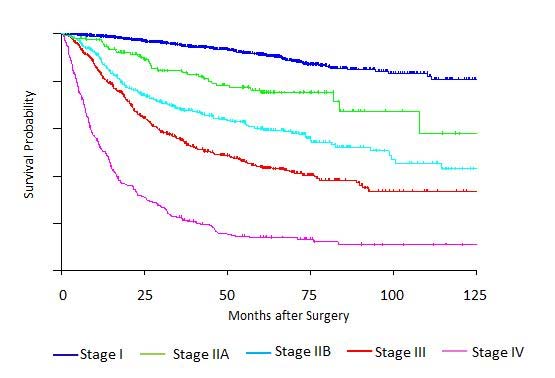

Clinical Classification

Designated as cTNM, clinical stage is based on evidence of extent of disease present before therapy is instituted. It includes physical examination, laboratory testing, radiologic imaging, endoscopy (possibly including endoscopic ultrasonography [EUS] with fine-needle aspiration [FNA] for cytologic assessment), and biopsy (for histologic confirmation), and may include diagnostic laparoscopy with peritoneal washings for cytologic/histologic assessment.

Clinical T Category

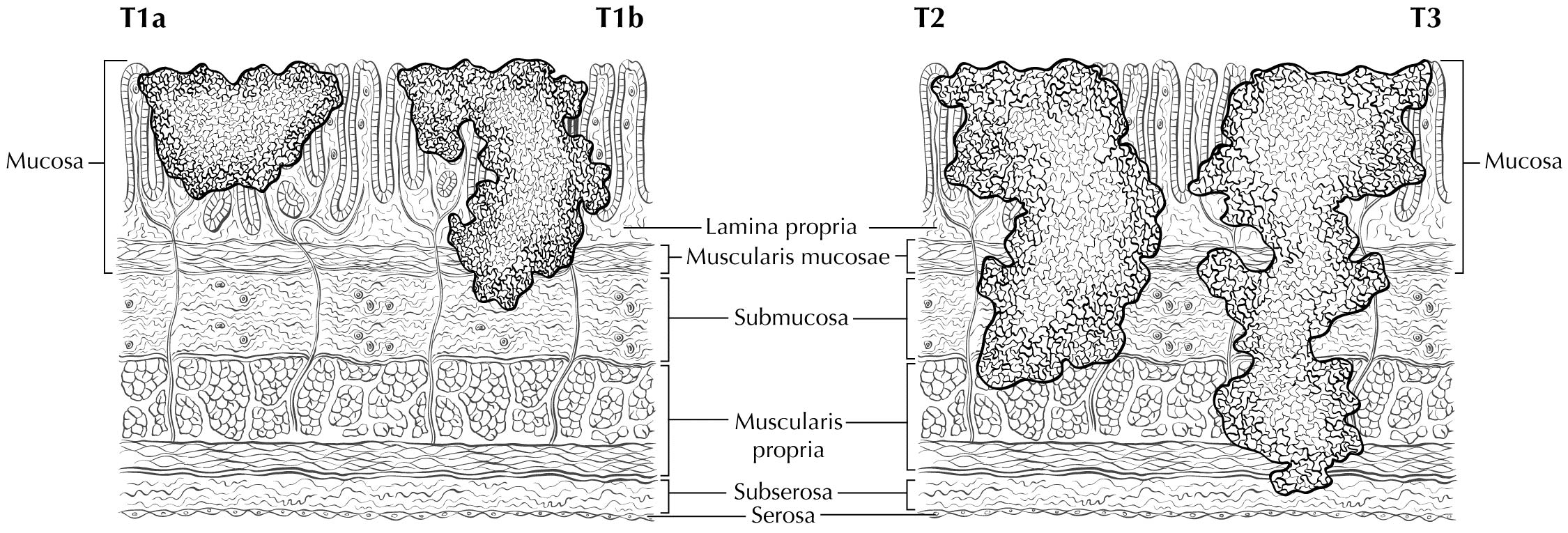

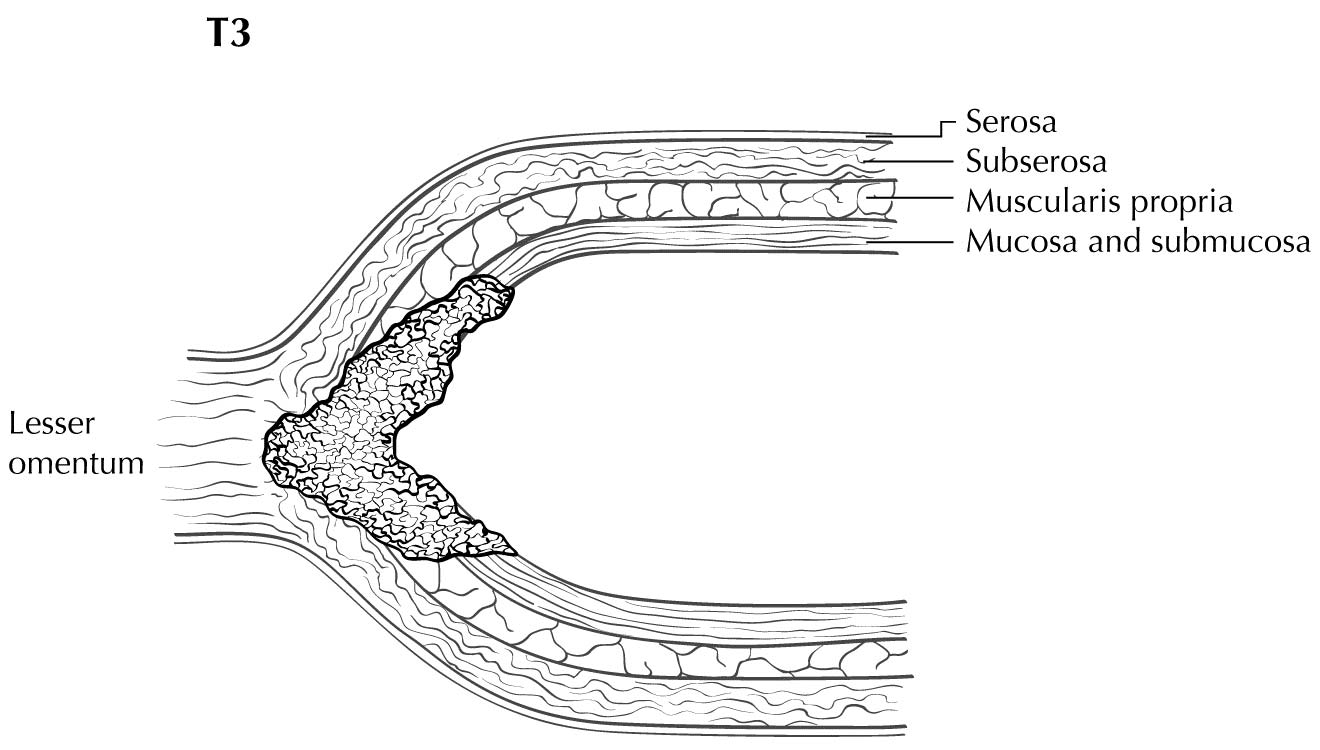

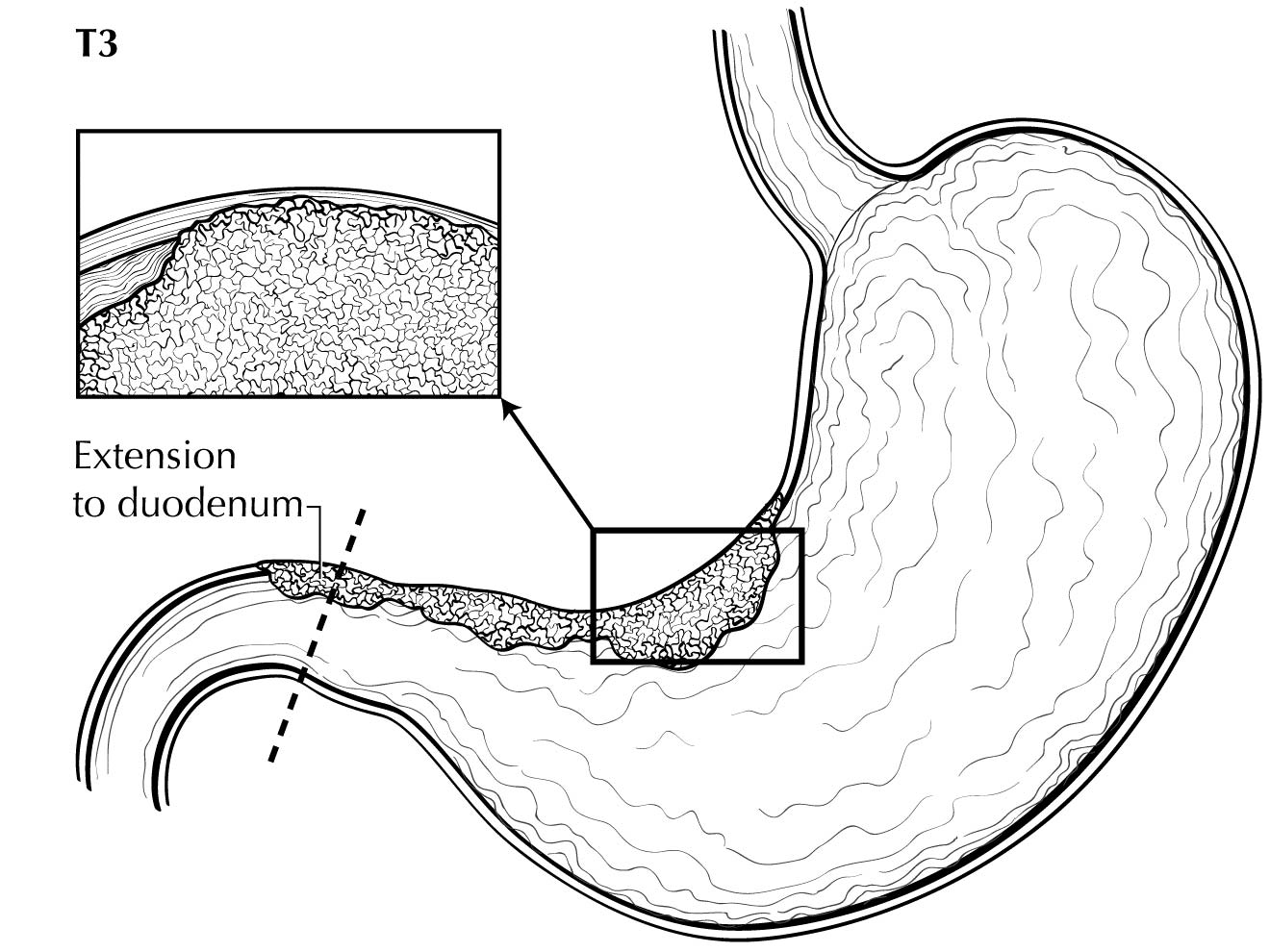

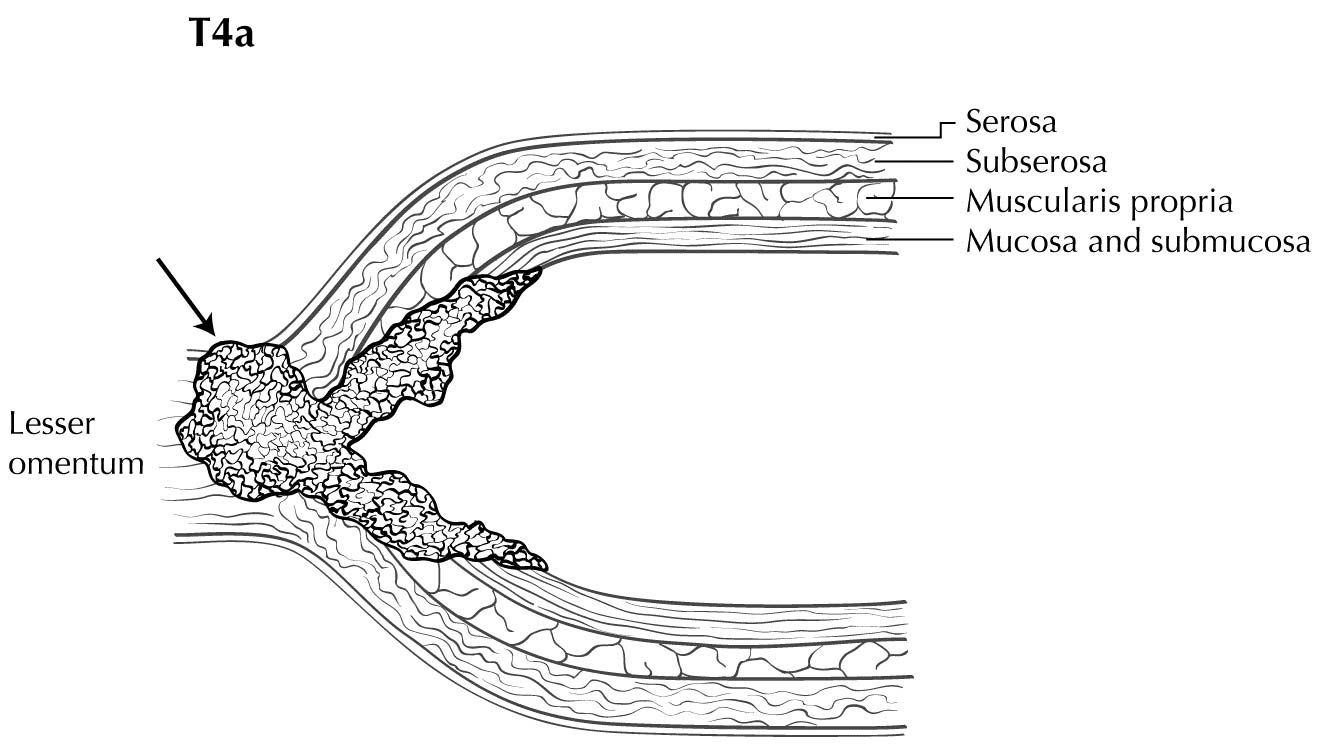

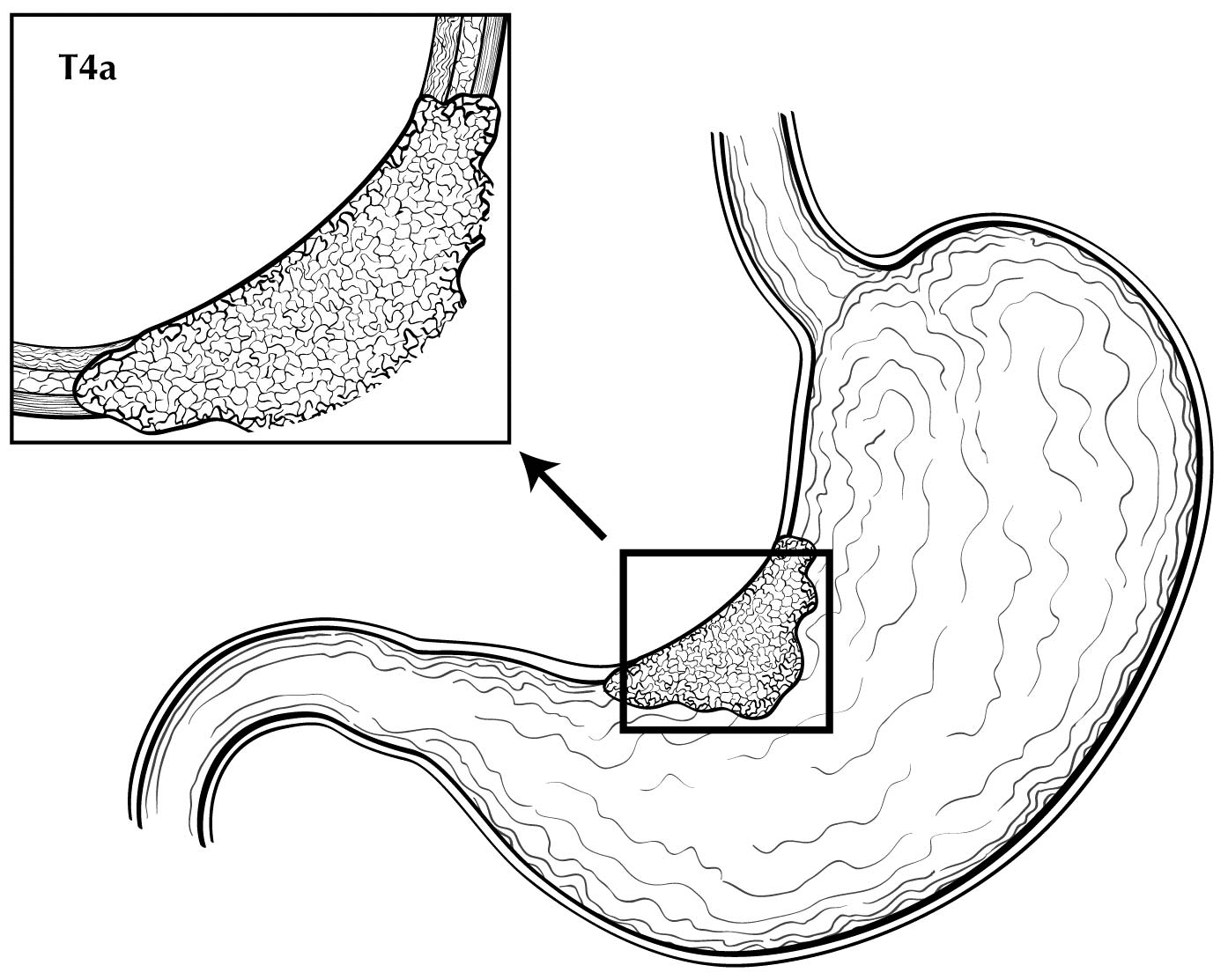

