulmonary vein are the end result of gas exchange and represent the blood that is delivered to the left side of the heart and systemic circulation.