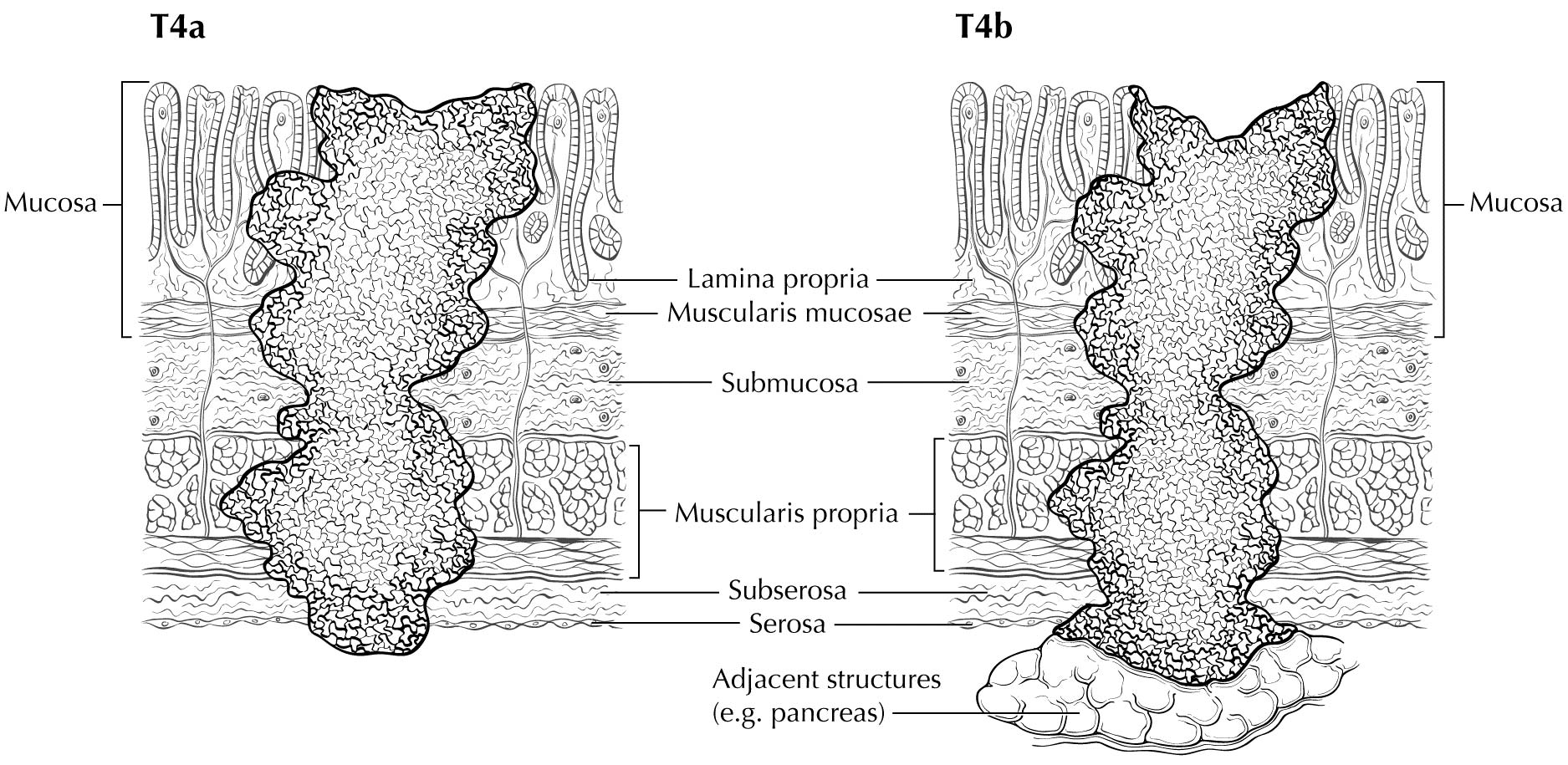

Staging of primary gastric adenocarcinoma depends on the depth of penetration of the primary tumor. The T1 designation is subdivided into T1a (invasion of the lamina propria or muscularis mucosae) and T1b (invasion of the submucosa). T2 is invasion of the muscularis propria, and T3 is invasion of the subserosal connective tissue without invasion of adjacent structures or the serosa (visceral peritoneum). T4 tumors penetrate the serosa (T4a) or invade adjacent structures/organs (T4b). EUS correlates highly with cT category. For tumors close to adjacent structures, radiologic imaging and EUS may help determine whether the adjacent anatomic structures are invaded (cT4a or cT4b).

Clinical N Category

Radiologic reports should document the number of enlarged nodes (with malignant features), and a multidisciplinary tumor board should review the images to document the number of nodes that appear malignant (see clinical staging methods in the next section). EUS also may be useful in identifying enlarged or malignant-appearing lymph nodes to determine cN category and may provide an opportunity to perform FNA or biopsy for cytologic assessment).

M Category for Clinical Staging

Imaging-based detection of organ metastasis (including peritoneal) is assigned cM1. This may be confirmed with tissue diagnosis, after which pM1 is assigned for the clinical stage. Confirmation of peritoneal metastasis by diagnostic laparoscopy or peritoneal washings performed as part of the staging workup is considered positive metastasis. Specifically, gross evidence of metastasis seen during diagnostic laparoscopy is cTcNcM1, whereas positive washings obtained during diagnostic laparoscopy without evidence of gross metastasis is considered cTcNpM1, which is clinical stage IV and pathological stage IV. See the detailed discussion in Chapter 1.

Endoscopy and Imaging

EUS and computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with oral and intravenous contrast are the initial imaging modalities used to determine clinical primary tumor (cT), node (cN), and metastasis (cM) categories. Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT with fluorine-18 (18F)-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging may be used to further refine cN category and cM category in locoregionally advanced cTcN.

Endoscopic Evaluations

Clinical assessment of depth of invasion and nodal involvement, as well as some limited areas of distant disease, may be facilitated by the use of EUS. Gastric cancer staging is best performed by using commercially available ultrasound endoscopes with multifrequency (5-, 7.5-, 10-, and 12-MHz) radial transducers. Sonographic evaluation is performed as the instrument is withdrawn, starting at the pylorus. Orienting the images in an anteroposterior axis permits careful assessment of anatomic land marks to allow correlation with the location of the tumor, nodes, and surrounding organs.

The individual layers of the gastrointestinal wall are visualized throughout the examination to correlate the extent of the tumor relative to the alternating bright and dark layers seen on ultrasound. On the basis of in vitro studies, the first two layers (bright and dark starting at the lumen) correspond to the superficial and deep mucosa, the third (bright) layer corresponds to the submucosa, the fourth (dark) layer to the muscularis propria, and the fifth (bright) layer to the adventitia or serosa.6

Alterations in the thickness of individual layers are easily and reproducibly identified, allowing one to determine the depth of tumor invasion. The presence of a mass in the stomach usually is diagnosed as a hypoechoic or dark thickening in one or more layers, or a loss of the usual layer pattern.7 The first bright layer, which represents a transition echo layer, rarely is lost or thickened. Thickening of the second, or inner dark, layer suggests a T1 tumor. Although at higher EUS frequencies of 10 or 12 MHz one should be able to distinguish tumors limited to the mucosa (T1a) from those extending into the submucosa (T1b), some studies have shown reduced accuracy with T1 staging.8-11 A dark thickening extending from the second to the third layer (mucosa and submucosa), but not reaching the fourth layer (muscularis propria), is evidence of a T1b tumor. A dark thickening extending to but not completely through the fourth layer with a preserved smooth outer echogenic border is associated with a T2 tumor. Complete loss of all the layers, associated with a smooth white outer layer representing the serosal surface, suggests penetration through the muscularis propria into the subserosal fat, consistent with a T3 tumor in the stomach. If there is extension of the dark wall thickening with loss of the serosal echogenic stripe, the tumor is staged T4a. The distinction between T3 and T4a by EUS may be very challenging, as the actual thickness of the subserosal fat may vary and the serosa is very thin and likely not seen clearly on EUS. Full transmural extension with loss of the echogenic stripe separating the stomach from surrounding structures, such as the aorta, pancreas, liver, or other adjacent structure, indicates a T4b tumor.

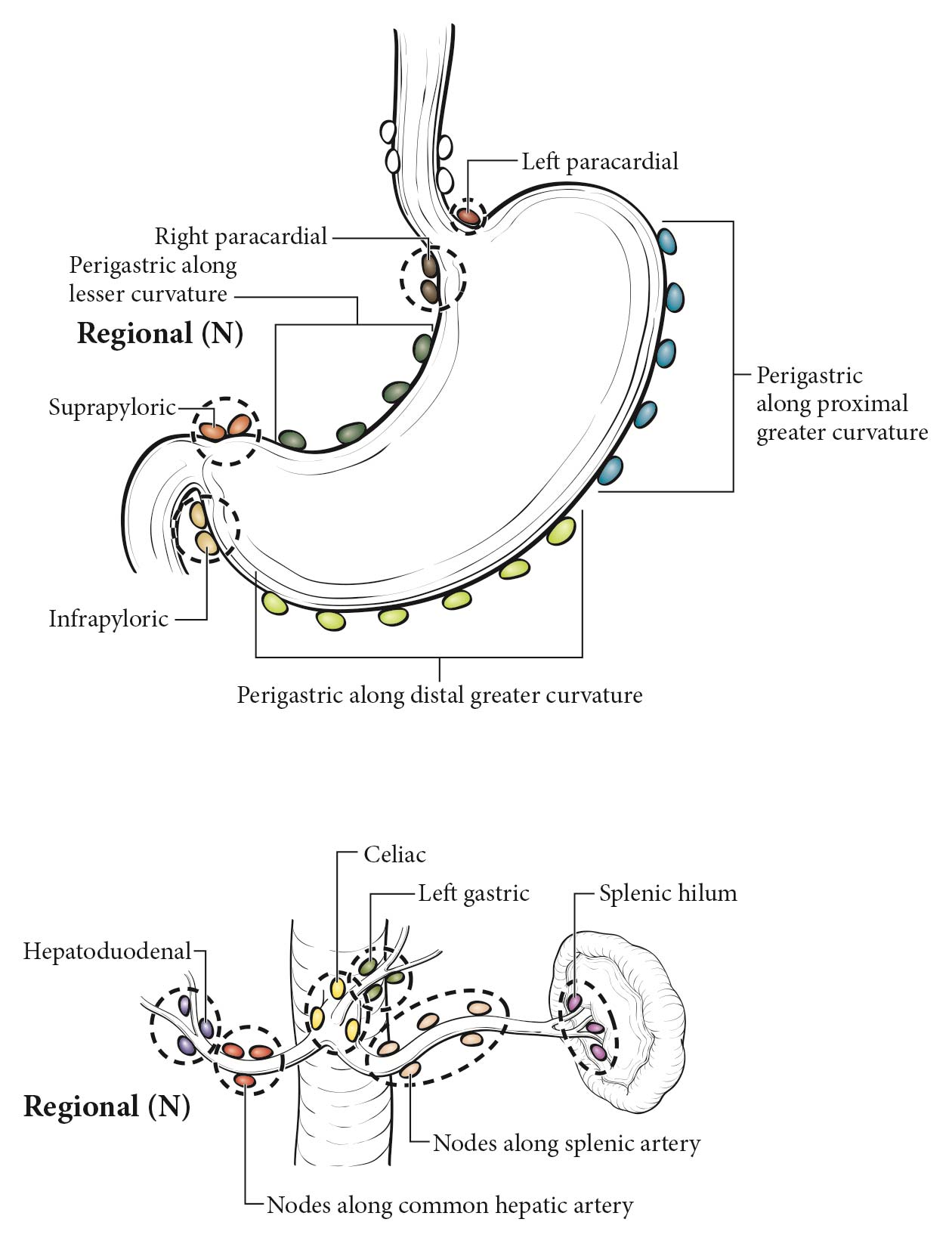

The lymphatic drainage areas routinely investigated are the lower periesophageal, right and left paracardial, lesser curve (gastrohepatic ligament), greater curve, and supra- and infrapyloric regions, and areas along major vessels, including the celiac axis, splenic and hepatic artery, porta hepatis, and splenic hilum. Opinions vary regarding the specific cutoff for what is considered malignant. The presence of hypoechoic, rounded, sharply demarcated structures greater than 10 mm on EUS may be considered diagnostic of malignant nodes.12 Histologic confirmation of nodal disease by EUS-guided FNA is strongly encouraged if it can be achieved without traversing an area of tumor.13 Although not necessary for the current prognostic staging, the number of nodes remains important for future prognostic efforts; therefore, we encourage careful counting and reporting of suspicious nodes along with interpretation of clinical T category.

Parts of the liver are seen readily with EUS with the scope positioned in the antrum and along the lesser curvature and cardia, allowing identification of liver metastases (M1), which may be confirmed by EUS-FNA.14 Similarly, the presence of ascites adjacent to the stomach raises suspicion for peritoneal metastases, if other causes of ascites are ruled out. However, this finding has not been shown to be a reliable indicator of M1 disease.15,16

Imaging

Primary Tumor (cT)

EUS may be ideal for cT categorization of the primary tumor. With advances in multidetector CT scanners and greater attention to improving gastric distention, together with the use of negative oral contrast, dynamic intravenous contrast enhancement, and multiplanar reformatting of images, the accuracy of cT category has improved.17-19 In this regard, CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with intravenous and oral contrast is used to describe cT in terms of location and degree of local invasion. However, overall, CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis still has a limited role in the cT category, especially for cT1, cT2, and cT3 tumors, although limitations also exist in identifying invasion of adjacent structures (cT4) unless gross invasion is present.20,21 FDG PET/CT generally is not useful in cT categorization because of the normal increased background uptake of FDG in the gastric mucosa together with the general lack of FDG uptake by signet ring cells and /or poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas.22-24 Although MR imaging has better contrast resolution than CT and has been reported in small studies to be comparable to CT, overall the imaging evaluation of cT categorization is limited.

Regional Lymph Nodes (cN)

CT of the chest and abdomen with intravenous and oral contrast and FDG PET/CT imaging are used to describe locoregional (cN) lymph nodes. In clinical practice, locoregional nodes generally are suspicious for tumor involvement if round and /or greater than 10 mm in short axis diameter. The portocaval lymph node, however, is an exception to these criteria. This lymph node has an elongated shape with a long transverse diameter and small anterior posterior diameter, and relying on measurement alone for this node results in frequent false positive interpretations. CT and FDG PET/CT are not optimal in detecting locoregional nodal metastasis.25-30 Additionally, the diagnostic benefit of FDG PET/CT is especially limited in patients with an early T classification (pT1) because of the low prevalence of nodal and distant metastases and the high rate of false positive PET findings.31,32 Because the criteria for cN classification have not been rigorously defined in peer-reviewed literature, the current cN classification requires evaluation of the size, shape, and number of abnormal lymph nodes in determining the cN classification. The diagnostic benefit of FDG PET/CT in detecting nodal metastasis is of limited value because of the high rate of false negative PET findings due to its inability to detect microscopic disease and because of poor FDG uptake by signet ring cells and /or poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas.

Metastatic Disease (cM)

CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with intravenous and oral contrast can detect distant metastasis (cM1). Because advanced gastric adenocarcinoma has a propensity to metastasize to the peritoneum, ovaries, and rectovesical pouch, pelvic CT imaging is useful in cM categorization. MR imaging is used less frequently as a primary imaging modality. The addition of FDG PET/CT imaging to conventional clinical staging improves the detection of metastases missed or not visualized on CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis.

Diagnostic Laparoscopy and Peritoneal Washing Evaluations

Diagnostic peritoneal staging laparoscopy is used to identify occult metastates not detected by imaging (or by EUS) and is recommended for all patients with tumor depth cT3 or greater, or in the presence of clinically suspicious nodes in the absence of distant metastases on imaging (CT or PET). It generally is performed as a separate surgical procedure and allows detection of gross metastases on the peritoneal surface and visceral organs as well as of microscopic malignant cells in the washings. Clinical studies have found positive peritoneal cytology to be an independent prognosticator,33,34 and this finding is considered pM1 for both the clinical and pathological classification M categories, resulting in clinical Stage IV and pathological Stage IV.

Peritoneal washing generally involves instilling ~200 mL of normal saline into the different quadrants of the abdominal cavity. The fluid is dispersed by gentle stirring of the area and then is aspirated from different portions of the body. Areas typically include the right and left subphrenic space and the pouch of Douglas. Ideally, greater than 50 mL of washings should be retrieved for cytologic assessment.

Residual Disease (R Classification)

Assessment of the R classification applies only to a surgically resected specimen. In addition to proximal and distal margins of resection, the status of the radial or circumferential margin of resection determines whether the tumor was excised completely. The R classification is based on a combination of intraoperative assessment by the surgeon and pathological evaluation of the resected specimen. R0 indicates no evidence of residual tumor. R1 indicates the presence of microscopic tumor at the margins, as defined by the College of American Pathologists (CAP); however, the Royal College of Pathologists (RCP) definition of R1 includes tumors within a 1-mm margin. Macroscopically visible tumor at margins is classified as R2. The presence of tumor cells at the inked radial margin constitutes a positive margin according to CAP criteria.

Early malignant lesions removed endoscopically by either an endoscopic submucosal dissection or an endoscopic mucosal resection should be assessed for pT designation along with the assessment of deep and lateral margins. The pathological assessment also should include the presence/absence of lymphovascular and /or perineural invasion, maximum tumor diameter, and the final histologic grade (including the presence of high-grade dysplasia). This information may assist in making future therapeutic decisions, including surveillance strategies.

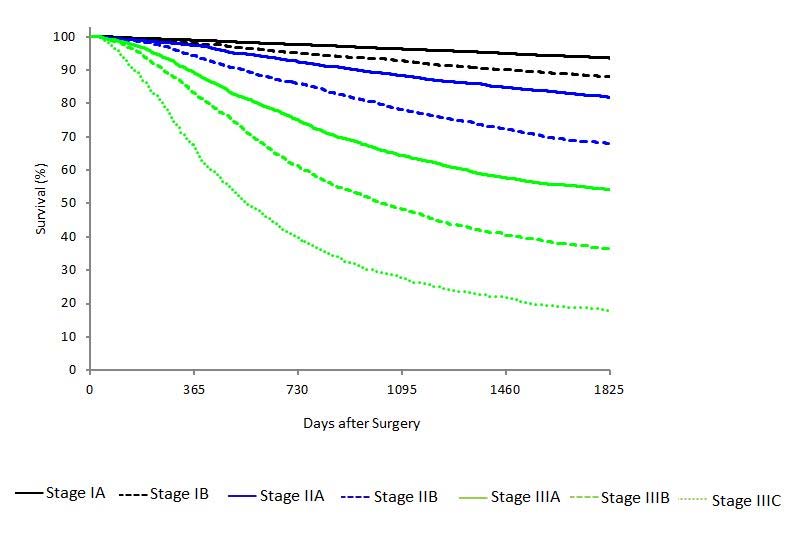

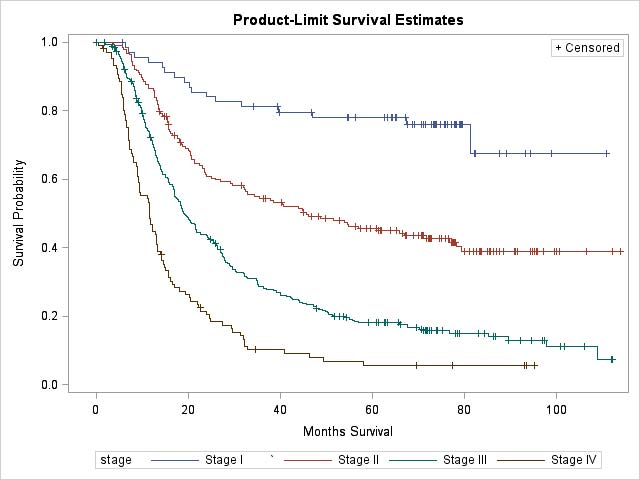

Pathological Classification

Pathological staging depends on data acquired clinically, together with findings from subsequent surgical exploration and examination of resected tissue (specimen). Surgical resections that qualify for pathological staging include total, near-total, subtotal, partial, proximal, and distal gastrectomy and antrectomy.

Primary Tumor (pT)

Depth of tumor invasion should be based on examination of the surgical specimen after resection. Tumor distance from closest margin or involvement of margin should be documented. Histologic classification, as well as grade and presence of lymphovascular or perineural invasion, should be documented according to CAP guidelines. The specimen should be tested for the presence of Helicobacter pylori infection.

Regional Lymph Nodes (pN)

Pathological assessment of regional lymph nodes entails the removal and histologic examination of nodes to evaluate the total number removed, as well as how many contain tumor. The number of nodes, as well as the number of positive nodes, should be documented.

Metastatic tumor deposits in the subserosal fat adjacent to a gastric carcinoma, without evidence of residual lymph node tissue, are considered regional lymph node metastases for purposes of gastric cancer staging. Tumor deposits are defined as discrete tumor nodules within the lymph drainage area of the primary carcinoma without identifiable lymph node tissue or identifiable vascular or neural structure. Shape, contour, and size of the deposit are not considered in these designations.

Metastatic Disease (pM)

Pathologically confirmed metastatic tissue obtained from a site outside of what is considered local or regional for gastric cancer is considered pM1. This designation includes tumor identified in distant nodal stations in the surgical resection specimen and tissue samples obtained from other organs (including peritoneum) showing malignant cells in peritoneal washings or implants.

When recording pathological stage, clinical stage M category (cM) may be used for final pathological Stage IV, such as pTpNcM0-1.